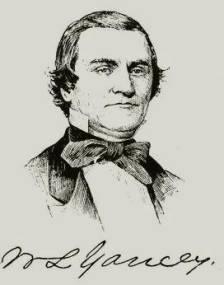

William Lowndes Yancey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

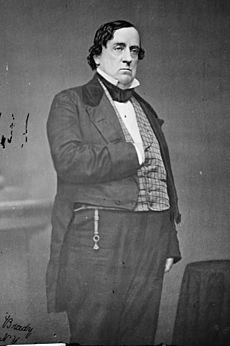

William Lowndes Yancey

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Confederate States Senator from Alabama |

|

| In office February 18, 1862 – July 27, 1863 |

|

| Preceded by | New constituency |

| Succeeded by | Robert Jemison |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Alabama's 3rd district |

|

| In office December 2, 1844 – September 1, 1846 |

|

| Preceded by | Dixon Lewis |

| Succeeded by | James Cottrell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 10, 1814 Warren County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | July 27, 1863 (aged 48) Montgomery, Alabama, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | Williams College |

William Lowndes Yancey (born August 10, 1814, died July 27, 1863) was an American politician and a key leader in the movement for Southern states to leave the United States. He was part of a group called the "Fire-Eaters", who strongly pushed for Southern states to break away. Yancey was known for his powerful speeches supporting this idea and defending slavery.

Even though he first disagreed with politician John C. Calhoun during a big debate in the 1830s, Yancey later joined Calhoun in opposing those who wanted to end slavery. By 1849, Yancey strongly supported Calhoun's ideas and was against the Compromise of 1850, a plan meant to settle disagreements over slavery.

In the 1850s, Yancey became famous for his long, captivating speeches. People sometimes called him the "Orator of Secession" because of his skill. At the 1860 Democratic Convention, he played a big role in splitting the Democratic Party. He strongly opposed Stephen A. Douglas and the idea of "popular sovereignty", which meant letting people in new territories decide on slavery for themselves. Yancey used the term "squatter sovereignty" to describe this idea.

During the American Civil War, Confederate President Jefferson Davis sent Yancey to Europe. His job was to convince countries like England and France to officially recognize the Southern states as an independent nation. However, Yancey was not successful in this mission. He returned to America in 1862 and was elected to the Confederate Senate. There, he often criticized President Davis's decisions. Yancey had poor health for most of his life and died during the Civil War in July 1863, at age 48.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Yancey was born on August 10, 1814, in Warren County, Georgia. His mother, Caroline Bird, lived on her family's plantation. His father, Benjamin Cudworth Yancey, was a lawyer. When William was three years old, his father died from yellow fever.

In 1821, Yancey's mother married Reverend Nathan S.S. Beman. The family moved to Troy, New York, in 1823, where Reverend Beman worked at a church. Reverend Beman was involved in the movement to end slavery, which was called abolitionism. Yancey's home life was difficult, and his parents separated in 1835. This troubled childhood may have influenced Yancey's later desire for public approval.

In 1830, when he was 16, Yancey started attending Williams College in Massachusetts. He was a good student and joined the debating society. He even edited a student newspaper for a short time. Yancey was involved in politics early, helping with a political campaign in 1832. Despite being chosen as the Senior Orator by his class, he left college in 1833, just before graduating.

Starting a Career in the South

After college, Yancey moved to Greenville, South Carolina. He lived on his uncle's plantation and worked as a bookkeeper. Many of Yancey's family members, including his birth father, supported keeping the United States together.

In 1834, Yancey gave a speech where he strongly supported the idea of a united nation. He spoke against those who wanted South Carolina to leave the Union.

Because of his political activities, Yancey became the editor of the Greenville Mountaineer newspaper in November 1834. As editor, he criticized John C. Calhoun, a leading politician who supported states' rights. Yancey compared Calhoun to Aaron Burr, saying they both tried to harm the country.

Yancey left the newspaper in May 1835. On August 13, he married Sarah Caroline Earl. As part of her dowry, Yancey received 35 enslaved people. This quickly made him part of the planter class, which owned large farms worked by enslaved people. In 1836, Yancey moved to his wife's plantation in Dallas County, Alabama. This was a tough time to move because cotton prices dropped sharply due to the Panic of 1837, hurting his finances.

In 1838, Yancey took over another newspaper, the Cahaba Southern Democrat. His first editorial strongly defended slavery. As his own financial situation worsened, Yancey began to see the anti-slavery movement as a threat. He started to support states' rights, a change from his earlier views. He also began to praise Calhoun's role in the "Gag Rule" debates, which tried to stop discussions about slavery in Congress. Yancey also criticized Henry Clay for supporting groups that wanted to send free African Americans to Africa.

In March 1839, Yancey sold his newspaper and moved to Wetumpka, Alabama. He planned to be a planter again. However, he faced a huge financial setback when some of his enslaved people were poisoned. Two died, and most others were sick for months. Unable to afford replacements, Yancey had to sell most of the recovering enslaved people. He then opened a new newspaper called the Argus and Commercial Advertiser in Wetumpka.

Serving in Public Office

Yancey became more and more interested in politics. His views shifted towards the most extreme part of the Southern Democratic Party. He was influenced by leaders like Dixon Hall Lewis. In 1840, Yancey started a weekly newsletter to support Martin Van Buren for president. He stressed that slavery was the most important issue for the South. While he didn't yet support secession, he was no longer fully committed to keeping the Union together.

In 1841, Yancey was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives and served for one year. In 1842, he sold his newspaper because of growing debt and decided to become a lawyer instead. In 1843, he successfully ran for the Alabama Senate. In this election, he focused on how enslaved people were counted for political representation, an issue that affected how much power different groups had in the state.

In 1844, Yancey was elected to the United States House of Representatives to fill an empty seat. He was re-elected in 1845. In Congress, his political skills and amazing speaking ability were quickly noticed. Yancey gave his first speech in January 1845, arguing for the annexation of Texas. His strong words led to a duel with Thomas Clingman of North Carolina, but neither person was hurt.

In Congress, Yancey spoke out against federal spending on internal improvements and high taxes on imported goods. He strongly supported states' rights and the start of the Mexican–American War. He also began to believe in conspiracy theories about the North's plans. In 1846, he resigned from his seat, partly due to money problems. He was also frustrated with Northern Democrats, whom he felt were betraying their principles for money.

The Alabama Platform

After leaving Congress, Yancey moved to Montgomery, Alabama. He bought a dairy farm and started a law firm. Although he was no longer a planter, he continued to own enslaved people. He owned 11 in 1850 and 24 by 1860. Yancey had suggested he might be done with politics, but he found it impossible to stay away.

Yancey understood how important the Wilmot Proviso was to the South. This proposal aimed to ban slavery in any new territories gained from Mexico. In 1847, Yancey hoped that Zachary Taylor, a slaveholder, might unite the South politically. Yancey said he would support Taylor only if Taylor spoke out against the Wilmot Proviso. However, Taylor decided to seek the Whig Party nomination. In December 1847, Lewis Cass, a leading Democratic candidate, supported "popular sovereignty." This meant letting people in new territories decide on slavery for themselves.

Since no candidate strongly opposed the Wilmot Proviso, Yancey pushed for the "Alabama Platform" in 1848. This platform was adopted by Alabama's Democratic convention and supported by other Southern states. It stated:

- The federal government could not limit slavery in the territories.

- Territories could not ban slavery until they were ready to become states.

- Alabama delegates would oppose any candidate who supported the Wilmot Proviso or popular sovereignty.

- The federal government must protect slavery in new territories.

When the national Democratic convention met in Baltimore, Cass was nominated. Yancey's platform was rejected. Yancey and another Alabama delegate left the convention in protest. His efforts to start a third party in Alabama failed.

In December 1848, a bill was introduced to end slavery in Washington, D.C.. This sparked more conflict between the North and South. In 1849, Yancey helped get Calhoun's "Southern Address" endorsed by Alabama Democrats. He also helped call for the Nashville Convention in June 1850.

Yancey opposed both the Compromise of 1850 and the results of the Nashville Convention. The convention did not call for secession as Yancey had hoped. Instead, it suggested extending the Missouri Compromise Line to the Pacific. Yancey helped create "Southern Rights Associations" in Alabama to push for secession. In February 1851, these associations produced Yancey's strong "Address to the People of Alabama."

This address stated that old political parties avoided taking action on slavery, allowing the South to be attacked. It also said that Southerners were treated as "inferiors" and "degraded" because of slavery. Despite Yancey's efforts, the Compromise of 1850 was popular, and unionist candidates won in Alabama and most of the South.

Leading to Secession

Yancey continued to support the most extreme Southern views. He is known as one of the "Fire-Eaters" who wanted the South to leave the Union. Historian Emory Thomas noted that Yancey, Edmund Ruffin, and Robert Barnwell Rhett were the loudest and longest supporters of secession. They wanted to preserve the South as it was, even if it meant a revolution.

When conflicts known as Bleeding Kansas broke out in 1855–1856, Yancey publicly supported efforts to send men to Kansas to fight for Southern interests. In 1856, he helped the Alabama Democratic Party adopt the Alabama Platform again. He also spoke at rallies supporting Preston Brooks, who had attacked Senator Charles Sumner. Yancey spoke about the differences between Northern and Southern people. In 1858, he supported William Walker, an adventurer who tried to take over Nicaragua, calling it a "cause of the South."

In the mid-1850s, Yancey also gave lectures to raise money for the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. This group bought and restored George Washington's home, Mount Vernon. Yancey helped raise $75,000 for this project.

At the 1858 Southern Commercial Convention in Montgomery, Yancey gave a long speech. He argued that if slavery was right, then importing enslaved people should also be right. He said, "We want negroes cheap, and we want a sufficiency of them, so as to supply the cotton demand of the whole world."

Yancey supported a plan by Edmund Ruffin to create a "League of United Southerners." This group would be an alternative to national political parties. In a letter in June 1858, Yancey wrote that no national party could save the South. He suggested organizing "Committees of Safety" in the cotton states. He believed this would "fire the Southern heart" and lead to a "revolution."

Yancey was sick for much of late 1858 and early 1859. By July 1859, he was able to speak publicly again, supporting the repeal of laws banning the slave trade. In late 1859, the Alabama Democratic Party chose Yancey to lead them at the upcoming national convention. They based their goals on the Alabama Platform. Yancey aimed to stop Stephen A. Douglas and popular sovereignty. By then, he also believed that secession would be necessary if a "Black Republican" (meaning Abraham Lincoln) won the presidency.

Spreading the Pro-Slavery Message

After 12 years, Yancey returned to the Democratic Party's national conventions in April 1860 in Charleston. The supporters of Stephen A. Douglas refused to accept a platform that protected slavery in the territories, like Yancey's Alabama Platform. When the platform committee presented such a proposal, it was voted down. Yancey and the Alabama delegation left the convention. They were followed by delegates from Mississippi, Louisiana, South Carolina, Florida, Texas, and Delaware. The next day, Georgia and Arkansas delegates also left. Yancey had successfully split the Democratic Party.

The convention could not nominate a candidate, so it met again in Baltimore in June 1860. Douglas supporters tried to unite the party by offering Yancey the vice-presidency, but he refused. Yancey's Alabama delegation was denied credentials in favor of a pro-Douglas group. Other Southern delegations also left the convention. The Southern representatives met separately in Baltimore on June 23. They adopted Yancey's platform and nominated John C. Breckinridge for president.

In a speech, Yancey criticized Douglas supporters, saying they ignored the dangers of abolition. Yancey had already given 30 public speeches in 1860 and gave 20 more during the campaign. He was now a national figure, making it clear that if anyone other than Breckinridge won, secession would follow.

Yancey's speaking tour for Breckinridge included stops in the North. In Wilmington, Delaware, he said, "We stand upon the dark platform of southern slavery, and all we ask is to be allowed to keep it to ourselves."

On October 10, 1860, at Cooper Union Hall in New York, Yancey advised Northerners to prepare for conflict if abolitionists gained power. He warned that abolitionists would spread ideas among enslaved people and that Southern whites would become "enemies of that race."

At Faneuil Hall in Boston, Yancey defended slavery. He said, "You are allowed to whip your children; we are allowed to whip our negroes. There is no cruelty in the practice. ... Our negroes are but children."

After touring many cities, Yancey returned to Montgomery on November 5. When news of Lincoln's election arrived, Yancey asked a crowd, "Shall we remain [in the Union] and all be slaves? ... God forbid!"

Secession of Alabama

On February 24, 1860, the Alabama legislature passed a resolution. It said that if a Republican was elected president, the governor must call for a state convention. After Lincoln's election, Governor Andrew Moore called for delegates to be elected on December 24. The convention would meet on January 7, 1861.

When the convention met, Yancey was a key leader. Delegates were divided: some wanted to secede immediately, while others wanted to wait and act with other Southern states. Yancey was frustrated with those who wanted to wait. He said that anyone who opposed secession would be siding with the federal government and should be treated as "public enemies."

Eventually, the ordinance of secession passed by a vote of 61 to 39.

When the Confederate States of America was formed later that month in Montgomery, Yancey was not a delegate. However, he gave the welcome address to Jefferson Davis, who was chosen as the provisional President. Many "Fire-Eaters" did not want a moderate like Davis as president, but Yancey accepted him. In his speech, Yancey said that with Davis, "The man and the hour have met." Historians agree that when Yancey and Davis met, the leadership of the revolution changed hands. Yancey and the radicals had started the movement, and Davis and the moderates would lead it.

During the War

Diplomat in Europe

Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Yancey met on February 18, 1861. Yancey turned down a cabinet position but said he would be interested in a diplomatic role. Some historians argue that Davis made a poor choice by appointing Yancey, who was not experienced in diplomacy. However, Davis might have wanted Yancey out of the country to avoid political opposition.

On March 16, Yancey was officially appointed head of a diplomatic mission to England and France. Ambrose Dudley Mann and Pierre Adolphe Rost were also part of the mission. The group arrived in London in late April. Their instructions were to convince Europe that Southern secession was right and legal. They also had to show that the Confederacy was strong, that cotton trade was valuable, and that the South would follow treaties. Most importantly, Yancey was to seek official diplomatic recognition for the Confederacy.

Yancey and his delegation met informally with British Foreign Secretary Lord John Russell in early May. Yancey explained his points and denied any plan to restart the slave trade. Russell did not commit to anything. On May 12, Queen Victoria announced that Britain would remain neutral but recognized that a state of war existed.

After news of the Confederate victory at Bull Run arrived, Yancey tried to meet Russell again. He had to present his arguments in writing. Some argue that Yancey made a mistake by praising slavery to the British. In August, Russell simply repeated Britain's decision to stay neutral. Critics say Yancey's mission failed to use opportunities or address British concerns about the war's impact. In late August, Yancey resigned. He stayed until his replacements, James Murray Mason and John Slidell, arrived in January 1862. Yancey made one more attempt to meet Russell after the Trent Affair, but Russell refused.

Yancey was initially hopeful about his mission. However, his talks and observations in British newspapers made him realize that slavery was the main barrier to diplomatic recognition. He told his brother, "Anti-slavery sentiment is universal. Uncle Tom's Cabin has been read and believed....I ought never to have come here. This kind of thing does not suit me."

Confederate Senate Service

While still in England, Yancey was elected to the Confederate Senate. Because of the Union blockade, he landed near the Texas and Louisiana border when he returned. On his way to Richmond, he stopped in New Orleans. There, he gave a public speech saying that Europe looked down on the Confederacy because of slavery. He stated, "We must rely on ourselves alone."

From March 28, 1862, to May 1, 1863, Yancey served in the Confederate Congress. He reluctantly supported the Confederate Conscription Act, which drafted men into the army. However, he helped allow many state exemptions, including an unpopular one for one overseer for every 20 enslaved people. He argued against too many secret sessions of Congress. He generally supported states' rights, opposing the federal Confederate government's power to take supplies and enslaved people.

On military matters, Yancey wanted details about reports of executions without trials by General Braxton Bragg. He questioned why Virginia had more generals than Alabama. He also wrote a resolution condemning drunkenness in the army.

Yancey gradually disagreed with President Davis on policy matters. Their differences grew in letters exchanged after May 1863. In Congress, Yancey and Benjamin Harvey Hill of Georgia had a physical fight over a bill to create the Confederate Supreme Court. Hill hit Yancey with an inkstand, knocking him to the floor. This fight was kept secret for months. In the investigation, Yancey, not Hill, was criticized.

Yancey returned to Alabama in May 1863, before Congress ended its session. By late June, he was very ill from his injuries from the attack by Hill. He continued to write to President Davis and others. On July 27, 1863, two weeks before his 49th birthday, Yancey died from kidney disease. His funeral on July 29, 1863, brought Montgomery to a halt. He was buried at Oakwood cemetery near the Alabama State Capitol.

Memorials

The William Lowndes Yancey Law Office in Montgomery, Alabama, was once recognized as a National Historic Landmark. It is still listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Images for kids

-

Jefferson Davis being sworn in as President of the Confederate States of America at the Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1861. Yancey had made the formal welcome address to Davis, stating that "The man and the hour have met." Later, Yancey would criticize many of Davis' actions.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |