Georges Clemenceau facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Georges Clemenceau

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Nadar, 1904

|

|

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 16 November 1917 – 20 January 1920 |

|

| President | Raymond Poincaré |

| Preceded by | Paul Painlevé |

| Succeeded by | Alexandre Millerand |

| In office 25 October 1906 – 24 July 1909 |

|

| President | Armand Fallières |

| Preceded by | Ferdinand Sarrien |

| Succeeded by | Aristide Briand |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 16 November 1917 – 20 January 1920 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Paul Painlevé |

| Succeeded by | André Joseph Lefèvre |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 14 March 1906 – 24 July 1909 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Fernand Dubief |

| Succeeded by | Aristide Briand |

| President of the Council of Paris | |

| In office 28 November 1875 – 24 April 1876 |

|

| Preceded by | Pierre Marmottan |

| Succeeded by | Barthélemy Forest |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Georges Benjamin Clémenceau

28 September 1841 Mouilleron-en-Pareds, France |

| Died | 24 November 1929 (aged 88) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Mouchamps, Vendée |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Mary Eliza Plummer

(m. 1869; div. 1891) |

| Children | Michel Clemenceau |

| Alma mater | University of Nantes |

| Profession | Physician, journalist, statesman |

| Nicknames |

|

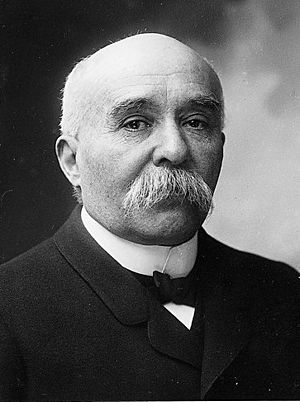

Georges Clemenceau (born 28 September 1841 – died 24 November 1929) was a very important French leader. He served as the Prime Minister of France twice. His first time was from 1906 to 1909, and his second was from 1917 to 1920.

Clemenceau was a key figure in French politics. He strongly believed in keeping the government and religion separate. He also supported giving a fresh start to people who were sent away for their part in the Paris Commune. He was against colonization (when one country takes control of another).

Originally a doctor, Clemenceau became a journalist. He played a huge role in the Third Republic of France. He is most famous for successfully leading France through the end of World War I. After about 1.4 million French soldiers died, he demanded a complete victory over Germany. He wanted Germany to pay for damages, give back colonies, and be stopped from rearming. He also wanted Alsace–Lorraine, a region taken by Germany in 1871, to be returned to France.

He achieved these goals through the Treaty of Versailles, signed after the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. People called him Père la Victoire ("Father of Victory") or Le Tigre ("The Tiger"). He kept a tough stance against Germany even in the 1920s. He tried to get defense agreements with the United Kingdom and the United States to protect against future German attacks. However, these agreements never happened because the US Senate did not approve the treaty.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Georges Clemenceau was born in Mouilleron-en-Pareds, a rural area in Vendée, France. His family had many doctors, but his father, Benjamin Clemenceau, managed his lands and investments instead of practicing medicine. Benjamin was very active in politics and was even arrested a few times. He taught his son to love learning and to believe in radical politics.

Georges's mother was a Protestant, but his father was an atheist and did not want his children to have religious education. Clemenceau himself was an atheist throughout his life. He became a leader of groups that wanted to separate the church and the government in France.

After finishing school in Nantes, Clemenceau moved to Paris in 1858 to study medicine. He became a doctor in 1865.

Early Political Steps

In Paris, young Clemenceau became very involved in politics and writing. In 1861, he helped start a weekly newspaper called Le Travail. He was even arrested and spent 77 days in prison in 1862 for putting up posters for a protest. This experience made him dislike the government of Napoleon III even more.

After becoming a doctor, Clemenceau wrote many articles criticizing the government. He left France for the United States in 1865 because the government was cracking down on people who disagreed with them.

He lived in New York City from 1865 to 1869, after the American Civil War. He worked as a doctor but spent most of his time writing political articles for a Parisian newspaper. He also taught French and horseback riding at a girls' school in Stamford, Connecticut, where he met his future wife. During this time, he joined French groups in New York that were against the French government.

His time in America made him believe strongly in American democracy. He also learned about political compromise, which became a key part of his later career.

Family Life

On 23 June 1869, Georges Clemenceau married Mary Eliza Plummer in New York City. She was one of his students at the school where he taught.

After they married, the Clemenceaus moved to France. They had three children: Madeleine (born 1870), Thérèse (1872), and Michel (1873). Their marriage ended in divorce in 1891. Clemenceau gained custody of their children.

Starting the Third Republic

Clemenceau returned to Paris in 1870 after France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. He became a doctor again in Vendée. He was then made mayor of the 18th district of Paris, which included Montmartre. He was also elected to the French National Assembly.

When the Paris Commune took power in March 1871, Clemenceau tried to find a peaceful solution between the Commune's leaders and the French government. He was not successful. The Commune said he was not the legal mayor. He ran for election to the Commune council but did not get enough votes. He was not in Paris when the French Army stopped the Commune in May 1871.

After the Commune fell, he was elected to the Paris city council in July 1871. He stayed on the council until 1876 and became its president in 1875.

In the Chamber of Deputies

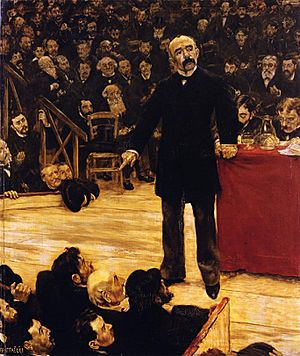

In 1876, Clemenceau was elected to the Chamber of Deputies. He quickly became a leader of the radical group because of his energy and sharp speaking skills. He strongly opposed the government's anti-republican policies. In 1879, he became well-known for demanding that the government leaders be investigated.

From 1876 to 1880, Clemenceau was a main supporter of giving a general pardon to thousands of Communards. These were members of the 1871 Paris Commune who had been sent away to New Caledonia. With other radical politicians and figures like the poet Victor Hugo, he helped pass a general pardon on 11 July 1880. This allowed the Communards to return to France.

In 1880, Clemenceau started his own newspaper, La Justice. It became a main voice for radical ideas in Paris. During this time, he was known for criticizing and bringing down governments, but he avoided taking office himself. He strongly opposed France's colonial policy. He believed it was wrong and distracted from the more important goal of getting back Alsace and Lorraine from Germany. In 1885, his criticism helped bring down the government after the Sino-French War.

In the 1885 elections, he won seats in both Paris and the Var region. He chose to represent Var. He helped keep Prime Minister Charles de Freycinet in power in 1886. He also helped include Georges Ernest Boulanger as war minister. But when Boulanger became too ambitious, Clemenceau stopped supporting him.

Clemenceau also played a big part in the resignation of President Jules Grévy in 1887. He refused to form a government himself and helped elect an "outsider," Marie François Sadi Carnot, as president.

His political group weakened after disagreements over Boulanger. Also, his connection to a businessman involved in the Panama affair caused him trouble. He even fought a duel with a politician named Paul Déroulède in 1892, but no one was hurt.

Clemenceau remained a leading voice for French radicalism. However, his opposition to the Franco-Russian Alliance made him unpopular. In the 1893 elections, he lost his seat in the Chamber of Deputies, which he had held since 1876.

The Dreyfus Affair

After his defeat in 1893, Clemenceau focused on journalism for almost ten years. His career was also affected by the long-running Dreyfus case. He strongly supported Émile Zola and opposed the anti-Jewish campaigns. During the affair, Clemenceau wrote 665 articles defending Dreyfus.

On 13 January 1898, Clemenceau published Émile Zola's famous letter, J'Accuse...!, on the front page of his newspaper, L'Aurore. This controversial article was an open letter to Félix Faure, the president of France.

In 1900, he left La Justice to start a weekly magazine called Le Bloc, where he wrote almost everything himself. In 1902, he was elected as a senator for the Var region. He had previously wanted to get rid of the French Senate, as he saw it as too traditional. He served as senator until 1920.

Clemenceau joined the Independent Radicals in the Senate and became more moderate. He still strongly supported the government of Prime Minister Émile Combes, who led the effort to separate church and state. In 1903, he took charge of L'Aurore again. Through this newspaper, he pushed for the Dreyfus affair to be re-examined and for the separation of church and state in France. This separation became law in 1905.

Becoming Prime Minister

In March 1906, the government fell apart because of protests over the new law separating church and state. Clemenceau was appointed Minister of the Interior in the new government. He reformed the French police and ordered strong actions against workers' protests. He helped create scientific police methods and founded the "mobile squads," which were nicknamed Brigades du Tigre ("The Tiger's Brigades") after Clemenceau himself.

A miners' strike in 1906, after a terrible mine accident, threatened to cause widespread chaos. Clemenceau sent the military against the strikers. He also stopped a wine growers' strike. His actions angered the socialist party. When the government resigned in October, Clemenceau became Prime Minister.

During 1907 and 1908, he worked to improve relations with Britain, creating the Entente cordiale. This gave France an important role in European politics. Problems with Germany and criticism from the Socialist party over the First Moroccan Crisis were resolved at the Algeciras Conference.

Clemenceau was defeated in a debate about the navy in July 1909. He resigned and was replaced by Aristide Briand.

Between 1909 and 1912, Clemenceau traveled and gave speeches. He visited South America in 1910. In 1913, he started a new newspaper in Paris, L'Homme libre ("The Free Man"), where he wrote a daily article. In his writings, he focused more on foreign policy and criticized the socialists' anti-war views.

World War I Leadership

When World War I began in August 1914, Clemenceau's newspaper was one of the first to be censored by the government. He changed its name to L'Homme enchaîné ("The Chained Man") and criticized the government for not being open or effective. He still supported the patriotic unity against Germany.

Even with censorship, Clemenceau had a lot of political power. He was a strong critic of the French government during the war. He believed they were not doing enough to win. His main goal was to get back Alsace-Lorraine. In late 1917, with Italy losing battles and Russia leaving the war, Clemenceau argued that France should not make a separate peace with Germany. He believed that Germany had no real intention of giving back Alsace-Lorraine. His strong opposition made him the most well-known critic.

Second Term as Prime Minister

In November 1917, during a very difficult time for France in World War I, Clemenceau became Prime Minister. He encouraged everyone to work together and avoid disagreements among politicians.

Leading France to Victory

Clemenceau worked from the Ministry of War. One of his first actions was to remove General Maurice Sarrail from his command.

When Clemenceau became Prime Minister in 1917, victory seemed far away. There was little fighting on the western front as they waited for American support. Italy was struggling, and Russia had almost stopped fighting. At home, there were protests against the war, a lack of resources, and air raids on Paris. Many politicians secretly wanted peace. It was a huge challenge for Clemenceau.

At first, the soldiers in the trenches saw him as "just another politician." But slowly, his confidence began to inspire them. He often visited the trenches, which encouraged the troops. This confidence spread to the home front. People started to say, "We believed in Clemenceau." He worked well with military leaders, which was key to the final victory.

The media also welcomed Clemenceau. They felt France needed strong leadership. Everyone knew he was never discouraged and always believed France could win.

Tough Decisions in 1918

As the war got worse in early 1918, Clemenceau continued to push for total war. He promised victory with justice, loyalty to soldiers, and harsh punishment for crimes against France.

Joseph Caillaux, a former Prime Minister, wanted to surrender to Germany. Clemenceau saw him as a threat to national security. Unlike past leaders, Clemenceau publicly moved against Caillaux. Caillaux was arrested and imprisoned. Clemenceau believed Caillaux's crime was not believing in victory.

The arrests raised questions about Clemenceau's strictness. But he argued that he only took powers needed to win the war. These trials made the public feel confident that the government was taking strong action. Clemenceau also allowed more freedom for newspapers to criticize politicians.

In 1918, Clemenceau thought France should adopt Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, especially the one calling for Alsace-Lorraine to return to France. This meant victory would achieve France's main war goal.

As war minister, Clemenceau worked closely with his generals. He also visited the poilus, the French infantrymen, in the trenches. He spoke to them and assured them the government cared. The soldiers respected Clemenceau's bravery, as he often visited them very close to the German front lines. These visits earned him the title "Père la Victoire" (Father of Victory).

German Spring Offensive and Allied Counter-Offensive

On 21 March 1918, the Germans launched a huge attack. The Allies were surprised, and a gap opened in their lines, threatening Paris. This defeat made Clemenceau and the Allies realize they needed a single, unified command. Ferdinand Foch was appointed as the overall commander.

The German advance continued, and Clemenceau thought Paris might fall. Some people believed that if Clemenceau, Foch, and Philippe Pétain stayed in power, France would be lost. They thought a new government would make peace with Germany. Clemenceau strongly opposed these ideas. He gave an inspiring speech in the Chamber of Deputies, and they voted to support him.

As the Allies pushed the Germans back, it became clear Germany could not win. On 11 November 1918, an armistice (agreement to stop fighting) was signed with Germany. Clemenceau was celebrated in the streets. The French public saw him as a strong, energetic leader who was key to the Allied victory.

Paris Peace Conference

After World War I, a peace conference was held in Paris. The famous Treaty of Versailles was signed there. On 13 December 1918, US President Woodrow Wilson was warmly welcomed in France. His Fourteen Points and idea of a League of Nations had a big impact on the French people, who were tired of war. Clemenceau quickly saw that Wilson was a man of strong beliefs.

Since the conference was in France, Clemenceau was chosen to be its president. He spoke both English and French, the official languages of the conference. Clemenceau had full control of the French team. He kept military leaders and even the French president, Raymond Poincaré, out of the negotiations. He also excluded members of parliament, saying he would negotiate the treaty, and parliament would simply vote on it.

The conference was much slower than expected. Clemenceau became frustrated and told an American journalist that Germany had won the war economically. He believed Germany's factories were untouched, and its economy would soon be stronger than France's.

Clemenceau's distrust of Wilson and David Lloyd George (Britain's leader) and his dislike for President Poincaré often made negotiations difficult. When talks stalled, Clemenceau sometimes shouted and left the room.

Rhineland and the Saar Region

A major issue was the German Rhineland region. Clemenceau believed that if Germany controlled this area, France would be open to invasion. He wanted the Rhine River to be Germany's border, with the land between the Rhine and France becoming an independent state.

Finally, Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson promised immediate military help if Germany attacked France. They also agreed that the Allies would occupy the Rhineland for fifteen years, and Germany could never put soldiers there. Clemenceau added a rule (Article 429) that allowed Allied occupation beyond fifteen years if France's safety was not guaranteed. This was in case the US Senate did not approve the treaty, which would also cancel Britain's promise. This is exactly what happened.

President Poincaré and Marshal Ferdinand Foch wanted an independent Rhineland state. Foch thought the Treaty of Versailles was too easy on Germany, saying, "This is not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years." But Clemenceau believed an alliance with America and Britain was more valuable than France holding onto the Rhineland alone.

Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Wilson started meeting in a smaller group called the Council of Four to make decisions faster. They also discussed the future of the German Saar region. Clemenceau felt France deserved the Saar and its coal mines because Germany had damaged French mines. Wilson disagreed, so Lloyd George suggested a compromise: France got the coal mines, and the Saar region would be under French control for 15 years. After that, people in the Saar would vote on whether to rejoin Germany.

Clemenceau also supported the smaller ethnic groups of the old Austrian-Hungarian empire. He wanted to weaken Hungary, just like Germany, to prevent a large power in Central Europe. He saw the new country of Czechoslovakia as a way to stop Communism.

War Reparations

Clemenceau was not an expert in money matters. He was under great pressure from the public and parliament to make Germany pay as much as possible for the war. Everyone agreed Germany should not pay more than it could afford, but estimates varied widely. Clemenceau decided to create a special commission to figure out how much Germany could pay. This meant the French government was not directly responsible for setting the exact amount.

Defending the Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. Clemenceau then had to defend it against critics who thought the compromises he made were not enough for France. He admitted the treaty was not perfect but said it was the best they could get since many countries fought together.

The French Parliament approved the treaty by a large vote. On 11 October, Clemenceau gave his last speech in parliament. He said that trying to divide Germany would not work and that France must learn to live with sixty million Germans. He also said that France needed to have more children to remain strong.

Domestic Policies

During Clemenceau's final time as Prime Minister, several laws were passed to control working hours. A law in April 1919 set an eight-hour day for most workers. In June, this was extended to all mining workers. In August 1919, a similar limit was set for workers on French ships. Another law in 1919 stopped bakeries from working between 10 P.M. and 4 A.M. These changes aimed to improve working conditions.

Presidential Bid and Retirement

In 1919, France changed its election system. A group of right-wing parties won a majority. Clemenceau's friend, Georges Mandel, urged him to run for president. Clemenceau agreed to serve if elected, but he did not want to campaign. He wanted to be chosen by popular demand as a national hero. However, a preliminary meeting of politicians chose Paul Deschanel over Clemenceau. Because he did not get strong support, Clemenceau refused to run in the final vote.

He resigned as Prime Minister on 17 January 1920 and left politics. He later criticized France's solo occupation of the German city of Frankfurt in 1920.

He traveled to Egypt and the Far East. In 1921, he visited England and received an honorary degree from University of Oxford. He met David Lloyd George again.

In late 1922, Clemenceau gave lectures in the United States. He defended France's policies, including war debts and reparations, and criticized America's decision to stay out of European affairs. He was well-received but America's policy did not change. In 1926, he wrote an open letter to President Calvin Coolidge arguing against France paying all its war debts.

He wrote two short biographies and a large two-volume book about philosophy, history, and science. He also wrote his memoirs, Grandeur and Misery of Victory, which were published after his death. He criticized Marshal Foch and his successors for weakening the Versailles Treaty.

Georges Clemenceau died on 24 November 1929 and was buried in Mouchamps.

Personal Interests

Clemenceau was a long-time friend and supporter of the famous impressionist painter Claude Monet. He helped persuade Monet to have eye surgery in 1923. For over ten years, Clemenceau encouraged Monet to finish his gift to the French state: the large Les Nymphéas paintings. These are now displayed in specially built oval galleries at the Paris Musée de l'Orangerie, which opened in 1927.

Clemenceau had fought many duels against political opponents. He knew the importance of exercise and practiced fencing every morning, even when he was old.

He was very interested in Japanese art, especially Japanese ceramics. He collected about 3,000 small incense containers (kōgō), which are now in museums.

Places Named After Clemenceau

- The Musée Clemenceau in Paris was once his apartment, bought for him by a friend.

- Clemenceau, Arizona, USA, was named in his honor in 1917.

- Mount Clemenceau (3,658m) in the Canadian Rockies was named after him in 1919.

- A French battleship and the aircraft carrier Clemenceau were named after him.

- Champs-Élysées – Clemenceau is a Paris Metro station.

- The Cuban Romeo y Julieta cigar brand once had a size named Clemenceau.

- Streets in Beirut, Montreal, Belgrade, Bucharest, Antibes, and Singapore are named after him.

- His famous quote, "War is too important to be left to the generals," was used in the 1964 film Dr. Strangelove.

Screen Portrayals

Clemenceau has been played by several actors in films and TV shows, including:

- Leonard Shephard in Dreyfus (1931)

- Grant Mitchell in The Life of Emile Zola (1937)

- Marcel Dalio in Wilson (1944)

- John Bennett in Fall of Eagles (1974)

- Brian Cox in The Nature Vacations of Fantastic World of the Adventure (2016)

- Gérard Chaillou in An Officer and a Spy (2019)

- André Dussolier in The Tiger and the president (2022)

Images for kids

-

Clemenceau by Cecilia Beaux (1920)

-

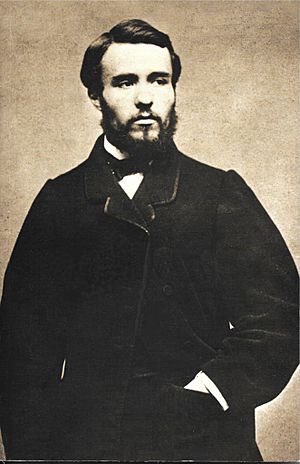

Clemenceau portrait by Nadar

See also

In Spanish: Georges Clemenceau para niños

In Spanish: Georges Clemenceau para niños

- Interwar France

- International relations (1919–1939)

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |