Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

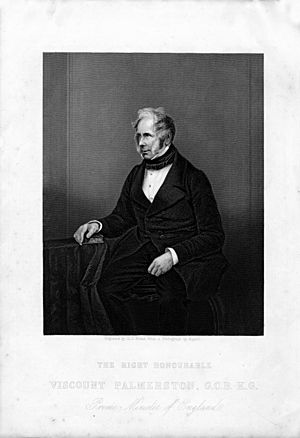

The Viscount Palmerston

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

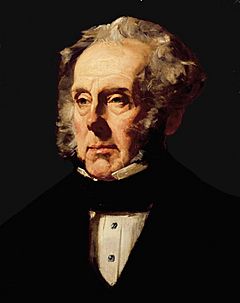

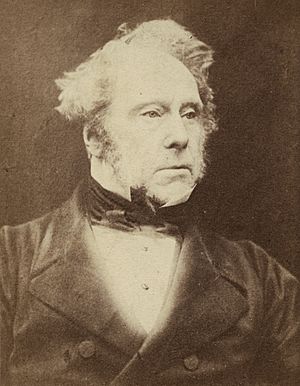

Lord Palmerston, c. 1857

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 June 1859 – 18 October 1865 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Earl of Derby | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Earl Russell | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 February 1855 – 19 February 1858 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Earl of Aberdeen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Derby | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 20 October 1784 Westminster, Middlesex, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 18 October 1865 (aged 80) Brocket Hall, Hertfordshire, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | Harry | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (born October 20, 1784 – died October 18, 1865) was an important British leader in the mid-1800s. He served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Palmerston was in charge of Britain's foreign policy from 1830 to 1865. This was a time when Britain was very powerful around the world.

He held government jobs almost continuously from 1807 until he passed away in 1865. He started his political life as a Tory, then joined the Whigs in 1830. In 1859, he became the first prime minister from the new Liberal Party. People in Britain really liked him. Many historians say his energy and strength made him very popular.

Henry Temple became the 3rd Viscount Palmerston in 1802 after his father died. This Irish title did not give him a seat in the House of Lords. This meant he could be a member of the House of Commons. He became a Tory Member of Parliament (MP) in 1807. From 1809 to 1828, he was the Secretary at War, managing the army's money. He first joined the Cabinet in 1827. This was when George Canning became prime minister.

In 1852, Lord Aberdeen formed a new government. Palmerston became Home Secretary. As Home Secretary, he made many social improvements. When Aberdeen's government failed in 1855, Palmerston became prime minister. He served two terms: 1855–1858 and 1859–1865. He died at 80 years old, shortly after winning another election. He is the last British prime minister to die while still in office.

Palmerston was very good at influencing public opinion. He encouraged British nationalism. Even though Queen Victoria and many political leaders didn't fully trust him, the newspapers and the public loved him. They even called him "Pam." Some people thought Palmerston was not good at personal relationships. He also often disagreed with the Queen about how much say she should have in foreign policy.

Historians see Palmerston as one of Britain's greatest foreign secretaries. This is because he handled big problems well. He believed in the balance of power, which gave Britain a strong role in many conflicts. He was also very good at analyzing situations and always put British interests first. His actions in India, China, Italy, Belgium, and Spain helped Britain for a long time. However, some of his actions, like during the Opium Wars, were criticized by others, such as William Ewart Gladstone.

Contents

- Becoming a Leader: Palmerston's Early Life

- Starting a Political Career

- In Opposition and Changing Parties

- Foreign Secretary: Shaping Britain's Role in the World

- Family Life

- Out of Office and Back Again

- Home Secretary: 1852–1855

- Prime Minister: Leading Britain

- Death and Legacy

- Images for kids

- Places Named After Palmerston

- Palmerston's First Government (Cabinet)

- Palmerston's Second Government (Cabinet)

- Coat of Arms

- See Also

Becoming a Leader: Palmerston's Early Life

Growing Up in England and Ireland

Henry John Temple was born in Westminster, England, on October 20, 1784. His family's title came from Ireland, but he rarely visited there. His father was the 2nd Viscount Palmerston. His mother was Mary Mee, whose father was a London merchant. From 1792 to 1794, he traveled with his family across Europe. In Italy, he learned to speak and write Italian very well. His family also owned a large country estate in County Sligo, Ireland.

He went to Harrow School from 1795 to 1800. At school, Temple was known for standing up to bullies. In 1799, his father took him to the House of Commons. There, young Palmerston met the prime minister, William Pitt.

University Days and Early Interests

Temple then studied at the University of Edinburgh from 1800 to 1803. He learned about economics from Dugald Stewart. Stewart was a friend of famous Scottish thinkers like Adam Smith. Temple later said his time in Edinburgh gave him "whatever useful knowledge and habits of mind I possess." His teachers and friends described him as well-mannered and charming.

Henry Temple became Viscount Palmerston on April 17, 1802, before he turned 18. He also inherited a huge estate in Ireland. He later built Classiebawn Castle there. Palmerston then went to St John's College, Cambridge from 1803 to 1806. Even though he could get his degree without exams as a nobleman, he wanted to earn it through tests. He got top honors in the college exams.

When war was declared against France in 1803, Palmerston joined the Volunteers. This group was formed to fight a possible French invasion. He became a Lieutenant-Colonel Commander in the Romsey Volunteers.

Starting a Political Career

First Steps in Parliament

In February 1806, Palmerston tried to get elected for the University of Cambridge. He lost that election. In November, he was elected for Horsham. But he lost that seat in January 1807 after a vote in the House of Commons.

Thanks to the help of Lord Chichester and Lord Malmesbury, Palmerston got a job as a Junior Lord of the Admiralty. He tried again for the Cambridge seat in May 1807 but lost by three votes.

Palmerston finally entered Parliament in June 1807. He became a Tory MP for Newport on the Isle of Wight. This was a "pocket borough," meaning a powerful person could easily control who got elected there.

On February 3, 1808, he spoke in Parliament. He supported keeping diplomatic talks secret. He also supported the British Navy's attack on Copenhagen in 1807. Denmark was neutral, but Napoleon planned to use the Danish navy against Britain. So, Britain acted first.

Secretary at War: Managing the Army's Money

Palmerston's speech was so good that Spencer Perceval, who formed a government in 1809, offered him a higher job. But Palmerston chose to be Secretary at War. This job was mainly about handling the army's money. He stayed in this role for 20 years. For most of this time, he was not part of the main Cabinet.

In 1818, a retired officer shot Palmerston. The bullet only grazed his back, and he was not seriously hurt. Palmerston even paid for the officer's legal defense after learning he was mentally ill. The officer was then sent to a hospital.

After 1822, the Tory government started to split. A more liberal group, including George Canning, gained influence. They supported free trade and Catholic emancipation (giving more rights to Catholics). Palmerston, though not in the Cabinet, supported these ideas.

When Lord Liverpool retired in 1827, Canning became prime minister. Palmerston was offered a job as Chancellor of the Exchequer, which he accepted. But this appointment didn't happen due to some issues. Palmerston remained Secretary at War but finally got a seat in the Cabinet. Canning's government lasted only four months because he died.

The Duke of Wellington then formed a government. Palmerston and his allies joined it. However, a disagreement led to Palmerston and his friends resigning. In 1828, after more than 20 years in government, Palmerston found himself out of office.

In 1828, Palmerston spoke in favor of Catholic Emancipation. He felt it was wrong to help other groups while Catholics suffered. He also supported the Reform Bill, which aimed to give more men the right to vote. He was seen as a "good Whig at heart" even though he was a Tory. The Catholic Emancipation Act passed in 1829. The Great Reform Act passed in 1832.

In Opposition and Changing Parties

While out of office, Palmerston focused on foreign policy. He had already pushed for Britain to get involved in the Greek War of Independence. He also visited Paris and correctly predicted that the French monarchy would soon be overthrown. In 1829, he gave his first big speech on foreign affairs.

In September 1830, the Duke of Wellington tried to get Palmerston to rejoin the government. But Palmerston refused unless two important Whigs, Lord Lansdowne and Lord Grey, also joined. This moment marked his shift from the Tory party to the Whigs.

Foreign Secretary: Shaping Britain's Role in the World

A Powerful Role in Diplomacy

Palmerston became the Foreign Secretary with great energy. He held this important job for many years: 1830–1834, 1835–1841, and 1846–1851. He was basically in charge of all British foreign policy from 1830 until 1851. His direct and sometimes harsh way of dealing with other countries earned him the nickname "Lord Pumice Stone." His approach to foreign governments was sometimes called "gunboat diplomacy," meaning he was ready to use naval power to get his way.

European Changes in the 1830s

The Revolutions of 1830 shook up Europe. The United Kingdom of the Netherlands split into two countries, creating Belgium. Portugal was in a civil war. In Spain, a young princess was about to become queen. Poland was fighting against the Russian Empire. Meanwhile, Russia, Prussia, and Austria formed a strong alliance.

Palmerston's main goal was to protect British interests and keep peace in Europe. He wanted to maintain the existing balance of power. He didn't have problems with Russia, and while he felt for the Polish people, he didn't intervene in their fight. With problems in Belgium, Italy, Greece, and Portugal, he wanted to calm things down, not make them worse. He focused on peacefully solving the crisis in Belgium.

Belgium's Independence

William I of the Netherlands asked the powerful European countries to help him keep his rights. The London Conference of 1830 was held to discuss this. Britain's idea was for Belgium to become independent. Palmerston believed this would make Britain safer.

Britain worked closely with France. But they also wanted to make sure Belgium stayed independent and didn't become too close to France. If other countries tried to force William I back, France and Britain would stand together. If France tried to take over Belgium, it would lose Britain's support. In the end, Britain's plan worked. Peace was kept, and Prince Leopold became the King of Belgium. This conference was very successful because it helped keep peace in Europe.

Later, even after a Dutch invasion and French counter-invasion in 1831, France and Britain created a treaty for Belgium and Holland. Palmerston's influence grew, and he finally settled relations between Belgium and Holland with a treaty in 1838-39.

Alliances in Southern Europe

In 1833 and 1834, young Queens Isabella II of Spain and Maria II of Portugal represented the new, more liberal governments in their countries. They faced challenges from their relatives who wanted to rule absolutely. Palmerston came up with a plan for an alliance of the liberal countries in Western Europe. A treaty was signed in London in 1834 to bring peace to Spain and Portugal, and it worked.

France was not very keen on this treaty. The French King, Louis Philippe, was even accused of secretly supporting the old rulers. This might have been one reason why Palmerston disliked the French King so much later on. Even though Palmerston wrote in 1834 that Paris was "the pivot of my foreign policy," the differences between Britain and France grew. This led to a constant rivalry that didn't help either country.

Protecting the Ottoman Empire

Palmerston was very interested in Eastern Europe. He had strongly supported Greece's independence. But from 1830, protecting the Ottoman Empire became a key part of his policy. He believed the Ottoman Empire could become strong again. He wrote that talk about its "decay" was "pure unadulterated nonsense."

His two main goals were to stop Russia from gaining control of the Bosporus (a key waterway) and to stop France from gaining control of the Nile in Egypt. He thought that keeping the Ottoman Empire strong was the best way to prevent these things.

Palmerston had long been suspicious of Russia. He disliked its absolute rule and its growing size, which he saw as a threat to the British Empire. He was upset by a treaty between Russia and the Ottomans in 1833.

Despite his public image, he was slow to help the Ottoman Sultan in 1831. The Sultan was being threatened by Muhammad Ali, the ruler of Egypt. Later, after Russia gained power, Palmerston suggested giving aid in 1833 and 1835, but his ideas were rejected by the Cabinet. Palmerston believed that if the Ottoman Empire had ten years of peace, it could become a "respectable Power" again.

However, when Muhammad Ali's power seemed to threaten the Ottoman Empire, Palmerston managed to get the major European powers to agree. In 1839, they signed a note promising to protect the Ottoman Empire's independence. But by 1840, Muhammad Ali had taken over Syria. France, which had closer ties to Muhammad Ali, refused to join in actions against him.

Palmerston was annoyed by France's policy. He signed the London Convention in 1840 with Austria, Russia, and Prussia, without telling the French government. He even threatened to resign if his policy wasn't followed. The European powers then used force. Muhammad Ali's power quickly collapsed. Palmerston's policy was a success, and he became known as one of the most powerful leaders of his time.

In 1838, Palmerston appointed a British consul in Jerusalem. He also supported building an Anglican church there, influenced by Lord Shaftesbury, a Christian Zionist.

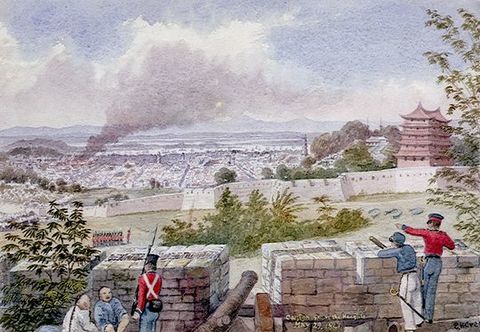

The First Opium War with China

China had strict rules about trade, allowing it only at one port. They also refused official diplomatic relations with most countries. In the 1830s, as Britain ended the East India Company's trade monopoly, both British governments wanted peace and good trade with China. However, the Chinese government refused to change its rules. They stopped British smugglers from bringing opium from India, which was illegal in China.

Britain responded with military force in the First Opium War (1839–1842). Britain won this war. Under the Treaty of Nanjing, China had to pay money and open five treaty ports for world trade. British citizens in these ports also had special rights. Palmerston achieved his goals of equal diplomatic relations and opening China to trade. However, many people criticized him for the immorality of the opium trade.

Palmerston's biographer, Jasper Ridley, explained the government's view. He said conflict was unavoidable between China's old system and Britain's modern, trading nation.

However, humanitarians and reformers in Britain, like William Ewart Gladstone, strongly disagreed. They argued that Palmerston only cared about profits. They said he ignored the terrible effects of opium, which the Chinese government was trying to stop.

Palmerston was also very good at controlling information and public opinion. He leaked secrets to the press and published selected documents to gain more control and publicity. He also stirred up British nationalism.

Family Life

In 1839, Palmerston married Emily Lamb. She was a well-known hostess and the sister of William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, who was prime minister. They did not have any children together. Palmerston lived at Brocket Hall in Hertfordshire, which was his wife's family home. His London home was Cambridge House in Mayfair. He also owned Broadlands in Romsey, Hampshire.

Emily's son-in-law, Lord Shaftesbury, wrote about their marriage. He said Palmerston was always attentive to Lady Palmerston, even when they were old. He described their relationship as a "perpetual courtship."

Historian Gillian Gill said their marriage was a smart political move and also brought them personal happiness. She wrote that Harry and Emily were a perfect match. With a charming, intelligent, and wealthy wife, Palmerston gained the social standing he needed to reach the top of British politics. Lady Palmerston made him happy and was a powerful political helper in her own right. Their marriage was considered one of the best of the century.

Out of Office and Back Again

Opposition: 1841–1846

Within a few months, Palmerston's government ended in 1841. He remained out of office for five years. During this time, Lord Aberdeen became Foreign Secretary. Aberdeen worked to improve relations with France, which Palmerston had strained. Palmerston believed war with France was unavoidable. But Aberdeen and the new French minister, François Guizot, managed to restore friendly relations.

During Sir Robert Peel's government, Palmerston mostly stayed out of the public eye. However, he strongly criticized the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842 with the United States. This treaty settled several border disputes between Canada and the U.S. Even though he criticized it, the treaty successfully resolved issues Palmerston had been concerned about.

Palmerston's reputation for interfering in other countries' affairs and his unpopularity with the Queen were well known. In 1845, Lord John Russell tried to form a government, but it failed. This was because Lord Grey refused to join if Palmerston was in charge of foreign affairs. However, a few months later, the Whigs came to power, and Palmerston returned to the Foreign Office in July 1846. Russell defended Palmerston, saying his policies had a "tendency to produce war" but had advanced British interests without a major conflict.

Foreign Secretary: 1846–1851

Palmerston's years as Foreign Secretary from 1846 to 1851 were filled with major changes across Europe. He was even called "the gunpowder minister" by biographer David Brown.

France and Spain

The French government saw Palmerston's return as a sign of renewed conflict. They used a dispatch where he suggested a German prince for the Spanish queen's hand as an excuse to break agreements. Historian David Brown argues that Palmerston aimed to keep the balance of power in Europe, sometimes even working with France.

Irish Famine and Land Policy

As an Anglo-Irish landlord who lived away from his Irish estates, Palmerston evicted 2,000 of his Irish tenants. This happened because they couldn't pay rent during the Great Irish Famine in the late 1840s. He helped pay for starving Irish tenants to move to North America. Palmerston believed that improving Ireland meant removing small landholders and poor cottagers.

Supporting Revolutions Abroad

The European Revolutions of 1848 spread quickly across Europe. They shook almost every royal family except those in Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Spain, and Belgium. Palmerston openly supported the revolutionary groups in other countries. He strongly believed in national self-determination, meaning people should decide their own future. He also supported constitutional freedoms in Europe. However, he was strongly against Irish independence and the Young Ireland movement.

Italian and Hungarian Independence

Palmerston strongly disliked Austria, mainly because it controlled parts of northern Italy. He believed Austria was important for Europe's balance of power, but he deeply sympathized with Italian independence. He supported the Sicilians against the King of Naples and even allowed weapons to be sent to them from Britain. Although he tried to stop the King of Sardinia from attacking Austria, he helped reduce the punishment for Sardinia's defeat.

In Hungary, the 1848 fight for independence from Austria was crushed by Austrian and Russian armies. Palmerston had encouraged this movement but couldn't give it real help. The British government, or at least Palmerston, was viewed with suspicion by almost all European powers. When Lajos Kossuth, the Hungarian leader, visited England in 1851, Palmerston wanted to host him. But the Cabinet stopped him.

Royal Disagreements and Public Opinion

The British royal family and many ministers were very annoyed by Palmerston's actions. He often took important steps without their knowledge, which they didn't approve of. He had almost complete control over the Foreign Office. The Queen and Prince Albert were angry that other European countries blamed them for Palmerston's actions.

When a politician named Disraeli criticized Palmerston's foreign policy, Palmerston gave a five-hour speech defending himself. He said Britain's policy was to be the "champion of justice and right." He also famously declared: "We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow."

Both Russell and the Queen wanted to fire Palmerston. But the Queen was advised against it by Prince Albert, who respected the limits of royal power. Russell didn't fire him because Palmerston was very popular with the public and skilled in a weak Cabinet.

The Don Pacifico Affair

In 1847, the home of Don Pacifico, a British merchant in Greece, was attacked. The Greek police didn't help. Because Don Pacifico was a British subject, the British government got involved. In 1850, Palmerston used this situation to blockade the port of Piraeus in Greece. Russia and France protested this action because Greece was under their joint protection.

After a big debate, the House of Lords criticized Palmerston's policy. But the House of Commons supported him. Palmerston gave a powerful five-hour speech defending his actions. He said that a British subject should always be protected by the British government against injustice. He compared the British Empire's reach to the Roman Empire, where a Roman citizen was safe anywhere. This was his famous "civis romanus sum" ("I am a citizen of Rome") speech. After this speech, Palmerston's popularity was at an all-time high.

Leaving the Foreign Office

Despite his success in the Don Pacifico affair, many of his own colleagues criticized how he handled foreign relations. The Queen wrote to the Prime Minister, expressing her unhappiness that Palmerston often didn't tell her about his plans. Palmerston accepted this criticism.

On December 2, 1851, Louis Napoleon (who was President of France) took control of the government by force. Palmerston privately congratulated Napoleon. However, the British Cabinet decided Britain must stay neutral. Palmerston resigned, partly because he had sent a message without showing the Queen. Palmerston still had strong support from the press and the public. His popularity grew even more in the 1850s and 1860s.

Home Secretary: 1852–1855

After a short period of Conservative rule, Lord Aberdeen became Prime Minister in 1852. He formed a government with Whigs and Peelites. They felt they couldn't form a government without Palmerston. So, he became Home Secretary in December 1852. Many people thought this was a strange choice because Palmerston was known for foreign affairs.

Social Improvements

As Home Secretary, Palmerston helped pass the Factory Act of 1853. This law closed loopholes in older laws and stopped young people from working between 6 PM and 6 AM. He also tried to pass a law that confirmed workers' rights to form groups, but the House of Lords rejected it. He introduced the Truck Act, which stopped employers from paying workers with goods instead of money. It also prevented employers from forcing workers to buy goods from their own shops.

In August 1853, Palmerston introduced the Smoke Abatement Act. This law aimed to reduce smoke from coal fires, which was a big problem due to the Industrial Revolution. He also oversaw the passage of the Vaccination Act 1853. This law made vaccination compulsory for children for the first time. Palmerston also made it illegal to bury the dead inside churches. He believed this was bad for public health.

Prison Reforms

Palmerston reduced the time prisoners could be held in solitary confinement from 18 months to 9 months. He also ended sending prisoners to Tasmania by passing the Penal Servitude Act of 1853. This law also reduced the maximum sentences for most crimes. Palmerston passed the Reformatory Schools Act of 1854. This law allowed the Home Secretary to send young prisoners to a reformatory school instead of prison. He visited a prison for boys and was impressed by them. He ordered them to be sent to a reformatory school. He also ordered improvements to cell ventilation.

Palmerston strongly disagreed with Lord John Russell's plans to give more working-class people the right to vote. When the Cabinet agreed to Russell's plan in December 1853, Palmerston resigned. However, Aberdeen convinced him to return, saying no final decision had been made. The election reform bill did not pass that year.

The Crimean War

Palmerston was not in charge of foreign policy when the Crimean War (1853–1856) began. One of his biographers believes that if he had been, the war might have been avoided. Palmerston argued that the British Navy should join the French fleet as a warning to Russia. But his idea was rejected.

In May 1853, Russia threatened to invade two areas unless the Ottoman Sultan met their demands. Palmerston pushed for immediate action. He wanted the British Navy sent to help the Turkish navy. He also wanted to tell Russia that Britain would go to war if they invaded. However, Aberdeen disagreed with all of Palmerston's ideas. After many arguments, Aberdeen reluctantly agreed to send a fleet but rejected other proposals. The Russian Emperor, Nicholas I, was annoyed but not stopped. When the British fleet arrived, bad weather forced them to take shelter. Russia saw this as a violation of a treaty and invaded the two areas in July 1853. Palmerston believed this happened because Britain seemed weak.

In the Cabinet, Palmerston argued for a strong war against Russia. But Aberdeen wanted peace. The British public supported the Turks, and Aberdeen became very unpopular. Many people wanted Palmerston to lead.

On March 28, 1854, Britain and France declared war on Russia. The war was slow, with few gains. Public dissatisfaction grew in Britain. Reports of failures, like the mismanagement of the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava, made things worse. The poor health of British soldiers was widely reported by the press. When Parliament voted to investigate the war, Aberdeen resigned as prime minister in January 1855.

Queen Victoria did not trust Palmerston. She first asked Lord Derby to be prime minister. Derby offered Palmerston the job of Secretary of State for War, which he accepted, but only if Clarendon stayed as Foreign Secretary. Clarendon refused, so Palmerston rejected Derby's offer. After other options failed, the Queen asked Palmerston to form a government on February 4, 1855.

Prime Minister: Leading Britain

First Term: 1855–1858

At 70 years old, Palmerston became the oldest person to become Prime Minister for the first time in British history. No Prime Minister since him has been older when first taking office.

Palmerston took a tough stance on the Crimean War. He wanted to expand the fighting, especially in the Baltic Sea, to reduce Russia's threat to Europe. Sweden and Prussia were willing to join, leaving Russia alone. However, France, which had sent more soldiers and suffered more losses, wanted the war to end, as did Austria. In March 1855, the old Tsar died, and his son, Alexander II, wanted peace.

Palmerston found the peace terms too easy on Russia. He convinced Napoleon III of France to stop peace talks until Sevastopol was captured. This would give the allies a stronger position. In September, Sevastopol surrendered, giving the allies control of the Black Sea. Russia then agreed to terms. An armistice was signed in February 1856, and a peace agreement was signed at the Congress of Paris in March 1856. Palmerston's demand for a demilitarized Black Sea was met. In April 1856, Queen Victoria honored Palmerston with the Order of the Garter.

Important Laws and Resignation

After the election, Palmerston passed the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857. This law made it possible for courts to grant divorces for the first time. It also removed divorce cases from church courts. Opponents, including Gladstone, tried to stop the bill by talking for a very long time. But Palmerston was determined and got the bill passed.

In June 1857, news of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 reached Britain. Palmerston sent troops and reinforcements to India. He also agreed to transfer control of India from the East India Company to the British Crown. This was done with the Government of India Act 1858.

After an Italian republican tried to assassinate the French emperor with a bomb made in Britain, the French were very angry. Palmerston introduced a bill to make it a serious crime to plot murder abroad from Britain. The bill failed, and Palmerston was forced to resign in February 1858.

Opposition: 1858–1859

The Conservatives did not have enough votes to form a strong government. In March 1859, Russell introduced a plan to expand voting rights, which the Conservatives opposed but was passed. Parliament was dissolved, and a new election was held, which the Whigs won. Palmerston refused an offer to lead the Conservative party.

On June 6, 1859, the Liberal Party was formed. The Queen asked Lord Granville to form a government. Palmerston agreed to serve under him, but Russell did not. So, on June 12, the Queen asked Palmerston to become prime minister again. Russell and Gladstone agreed to serve under him this time.

Second Term: 1859–1865

Historians often see Palmerston, starting in 1859, as the first Liberal prime minister. In his last term, Palmerston oversaw the passing of important laws. The Offences against the Person Act 1861 updated and organized criminal law. The Companies Act 1862 became the foundation for modern company law.

Foreign policy remained his main strength. He believed he could influence European diplomacy, especially by using France as an ally and trade partner. However, some historians say he often relied more on threats than on decisive action.

Working with Gladstone

Palmerston and William Gladstone were polite to each other, but they disagreed on many things. These included church appointments, foreign affairs, defense, and reforms. Palmerston's biggest challenge in his last term was managing Gladstone, who was his Chancellor of the Exchequer.

A story goes that Gladstone would often come to Cabinet meetings full of new reform ideas. Palmerston would just look at his papers, then tap the table and say, "Now, my Lords and gentlemen, let us go to business." Palmerston told a friend that he thought Gladstone would ruin the Liberal Party.

In 1864, when a bill to expand voting rights was introduced, Palmerston told Gladstone not to commit the government to any specific plan. But Gladstone said in his speech that he didn't see why any man shouldn't have the right to vote unless he was mentally unable. He added that this wouldn't happen unless the working class showed interest in reform. Palmerston believed this encouraged the working class to demand changes.

French involvement in Italy caused fears of an invasion in Britain. Palmerston set up a Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom. This commission recommended building many fortifications to protect British naval bases and ports. Palmerston strongly supported this. Gladstone, however, repeatedly threatened to resign because of the huge cost. Palmerston joked that he received so many resignation letters from Gladstone that he feared they would set fire to the chimney.

The American Civil War

Palmerston's feelings during the American Civil War (1861–65) were with the Confederacy. Even though he was against slavery, he had a lifelong dislike for the United States. He believed that if the U.S. split, it would make Britain more powerful. He also thought the Confederacy would be a good market for British goods.

Britain declared itself neutral at the start of the Civil War in May 1861. The Confederacy was recognized as a fighting party, but not as an independent country. The U.S. Secretary of State, William Seward, threatened to treat any country that recognized the Confederacy as an enemy. Britain relied more on American grain than Confederate cotton. A war with the U.S. would hurt Britain's economy. Palmerston sent more troops to Canada. He was convinced the North would make peace with the South and then invade Canada.

The Trent Affair in November 1861 caused public anger in Britain and a diplomatic crisis. A U.S. Navy ship stopped a British ship, the Trent, and took two Confederate diplomats who were on their way to Europe. Palmerston called this a "gross insult." He demanded the release of the diplomats and sent 3,000 troops to Canada.

The U.S. decided to release the prisoners to avoid war. Palmerston believed that the presence of British troops in Canada convinced the U.S. to give in.

After President Abraham Lincoln announced in September 1862 that he would issue the Emancipation Proclamation, the British Cabinet discussed intervening. They considered it a humanitarian move to stop a possible race war. However, there was also a crisis in France and growing concerns about Russia. The British government had to decide which was more urgent. They decided to focus on threats closer to home and refused France's idea of a joint intervention in America. The feared race war over slavery never happened. Palmerston rejected all further attempts by the Confederacy to gain British recognition.

The raiding ship CSS Alabama, built in Britain, caused another problem for Palmerston. In July 1862, he was advised to stop Alabama because its construction broke Britain's neutrality. Palmerston ordered it detained, but the ship had already left port. Alabama and other ships built in Britain captured or destroyed many Union merchant ships. The U.S. accused Britain of helping build these ships. This led to the postwar Alabama claims for damages against Britain, which Palmerston refused to pay. After his death, Gladstone agreed to pay $15,500,000 in damages.

The Danish Question

The Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck wanted to take over the Danish region of Schleswig and the German region of Holstein. He wanted the port of Kiel. He had an alliance with Austria for this purpose. In a speech in July 1863, Palmerston said Britain, France, and Russia wanted Denmark's independence to be protected. He warned that anyone trying to overthrow Denmark's rights would face more than just Denmark. Palmerston's view was based on the old belief that France was the biggest threat, and Austria and Prussia were weaker. However, France and Britain disagreed on Poland, so France wouldn't work with Britain on the Danish crisis. British public opinion strongly supported Denmark. But Queen Victoria was very pro-German and strongly advised against threatening war. Palmerston himself favored Denmark but also didn't want Britain to get involved militarily.

For five months, Bismarck did nothing. But in November, Denmark adopted a new constitution that tied Schleswig closer to Denmark. By the end of the year, Prussian and Austrian armies had occupied Holstein and were gathering at the border with Schleswig. On February 1, 1864, the Prussian-Austrian armies invaded Schleswig. Ten days later, Denmark asked Britain for help. Russell urged Palmerston to send a fleet to Copenhagen and convince Napoleon III to mobilize French soldiers.

Palmerston replied that the fleet couldn't do much in Copenhagen. He also said nothing should be done to make Napoleon cross the Rhine. Britain had a small army and no strong allies. Bismarck famously said the British Navy lacked wheels, meaning it was useless on land where the war would be fought. In April, Austria's navy was heading to attack Copenhagen. Palmerston told the Austrian ambassador that if his fleet entered the Baltic, it would mean war with Britain. The ambassador replied that the Austrian navy would not enter the Baltic, and it didn't.

Palmerston agreed to Russell's idea of settling the war at a conference. But at the London Conference of 1864 in May and June, the Danes refused to accept losing Schleswig-Holstein. The fighting resumed, and Prussian-Austrian troops quickly took more of Denmark. On June 25, the Cabinet voted against going to war to save Denmark. Russell's idea to send the Royal Navy to defend Copenhagen only passed because of Palmerston's vote. However, Palmerston said the fleet couldn't be sent due to the deep divisions in the Cabinet.

On June 27, Palmerston told the House of Commons that Britain would not go to war with the German powers unless Denmark's existence as an independent country was at risk or its capital was threatened. Conservatives accused Palmerston of betraying the Danes. A vote of no confidence in the House of Lords passed. In the Commons debate, a Conservative MP said Palmerston's words were "idle threats" that foreign powers laughed at. Palmerston replied, "England stands as high as she ever did."

The vote of no confidence in the Commons failed, with Palmerston's old pacifist enemies, Cobden and Bright, voting for him. Palmerston was thrilled. Historians say Palmerston failed to understand Bismarck and the changing world. He still saw Prussia as weak. But Bismarck quietly took the two regions for Prussia.

Final Election and Last Weeks

Palmerston won another general election in July 1865, increasing his majority. His leadership was a big reason for the Liberal Party's success. He then had to deal with the start of Fenian violence in Ireland. Palmerston ordered the Viceroy of Ireland to take action, including possibly suspending trial by jury and watching Americans traveling to Ireland. He believed the Fenian unrest was caused by America.

He advised sending more weapons to Canada and more troops to Ireland. In his last few weeks, Palmerston thought about foreign affairs. He considered a new friendship with France as a "preliminary defensive alliance" against the United States. He also looked forward to Prussia becoming more powerful to balance against the growing threat from Russia. He warned Russell that Russia "will in due time become a power almost as great as the old Roman Empire." He added that "Germany ought to be strong in order to resist Russian aggression."

Death and Legacy

Palmerston was very healthy in his old age. On October 12, 1865, he caught a chill. He then had a high fever, but his condition improved for a few days. However, on the night of October 17, his health worsened. He died at 10:45 AM on October 18, 1865, two days before his 81st birthday.

Palmerston wanted to be buried at Romsey Abbey. But the Cabinet insisted he have a state funeral and be buried at Westminster Abbey. He was buried there on October 27, 1865. He was only the fifth person not of royal blood to receive a state funeral.

Queen Victoria wrote that she regretted his death but had never truly liked or respected him. Florence Nightingale felt differently. She said he would be a great loss. She noted that even though he sometimes joked about doing the right thing, he always did it. She felt she would lose a powerful protector.

Since he had no male heir, his Irish title ended when he died. His property went to his stepson, William Cowper-Temple. This included a large estate in Ireland, where Palmerston had started building Classiebawn Castle.

What People Remember About Palmerston

Palmerston is known as "the defining political personality of his age." He was seen as the perfect example of British nationalism.

Historian Norman Gash described Palmerston as a professional politician. He was smart, sometimes cynical, and tough. He was quick to use opportunities and knew when to give up on a lost cause or wait for a better time. He liked power, enjoyed his job, and worked hard. Later in life, he enjoyed politics more and became a very successful prime minister. He became a legend in his own time, representing a certain kind of England.

Historian Algernon Cecil said Palmerston trusted the press, which he learned to control. He also learned to manage Parliament better than anyone. He knew how to connect with the country's mood. He used his influence in every negotiation with a patriotic boldness that has never been matched.

Palmerston is traditionally seen as "a Conservative at home and a Liberal abroad." He believed the British constitution, established in 1688, was the best. He supported the rule of law and opposed further democracy after the 1832 Reform Act. He wanted to see this liberal system, a mix of monarchy and democracy, replace the absolute monarchies in Europe. More recently, some historians have seen his domestic policies as progressive for his time.

Palmerston is mainly remembered for his foreign affairs. His main goal was to advance British national interests. He is famous for his patriotism. Lord John Russell said that "his heart always beat for the honour of England." Palmerston believed it was good for Britain if liberal governments were set up in Europe. He also used risky tactics, sometimes threatening war to achieve Britain's goals.

In 1886, when Lord Rosebery became Foreign Secretary, John Bright, a critic of Palmerston, asked if he had read about Palmerston's policies. Rosebery said yes. Bright replied, "Then you know what to avoid. Do the exact opposite of what he did. His administration at the Foreign Office was one long crime."

In contrast, the Marquess of Lorne, Queen Victoria's son-in-law, said in 1866: "He loved his country and his country loved him. He lived for her honour, and she will cherish his memory."

In 1889, Gladstone shared a story. A Frenchman complimented Palmerston by saying, "If I were not a Frenchman, I should wish to be an Englishman." Palmerston calmly replied, "If I were not an Englishman, I should wish to be an Englishman." When Winston Churchill pushed for rearmament in the 1930s, he was compared to Palmerston for warning the nation to strengthen its defenses.

Palmerston was also a strong opponent of the slave trade. His efforts to end it were a consistent part of his foreign policy. His stance caused tension with South American countries and the United States. He insisted that the British Navy had the right to search any ship suspected of being involved in the Atlantic slave trade.

Historian A. J. P. Taylor summarized Palmerston's career by pointing out its contradictions. He was a junior minister for 20 years in a Tory government but became a successful Whig Foreign Secretary. Though always a Conservative, he led the shift from Whiggism to Liberalism. He showed British strength but was forced out of office for being too friendly with a foreign ruler. He talked about the Balance of Power but helped start a policy of Britain withdrawing from Europe. He was seen as irresponsible and light-hearted but became a hero to the serious middle-class voters. He reached high office through family connections and kept it by skillfully using the press.

Palmerston is also remembered for his light-hearted approach to government. He once famously said that only three people ever understood the complicated problem of Schleswig-Holstein: one was Prince Albert, who was dead; the second was a German professor, who had gone insane; and the third was himself, who had forgotten it.

Images for kids

Places Named After Palmerston

- The town of Palmerston in Canada was named after him in 1875.

- The former township of Palmerston in Frontenac County, Canada.

- In New Zealand, the town of Palmerston and the city of Palmerston North.

- The Australian city of Darwin was once named Palmerston. A new city called Palmerston was built next to Darwin in 1971.

- Palmerston Atoll in the Cook Islands is named after him.

- In Dublin, Ireland, Palmerston Road and Temple Road are named after him.

- Palmerston Forts are a series of forts built in Britain.

- Several places in Portsmouth, England, are named after Palmerston, including Palmerston Road in Southsea.

- Palmerston Road in East Sheen, London.

- Palmerston Place in West End, Edinburgh, Scotland.

- Palmerston Road in Walthamstow, London, and The Lord Palmerston Pub.

- The Lord Palmerston public house in Dartmouth Park, London.

- Palmerston Park and the Palmerston Hotel in Tiverton, Devon, his constituency.

- Palmerston Park, Southampton, and Palmerston Road nearby. A statue of him was put in the park in 1869.

- Temple Street in Sligo, Ireland.

- Palmerston Street in Derby, England.

- Palmerston Street in Bedford, England.

- Palmerston Road and Palmerston Park in east Belfast, Northern Ireland.

- Palmerston Boulevard and Palmerston Avenue in Toronto, Canada.

- Palmerston Street in Romsey, Hampshire, where there is also a statue of him.

Palmerston's First Government (Cabinet)

(February 1855 – February 1858)

- Lord Palmerston – First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Commons

- Lord Cranworth – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Granville – Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords

- The Duke of Argyll – Lord Privy Seal

- Sir George Grey – Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Clarendon – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Sidney Herbert – Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Lord Panmure – Secretary of State for War

- Sir James Graham – First Lord of the Admiralty

- William Ewart Gladstone – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Sir Charles Wood – President of the Board of Control

- Lord Stanley of Alderley – President of the Board of Trade

- Lord Harrowby – Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Sir William Molesworth, 8th Baronet – First Commissioner of Works

- Lord Canning – Postmaster-General

- Lord Lansdowne – Minister without a specific department

Palmerston's Second Government (Cabinet)

(June 1859 – October 1865)

- Lord Palmerston – First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Commons

- Lord Campbell – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Granville – Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords

- The Duke of Argyll – Lord Privy Seal

- Sir George Cornewall Lewis – Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord John Russell – Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- The Duke of Newcastle – Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Sidney Herbert – Secretary of State for War

- Sir Charles Wood – Secretary of State for India

- The Duke of Somerset – First Lord of the Admiralty

- William Ewart Gladstone – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Edward Cardwell – Chief Secretary for Ireland

- Thomas Milner Gibson – President of the Board of Trade and of the Poor Law Board

- Sir George Grey – Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Lord Elgin – Postmaster-General

Coat of Arms

|

See Also

In Spanish: Lord Palmerston para niños

In Spanish: Lord Palmerston para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |