James Murray Mason facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Mason

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office January 6, 1857 – March 4, 1857 |

|

| Preceded by | Jesse D. Bright |

| Succeeded by | Thomas J. Rusk |

| United States Senator from Virginia |

|

| In office January 21, 1847 – March 28, 1861 |

|

| Preceded by | Isaac S. Pennybacker |

| Succeeded by | Waitman T. Willey |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 15th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1837 – March 3, 1839 |

|

| Preceded by | Edward Lucas |

| Succeeded by | William Lucas |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Frederick County |

|

| In office December 1, 1828 – December 4, 1831 Serving with William Castleman, William Wood

|

|

| Preceded by | William Barton |

| Succeeded by | Constituency reestablished |

| In office December 4, 1826 – December 2, 1827 Serving with James Ship

|

|

| Preceded by | George Kiger |

| Succeeded by | William Barton |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Murray Mason

November 3, 1798 Analostan Island, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | April 28, 1871 (aged 72) Alexandria, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Eliza Chew |

| Education | University of Pennsylvania (BA) College of William and Mary (LLB) |

| Signature | |

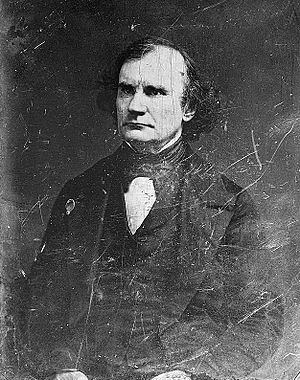

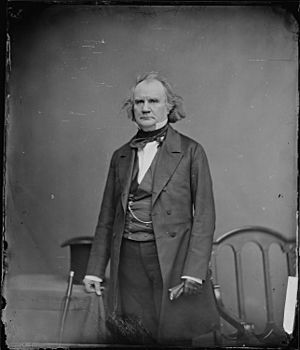

James Murray Mason (born November 3, 1798, died April 28, 1871) was a lawyer and politician from Virginia. He was the grandson of George Mason, a famous American Founding Father. James Mason served as a U.S. Senator for Virginia and was also a member of the Virginia House of Delegates.

Mason was a strong supporter of slavery and believed that states had the right to leave the United States. When the American Civil War began, he supported Virginia's decision to leave the Union. As a leading diplomat for the Confederate States of America, he traveled to Europe. His goal was to convince countries like the United Kingdom to recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation.

In November 1861, the U.S. Navy stopped his ship and held him. This event became known as the Trent Affair. After being released, Mason continued his mission but was unable to get European countries to officially support the Confederacy. After the war ended, he lived in Canada for a few years before returning to Virginia.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James Mason was born on Analostan Island, which is now called Theodore Roosevelt Island in Washington, D.C.. He went to the University of Pennsylvania and graduated in 1818. Later, he studied law in Williamsburg, Virginia, and earned a law degree from the College of William & Mary in 1820.

Political Career in Virginia

After becoming a lawyer, Mason practiced law in Virginia. He also managed a large farm in Frederick County. He soon entered politics, serving several times as a representative for Frederick County, Virginia, in the Virginia House of Delegates. His first term began in 1826.

In 1836, Mason was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives for Virginia's 15th district. He served one term in the Twenty-fifth United States Congress.

Serving in the U.S. Senate

In 1847, Virginia lawmakers chose Mason to fill a vacant seat in the United States Senate. He was re-elected in 1850 and 1856. Mason was known for his strong beliefs about states' rights and slavery. He famously read the final speech of Senator John C. Calhoun in 1850. This speech warned that the country might break apart if the Northern states did not accept slavery in the South and allow it to expand into new territories.

Mason also complained about "personal liberty laws" in the North. These laws were designed to help enslaved people who had escaped. From January to March 1857, Mason held the important position of President Pro Tempore of the Senate, meaning he led the Senate when the Vice President was not there.

Support for Slavery

Mason was a strong supporter of the Southern way of life, which included slavery. He believed that slavery was a natural condition and that Congress should not be able to stop it anywhere, including in new territories like Kansas.

He wrote the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a federal law that made it easier for slave owners to capture enslaved people who had escaped to free states. This law was very unpopular in the North. Mason also led a Senate committee that investigated John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, an attempt by an abolitionist to start a slave rebellion.

Advocating for Secession

Following the ideas of his mentor, John C. Calhoun, Mason strongly believed that states had the right to leave the Union. He felt that the North's opposition to slavery left the Southern states with no other choice but to secede.

Mason actively worked to help Virginia leave the Union in 1861. He stayed in the Senate for a while to gather information that could be useful to the Southern states. On July 11, 1861, Mason and other Southern senators were removed from the Senate because they were seen as being part of a plan to break up the United States.

Confederate Diplomat

After leaving the U.S. Senate, Mason became one of Virginia's representatives in the Provisional Confederate Congress. However, his main role was as a diplomat for the Confederacy.

The Trent Affair

In November 1861, Mason was on his way to England as a Confederate envoy (a special representative). He was traveling on a British ship called the RMS Trent. A U.S. Navy ship, the USS San Jacinto, stopped the Trent and captured Mason and another Confederate diplomat, John Slidell. They were held in a prison in Boston.

This event, known as the Trent Affair, almost caused a war between the United States and Britain. After careful talks, the U.S. government admitted that capturing the diplomats was against international law. Mason and Slidell were released on January 1, 1862, and continued their journey to England.

Mission in Europe

Mason represented the Confederacy in England, trying to get the British government to officially recognize the Confederacy as a country. He also discussed the Union's naval blockades. However, he was unsuccessful. After Britain refused to recognize the Confederacy in 1863, Mason moved to Paris, France. He continued his efforts there until April 1865, but no European nation recognized or helped the Confederacy.

Later Life and Death

During the Civil War, Mason's home in Winchester, Virginia, called "Selma," was taken over by the Union army. Because of Mason's strong support for slavery and his role in the Fugitive Slave Act, Union soldiers destroyed his house. They tore down the walls and used everything burnable for firewood. Mason never lived in Winchester again.

From 1865 to 1868, Mason lived in Canada. After the rules against Confederate officials were lifted, he returned to the United States. He bought a large property called the Clarens Estate in Alexandria, Virginia. He died at Clarens in 1871 and was buried in the churchyard of Christ Church (Alexandria, Virginia).

Family Life

James Mason married Eliza Margaretta Chew on July 25, 1822. They had eight children together:

- Anna Maria Mason Ambler (1825–1863)

- Benjamin Chew Mason (1826–1847)

- Catharine Chew Mason Dorsey (1828–1893)

- George Mason (1830–1895)

- Virginia Mason (1833–1920)

- Eliza Ida Oswald Mason (1836–1885)

- James Murray Mason, Jr. (1839–1923)

- John A. Mason (1841–1925)

He was also related to several other notable figures. His sister, Anna Maria, was married to Sydney Smith Lee, who was the father of Fitzhugh Lee, a Confederate Major General and later Governor of Virginia.

What Others Thought of Him

Carl Schurz's View

Carl Schurz, a visitor from Germany, met Senator Mason during a debate in Washington. Schurz described Mason as a "thick-set, heavily built man" who seemed to think he was better than others. Schurz felt that Mason's attitude was "supercilious" (meaning he thought he was superior) and that his speeches were often "pompous" (overly grand) and sometimes offensive.

Charles Sumner's View

Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who was against slavery, also spoke about Mason. Sumner called Mason the "author of the Fugitive Slave Bill" and criticized him for supporting slavery. Sumner said that Mason did not represent the "early Virginia" of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, who fought for equality and independence. Instead, Sumner felt Mason represented a Virginia where people were treated as property.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |