Mount Vernon Ladies' Association facts for kids

The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union (MVLA) is a non-profit group that works to protect and care for the Mount Vernon estate. This was the home of George Washington and his family. The association was started in 1853 by Ann Pamela Cunningham from South Carolina. It is the oldest national group focused on saving historic places and the oldest women's patriotic society in the United States.

Ann Pamela Cunningham chose 30 women, called vice regents, from different states. These women worked together to raise $200,000 to buy the property. This was a huge amount of money back then! The MVLA took over Mount Vernon on February 22, 1860, and opened it as a museum. By saving this important national symbol, the MVLA hoped to bring people together and "heal" the disagreements that were growing in the country, especially about slavery in the United States. During the American Civil War, the MVLA's work paused, but it started again in 1866.

Today, the MVLA still does its original job. It gets all its money from private donations. A board of women from 27 states oversees the association.

Contents

Why Mount Vernon Needed Help

After George Washington passed away in 1799 and his wife Martha Washington in 1802, Mount Vernon stayed in their family for three generations. Eventually, George Washington's great-grandnephew, John Augustine Washington III, owned the property. But he didn't have enough money to keep it in good shape. By the mid-1800s, the famous Mansion House Farm was falling apart. In 1853, he offered to sell it to the state of Virginia, but they said no because the price was too high. He also offered to sell it to the U.S. government, but some important members of Congress felt the government shouldn't have to save every historical site.

A popular story says that one night in 1853, Louisa Bird Cunningham was on a steamboat on the Potomac River. As the boat passed Mount Vernon, the captain blew the horn. Louisa, who lived in South Carolina, was shocked to see how badly Washington's home had fallen apart. Writer Gerald W. Johnson later described it:

The paint was peeling from the walls, the roof was sagging, at least one of the great pillars along the front had collapsed and been replaced by wooden supports, the lawn was waist-high in wild weeds. It looked neglected, decaying, and deserted, and the passenger couldn't stop thinking about it.

Louisa Cunningham had an idea: the site should be fixed and saved as a national "shrine." The next day, Louisa wrote to her daughter, Ann Pamela Cunningham. The MVLA says she wrote:

If the men of America have allowed the home of its most respected hero to go to ruin, why can't the women of America join together to save it?

Ann Pamela Cunningham, who was 37 and suffered from constant pain from a horse-riding accident, was inspired by her mother's words. She decided to take on the huge task of saving and restoring Mount Vernon, even though her friends and family told her not to because of her health.

Starting the Fundraising Campaign

Focusing on Southern States

At first, Ann Pamela Cunningham focused on getting women from the Southern states to raise money for Mount Vernon. She was worried that "Northern capitalists" (rich business people) might buy Mount Vernon and turn it into a hotel.

On December 2, 1853, Cunningham wrote an open letter called "Appeal to the Ladies of the South." She used the fake name "A Southern Matron." The letter was first printed in the Charleston Mercury and then in other newspapers. In it, she asked other Southern women to help protect Mount Vernon from greedy business people and dishonest politicians. Her idea that good, patriotic women should act to save a national symbol was very brave for that time. Usually, it was "improper for a lady to take part in public affairs."

Cunningham also wrote to Eleanor Washington, asking her to convince her husband to wait to sell Mount Vernon. She hoped "the Southern ladies" would raise enough money to buy it and then give it to the governor of Virginia.

On February 22, 1854, the first public fundraising meeting happened at Cunningham's home in South Carolina. They raised $293.75. On July 12, 1854, a second meeting took place in Richmond, Virginia, to talk about forming an association. Thirty ladies and several gentlemen, including Governor Joseph Johnson, attended. More fundraising also happened in Georgia and Alabama.

Including Northern Women

By the fall of 1854, women from Northern states wanted to help. They said that "Washington belonged to the whole country." Cunningham realized she needed their help too, because raising $200,000 was very difficult.

Ann Pamela Cunningham knew there were strong feelings between the North and South. She worked hard to make the movement welcoming to Northern women without upsetting her Southern supporters. Many, including her own mother, wanted to keep the effort "all Southern." Cunningham argued that the goodness and patriotism of American women would help them overcome the sectionalism (strong loyalty to one's region) that was threatening to divide the country.

However, tensions between North and South still appeared. A committee in Philadelphia planned to give out flyers saying Mount Vernon would go to the U.S. Congress. When Cunningham told them it would go to the state of Virginia, the Philadelphia committee "dropped the whole like a hot potato." They even thought about asking Congress to buy it instead.

Meanwhile, the Virginia state committee said that as representatives of "Washington's native state," they should be the main committee. This went against Cunningham's efforts to encourage cooperation across the country. Cunningham saw the Virginia committee's actions as disobedient and worked to cancel their plans. This power struggle led to the resignation of Mary Anderson Gilmer. Her husband had argued that including Northern women was an "unholy alliance" that would "dirty the soil of Virginia with the polluted breath of Northern fanaticism."

Getting a Legal Charter

Following advice from John M. Berrien, a former U.S. senator and attorney general, Ann Pamela Cunningham worked to create the "Mount Vernon Association" as a modern nonprofit corporation. By getting a legal charter from the Virginia General Assembly, Cunningham would also secure her position as the main leader of the organization.

After Berrien's sudden death, James L. Petigru, a former attorney general of South Carolina and a strong supporter of the Union, took over writing the charter. He added the word "Ladies'" and "of the Union" to the association's name.

One important supporter of the 1856 charter was Anna Cora Mowatt, a famous actress. She had recently married William Foushee Ritchie, whose family was powerful in Virginia politics. Mrs. Ritchie met Cunningham in 1854 and quickly became the Secretary of the Central Committee of the early Mount Vernon Association. In the weeks before the bill was introduced in the Virginia legislature, Anna Cora Mowatt Ritchie held many parties at her home to get male support for the MVLA. Mrs. Ritchie told Cunningham:

I have been campaigning, and very successfully. The night before last I hosted a musical party, and asked my husband to invite as many Senators and members of the legislature as the house could hold... Everyone said they had a delightful evening. The music was excellent, and the supper good. Then came the big moment. As the Ladies began to leave, Mrs. Pellet started the topic with [former] Governor Floyd, and I soon managed to make it a general discussion. Governor Floyd promised to pass our bill right away – and so did all the other members and Senators present.

On March 15, 1856, O.W. Langfitt, a lawyer from Richmond, Virginia, brought the bill to the Virginia legislature. At first, the bill faced opposition. Some unhappy former members of the Virginia committee had spread rumors about internal problems in the organization. Also, there was hostility and doubt that such a big plan was being led by a woman. Since Cunningham was sick and in bed, Anna Cora Mowatt Ritchie stepped in. She rallied their supporters to continue discussing the bill and finally pass the association's founding charter.

On March 19, 1856, the Virginia state assembly passed a bill creating the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union. Ann Pamela Cunningham was named its leader. The charter also allowed the association to make a contract to own the Mount Vernon estate.

A Nationwide Organization

Choosing Leaders in Each State

As the leader of the new Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union, Ann Pamela Cunningham focused on building the organization across the country. With a small personal team, she chose a "Vice Regent" in each state to lead fundraising. Each vice regent then chose "Lady Managers" to help in specific areas within their state. The vice regents Cunningham picked usually came from wealthy families and were well-known in society. Many had ancestors who were Founding Fathers of the United States. Cunningham often repeated that the special "sisterhood" she had created would help the MVLA rise above the disagreements between the North and South.

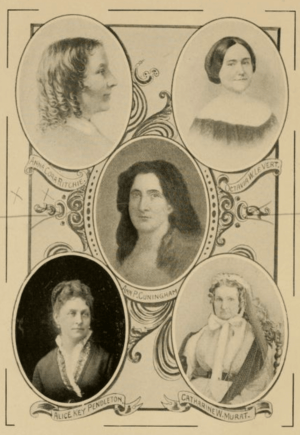

Historian Patricia West groups the early vice regents into three types: preservationists, figureheads, and activists. Preservationists like Anna Cora Mowatt Ritchie of Virginia and Octavia Walton Le Vert of Alabama were very interested in saving historical places. They were influenced by their travels in Europe. As an actress, Anna Cora Mowatt was especially excited about saving the birthplace of William Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon. Similarly, Madame Le Vert was impressed by how the home of the poet Ludovico Ariosto in Ferrara, Italy, had been bought by the government and kept as a "shrine" for visitors.

An example of a figurehead was Mary Chesnut, the vice regent of South Carolina. She served from 1860 until she passed away in 1861. She was the mother-in-law of Civil War diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut and had even met George Washington himself.

Among the activists was Mary Morris Hamilton of New York. She was the granddaughter of U.S. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. In her early years as vice regent, Hamilton raised almost $40,000. This was about one-fifth of the total price needed for Mount Vernon! Hamilton's lady managers for New York included Caroline C. Fillmore, the second wife of former President Millard Fillmore; former First Lady of New York Frances Adeline Seward; and the writer Caroline Kirkland. The New York committee also included the wives of historian George Bancroft and architect Andrew Jackson Downing.

Other vice regents who helped a lot included Louisa Ingersoll Gore Greenough of Massachusetts. She asked Anna Cora Mowatt to visit and do readings. Massachusetts managed to raise about $20,000 more than any amount credited to Edward Everett. Octavia Le Vert of Alabama raised over $10,000. Margaret Gordon Blanding of California raised $9,500. Lily Lytle Macalester of Pennsylvania raised almost $9,000, and North Carolina raised $8,000.

Other Supporters

Edward Everett, a well-known politician, was an early supporter of the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. He had been U.S. Secretary of State, a U.S. Senator, Governor of Massachusetts, and President of Harvard University. He believed Mount Vernon could be a strong symbol to unite the country and prevent a civil war.

Everett was a popular speaker. He later became known as "the other speaker at Gettysburg." Between 1856 and 1860, he gave his speech, "The Character of Washington," 137 times to audiences who paid to listen. He also signed a one-year contract with The New York Ledger to write a weekly column on American history. In return, he received an advance of $10,000, which he gave to the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association.

Everett chose three trustees in Boston to hold and invest the money he raised so it would earn interest. In the end, he gave a total of $69,024. This was a little more than one-third of the price needed to buy Mount Vernon.

While Everett gained support among Northerners by showing George Washington as a national hero, Southern secessionist leader William Lowndes Yancey raised money for the MVLA by touring the Southern states. He gave his own lectures praising Washington as a leader against government control. Yancey, a cousin of Ann Pamela Cunningham, was known for his "fierce sarcasm" as a speaker. He strongly defended the right to own slaves. So, both the Northern and Southern parts of the MVLA seemed to celebrate George Washington's legacy, even though they had opposite views on slavery and states' rights.

Challenges from Abolitionists

During their fundraising, the vice regents of the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association faced opposition from abolitionists (people who wanted to end slavery). These groups and others objected to Mount Vernon being a slave plantation. Vice Regent Abba Isabella Chamberlain Little of Maine reported that some Northerners refused to donate because of their beliefs. They felt it was wrong to support a place that had relied on slavery, even if it meant letting Washington's legacy fall to the South. In Minnesota, Vice Regent Sarah Jane Steele Sibley found that the main problems for fundraising were financial hardship from the Panic of 1857 (an economic downturn). People also felt uncomfortable that a slave plantation was considered a historical site worth saving. And there was a lack of enthusiasm from political opponents of her husband, Democratic Governor Henry Hastings Sibley.

In August 1858, suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton was praised in abolitionist newspapers for refusing Mary Morris Hamilton's invitation to be a lady manager for upstate New York. Stanton said she was "pledged to a higher and holier work than building monuments, or gathering up the sacred memories of the venerated dead." Instead, she felt that actively working to end slavery in the United States was the "purest" way to honor Washington's memory. Similarly, in November 1858, Elizabeth B. Chace turned down an invitation to be a lady manager for Rhode Island. She pointed out the irony of saying Mount Vernon had "moral value" as a symbol of America's fight for freedom, when one in six women in America were still enslaved.

Buying Mount Vernon

Ann Pamela Cunningham was alarmed when, shortly after the 1856 charter for the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union was passed, John Augustine Washington suddenly took the Mount Vernon estate off the market. He reportedly felt embarrassed by the charter's rule that he should give his estate to the MVLA instead of the state of Virginia. He was also clearly offended by the public criticism and personal attacks he had faced while the Virginia legislature discussed his "too high" asking price for Mount Vernon.

In June 1856, Cunningham visited John Augustine Washington in person to convince him to change his mind. Cunningham later wrote that she persuaded Washington by sharing his frustration that the state of Virginia had not wanted to own Mount Vernon. She said this moved him to tears. Meanwhile, John Augustine Washington wrote to William Foushee Ritchie that he still thought the MVLA's plan was "ridiculous." He predicted the women would manage the estate poorly and that Mount Vernon would eventually go back to Virginia anyway.

For the next few years, Cunningham stayed in regular contact with John Augustine Washington. She assured him that she was defending his honor – and his asking price for Mount Vernon – at every turn. Once, she sent him a newspaper article where she had criticized John Augustine Washington's critics as "a band of 'abolitionists' playing into the hands of 'speculators'."

On April 6, 1858, John Augustine Washington III finally signed a contract to sell Mount Vernon to the MVLA. He agreed to sell the mansion, other buildings, and 202 acres around them to the Association for $200,000. He received an immediate first payment of $18,000, with another $57,000 due in December. The rest was to be paid in four yearly payments on February 22, which is George Washington's birthday.

John Augustine Washington continued to cause national debate when, on December 25, 1858, he ran his third yearly advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette. It offered the services of his seven slaves for hire. Editor Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune published a harsh article condemning his actions. He encouraged the MVLA to finally take Mount Vernon away from him. Other abolitionists questioned if it made sense to donate money if John Augustine Washington refused to free his slaves.

In the end, the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union reached its fundraising goal. They paid the full amount in less than two years, even though there was an economic depression. John Augustine Washington and his family moved out of the mansion, and the MVLA finally took ownership of the estate on February 22, 1860.

After the Civil War

In 1874, Ann Pamela Cunningham wrote to the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association Council, announcing she was retiring as regent:

Ladies, the home of Washington is in your care – make sure you keep it the home of Washington. Let no disrespectful hand change it; no destructive hands ruin it with the ideas of progress. Those who go to the home where he lived and died want to see it as it was when he lived and died. Let one place in this great country of ours be saved from change. This duty rests upon you.

Efforts to preserve Mount Vernon continued through the late 1800s. In 1881, Alice Mary Longfellow, the oldest daughter of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, paid to restore and partly furnish Mount Vernon’s library. In 1888, women in Kansas raised $1,000 to rebuild the servants’ quarters (which were likely the slave quarters). Phoebe Hearst, the mother of newspaper owner William Randolph Hearst, donated $6,000 in 1895 to drain and fill a swamp near the mansion.

Other Preservation Projects

Protecting the View

Congresswoman Frances P. Bolton, who was a Vice Regent from Ohio from 1938 to 1977, started an effort in the 1940s to protect the view across the Potomac River. The Association bought 750 acres (3.0 km2) along the Maryland shore, which became the main part of the 4,000-acre (16 km2) Piscataway Park. This has helped keep the landscape looking as the Washingtons would have seen it.

George Washington's Books

On June 22, 2012, the Association bought Washington's personal copy of the United States Constitution at an auction for $9.8 million. This bound book was specially printed for Washington in 1789, his first year as president. It has his handwritten notes and marks. George Washington's books and papers bought by the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association are kept safe at The Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington.

Awards

- 2002 National Humanities Medal

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |