French colonial empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

French Colonial Empire

Empire Colonial Français

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1534–1980 | |||||||||||

|

Left: Royal Standard of France (before 1792)

Right: Flag of the French Empire and the French Republic |

|||||||||||

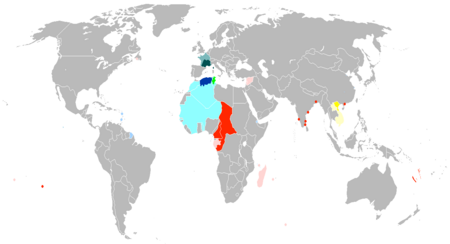

The First (light blue) and Second (dark blue) French colonial empires

|

|||||||||||

| Status | Colonial empire | ||||||||||

| Capital | Paris | ||||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism, Islam, Judaism, Louisiana Voodoo, Haitian Vodou, Buddhism, Hinduism | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 1534 | |||||||||||

| 1803 | |||||||||||

|

• Conquest of Algeria

|

1830–1903 | ||||||||||

|

• French Union

|

1946 | ||||||||||

| 1958 | |||||||||||

|

• Independence of Vanuatu

|

1980 | ||||||||||

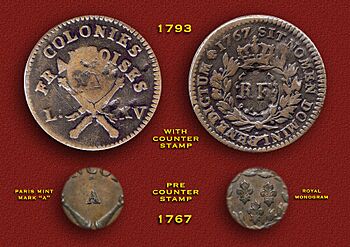

| Currency | French franc and various other currencies | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | FR | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

The French colonial empire was made up of lands overseas that France controlled from the 16th century onwards. These lands were called colonies, protectorates (where France protected and influenced local rulers), and mandate territories (lands managed by France after wars).

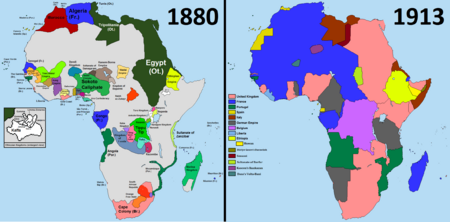

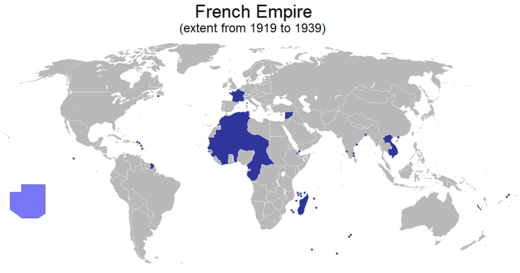

Historians usually talk about two main parts of this empire. The "First French colonial empire" existed until 1814. Most of its lands were either lost or sold by then. The "Second French colonial empire" began in 1830 when France took over Algeria. Before World War I, France's colonial empire was the second largest in the world, after the British Empire.

France started setting up colonies in the Americas, the Caribbean, and India in the 1500s. But it lost most of these after the Seven Years' War. Its North American lands went to Britain and Spain. However, Spain later gave Louisiana back to France in 1800. France then sold Louisiana to the United States in 1803.

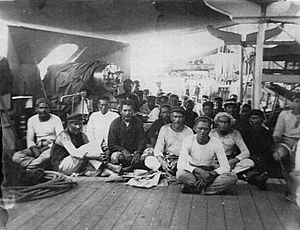

France built a new empire mostly after 1850. This new empire focused mainly on Africa, Indochina, and the South Pacific. The colonies provided raw materials to France and bought French manufactured goods. After the Franco-Prussian War, which made Germany very powerful, France saw building an empire as a way to regain its importance in the world. It also helped provide soldiers during the world wars.

A main reason France gave for having colonies was the "Civilizing Mission" (Mission civilisatrice). This idea suggested that it was France's duty to bring its culture and way of life to other peoples. In 1884, Jules Ferry, a supporter of colonialism, said that "higher races" had a "duty to civilize the inferior races." France offered full citizenship rights to people in its colonies. However, in reality, people in the colonies were often treated as subjects, not as equal citizens. France sent only a few settlers to its empire, except for Algeria. In Algeria, French settlers, called Pieds-Noirs, became powerful even though they were a minority.

During World War II, Charles de Gaulle and the Free French forces gradually took control of the overseas colonies. They used these colonies as a base to prepare for the liberation of France. After 1945, movements against colonial rule started to grow. Rebellions in Indochina and Algeria were very costly for France, and it lost both colonies. After these conflicts, many other colonies gained independence peacefully after 1960. The French Constitution of 27 October 1946 created the French Union, which lasted until 1958. Remaining parts of the colonial empire became overseas departments and territories within France. Today, these areas cover about 119,394 square kilometers and had 2.8 million people in 2021. France still has connections with its former colonies through groups like La Francophonie and shared currency like the CFA franc.

Contents

- First French Colonial Empire (16th Century to 1814)

- Second French Colonial Empire (After 1830)

- Decolonization

- Demographics

- Territories

- Images for kids

- See also

First French Colonial Empire (16th Century to 1814)

French Colonies in the Americas

French colonization in the Americas started in the 16th century. Explorers like Giovanni da Verrazzano and Jacques Cartier made early trips. French fishermen also often visited the Grand Banks near Newfoundland. However, Spain wanted to keep its control over the Americas. Also, religious wars in France in the late 1500s stopped France from focusing on building colonies. Early French attempts to set up colonies in Brazil (like "France Antarctique" in 1555) and Florida (like Fort Caroline in 1562) failed. This was because France wasn't very interested, and Portugal and Spain were watchful.

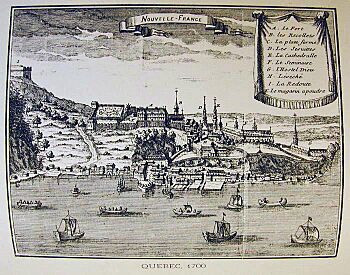

The real start of France's colonial empire was on July 27, 1605. This is when Port Royal was founded in Acadia (now Nova Scotia, Canada). A few years later, in 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec. Quebec became the main city of the huge, but not very populated, fur-trading colony of New France (also called Canada).

New France had a small population because it focused more on fur trading than on farming settlements. Because of this, the French worked closely with local First Nations communities. The French built strong military, trade, and diplomatic ties with these groups. These alliances became very long-lasting. However, religious groups in France wanted to convert the First Nations people to Catholicism.

By making alliances with different Native American tribes, the French gained some control over much of North America. French settlements were mostly along the St. Lawrence River Valley. At first, New France was developed as a trading colony. After Jean Talon arrived in 1665, France started to help its American colonies grow their populations, similar to the British colonies. However, Acadia was lost to the British in the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. In France, there was not much interest in colonies. The main focus was on power in Europe. For most of its history, New France was far behind the British North American colonies in both population and economy.

In 1699, French land claims in North America grew even more. This happened with the founding of Louisiana in the Mississippi River basin. A large trading network connected Louisiana to Canada through the Great Lakes. This network was protected by many forts, especially in the Illinois Country and what is now Arkansas.

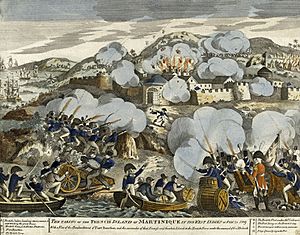

As the French empire in North America grew, France also started building a smaller but more profitable empire in the West Indies. Settlements along the South American coast, in what is now French Guiana, began in 1624. A colony was founded on Saint Kitts in 1625. This island was shared with the English until 1713, when it was fully given to France. The island of Commonwealth of Dominica also saw more French settlers from the 1630s. The Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique founded colonies in Guadeloupe and Martinique in 1635. A colony was later founded on Saint Lucia by 1650.

These colonies had large farms that produced food. These farms were built and kept running using slavery. The supply of people forced into slavery came from the African slave trade. Local resistance from indigenous peoples led to the Carib Expulsion in 1660. France's most important Caribbean colony was set up in 1664. This was Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), on the western part of the Spanish island of Hispaniola. In the 1700s, Saint-Domingue became the richest sugar colony in the Caribbean. The eastern part of Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic) was also under French rule for a short time after Spain gave it to France in 1795.

French Colonies in Asia

After the French Wars of Religion ended in 1598, King Henry IV encouraged trade with Africa and Asia. In December 1600, a company was formed to trade with the Moluccas and Japan. Two ships sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in May 1601. One ship was wrecked, but the other reached Ceylon and traded in Sumatra. This ship was later captured by the Dutch.

From 1604 to 1609, Henry IV became very interested in Asian trade. He tried to create a French East India Company, like those in England and the Netherlands. On June 1, 1604, he gave special rights to merchants from Dieppe to trade with Asia for 15 years. However, no ships were sent until 1616.

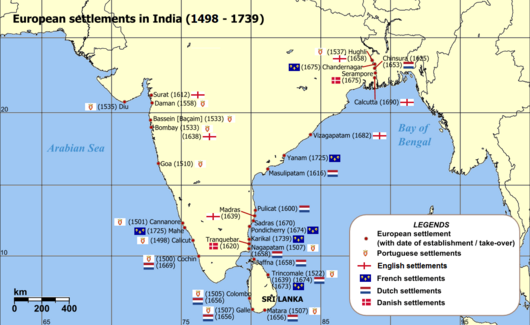

Colonies were set up in India at Chandernagore (1673) and Pondichéry (1674). Later, more were established at Yanam (1723), Mahe (1725), and Karikal (1739). These became known as French India. In 1664, the French East India Company was created to compete for trade in the East.

French Colonies in Africa

Even though France first focused on colonizing the Americas and Asia, it did set up some colonies and trading posts in Africa. Early French colonization in Africa began in what is now Senegal, Madagascar, and the Mascarene Islands. These early French projects, partly managed by the French East India Company, focused on large farms and forced labor. These farms grew one type of crop and used people forced into slavery. Poor living conditions, famines, and diseases made life very difficult for enslaved people in French colonies.

French presence in Senegal started in 1626. Formal colonies and trading posts were set up in 1659 with the founding of Saint-Louis, and in 1677 with Gorée. The first settlement in Madagascar began in 1642 with Fort Dauphin.

France's early colonial expansion in Senegal and Madagascar was mainly to get natural resources like gum arabic and peanuts. They also wanted to control the slave trade in the 17th and 19th centuries. By controlling seaports, the French aimed to force enslaved people to be sent abroad for profit.

Colonial development focused on producing goods for export, while local industries remained very undeveloped. There was a lot of production for export, especially peanuts in Senegal. In coastal areas, the French also set up farms that used enslaved labor. Early French development focused on building roads to connect natural resources to harbors and ports.

Other early French settlements were on the Mascarene Islands. These include Reunion Island, Mauritius, and Rodrigues. Reunion Island was first settled in 1642 and was managed by the French East India Company starting in 1665. After the Netherlands first settled Mauritius, France took control and renamed it the Island of France in 1721. France also took control of Rodrigues in 1735 and Seychelles in 1756.

On Reunion Island, the French East India Company brought in the slave trade in the 1730s. They also brought coffee and aimed to create a farming economy based on forced labor. Like other colonies with large farms, French colonists were a minority on Reunion Island. In 1763, there were only 4,000 French colonists, but over 18,000 enslaved Africans. Most enslaved people on Reunion Island worked on coffee farms. They mainly came from Madagascar, Mozambique, and Senegal.

The economy of Mauritius (Island of France) was also based on a system of forced labor on farms. These farms grew sugar cane, cotton, indigo, rice, and wheat. About 2,000 colonists and enslaved people from Reunion Island moved to Mauritius. Conditions for enslaved people on the Mascarene Island farms were very harsh. Forced labor led to many deaths due to poor living conditions and famines. After several crop failures from 1725 to 1737, about 10% of the enslaved populations on the islands died from famine and disease.

End of the First French Colonial Empire

Conflicts with Britain

In the mid-1700s, France and Britain started a series of colonial wars. These wars eventually destroyed most of the first French colonial empire and pushed France almost entirely out of the Americas. These conflicts included the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the American Revolution (1775–1783), the French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1802), and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). This long period of conflict is sometimes called the Second Hundred Years' War.

The War of the Austrian Succession did not have a clear winner. However, the Seven Years' War ended in a French defeat. The British, who had many more settlers (over one million compared to about 50,000 French settlers), took over New France. They also took most of France's Caribbean colonies and all its outposts in French India.

After the war, France got its Indian outposts and the Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe back. But Britain had won the competition for influence in India. North America was completely lost. Most of New France went to Britain. Louisiana was given to Spain by France as payment for Spain joining the war late. Britain also took Grenada and Saint Lucia in the West Indies. At the time, losing Canada did not cause much sadness in France. Many people thought colonialism was not important and was wrong.

The French colonial empire recovered a little during the French help in the American Revolution. Saint Lucia was returned to France by the Treaty of Paris in 1783. But this was not as much as France had hoped for.

Haitian Revolution

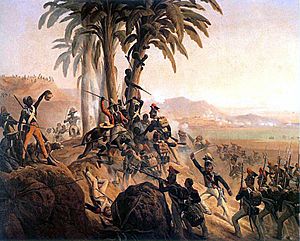

A big disaster for France's remaining empire happened in 1791. Saint Domingue (the western part of Hispaniola), France's richest and most important colony, was torn apart by a huge slave revolt. This revolt was partly caused by disagreements among the island's leaders, which came from the French Revolution of 1789.

The enslaved people, led first by Toussaint L'Ouverture and later by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, fought against French and British forces. The French sent an army in 1802, but it failed. The British navy also set up a strong blockade. As a result, the Empire of Haiti gained independence in 1804. It became the first black republic in the world. Many people died during this conflict. Of the 55,131 French soldiers sent to Haiti in 1802–03, 45,000 died, mostly from disease.

Meanwhile, France's war with Britain started again. The British quickly captured almost all remaining French colonies. These were returned in 1802, but when war restarted in 1803, the British took them back. France had gotten Louisiana back from Spain in 1800. But the success of the Haitian Revolution convinced Napoleon that holding Louisiana would not be worth the cost. So, he sold it to the United States in 1803.

Failed Invasion of Egypt

France tried to set up a colony in Egypt from 1798 to 1801, but it was not successful. Many soldiers died or were wounded on both sides during this campaign.

Second French Colonial Empire (After 1830)

After the Napoleonic Wars, Britain returned most of France's colonies. These included Guadeloupe and Martinique in the West Indies, French Guiana in South America, trading posts in Senegal, Réunion in the Indian Ocean, and France's small Indian lands. However, Britain kept Saint Lucia, Tobago, the Seychelles, and Mauritius.

In 1825, Charles X sent an expedition to Haïti. The second French colonial empire began in 1830 with the French invasion of Algeria. Algeria was fully conquered by 1903. Historian Ben Kiernan estimates that many Algerians died during this conquest by 1875.

French Colonies in Africa

Morocco

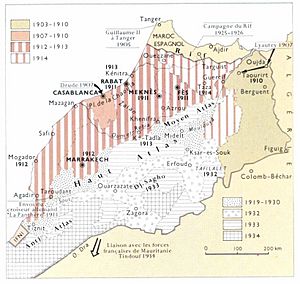

The French Colonial Empire set up a protectorate in Morocco from 1912 to 1956. France mostly used an indirect rule system. They kept the existing Moroccan government and Sultan in charge, but strongly influenced them.

French rule in Morocco was unfair to native Moroccans and hurt the Moroccan economy. Moroccans were treated as second-class citizens. For example, the French built many sewers in new areas for French settlers, but very few in Moroccan communities. Land was also much more expensive for Moroccans than for French settlers. Moroccans were not allowed to buy land from French settlers.

Morocco's economy was set up to help French businesses, not Moroccan workers. Morocco had to import all its goods from France, even if they cost more. Also, improvements in farming and irrigation only helped colonial farmers, leaving Moroccan farms behind.

Between 1914 and 1921, the Zaian Confederation of Berber Tribes, from the Atlas Mountains, fought against French rule. World War I stopped France from fully committing to the conflict, so French forces suffered many losses. For example, 600 French soldiers died at the Battle of El Herri in 1914. The fighting was mostly guerrilla warfare. The Zaian forces also received help from the Central Powers.

The Berber leader Abd el-Krim (1882–1963) organized armed resistance against Spain and France for control of Morocco. Spain had faced unrest since the 1890s. In 1921, Spanish forces were defeated at the Battle of Annual. El-Krim founded an independent Rif Republic that lasted until 1926, but no other countries recognized it. France and Spain worked together to defeat it. They sent 200,000 soldiers, forcing el-Krim to surrender in 1926. He was sent away to the Pacific until 1947. Morocco became calm, and in 1936, it became the place where Francisco Franco started his revolt against Spain.

Tunisia

The French protectorate of Tunisia lasted from 1881 to 1956. It began after France successfully invaded Tunisia in 1881. On April 24, 1881, France sent 35,000 troops from Algeria to invade several Tunisian cities.

Like in Morocco, the French ruled indirectly. They kept the existing government structure. The bey (ruler) remained an absolute monarch, and Tunisian ministers were still appointed. However, they were all under French authority. Over time, the French slowly weakened the local power structures and brought more power to the French colonial administration.

French West Africa

French West Africa was a group of eight French colonial territories. These included French Mauritania, French Senegal, French Guinea, French Ivory Coast, French Niger, French Upper Volta, French Dahomey, French Togoland, and French Sudan.

At the start of Napoleon III's rule, France's presence in Senegal was small. It included a trading post on Gorée island, a narrow coastal strip, the town of Saint-Louis, and a few trading posts inland. The economy had largely been based on the slave trade until France abolished slavery in its colonies in 1848. In 1854, Napoleon III appointed Louis Faidherbe, a French officer, to govern and expand the colony. Faidherbe built forts along the Senegal River, made alliances with local leaders, and sent expeditions against those who resisted French rule. He built a new port at Dakar, set up telegraph lines and roads, and later built a rail line between Dakar and Saint-Louis. He also built schools, bridges, and water systems. He introduced large-scale farming of peanuts as a commercial crop. Senegal became the main French base in West Africa and a model colony. Dakar became a very important city in the French Empire and in Africa.

French Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa was a group of French colonies in the Sahel and Congo River regions of Africa. These colonies included French Gabon, French Congo, Ubangui-Shari, and French Chad.

Cameroon

Cameroon was first colonized by the German Empire in 1884. The local people of Cameroon refused to work on German projects, which led to forced labor. After World War I, France and Britain divided the colony. The French colony lasted from 1916 until it gained self-rule in 1960.

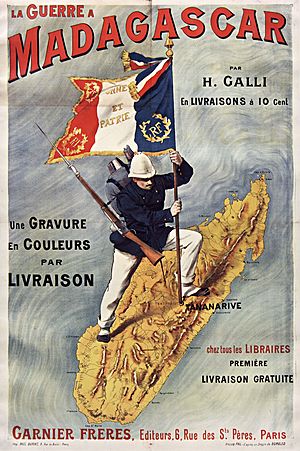

Madagascar

French rule in Madagascar began in 1896 when France took control by force. It ended in the 1960s when Madagascar gained self-rule. Under French control, the colony of Madagascar included other areas like Comoros, Mayotte, Réunion, and several smaller islands.

Algeria

The French conquest of Algeria started in 1830 with the invasion of Algiers. It was mostly finished by 1852, but not fully complete until 1903. French colonization of Algeria involved military conquest and overthrowing the existing government. French rule lasted until Algerian independence in 1962. French colonization in Algeria caused much suffering for the local Algerians. It also broke up the Algerian government and created unfair systems that discriminated against the local population.

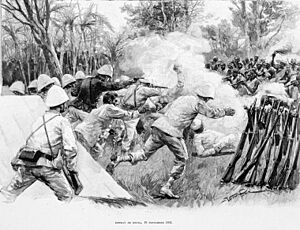

The French military invasion of Algeria began in 1830 with a naval blockade. Then, 37,000 French soldiers landed in Algeria. The French captured the port of Algiers in 1830, removing Hussein Dey, the ruler. They also took other coastal towns. About 100,000 French soldiers were sent to conquer Algeria. Algerian resistance was mainly led by Ahmed Bey ben Mohamed Chérif in the east and nationalist forces in the west. Treaties with the nationalists under Emir Abdelkader allowed the French to focus on defeating the remaining forces in the east during the 1837 Siege of Constantine. Abdelkader continued to fight the French in the west until 1847.

Many Algerians died during the French conquest due to war, massacres, disease, and famine. Famines and diseases were partly caused by France taking farmland from Algerians and using "scorched earth" tactics (burning farms and villages) to stop resistance.

By 1852, there were about 100,000 European settlers in Algeria, about half of them French. Under the Second Republic, the country was ruled by a civilian government. But Louis Napoleon brought back military rule, which annoyed the colonists. By 1857, the army had taken over Kabyle Province and brought peace to the country. By 1860, the European population had grown to 200,000. Lands belonging to native Algerians were quickly being bought by the new arrivals.

At first, Napoleon III did not pay much attention to Algeria. But in September 1860, he and Empress Eugénie visited Algeria. This trip made a big impression on them. Napoleon III began to think that Algeria should be governed differently from other colonies. In February 1863, he wrote that "Algeria is not a colony in the traditional sense, but an Arab kingdom." He said that the local people had a right to his protection, just like the French. He wanted to rule Algeria through Arab leaders. He invited the chiefs of main Algerian tribes to his palace for hunting and parties.

Compared to earlier rulers, Napoleon III was more understanding towards native Algerians. He stopped Europeans from moving further inland, keeping them to the coastal areas. He also freed the Algerian rebel leader Abd al Qadir and gave him money. He allowed Muslims to serve in the military and civil service on equal terms and to move to France. He also offered citizenship. However, for Muslims to become citizens, they had to accept all French laws, including those about inheritance and marriage, which went against Muslim laws. This was seen by some Muslims as giving up parts of their religion to get citizenship, and they did not like it.

More importantly, Napoleon III changed how land was owned. While he meant well, this change destroyed the traditional way of managing land and took land away from many Algerians. Napoleon gave up state claims to tribal lands, but he also started to break up tribal land ownership into individual ownership. French officials, who supported the French in Algeria, misused this process and took much of the land for public use. Also, many tribal leaders, chosen for their loyalty to the French rather than their influence in their tribe, quickly sold communal land for cash.

His attempts at reform were stopped in 1864 by an Arab uprising. It took more than a year and an army of 85,000 soldiers to stop it. Still, he did not give up his idea of making Algeria a place where French colonists and Arabs could live and work together as equals. He traveled to Algiers a second time in May 1865 and stayed for a month. He met with tribal leaders and local officials. He offered forgiveness to those who took part in the uprising and promised to appoint Arabs to high positions in his government. He also promised a large program of new ports, railroads, and roads. However, his plans faced natural problems in 1866 and 1868. Algeria was hit by a cholera epidemic, locusts, drought, and famine. His reforms were also hindered by the French colonists, who voted against him. Many people died from the famine and epidemics.

In 1871, due to long famine and unfair treatment of Algerians by French authorities, the Mokrani Revolt started in Kabylia. It spread through much of Algeria. By April 1871, 250 tribes were rebelling. The uprising was defeated in 1872. There were about 130,000 colonists in Algeria in 1871, and by 1900, there were one million. In 1902, a French military group entered the Hoggar Mountains and defeated the kingdom of Kel Ahaggar. The conquest of Algeria was completed in 1920 when the Kel Ajjer stopped their resistance to French rule.

More French Colonization in Africa

France also expanded its influence in North Africa after 1870. It set up a protectorate in Tunisia in 1881 with the Bardo Treaty. Gradually, French control became strong over much of North, West, and Central Africa by the early 1900s. This included modern states like Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea, Mali, Ivory Coast, Benin, Niger, Chad, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, the East African coastal area of Djibouti, and the island of Madagascar.

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza helped France gain control in Gabon and on the northern banks of the Congo River starting in the early 1880s. The explorer Colonel Parfait-Louis Monteil traveled from Senegal to Lake Chad in 1890–1892. He signed friendship and protection treaties with rulers of several countries he passed through. He also learned a lot about the geography and politics of the region.

The Voulet–Chanoine Mission, a military expedition, left Senegal in 1898. Its goal was to conquer the Chad Basin and unite all French territories in West Africa. This expedition worked with two others, the Foureau–Lamy and Gentil Missions, which came from Algeria and Middle Congo. When the Muslim warlord Rabih az-Zubayr, the greatest ruler in the region, died in April 1900, and the Military Territory of Chad was created in September 1900, the Voulet–Chanoine Mission had achieved its goals. However, the mission's harshness caused a scandal in Paris.

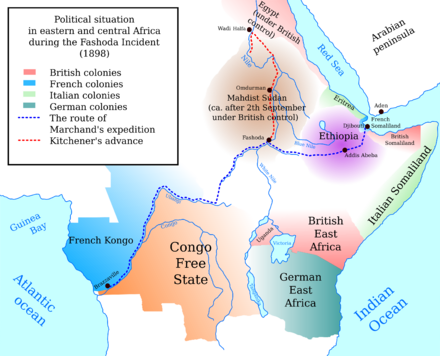

As part of the "Scramble for Africa", France wanted to create a continuous west-to-east area across the continent. This was different from Britain's plan for a north-to-south area. Tensions between Britain and France grew in Africa. At times, war seemed possible, but it did not happen. The most serious event was the Fashoda Incident of 1898. French troops tried to claim an area in Southern Sudan. A British force arrived to confront them. Under pressure, the French pulled back, accepting British control over the area. An agreement between the two countries recognized the existing situation. The British would control Egypt, while France remained powerful in Morocco. Many believed France suffered a humiliating defeat.

During the Agadir Crisis in 1911, Britain supported France against Germany. Morocco then became a French protectorate. France made its last major colonial gains after World War I. It gained control over former territories of the Ottoman Empire that are now Syria and Lebanon. It also took most of the former German colonies of Togo and Cameroon.

French Colonies in the Pacific Islands

In 1838, French naval commander Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars heard complaints about how French Catholic missionaries were treated in the Kingdom of Tahiti. He forced the local government to pay money and sign a friendship treaty with France. This treaty respected the rights of French people on the islands, including future Catholic missionaries. Four years later, claiming the Tahitians had broken the treaty, France forced a protectorate on the island. The queen was made to sign a request for French protection.

Queen Pōmare left her kingdom and went to Raiatea to protest against the French. She tried to get help from Queen Victoria. The Franco-Tahitian War broke out between the Tahitian people and the French from 1844 to 1847. France tried to strengthen its rule and expand into the Leeward Islands, where Queen Pōmare had sought safety. Britain remained neutral but had diplomatic tensions with France. The French managed to defeat the local fighters on Tahiti but failed to hold the other islands. In February 1847, Queen Pōmare IV returned and agreed to rule under the protectorate. Even though France won, it could not take over the islands completely due to British pressure. So, Tahiti and Moorea continued to be ruled under the protectorate. An agreement called the Jarnac Convention (or Anglo-French Convention of 1847) was signed by France and Britain. In this agreement, both powers agreed to respect the independence of Queen Pōmare's allies in the Leeward Islands. The French continued their "protection" until the 1880s. They formally took over Tahiti when King Pōmare V gave up his throne on June 29, 1880. The Leeward Islands were taken over through the Leewards War, which ended in 1897. These conflicts and the taking of other Pacific islands formed French Oceania.

On September 24, 1853, Admiral Febvrier Despointes officially took control of New Caledonia. Port-de-France (now Nouméa) was founded on June 25, 1854. A few free settlers moved to the west coast in the following years. But New Caledonia became a penal colony (a place for prisoners). From the 1860s until 1897, about 22,000 criminals and political prisoners were sent there.

Against the 1847 Jarnac Convention, the French put the Leeward Islands under a temporary protectorate. They falsely convinced the ruling chiefs that the German Empire planned to take over their islands. After years of talks, Britain and France agreed to cancel the convention in 1887. The French then officially took over all the Leeward Islands without formal agreements from the islands' governments. From 1888 to 1897, the people of Raiatea and Tahaa, led by a chief named Teraupo'o, fought against French rule. Anti-French groups in Huahine also tried to fight the French under Queen Teuhe. The kingdom of Bora Bora stayed neutral but was against the French. The conflict ended in 1897 when rebel leaders were captured and sent away to New Caledonia and the Marquesas. These conflicts and the taking of other Pacific islands formed French Polynesia.

At this time, the French also set up colonies in the South Pacific. These included New Caledonia, the various island groups that make up French Polynesia (like the Society Islands and the Marquesas). They also shared control of the New Hebrides with Britain.

Napoleon III's Expansion (1852–1870)

Napoleon III doubled the size of the French overseas Empire. He established French rule in New Caledonia and Cochinchina. He also set up a protectorate in Cambodia (1863) and colonized parts of Africa.

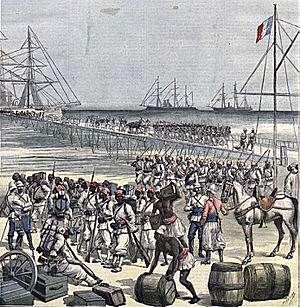

To achieve his new overseas goals, Napoleon III created a new Ministry of the Navy and the Colonies. He appointed Prosper, Marquis of Chasseloup-Laubat, an energetic minister, to lead it. A key part of this effort was to modernize the French Navy. He started building 15 powerful new battle cruisers powered by steam and propellers. He also built a fleet of steam-powered troop transport ships. The French Navy became the second most powerful in the world, after Britain's. He also created new colonial troops, including special units like naval infantry and the Foreign Legion. By the end of Napoleon III's rule, the French overseas territories had tripled in size. In 1870, they covered about 1,000,000 square kilometers and had over 5 million people.

French Colonies in Asia

Napoleon III also worked to increase France's presence in Indochina. He believed France would become less important if it did not expand its influence in East Asia. He also felt France had a duty to bring its culture to the world.

French missionaries had been active in Vietnam since the 1600s. In 1858, the Vietnamese emperor felt threatened by French influence and tried to remove the missionaries. Napoleon III sent a naval force to make the government accept the missionaries and stop persecuting Catholics. In September 1858, the force captured the port of Da Nang. In February 1859, they moved south and captured Saigon. The Vietnamese ruler was forced to give three provinces to France and protect Catholics. The French troops left for a time to join an expedition to China. But in 1862, when the Vietnamese emperor did not fully follow the agreements, they returned. The Emperor was forced to open treaty ports in Annam and Tonkin. All of Cochinchina became French territory in 1864.

In 1863, the ruler of Cambodia, King Norodom, who was put in power by Thailand, rebelled against Thailand and sought France's protection. The Thai king gave authority over Cambodia to France. In return, France gave two provinces of Laos to Thailand. In 1867, Cambodia officially became a protectorate of France.

Most of France's later colonial lands were gained after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) and the start of the Third Republic (1871–1940). From their base in Cochinchina, the French took over Tonkin (northern Vietnam) and Annam (central Vietnam). These became French protectorates with the Treaty of Hue in 1883. These areas, along with Cambodia and Cochinchina, formed French Indochina in 1887. Laos was added in 1893 and Guangzhouwan in 1900.

In 1849, the French Concession in Shanghai was set up. In 1860, the French Concession in Tientsin (now Tianjin) was created. Both lasted until 1946. The French also had smaller areas of control in Guangzhou and Hankou (now part of Wuhan).

The Third Anglo-Burmese War, where Britain conquered Upper Burma, was partly because Britain worried about France gaining lands near Burma.

French Colonies in the Middle East

In spring 1860, a war started in Lebanon, then part of the Ottoman Empire. It was between the Druze people and the Maronite Christians. The Ottoman authorities could not stop the violence, and it spread to Syria. Many Christians were killed. In Damascus, Emir Abd-el-Kadr protected the Christians from Muslim rioters. Napoleon III felt he had to help the Christians, even though London was against it. After long talks, Napoleon III sent 7,000 French soldiers for six months. The troops arrived in Beirut in August 1860 and took positions between the Christian and Muslim communities. Napoleon III organized a conference in Paris. The country was placed under a Christian governor chosen by the Ottoman Sultan, which brought a fragile peace. The French troops left in June 1861. This French action worried the British. But it was very popular with the powerful Catholic group in France.

Despite a free trade agreement between Britain and France in 1860, and joint operations in Crimea, China, and Mexico, their diplomatic relations were never very close during the colonial era. Lord Palmerston, the British foreign minister and prime minister, wanted to keep a balance of power in Europe. This rarely involved working with France. In 1859, there were even brief fears that France might try to invade Britain. Palmerston was suspicious of France's actions in Lebanon, Southeast Asia, and Mexico. He also worried that France might get involved in the American Civil War (1861–65) on the side of the South. The British also felt threatened by the building of the Suez Canal (1859–1869) by Ferdinand de Lesseps in Egypt. They tried to stop its completion.

The Suez Canal was successfully built by a French-backed company. It remained under French control even after the British government bought almost half of the shares. Both nations saw the canal as vital for keeping their influence and empires in East Africa and Asia. In 1882, unrest in Egypt led Britain to intervene, asking France for help. France's main expansionist leader, Jules Ferry, was not in office, so Paris allowed London to take control of Egypt.

The Term "Empire" (1870–1939)

After Napoleon III's fall, few writers used the word "empire." It was linked to harsh rule and weakness. They preferred "colonies." But by the 1880s and 1890s, as Republicans gained power, more politicians and writers started using "colonial empire." They linked it to the idea of a strong French nation.

Most French people did not pay much attention to foreign affairs or colonial issues. In 1914, the main group pushing for colonies was the Parti colonial. It was a group of 50 organizations with only 5,000 members.

Reasons and Justifications for Colonialism

The Civilizing Mission

A key idea of French colonialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the "civilising mission" (mission civilisatrice). This was the belief that it was Europe's duty to bring civilization to other peoples. So, French colonial officials tried to make French colonies, especially French West Africa and Madagascar, more like France. In the 19th century, people in the old colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyanne, Réunion, French India, and the "Four Communes" in Senegal were given French citizenship. They also had the right to elect a representative to the French Parliament. Most of these elected representatives were white Frenchmen, but some were black, like Blaise Diagne from Senegal.

Racism and ideas of white supremacy were central to justifying the civilizing mission. French colonialists saw non-European societies as uncivilized. They believed their colonial subjects needed European re-education. Some thinkers falsely claimed that people of color were biologically less capable than white people.

In the largest and most populated colonies, there was a strict separation. People were either "French subjects" (natives) or "French citizens" (people of European background). They had different rights and duties until 1946. Granting French citizenship to natives was seen as a "privilege," not a right. Two decrees in 1912 listed the conditions for natives to get French citizenship. These included speaking and writing French, earning a good living, and showing good morals. From 1830 to 1946, only a few thousand Muslim native Algerians became French citizens. In French West Africa, outside the Four Communes, there were only 2,500 "native citizens" out of 15 million people.

French conservatives criticized the idea of assimilation. They saw it as a dangerous fantasy. In the Protectorate of Morocco, the French administration tried to use city planning and colonial education to prevent cultures from mixing. They wanted to keep the traditional society that they relied on for cooperation. After World War II, the idea of segregation was seen as bad. Assimilation then became popular again for a short time.

Historian David P. Forsythe wrote that in French Africa, there were many destructive wars. These wars led to many people being forced into slavery. At the start of the 20th century, there may have been between 3 and 3.5 million enslaved people in this region. This was over 30% of the total population. In 1905, the French abolished slavery in most of French West Africa. From 1906 to 1911, over a million enslaved people in French West Africa escaped from their masters. In Madagascar, over 500,000 enslaved people were freed after France abolished slavery there in 1896.

Education in the Colonies

French colonial officials wanted to make schools, lessons, and teaching methods the same everywhere. They did not set up colonial schools to help local people achieve their goals. Instead, they simply brought the school systems from France to the colonies. Having a moderately trained local staff was very useful for colonial officials. The new French-educated local leaders did not see much value in educating people in rural areas. After 1946, the policy was to send the best students to Paris for advanced training. This led to the next generation of leaders becoming part of the growing anti-colonial movement based in Paris. For example, Ho Chi Minh and other young activists in Paris formed the French Communist party in 1920.

Tunisia was different. The colony was managed by Paul Cambon, who built an education system for both colonists and local people that was very similar to France's. He focused on education for girls and job training. By the time Tunisia became independent, its education quality was almost as good as in France.

African nationalists did not like this public education system. They saw it as a way to slow down African development and keep colonial power. After World War II, one of the first demands of the growing nationalist movement was for full French-style education in French West Africa. They believed this would bring equality with Europeans.

In Algeria, the debate was very divided. The French set up schools based on science and French culture. The Pied-Noir (Catholic people from Europe) liked this. But the Muslim Arabs did not. They valued their own distinct religious traditions. The Arabs refused to become patriotic Frenchmen. A single education system was not possible until the Pied-Noir and their Arab allies left after 1962.

Critics of French Colonialism

Critics of French colonialism became well-known in the 1920s. They often used reports and worked with groups like the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization to make their protests heard. The main criticism was the high level of violence and suffering among the native people. Important critics included Albert Londres, Félicien Challaye, and Paul Monet. Their books and articles were widely read.

Decolonization

The French colonial empire began to weaken during World War II. Various parts were taken over by other countries. For example, Japan took parts of Indochina, Britain took Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, and Germany and Italy took Tunisia. However, Charles de Gaulle gradually regained control. The French Union, part of the Constitution of 1946, officially replaced the old colonial empire. But officials in Paris still had full control. The colonies were given local assemblies with only limited power and budgets. A group of educated local elites, called "evolués," emerged.

World War II and the Colonies

During World War II, the Allied Free France (often with British help) and the Axis-aligned Vichy France fought for control of the colonies. Sometimes, there was direct military combat. By 1943, all colonies, except Indochina (which was under Japanese control), had joined the Free French side.

The overseas empire helped free France. For example, 300,000 North African Arabs fought with the Free French. However, Charles de Gaulle did not plan to free the colonies. He gathered colonial governors in Brazzaville in January 1944 to announce plans for a postwar Union. This Union would replace the Empire. The Brazzaville manifesto stated that France's goals in the colonies did not include independence. It said there was no possibility for colonies to develop outside the French Empire. This angered nationalists across the Empire and led to long wars in Indochina and Algeria, which France would lose.

Conflicts and Independence

France immediately faced the start of the decolonisation movement. In Algeria, protests in May 1945 were put down. Many Algerians were killed. Unrest in Haiphong, Indochina, in November 1945 was met by a warship firing on the city. Paul Ramadier's government also put down the Malagasy Uprising in Madagascar in 1947. French officials estimated that many Malagasy people were killed.

In Indochina, Ho Chi Minh's Viet Minh, supported by the Soviet Union and China, declared Vietnam's independence. This started the First Indochina War. The war lasted until 1954, when the Viet Minh defeated the French at the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ in northern Vietnam. This was the last major battle of the war.

After the Vietnamese victory at Điện Biên Phủ and the signing of the 1954 Geneva Accords, France agreed to pull its forces out of all its colonies in French Indochina. Vietnam was temporarily divided at the 17th parallel. The north was controlled by the Soviet-backed Viet Minh under Ho Chi Minh. The south became the State of Vietnam under former Emperor Bảo Đại. However, in 1955, the Prime Minister of the State of Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm, removed Bảo Đại and declared himself president of the new Republic of Vietnam. His refusal to allow elections in 1956, as agreed at Geneva, led to the Vietnam War.

In France's African colonies, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon's uprising, which began in 1955, was violently put down over two years. Many people were killed. However, France officially gave up its protectorate over Morocco and granted it independence in 1956.

French involvement in Algeria went back a century. The movements of Ferhat Abbas and Messali Hadj had been active between the two world wars. But both sides became more extreme after World War II. In 1945, the Sétif massacre was carried out by the French army. The Algerian War started in 1954. Both sides committed harsh acts. The number of people killed became a very debated topic. Algeria was a three-sided conflict because of the large number of "pieds-noirs" (Europeans who had settled there during 125 years of French rule). The political crisis in France caused the fall of the Fourth Republic. Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958 and finally pulled French soldiers and settlers out of Algeria by 1962.

The French Union was replaced by the French Community in the Constitution of 1958. Only Guinea voted against joining the new organization. However, the French Community stopped working before the end of the Algerian War. Almost all other former African colonies gained independence in 1960. The French government did not allow people in the former colonies the right to become full "departments" of France, even though they were French citizens with equal rights under the new constitution. The French government passed a law that removed the need for a vote to confirm a change in status towards independence. So, voters who had rejected independence in 1958 were not asked about it in 1960. A few former colonies chose to remain part of France as overseas "departments" or territories.

Critics of neocolonialism claimed that Françafrique had replaced formal direct rule. They argued that while de Gaulle was granting independence, he was keeping French power through the actions of Jacques Foccart, his advisor for African matters. Foccart supported Biafra in the Nigerian Civil War in the late 1960s.

Robert Aldrich argues that with Algeria's independence in 1962, the Empire seemed to have ended. The remaining colonies were small and did not have strong nationalist movements. However, there was trouble in French Somaliland (Djibouti), which became independent in 1977. There were also problems and delays in the New Hebrides (Vanuatu), which was the last to gain independence in 1980. New Caledonia remains a special case under French control. The Indian Ocean island of Mayotte voted in 1974 to stay linked with France and not become independent like the other three islands of the Comoro archipelago.

Demographics

French census data from 1936 shows that the French Empire, outside of France itself, had 69.1 million people. Of these, 16.1 million lived in North Africa, 25.5 million in sub-Saharan Africa, 3.2 million in the Middle East, 0.3 million in India, 23.2 million in East and South-East Asia, 0.15 million in the South Pacific, and 0.6 million in the Caribbean.

The largest colonies were French Indochina (with five separate colonies and protectorates), with 23.0 million people. Next was French West Africa (eight separate colonies), with 14.9 million. Algeria (three departments and four Saharan territories) had 7.2 million. The protectorate of Morocco had 6.3 million. French Equatorial Africa (four separate colonies) had 3.9 million. And Madagascar and Dependencies (including the Comoro Islands) had 3.8 million.

In 1936, 2.7 million Europeans (French and non-French citizens) and assimilated natives (non-European French citizens) lived in the French colonial empire. There were also 66.4 million non-assimilated natives (French subjects but not citizens). Most Europeans lived in North Africa. Non-European French citizens mainly lived in the four "old colonies" (Réunion, Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French Guiana). They also lived in the Four Communes of Senegal (Saint-Louis, Dakar, Gorée, and Rufisque) and in the South Pacific colonies.

| 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan France | 39,140,000 | 40,710,000 | 41,550,000 | 41,500,000 |

| Colonies, protectorates, and mandates | 55,556,000 | 59,474,000 | 64,293,000 | 69,131,000 |

| Total | 94,696,000 | 100,184,000 | 105,843,000 | 110,631,000 |

| Percentage of the world population | 5.02% | 5.01% | 5.11% | 5.15% |

| Sources: INSEE, SGF | ||||

French Settlers

Unlike other European countries, France had relatively few people move to the Americas, except for the Huguenots who went to British or Dutch colonies. France generally had very slow population growth in Europe, so there was not much pressure for people to leave. A small but important number of mainly Roman Catholic French people, only tens of thousands, settled in Acadia, Canada, and Louisiana. They also settled in colonies in the West Indies, Mascarene islands, and Africa. In New France, Huguenots were not allowed to settle. Quebec was one of the most strongly Catholic areas in the world until the Quiet Revolution. The current French Canadian population, which numbers in the millions, is almost entirely descended from New France's small settler population.

On December 31, 1687, a group of French Huguenots settled in South Africa. Most of them first settled in the Cape Colony. They were quickly absorbed into the Afrikaner population. After Champlain founded Quebec City in 1608, it became the capital of New France. Encouraging settlement was hard. By 1763, New France only had about 65,000 people.

In 1787, there were 30,000 white colonists on France's colony of Saint-Domingue. In 1804, Dessalines, the first ruler of independent Haiti (Saint-Domingue), ordered the killing of white people remaining on the island. Out of 40,000 people on Guadeloupe at the end of the 17th century, over 26,000 were black and 9,000 were white. Bill Marshall wrote that the first French attempt to colonize Guiana in 1763 failed completely. Tropical diseases and the climate killed all but 2,000 of the first 12,000 settlers.

French law made it easy for thousands of colons (ethnic French people from former colonies in North and West Africa, India, and Indochina) to live in mainland France. It is estimated that 20,000 colons lived in Saigon in 1945. 1.6 million European pieds noirs moved from Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco. In just a few months in 1962, 900,000 French Algerians left Algeria. This was the largest population movement in Europe since World War II. In the 1970s, over 30,000 French colons left Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge rule, as the Pol Pot government took their farms and land. In November 2004, several thousand of the estimated 14,000 French nationals in Ivory Coast left the country after days of anti-white violence.

Besides French-Canadians (Québécois and Acadians), French-speaking Louisianians (Cajuns and Louisiana Creoles), and Métis, other populations of French origin outside France include the Caldoches of New Caledonia. There are also the Zoreilles, Petits-blancs, Franco-Mauritians of various Indian Ocean islands, and the Beke people of the French West Indies.

Territories

Africa

- French Algeria (1830–1961)

- French Military Territory in Libya (1943–1951)

- French Protectorate in Morocco (1912–1956)

- French Protectorate of Tunisia (1881–1956)

- French West Africa (1895–1958)

- French Mauritania (1958–1960)

- French Senegal (1958–1960)

- French Guinea (1958–1960)

- French Ivory Coast (1958–1960)

- French Niger (1958–1960)

- French Upper Volta (1958–1960)

- French Dahomey (1958–1960)

- French Togoland (1958–1960)

- French Sudan (1959–1960)

- French Equatorial Africa (1910–1958)

- French Gabon (1958–1960)

- French Congo (1958–1960)

- Ubangui-Shari (1958–1960)

- French Chad (1958–1960)

- French Cameroon (1920–1960)

- French Madagascar (1897–1958)

- Seychelles (1756–1794)

- Île de France (Mauritius) (1715–1810)

- Comoros (1841–1975)

- Mayotte (1843–)

- Réunion (1665–)

- Kerguelen (1924–)

- Île Saint-Paul (1924–)

- Amsterdam Island (1924–)

- Crozet Islands (1772–)

- Bassas da India (1897–)

- Europa Island (1897 )

- Juan de Nova Island (1897–)

- Glorioso Islands (1892–)

- Tromelin (1722–)

- French Somalia (1896–1967)

- French domains of St Helena (1854–)

Asia

- French mandate of Syria (1923–1946)

- Greater Lebanon (1923–1943)

- French India (1673–1950)

- French Indochina (1887–1954)

- French Cochinchina (1862–1946)

- Tonkin (1883–1887)

- Annam (1883–1950)

- French protectorate of Cambodia (1863–1956)

- French protectorate of Laos (1893–1953)

- Leased territory of Guangzhouwan (1898–1945)

- China concessions

- French concession in Tianjin (1896–1943)

- Shanghai French Concession (1896–1943)

- Shamian Island, Guangzhou (1896–1943)

The Caribbean

- Commonwealth of Dominica (1690–1763)

- Grenada (1649–1763)

- Guadeloupe (1635–)

- Haiti (1697–1804)

- Martinique (1635–)

- Saint Barthélemy (1878–)

- Saint Lucia (1674–1814)

- Saint Martin (1648–)

- Dominican Republic (1795–1815)

- Virgin Islands

- Saint Croix (1664–1733)

- Vieques (1698–1811)

South America

- France Antarctique (1555–1567)

- French Guiana (1503–)

- Equinoctial France (1612–1615)

North America

- New France (1534–1763)

- Acadia (1604–1713)

- Illinois Country (1675–1769), (1801–1803)

- Canada (1535–1763)

- Louisiana (1682–1762), (1801–1803)

- Newfoundland (1658–1713)

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon (1536–)

Oceania

- New Caledonia (1853–)

- French Polynesia (1842–)

- Wallis and Futuna (1887–)

- Clipperton Island (1858–)

- New Hebrides (1887–1980)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Imperio colonial francés para niños

In Spanish: Imperio colonial francés para niños

- Army of the Levant

- CFA franc

- Colonialism

- Decolonization

- Evolution of the French Empire

- Francization

- French Army units with a tradition of service overseas

- 1900–1958: Troupes de marine

- 1900–1958: Troupes coloniales

- Tirailleurs

- Spahis

- Zouaves

- French colonial flags

- French colonisation of the Americas

- French law on colonialism (for teachers, 2005)

- History of France

- International relations (1814–1919)

- List of French possessions and colonies

- New France

- Organisation internationale de la Francophonie

- Overseas France

- Postage stamps of the French colonies

- Scramble for Africa

- Timeline of imperialism

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |