Trent Affair facts for kids

The Trent Affair was a big problem in 1861 during the American Civil War. It almost caused a war between the United States and Great Britain. The U.S. Navy stopped a British ship and took two important leaders from the Confederacy. The British government was very angry. To avoid war, the U.S. government decided to let the Confederate leaders go.

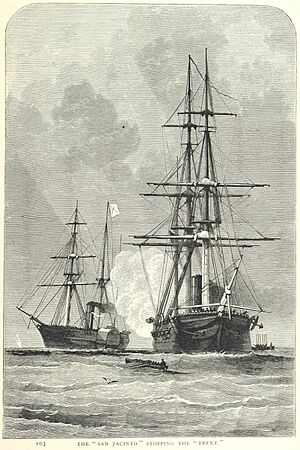

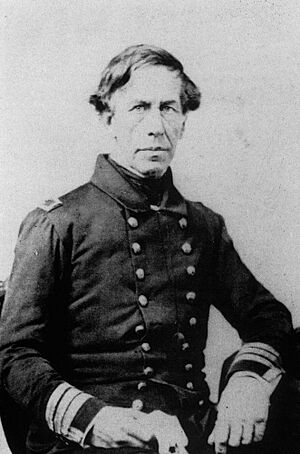

On November 8, 1861, a U.S. Navy ship called USS San Jacinto stopped the British mail ship RMS Trent. Captain Charles Wilkes of the Union Navy was in charge. He took two Confederate diplomats, James Murray Mason and John Slidell, off the ship. These men were on their way to Britain and France. They wanted to get other countries to recognize the Confederacy as a new nation. They also hoped to get money and military help.

People in the United States were very happy about the capture. They cheered Captain Wilkes and were ready to fight Britain. In the Confederate states, people hoped this event would cause a big fight between Britain and the U.S. They thought it might even lead to war or at least get Britain to recognize their country. Confederates knew their future depended on Britain and France helping them. In Britain, people were very upset. They felt their rights as a neutral country had been ignored. They also felt their national honor was insulted. The British government demanded an apology and that the prisoners be released. They also started getting their military ready in British North America (Canada) and the Atlantic Ocean.

President Abraham Lincoln and his main advisors did not want to risk a war with Britain. After a few tense weeks, the problem was solved. The Lincoln government released the Confederate diplomats. They also said that Captain Wilkes had acted on his own, without orders. However, they did not give a formal apology. Mason and Slidell then continued their trip to Europe.

Contents

Why the Trent Affair Happened

Relations between the United States and Britain were often difficult. They almost went to war when Britain seemed to support the Confederacy. This was in the early part of the American Civil War. British leaders were often annoyed by what they saw as Washington's actions. These tensions became very strong during the Trent affair.

The Confederacy and its president, Jefferson Davis, believed something important. They thought Europe needed Southern cotton for its factories. They hoped this need would make Europe recognize their country. They also hoped Europe would step in to help end the war.

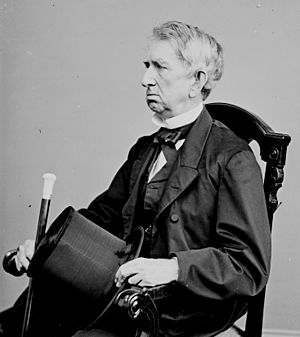

The Union's main goal in foreign affairs was the opposite. They wanted to stop Britain from recognizing the Confederacy. Many past problems between the U.S. and Britain had been solved. Relations had gotten better in the 1850s. William H. Seward, the U.S. Secretary of State, guided American foreign policy. He wanted to keep the U.S. out of other countries' business. He also wanted to stop other countries from getting involved in American affairs.

British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston wanted Britain to stay neutral. His main worries were in Europe. Napoleon III had big plans in Europe. Also, Otto von Bismarck was becoming powerful in Prussia. During the Civil War, Britain's actions were shaped by its past policies. They also considered their own national interests, both military and economic.

As a strong naval power, Britain always said that neutral countries must respect its blockades. From the start of the war, Britain avoided actions that might challenge the Union blockade. From the South's view, Britain's policy helped the Union blockade. This made Confederates very frustrated.

The Russian Minister in Washington, Eduard de Stoeckl, noticed something. He said, "The Cabinet of London is watching attentively the internal disagreements of the Union." He thought Britain was waiting to see the outcome. Cassius Clay, the U.S. minister in Russia, also saw Britain's feelings. He said, "They hoped for our ruin! They are jealous of our power."

At the start of the Civil War, Charles Francis Adams, Sr. was the U.S. minister to Britain. He made it clear that Washington saw the war as an internal problem. They believed the Confederacy had no rights under international law. Any move by Britain to recognize the Confederacy would be seen as an unfriendly act. Seward told Adams to warn Britain. He said a country with many scattered lands, like Britain, should be careful. They should not "set a dangerous precedent" by supporting rebels.

Lord Lyons, a skilled diplomat, was the British minister to the U.S. Even though he didn't trust Seward, Lyons kept a "calm and measured" approach. This helped solve the Trent crisis peacefully.

Confederate Diplomats and British Neutrality

The Trent affair became a big problem in late November 1861. But the first steps happened much earlier. In February 1861, the Confederacy sent three people to Europe. Their names were William Lowndes Yancey, Pierre Rost, and Ambrose Dudley Mann. Their job was to explain the South's goals to European governments. They wanted to start diplomatic relations and make trade agreements.

British leaders generally thought the U.S. would split up. They remembered their own failed attempt to keep their American colonies. So, they thought the Union's fight to keep the country together was unreasonable. But they also knew they had to deal with it. The British thought ending the war quickly would be a good thing for everyone. Lord Russell, the Foreign Secretary, told Lyons to help settle the war.

The Confederate diplomats met with Russell on May 3. News of the Battle of Fort Sumter had just reached London. But they didn't talk about open warfare. Instead, the envoys stressed that their new nation wanted peace. They argued that leaving the Union was legal. Their strongest point was how important cotton was to Europe. Russell asked about slavery, but the envoys said reopening the slave trade was not their plan. Russell didn't commit to anything.

On May 13, 1861, Queen Victoria made an important announcement. She declared Britain neutral in the American Civil War. This meant Britain recognized the South as a "belligerent." This status gave Confederate ships the same rights as U.S. ships in foreign ports. Confederate ships could get fuel and repairs. But they could not get military weapons. This allowed Confederate ships to chase Union ships around the world. France, Spain, and other countries also declared neutrality.

On May 18, Adams met with Russell to protest Britain's neutrality. Adams argued that Britain recognized the Confederacy too soon. He said they had not even shown they could fight a war at sea. The U.S. worried that recognizing the South as a belligerent was the first step to recognizing them as a country. Russell said they weren't planning to recognize the Confederacy yet. But he wouldn't rule it out for the future.

Meanwhile, in Washington, Seward was upset. He didn't like the neutrality announcement or Russell meeting with Confederates. Seward told Adams that formal recognition of the Confederacy would make Britain an enemy. President Lincoln reviewed Seward's letter. He made the language softer. He told Adams not to give Russell a copy. Adams was still shocked by the letter. He felt it was almost a threat of war against all of Europe. When Adams met Russell on June 12, Russell said he wouldn't meet with the Confederate mission anymore.

More problems came up later. In August, Seward found out Britain was secretly talking with the Confederacy. Britain wanted the Confederacy to agree to the Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law. This declaration had rules about privateers and blockades. The U.S. had not signed this treaty before. But after the Union blockaded the South, Seward wanted to talk about it again.

Russell had told Lyons to get the Confederacy to agree to the Paris Declaration. Lyons gave this job to Robert Bunch, a British consul. Bunch went too far. He told Confederates that agreeing to the declaration was the "first step to [British] recognition." The Union soon found out about this. A British merchant was arrested in New York. He had a British diplomatic passport from Bunch. He was carrying a diplomatic bag that was searched. It had letters from Bunch about his dealings with the Confederacy.

When asked, Russell admitted his government was trying to get the Confederacy to agree to parts of the treaty. But he denied it was a step towards recognizing them. Seward let this issue go. He did demand Bunch be removed, but Russell refused.

France generally supported Britain's views on the Civil War. Henri Mercier, the French minister, worked with Lyons. For example, they tried to meet Seward together. But Seward insisted on meeting them separately.

Edouard Thouvenel was the French Foreign Minister. He was seen as pro-Union. He helped stop Napoleon III from recognizing the Confederacy. Thouvenel met with Confederate envoy Pierre Rost in June. He told him not to expect diplomatic recognition.

William L. Dayton was the U.S. minister to France. He had no foreign experience. But he was helped by John Bigelow, the U.S. consul general in Paris. Dayton protested to Thouvenel about the recognition of Confederate belligerency. Napoleon offered to help resolve the conflict. Seward told Dayton that if any help was needed, it would be from France.

News of the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run reached Europe. It made the British think Confederate independence was certain. Yancey asked for another meeting with Russell. But he was turned down. Russell said any communication should be in writing. Yancey sent a long letter on August 14. He again explained why the Confederacy should be recognized. Russell replied on August 24. He said Britain still saw the war as an internal matter. British policy would only change if the war ended or if negotiations settled things. No meeting was set. This was the last talk between the British government and the Confederate envoys. When the Trent Affair happened, the Confederacy had no direct way to talk with Britain. They were left out of the negotiations.

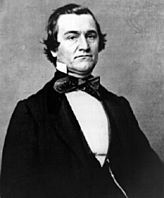

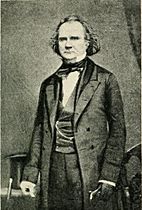

By August 1861, Yancey was tired and ready to quit. President Davis decided he needed new diplomats in Britain and France. He chose John Slidell of Louisiana and James Mason of Virginia. Both men were respected in the South. They also had some experience in foreign affairs.

R. M. T. Hunter was the new Confederate Secretary of State. He told Mason and Slidell to stress the Confederacy's stronger position. It had grown from seven to eleven states. They were to say that an independent Confederacy would help Britain and France. It would also limit the U.S.'s power. They were to compare the Confederacy's fight to Italy's fight for independence. Britain had supported Italy. They also had to argue against the Union blockade.

The Capture of the Trent

The Confederate envoys' travel plans were not a secret. The Union government knew their every move. By October 1, Slidell and Mason were in Charleston, South Carolina. Their first plan was to use a fast ship called CSS Nashville. They wanted to sneak past the Union blockade and sail straight to Britain. But five Union ships guarded the main channel into Charleston. The Nashville was too big for the side channels. They thought about escaping at night. But the tides and strong winds stopped them. They also thought about going through Mexico. But that would take too long.

A smaller ship called Gordon was suggested. It could use the shallow back channels. It was also fast enough to escape Union ships. The Confederacy couldn't afford to buy it. But a local cotton broker, George Trenholm, paid to charter it. The ship was renamed Theodora. It left Charleston at 1 a.m. on October 12. It successfully avoided the Union blockade. On October 14, it reached Nassau in the Bahamas. But they missed a British ship going to St. Thomas. This was the main place for British ships leaving the Caribbean for Britain. They found out British mail ships might be in Spanish Cuba. So, Theodora sailed towards Cuba.

Theodora arrived off Cuba on October 15. Its coal was almost gone. A Spanish warship stopped Theodora. Slidell and George Eustis Jr. went aboard. They learned that British mail ships docked at Havana. But the last one had just left. The next one, the RMS Trent, would arrive in three weeks. Theodora docked in Cárdenas, Cuba on October 16. Mason and Slidell got off. They decided to stay in Cardenas. Then they would travel overland to Havana to catch the next British ship.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government heard rumors. They thought Mason and Slidell had escaped on Nashville. U.S. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles ordered a fast warship to Britain. He wanted it to stop Nashville. On October 15, the Union ship USS James Adger sailed towards Europe. It was ordered to chase Nashville if needed. James Adger reached Britain in early November. The British government knew the U.S. would try to catch the envoys. They thought they were on Nashville. Palmerston ordered a Royal Navy ship to patrol British waters. This was to make sure any capture happened outside British territory. This would avoid a diplomatic problem. When Nashville arrived on November 21, the British were surprised. The envoys were not on board.

The Union ship USS San Jacinto, led by Captain Charles Wilkes, arrived in St. Thomas on October 13. Wilkes learned from a newspaper that Mason and Slidell were leaving Havana on November 7. They would be on the British mail ship RMS Trent. It was going to St. Thomas and then England. He realized the ship would use the "narrow Bahama Channel." This was the only deep-water route between Cuba and the shallow Grand Bahama Bank. Wilkes discussed legal options with his second in command. He decided that Mason and Slidell could be taken as "contraband of war." Historians later said there was no legal reason for this capture.

Wilkes was known for making bold decisions. He was a famous explorer and naval officer. But he also had a reputation for being "stubborn, overzealous, impulsive, and sometimes insubordinate."

Trent left on November 7 as planned. Mason, Slidell, their secretaries, and Slidell's family were on board. Just as Wilkes thought, Trent passed through the Bahama Channel. San Jacinto was waiting there. Around noon on November 8, lookouts on San Jacinto saw Trent. Trent raised the Union Jack flag as it got closer. San Jacinto fired a shot across Trent's bow. Captain James Moir of Trent ignored it. San Jacinto fired a second shot that landed right in front of Trent. Trent stopped.

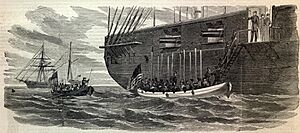

Lieutenant Fairfax boarded Trent from a small boat. Two other boats with twenty armed men followed. Fairfax told his armed men to stay in their boats. He wanted to avoid making the situation worse. Fairfax told Captain Moir he was there "to arrest Mr. Mason and Mr. Slidell and their secretaries." He said he would send them to the U.S. warship. The crew and passengers on Trent threatened Fairfax. The armed men from the cutters then came aboard to protect him. Captain Moir refused to give a passenger list. But Slidell and Mason came forward and identified themselves. Moir also refused to let them search the ship for illegal goods. Fairfax did not force this issue. If he had, he would have had to seize the ship. This could have been seen as an act of war. Mason and Slidell formally refused to go willingly. But they did not fight when Fairfax's crew took them to the cutter.

Wilkes later said he believed Trent was carrying "important dispatches." He thought these papers were harmful to the United States. But no papers were found in the envoys' luggage. Mason's daughter later wrote that a British passenger on Trent had hidden the Confederate dispatch bag. He later gave it to the envoys in London. This was a clear violation of Britain's neutrality.

International law said that if illegal goods were found on a ship, the ship should be taken to a special court. This was Wilkes' first idea. But Fairfax argued against it. Transferring crew from San Jacinto to Trent would leave San Jacinto short-handed. It would also cause problems for Trent's other passengers and mail. Wilkes agreed. Trent was allowed to continue to St. Thomas. The two Confederate envoys and their secretaries were taken off.

San Jacinto arrived in Hampton Roads, Virginia, on November 15. Wilkes sent news of the capture to Washington. He was then ordered to Boston. There, he delivered the captives to Fort Warren, a prison for captured Confederates.

Reactions in America

Most Northerners heard about the Trent capture on November 16. By November 18, newspapers were full of excitement. Mason and Slidell were called "knaves" and "cowards."

Everyone wanted to explain why the capture was legal. The British consul in Boston said every citizen was "walking around with a Law Book." They were all trying to prove Wilkes' right to stop the British mail boat. Many newspapers also said Wilkes' actions were legal. Many lawyers agreed. Harvard law professor Theophilus Parsons said Wilkes had a legal right to take Mason and Slidell. Caleb Cushing, a former Attorney General, agreed. He said Wilkes' act was something any nation would do.

A special dinner was held to honor Wilkes in Boston on November 26. Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew praised Wilkes for his "manly and heroic success." He spoke of the "exultation of the American heart." On December 2, Congress thanked Wilkes. They said he showed "brave, adroit and patriotic conduct." They suggested he get a "gold medal."

But as people looked closer, some had doubts. Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy, approved Wilkes' actions. But he also warned him. He said not taking Trent to a prize court should not be a future example. On November 24, the New York Times said there was no clear example for this. The Albany Evening Journal suggested that if Wilkes acted without orders, the government should apologize. People soon noticed that taking Mason and Slidell was like the British practice of "impressment." The U.S. had always been against this. It had even led to the War of 1812 with Britain. The idea of people being "contraband" didn't seem right to many.

People also started to realize that avoiding a war with Britain was more important than legal arguments. Older leaders like James Buchanan and Thomas Ewing said the envoys should be released. By mid-December, many newspapers started to agree. They prepared Americans for the release of the prisoners. The idea that Wilkes acted without orders spread. People said he was wrong to hold a "prize court" on his ship.

The United States was slow to back down at first. Seward had missed a chance to release the envoys right away. This would have shown America's long-held view of international law. He had written to Adams that Wilkes did not act under instructions. But he waited for Britain's response before saying more. He repeated that recognizing the Confederacy would likely lead to war.

On December 4, Lincoln met with Alexander Tilloch Galt, a Canadian leader. Lincoln told him he didn't want trouble with England or Canada. When asked about the Trent incident, Lincoln said, "Oh, that'll be got along with." Galt sent his report to Lyons, who sent it to Russell. Galt wrote that Lincoln's promises might not be reliable. He felt American policy was too influenced by public feelings. Lincoln's yearly message to Congress didn't directly mention the Trent affair. But he said the U.S. could field a 3,000,000-man army. He stated they could "show the world" they could protect themselves from abroad.

Money also played a part. Salmon P. Chase, the Treasury Secretary, worried about how events might affect American interests in Europe. He knew New York banks planned to stop paying in gold. Chase later argued for releasing the envoys. He wrote in his diary that releasing them was hard. But he said, "we cannot afford delays." He knew the public would be worried. Commerce would suffer. And action against the rebels would be harder. The Trent affair contributed to a financial crisis.

On December 15, the U.S. heard about Britain's reaction. Britain had learned of the events on November 27. Lincoln was with Senator Orville Browning when Seward brought the first newspaper reports. They said Palmerston was demanding the prisoners' release and an apology. Browning thought Britain's war threat was "foolish." He said, "We will fight her to the death." That night, Seward was heard saying, "We will wrap the whole world in flames." The mood in Congress had also changed. On December 16 and 17, they debated the issue. A Democrat named Clement L. Vallandigham wanted the U.S. to keep the seizure. But his idea was voted down. The government waited for Britain's formal response. It arrived in America on December 18.

Britain's Response

When USS James Adger arrived in Southampton, its commander, Marchand, learned his targets were in Cuba. He boasted he would capture the envoys even on a British ship. Because of Marchand's statements, the British Foreign Office asked for legal advice. They wanted to know if it was legal to take the men from a British ship.

On November 12, Palmerston told Adams that Britain would be offended if the envoys were taken from a British ship. Palmerston said seizing the Confederates would be "highly inexpedient." He also said a few more Confederates in Britain would not change policy. Palmerston questioned why Adger was in British waters. Adams said Marchand's orders were only to seize Mason and Slidell from a Confederate ship.

News of the actual capture reached London on November 27. Much of the public and many newspapers saw it as a huge insult. They called it a clear violation of maritime law. The London Chronicle said it was an "act of violence."

The London Standard saw the capture as "one of a series of planned blows." They thought it was meant to start a war with the Northern States. An American visitor wrote to Seward that people were "frantic with rage." He thought 999 out of 1,000 people would want immediate war. A member of Parliament said the British flag should be "torn into shreds" if America didn't fix things. The seizure led to one anti-Union meeting in Liverpool.

The Times newspaper published its first report from the U.S. on December 4. Its reporter, W. H. Russell, wrote about American reactions. He said there was "so much violence of spirit among the lower orders." He thought any apology would be bad for American leaders. Times editor John T. Delane was more moderate. He warned people not to "regard the act in the worst light." He questioned why the U.S. would "force a quarrel upon the Powers of Europe." This calm approach was common in Britain.

The government got its first clear information from Commander Williams. He was a passenger on the Trent. He went straight to London. He spent hours with the Admiralty and the Prime Minister. Political leaders were strongly against the American actions. Lord Clarendon, a former foreign secretary, said Seward was "trying to provoke us into a quarrel."

Palmerston asked legal experts to prepare a report. An emergency cabinet meeting was set for November 29. Palmerston also told the War Office to stop planned budget cuts. Russell met with Adams on November 29. He wanted to know if Adams had any information about American intentions. Adams didn't know Seward had already sent him a letter. That letter said Wilkes acted without orders. So, Adams couldn't give Russell any information to calm the situation.

Palmerston believed Adams had verbally agreed that British ships would not be bothered. He reportedly started the cabinet meeting by throwing his hat on the table. He said, "I don't know whether you are going to stand this, but I'll be damned if I do."

Letters from Lyons were given to everyone. These letters described the excitement in America. They also warned that Seward might cause such an incident. Lyons said it would be hard for the U.S. to admit Wilkes was wrong. He also suggested sending more troops to Canada. Palmerston told Lord Russell that the incident might be a "deliberate and premeditated insult" by Seward. He thought it was designed to "provoke" a fight with Britain.

After several days of talks, Russell sent drafts of letters to Queen Victoria on November 30. These letters were for Lord Lyons to give to Seward. The Queen asked her husband, Prince Albert, to review them. Albert was sick with typhoid fever. But he read the letters. He thought the demands were too aggressive. He wrote a softer version.

The cabinet used Albert's suggestions in its official letter to Seward. This allowed Washington to say Wilkes acted on his own. It also let them deny any intent to insult the British flag. The British still demanded an apology. They also wanted the Confederate diplomats released. Lyons' private instructions told him to give Seward seven days to reply. If the answer wasn't good, he was to close the British Legation and go home. To calm things further, Russell added a private note. He told Lyons to meet Seward and tell him what was in the official letter before delivering it. Lyons was told that if the diplomats were released, Britain would "be rather easy about the apology." He said an explanation through Adams would probably be fine. He repeated that the British would fight if needed. He also suggested that "the best thing would be if Seward could be turned out." The letters were sent on December 1. They reached Washington on December 18.

Military Preparations

While diplomacy was on hold, military preparations sped up. There had been financial unrest in Britain since the Trent news. Stock values fell. The Times noted that financial markets acted as if war was certain.

Early on, there was concern that Napoleon III would use a U.S.-British war to act against British interests. France and Britain had disagreements in other parts of the world. Palmerston saw France building up coal supplies in the West Indies. He thought France was getting ready for war with Britain. The French Navy was smaller. But it had shown itself equal to the Royal Navy in the Crimean War. A possible buildup of ironclad ships by France would threaten Britain.

France quickly eased Britain's worries. On November 28, Napoleon met with his cabinet. They had no doubt the U.S. actions were illegal. They agreed to support whatever Britain demanded. Thouvenel told Britain of their decision. After learning Britain's demands, Thouvenel approved them. On December 4, instructions were sent to Mercier to support Lyons.

A small stir happened when General Winfield Scott and Thurlow Weed arrived in Paris. Scott was the former commander of all Union troops. Weed was close to Seward. Their mission was to counter Confederate propaganda. The timing seemed strange to the British. Rumors spread that Scott was blaming Seward for the incident. Scott ended the rumors with a letter on December 4. It was published in Paris and reprinted in London. Scott denied the rumors. He said the U.S. government wanted to keep Britain's friendship.

John Bright and Richard Cobden also argued for the United States. They were strong supporters of the U.S. in Britain. Both had doubts about Wilkes' actions. But they argued that the U.S. had no plans to attack Britain. Bright publicly said the confrontation was not planned by Washington. He questioned why Britain was preparing for war. Cobden also spoke at public meetings and wrote letters. As time passed, more voices spoke against war. The Cabinet also started thinking about other options, like arbitration.

Even before the Civil War, Britain needed a military plan for the divided U.S. In 1860, Rear Admiral Sir Alexander Milne commanded the Royal Navy in North America. His orders were to avoid actions that might offend any U.S. party. He was told not to show favoritism. Milne avoided American ports. This was a long-standing Royal Navy policy to prevent desertion. In May 1861, the Neutrality Proclamation was issued. This increased British worry about Confederate privateers and Union blockading ships. Milne was reinforced. On June 1, British ports were closed to any captured ships. This helped the Union. Milne watched the Union blockade. But he never tried to challenge it.

Milne received a letter from Lyons on June 14. Lyons said a sudden war with the U.S. was possible. Milne warned his forces. He asked for more reinforcements. He also said defenses in the West Indies were weak. He reported that forts were in bad shape. Guns were unusable. There were no supplies or ammunition. Milne said his forces were busy protecting trade. He had only one ship for special needs.

The Duke of Somerset, the head of the Admiralty, was against reinforcing Milne. He thought the existing steam-powered fleet was better than the Union's mostly sail ships. He didn't want to spend more money. Britain was building new iron ships. Because of this, historian Kenneth Bourne said Britain was not ready for war.

Land Forces

In March 1861, Britain had 2,100 troops in Nova Scotia. They had 2,200 in the rest of Canada. They also had scattered posts elsewhere. Lieutenant General Sir William Fenwick Williams was the commander in North America. He wrote to Britain many times. He said he needed many more troops to defend Canada.

Some troops were sent in May and June. Palmerston wanted to increase troops in Canada to 10,000. But he faced resistance. Sir George Cornwall Lewis, head of the War Office, questioned the threat. He thought it was "incredible" that the U.S. would start a war with Britain. In Parliament, there was general opposition to sending more troops. This was due to political, military, and economic reasons. A long-standing issue was Parliament wanting Canada to pay more for its own defense.

British leaders knew that a military option was important. The First Lord of the Admiralty believed Canada could not be defended from a serious U.S. attack. It would be hard and costly to win it back. Somerset suggested a naval war instead of a ground war.

Military preparations started quickly after the Trent news. Secretary of War Sir George Lewis proposed sending "thirty thousand rifles, an artillery battery, and some officers to Canada." He wrote to Palmerston on December 3. He planned to send one regiment and one artillery battery the next week. Three more regiments and more artillery would follow. Because of winter, troops would land in Nova Scotia. The Saint Lawrence River freezes in December.

Russell worried that Lewis and Palmerston might act too soon. This could ruin chances for peace. So, he asked for a small committee to help with war plans. The group was created on December 9. Its first job was Canadian defense. They used old plans and new information from experts.

Canada had 5,000 regular troops and about 5,000 "ill-trained" militia. Only one-fifth of the militia were organized. In December, Britain sent 11,000 troops on 18 ships. By the end of the month, they were ready to send 28,400 more men. By the end of December, the crisis ended. But reinforcements had raised the troop count to 17,658 men. This was against an expected American invasion of 50,000 to 200,000 troops.

In Canada, General Williams visited forts in November and December. Historian Gordon Warren wrote that Williams found "forts were either decaying or nonexistent." He said the amount of work needed was huge. To defend Canada, Britain thought they needed 10,000 regular troops. They also needed 100,000 auxiliary troops. These would form garrisons and harass the enemy. Canada had two sources for these troops. One was the Sedentary Militia. This included all Canadian males aged 16 to 60. The other was volunteer groups.

Williams' task was like what the Union and Confederates faced a year earlier. In Canada, there were 25,000 weapons. 10,000 of them were old smoothbore guns. In the Maritimes, there were 13,000 rifles and 7,500 smoothbores. Weapons were available in England. But getting them to Canada was hard. 30,000 Enfield rifles were sent on December 6. By February 10, 1862, the Times reported that modern weapons for 105,550 men had arrived in Canada.

On December 2, the Canadian government agreed to increase its volunteer force to 7,500. The risk of war pushed volunteers to 13,390 by May 1862. On December 20, Williams also started training one company of 75 men from each militia battalion. This was about 38,000 men. He planned to raise this to 100,000.

By summer 1862, after the crisis, Canadian volunteers numbered 16,000. The militia returns for 1862 showed 470,000 militiamen in Canada. But they didn't expect to raise more than 100,000 for active service. Canada was not ready for war with the United States. In the War Cabinet, there was disagreement. Some thought the Union would stop its war and attack Canada. Others thought the war would continue. Both agreed Canada would face a major ground attack. They knew it would be hard to stop. Defense depended on "extensive fortifications" and "seizing command of the lakes." But the fortification plans had never been built. On the Great Lakes, neither Canada nor the U.S. had many naval ships in November. Britain would be vulnerable there until spring 1862.

Invasion Plans

To counter their weaknesses, a British invasion of the United States from Canada was suggested. They hoped a successful invasion would take large parts of Maine, including Portland. The British believed this would make the U.S. move troops away from Canada. Burgoyne, Seaton, and MacDougall supported the plan. Lewis recommended it to Palmerston on December 3. No preparations for this attack were ever made. Success depended on attacking at the very start of a war. MacDougall believed a "strong party" in Maine wanted to join Canada. He thought this party would help a British invasion.

On December 28, 1861, Governor James Douglas of British Columbia wrote to Henry Pelham-Clinton, 5th Duke of Newcastle. He argued that Britain should take parts of the U.S.-held Pacific Northwest. This was while America was busy with the Civil War.

At sea, Britain had its greatest strength. They could bring the war to the United States if needed. The Admiralty told Russell on December 1 that Milne should focus on protecting trade. This was trade between America, the West Indies, and England. Somerset gave orders to British naval units worldwide. They were to be ready to attack American shipping. The Cabinet also agreed that a strong blockade was key to British success.

The British strongly believed they had better naval power than the Union. Union ships outnumbered Milne's forces. But many U.S. ships were just converted merchant ships. The British had more total guns. Bourne suggested this advantage could change as both sides built more ironclads. British ironclads needed deeper water. They couldn't operate in American coastal waters. This left wooden ships vulnerable to Union ironclads.

Luckily, the military option was not needed. If it had been, Warren concluded that "Britain's world dominance... had vanished." He said the Royal Navy, though powerful, "no longer ruled the waves."

Some people at the time were less confident about the U.S. Navy. On July 5, 1861, Lieutenant David Dixon Porter wrote to a friend. He said a small English ship with one Armstrong gun could defeat the largest U.S. Navy ship. He noted the Armstrong gun's range was 1.5 miles. He said none of the U.S. guns could reach that far.

How the Crisis Ended

On December 17, Adams received Seward's message. It said Wilkes acted without orders. Adams immediately told Russell. Russell was encouraged but waited for a formal response. The news was not made public. But rumors of the Union's intentions spread. Russell refused to confirm the information. John Bright later asked in Parliament why the message wasn't published.

In Washington, Lyons received the official British response on December 18. As instructed, Lyons met with Seward on December 19. He described the British demands without giving the official papers. Seward was told Britain expected a reply within seven days. At Seward's request, Lyons gave him an unofficial copy. Seward immediately shared it with Lincoln. On December 21, Lyons visited Seward to deliver the "British ultimatum." But after more talk, they agreed to delay the formal delivery for two days. Lyons and Seward agreed the seven-day deadline was not part of the official message.

Senator Charles Sumner was head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He often advised President Lincoln on foreign affairs. Sumner immediately knew the U.S. had to release Mason and Slidell. But he stayed quiet during the excitement. Sumner had traveled in England. He regularly wrote to many British political activists. In December, he got alarming letters from Richard Cobden and John Bright. They talked about Britain preparing for war. They also shared their doubts about Wilkes' actions. The Duchess of Argyll, a strong anti-slavery supporter, wrote to Sumner. She said the capture was "the maddest act that ever was done."

Sumner took these letters to Lincoln. Lincoln had just learned of the official British demand. Sumner and Lincoln met daily for the next week. They discussed what a war with Britain would mean. On December 24, Sumner wrote that they worried about the British fleet. It could break the blockade and start its own. They also worried about France recognizing the Confederacy. And they feared smuggling of British goods through the South. This would hurt American manufacturing. Lincoln thought he could meet Lyons directly. He believed he could "show him in five minutes that I am heartily for peace." But Sumner convinced him that such a meeting was not proper. Both men agreed that arbitration might be the best solution. Sumner was invited to a cabinet meeting on Christmas morning.

Information from Europe kept flowing to Washington. On December 25, a letter from Adams, written on December 6, arrived. Two messages from American consuls in Britain also arrived. From Manchester, the news was that Britain was arming "with the greatest energy." From London, the message was that a "strong fleet" was being built. Work was going on day and night. Thurlow Weed, who had moved to London, also sent a letter. He told Seward that "such prompt and gigantic preparations were never known."

The disruption of trade threatened the Union's war effort. It also threatened British prosperity. British India was the only source of saltpeter. This was used in Union gunpowder. Within hours of the Trent Affair news, Russell stopped saltpeter exports. Two days later, the Cabinet banned the export of arms and ammunition. Britain was a main source of weapons for the Union army. Between May 1861 and December 1862, it supplied over 382,500 rifles. It also sent nearly 50 million percussion caps. One historian said that "British and European arms allowed the Union army to take the field early in the war."

The wider U.S. economy was soon hit by the Trent crisis. On December 16, news of the British cabinet's actions reached New York. The stock exchange fell. Government securities dropped. A financial collapse seemed near. On December 20, Salmon P. Chase's broker refused to sell some of his railway stock. He said it was almost worthless. He told Chase that the business community hoped he would calm things with England. He said, "one war at a time is enough." A run on New York banks followed. $17,000,000 was withdrawn in three weeks. On December 30, banks voted to stop paying in gold. Banks across the country soon followed. Only banks in Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky kept paying in coin. This meant the Treasury couldn't pay its suppliers, contractors, or soldiers. Though the crisis was solved soon after, these problems continued. On January 10, Lincoln asked Quartermaster General Meigs, "General, what shall I do? The people are impatient; Chase has no money... the General of the Armies has typhoid fever. The bottom is out of the tub." The Treasury had to print paper money called "greenbacks" to pay its bills.

With all the bad news, the official response from France also arrived. Dayton had already told Seward about his meeting with Thouvenel. The French foreign minister had said Wilkes' actions were "a clear breach of international law." But he also said France would "remain a spectator in any war between the United States and England." A direct message arrived on Christmas Day from Thouvenel. It urged the U.S. to release the prisoners. He said this would support the rights of neutral ships at sea. France and the U.S. had often argued for these rights against Great Britain.

Seward had written a draft of his reply to the British before the cabinet meeting. He was the only one with a clear plan. His main point was that releasing the prisoners matched America's long-held view on neutral rights. He believed the public would accept this. Both Chase and Attorney General Edward Bates were influenced by the messages from Europe. Postmaster Montgomery Blair had wanted to release the captives even before the meeting. Lincoln still wanted arbitration. But he got no support. The main problem was the time it would take. Britain was impatient. No decision was made at the meeting. A new meeting was set for the next day. Lincoln said he wanted to prepare his own paper. The next day, Seward's plan to release the prisoners was accepted. Lincoln did not offer a different argument. He later told Seward he couldn't write a good rebuttal to Seward's position.

Seward's reply was a "long, highly political document." Seward said Wilkes acted on his own. He denied British claims that the seizure was rude or violent. He said the capture and search of Trent followed international law. Wilkes' only mistake was not taking Trent to a port for a judge's decision. So, the prisoners had to be released. This was "to do to the British nation just what we have always insisted all nations ought to do to us." Seward's reply basically agreed that Wilkes treated the prisoners as contraband. It also compared their capture to the British practice of impressment. This response had some contradictions. Saying it was like impressment meant Mason and Slidell were taken because they were American. This was the opposite of America's past view. It referred to a right Britain hadn't used for 50 years. Also, Mason and Slidell were taken prisoner, not forced into the navy. So, it wasn't really relevant. More importantly, Seward's stance assumed there was a state of war. Otherwise, Union warships wouldn't have the right to search. At the time, the North was not only refusing to admit a state of war. It was also demanding Britain withdraw its recognition of Confederate belligerency.

Lyons was called to Seward's office on December 27. He was given the response. Lyons focused on the release of the prisoners. He didn't focus on Seward's legal analysis. Lyons sent the message and decided to stay in Washington. He would wait for more instructions. News of the release was published by December 29. The public reaction was mostly positive. Wilkes was among those against the decision. He called it "a craven yielding."

Mason and Slidell were released from Fort Warren. They boarded the Royal Navy ship HMS Rinaldo in Provincetown, Massachusetts. The Rinaldo took them to St. Thomas. On January 14, they left on the British mail ship La Plata for Southampton. News of their release reached Britain on January 8. The British saw it as a diplomatic victory. Palmerston noted that Seward's response had "many doctrines of international law" that Britain disagreed with. Russell wrote a detailed reply to Seward. He argued against Seward's legal ideas. But by this time, the crisis was over.

What Happened Next

The idea of recognizing the Confederacy as a country continued. British and French governments thought about it more in 1862. They considered offering to help end the war. As the war in America got worse, and the bloody results of the Battle of Shiloh were known, helping seemed more important. The Emancipation Proclamation was announced in September 1862. It made it clear that slavery was now a main issue of the war. At first, Britain thought this would only cause a slave rebellion in the South. They thought the war would become even more violent. Only in November 1862 did the push for European help reverse course.

Historians have praised Seward and Lincoln for how they handled the crisis. Seward always wanted to give the captives back. Lincoln knew war would be a disaster. He also had to deal with an angry public.

See also

Sources

Secondary sources

- Bourne, Kenneth. "British Preparations for War with the North, 1861–1862", The English Historical Review Vol 76 No 301 (Oct 1961) pp. 600–632 in JSTOR

- Campbell, W. E. "The Trent Affair of 1861,". The (Canadian) Army Doctrine and Training Bulletin. Vol. 2, No. 4, Winter 1999 pp. 56–65

- Carroll, Francis M. "The American Civil War and British Intervention: The Threat of Anglo-American Conflict." Canadian Journal of History (2012) 47 #1

- Chartrand, Rene. "Canadian Military Heritage, Vol. II: 1755–1871", Directorate of History, Department of National Defence of Canada, Ottawa, 1985

- Donald, David Herbert, Baker, Jean Harvey, and Holt, Michael F. The Civil War and Reconstruction. (2001) ISBN: 0-393-97427-8

- Ferris, Norman B. The Trent Affair: A Diplomatic Crisis. (1977) ISBN: 0-87049-169-5; a major historical monograph.

- Ferris, Norman B. Desperate Diplomacy: William H. Seward's Foreign Policy, 1861 (1976)

- Foreman, Amanda. A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (2011) excerpt

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. (2005) ISBN: 978-0-684-82490-1

- Graebner, Norman A. "Northern Diplomacy and European Neutrality", in Why the North Won the Civil War edited by David Herbert Donald. (1960) ISBN: 0-684-82506-6 (1996 Revision)

- Hubbard, Charles M. The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy. (1998) ISBN: 1-57233-092-9

- Jones, Howard. Union in Peril: The Crisis Over British Intervention in the Civil War. (1992) ISBN: 0-8032-7597-8

- Jones, Howard. Blue & Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2010) online.

- Mahin, Dean B. One War at A Time: The International Dimensions of the Civil War. (1999) ISBN: 1-57488-209-0

- Monaghan, Jay. Abraham Lincoln Deals with Foreign Affairs. (1945). ISBN: 0-8032-8231-1 (1997 edition)

- Musicant, Ivan. Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War. (1995) ISBN: 0-7858-1210-5

- Nevins, Allan. The war for the Union: The Improvised War 1861–1862. (1959)

- Niven, John. Salmon P. Chase: A Biography. (1995) ISBN: 0-19-504653-6.

- Peraino, Kevin. "Lincoln vs. Palmerston" in his Lincoln in the World: The Making of a Statesman and the Dawn of American Power (2013) pp. 120–69.

- Taylor, John M. William Henry Seward: Lincoln's Right Hand. (1991) ISBN: 1-57488-119-1

- Walther, Eric H. William Lowndes Yancey: The Coming of the Civil War. (2006) ISBN: 978-0-7394-8030-4

- Warren, Gordon H. Fountain of Discontent: The Trent Affair and Freedom of the Seas, (1981) ISBN: 0-930350-12-X

- Weigley, Russell F. A Great Civil War. (Indiana University Press, 2000) ISBN: 0-253-33738-0

Primary sources

- Baxter, James P., III. "Papers Relating to Belligerent and Neutral Rights, 1861–1865". American Historical Review (1928) 34 #1 in JSTOR

- Baxter, James P., III. "The British Government and Neutral Rights, 1861–1865." American Historical Review (1928) 34 #1 in JSTOR

- Fairfax, D. Macneil. "Captain Wilkes's Seizure of Mason and Slidell" in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: North to Antietam edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel. (1885).

- Hunt, Capt. O. E. The Ordnance Department of the Federal Army, p. 124–154, New York; 1911

- Moody, John Sheldon, et al. The war of the rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies; Series 3 – Volume 1; United States. War Dept., p. 775

- Petrie, Martin (Capt., 14th) and James, Col. Sir Henry, RE – Topographical and Statistical Dept., War Office, Organization, Composition, and Strength of the Army of Great Britain, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office; by direction of the Secretary of State for War, 1863 (preface dated Nov., 1862)

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |