Third Anglo-Burmese War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Third Anglo-Burmese Warတတိယ အင်္ဂလိပ် - မြန်မာစစ် |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

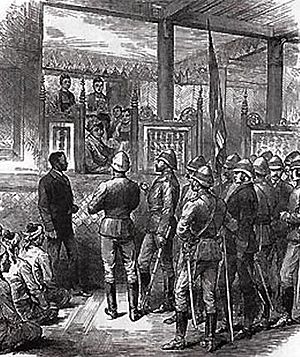

The nominal surrender of the Burmese Army, 27 November 1885, at Ava. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The Third Anglo-Burmese War (Burmese: တတိယ အင်္ဂလိပ် – မြန်မာစစ်, romanized: Tatiya Anggalip–Mran cac), also known as the Third Burma War, was a short but important conflict. It took place from November 7 to November 29, 1885. This war was the last of three wars fought between the Burmese people and the British Empire in the 1800s.

After this war, Burma lost its independence. The Konbaung dynasty stopped ruling, and the British took control. Burma became a part of British India. Later, in 1937, the British ruled Burma as a separate colony. Burma finally became an independent country in 1948.

Contents

Why the War Started

After some problems about who would be the next king in Burma in 1878, the British official living in Burma left. This ended the official talks between the two countries. The British thought about starting a new war. However, they were already fighting wars in Africa and Afghanistan, so they decided not to at that time.

French Influence in Burma

In the 1880s, the British worried about Burma's connections with France. France had been expanding its control in nearby Indochina. In May 1883, a group of Burmese officials went to Europe. They said they wanted to learn about new industries. But they soon went to Paris and started talking with the French Foreign Minister, Jules Ferry.

Ferry later told the British ambassador that the Burmese were trying to make a political alliance. They also wanted to buy military equipment from France. The British were very concerned by this. Relations between Britain and Burma became worse.

Border Disputes and British Demands

While the French and Burmese were talking, a disagreement about the border between India and Burma started. In 1881, British officials in India decided to mark the border on their own. They started telling Burmese villages on their side of the line to move. The Burmese protested, but eventually gave in.

In 1885, a French official named M. Hass moved to Mandalay, Burma's capital. He tried to set up a French Bank in Burma. He also wanted permission for a railway from Mandalay to the British border. He also wanted France to help manage businesses controlled by the Burmese government. The British strongly objected. They convinced the French government to call Hass back home.

Even though France backed down, these events made the British decide to act against Burma.

The Teak Dispute and Ultimatum

A British company called the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation was fined by a Burmese court. The court said the company had not reported all the teak wood it took from Toungoo. It also said the company had not paid its workers enough. Some of the company's wood was taken by Burmese officials.

The company and the British government said these charges were false. They also claimed the Burmese courts were corrupt. The British demanded that the Burmese government let a British person settle the dispute. When the Burmese refused, the British sent a final demand on October 22, 1885.

This demand said that Burma must:

- Accept a new British official in Mandalay.

- Stop all legal actions against the company until the official arrived.

- Let Britain control Burma's foreign relations.

- Allow Britain to develop trade between northern Burma and China.

If Burma accepted these demands, it would lose its real independence. It would become like the semi-independent states within British India. By November 9, the British in Rangoon knew that Burma had practically refused their terms. So, they decided to take Mandalay and remove King Thibaw Min from power. They likely also decided to take over the entire Burmese kingdom.

The War Begins

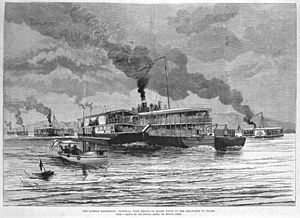

At this time, Burma was mostly dense jungle. This made military actions difficult. The British did not know much about Upper Burma. However, British ships had been using the Irrawaddy River for years. This river went from Rangoon all the way to Mandalay. So, the British knew that the fastest way to win the war was to advance directly to the capital by water.

The Irrawaddy Flotilla Company had many small river steamers and barges in Rangoon. These were perfect for moving troops and supplies. The company's officers also knew the river very well.

British Forces and Rapid Advance

Major-General Harry Prendergast was put in charge of the invasion. Both the navy and the army were needed. The navy's ships and guns were very important. The British had 3,029 British soldiers, 6,005 Indian soldiers, and 67 guns. For river fighting, they had 24 machine guns. The river fleet had over 55 steamers, barges, and other boats to carry the troops and supplies.

Thayetmyo was the closest British post on the river to the border. By November 14, just five days after King Thibaw's refusal, almost the entire British force was gathered there. On the same day, General Prendergast was told to start the attack.

The Burmese king and his country were completely surprised by how fast the British moved. They did not have time to get ready or organize their defenses. They could not even block the river by sinking ships. On the very day the British got their orders, armed steamers attacked the nearest Burmese forts. They pulled out the Burmese King's steamer and some barges that were ready to block the river.

On November 16, the British took the Burmese forts on both sides of the river. The Burmese were not ready and did not fight back.

Battle of Minhla

However, on November 17, at Minhla, the Burmese fought back strongly. They held a barricade, a pagoda, and a fort. British Indian soldiers attacked on land, while ships fired from the river. The Burmese were defeated. They lost 170 killed and 276 prisoners. Many more drowned trying to escape by river.

The British continued their advance in the following days. Their naval ships and heavy guns led the way. They quickly silenced the Burmese river defenses at Nyaung-U, Pakokku, and Myingyan.

Burmese Resistance and Treachery

Some people say that the Burmese did not fight very hard because King Thibaw's defense minister, Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung, wanted to make peace with the British. He ordered Burmese troops not to attack the British. Some troops obeyed, but not all.

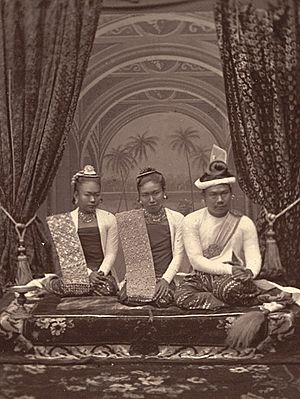

Also, the British spread stories as they marched through Burma. They told the Burmese that they did not want to take over the country. Instead, they claimed they only wanted to remove King Thibaw and put Prince Nyaungyan on the throne. Prince Nyaungyan was an older half-brother of Thibaw. Many Burmese did not like King Thibaw because his government was poorly managed. Also, when he became king in 1878, many royal family members were killed. Nyaungyan had survived this and was living in British India.

Actually, Prince Nyaungyan was already dead by this time. But the British kept this a secret. Some sources say the British even brought a man pretending to be Prince Nyaungyan with them. This made the Burmese believe the story about a new king. So, many Burmese welcomed the British and did not fight them.

However, when it became clear that the British were not putting a new king on the throne and were taking over Burma, fierce rebellions started. These rebellions, by former royal Burmese army troops and other groups, lasted for more than ten years. U Kaung's actions in the early part of the war led to a popular saying: U Kaung lein htouk, minzet pyouk ("U Kaung's treachery, end of dynasty").

On November 26, as the British ships neared the capital Ava, King Thibaw sent people to meet General Prendergast. They offered to surrender. On November 27, when the ships were ready to attack, the king ordered his troops to put down their weapons. There were three strong forts with thousands of armed Burmese soldiers. Many of them did lay down their arms as ordered. However, many more were allowed to leave with their weapons. These soldiers later formed groups that fought the British for years.

Meanwhile, the surrender of the king was complete. On November 28, less than two weeks after the war began, Mandalay had fallen. King Thibaw was taken prisoner. All the strong forts and towns on the river were captured. The British also took all the king's weapons (1861 pieces), and thousands of rifles and muskets. Most of these were found in the Mandalay palace and the city itself. These items were later sold for a large profit.

From Mandalay, General Prendergast reached Bhamo on December 28. This was an important move because it stopped the Chinese, who also had claims and border disputes with Burma. Even though the king was removed and sent away to India, and the British controlled the capital and the river, groups of rebels continued to fight. These groups were very hard to defeat.

Taking Over and Fighting Back

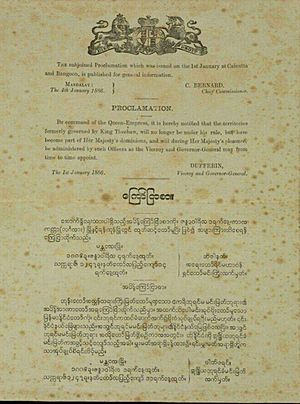

Burma was officially taken over by the British on January 1, 1886. This was announced by Lord Dufferin, the Viceroy and Governor-General of India.

PROCLAMATION.

By command of the Queen-Empress, it is hereby notified that the territories formerly governed by King Theebaw, will no longer be under his rule, but have become part of Her Majesty's dominions, and will during Her Majesty's pleasure, be administered by such Officers as the Viceroy and Governor-General may from time to time appoint.

The 1st January 1886.

DUFFERIN,

Viceroy and Governor-General.

This takeover started a resistance movement against the British that lasted until 1896. To finally conquer the country, Sir Frederick Roberts used many small military police posts spread across the country. Small, lightly armed groups of soldiers would move out whenever groups of freedom fighters gathered. The British sent more soldiers into Burma. This phase of the campaign, which lasted several years, was the most difficult and brutal for the British and Indian troops. Even with Roberts' efforts, the freedom fighters in Burma remained active for another ten years.

The British also took control of the tribal areas in the Kachin Hills and Chin Hills. These areas were only loosely ruled by the Burmese kingdom before. The British also took disputed lands in northern Burma that the Chinese government claimed.

An important early land advance happened in November 1885 from Toungoo, a British border post in eastern Burma. A small group of soldiers led by Colonel W. P. Dicken moved towards Ningyan (Pyinmana). They successfully stopped the freedom fighters, despite some resistance. The force then moved on to Yamethin and Hlaingdet. As fighting moved inland, the British realized they needed more mounted troops (soldiers on horses). Several cavalry regiments were brought from India, and mounted infantry were recruited locally. The British found that without mounted troops, it was generally impossible to fight the Burmese successfully.

What Happened to Burmese Treasures?

After Burma was taken over, valuable items belonging to the Burmese government were taken by the British. Many things that were easy to move, like gold, jewelry, silk, and decorative objects, were sent back to Britain. They were given as gifts to the royal family and important people in Britain. Other items were sold in auctions.

An organization called the "Prize Committee, Mandalay" was set up to sell off the former Burmese government's possessions. Most of the auctioned items were bought by British army and navy officers, civil servants, and some European travelers.

Items made of valuable metals that were damaged or not considered artistic were melted down for their metal. Very valuable items were sent to a British engineer in Calcutta, India. Some items of high religious importance, including 11 gold statues of Lord Buddha, were kept by the Calcutta museum. They were to be restored and, if asked for later, returned to the descendants of Burmese royalty. Machinery, steamers, and useful items were usually given to the British government or bought at very low prices. Guns, cannons, and field guns were mostly destroyed or thrown into deep water.

In 1886, a military trip was made to open up the valuable ruby mines at Mogok. This was so British merchants could use them. George Skelton Streeter, an expert in gems, went with the trip. He stayed there to work as a government valuer in the British-run mines.

See also

- History of Burma

- Konbaung dynasty

- First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826)

- Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852–1853)

- British rule in Burma

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |