Gettysburg Address facts for kids

The Gettysburg Address is a very famous speech given by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. He delivered it on November 19, 1863, during the American Civil War. The speech was part of a special ceremony to open the Soldiers' National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This happened about four and a half months after the Union Army won a big battle against the Confederate States Army at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Many people think this speech is one of the greatest in American history. Lincoln talked about how all people are created equal, just like it says in the Declaration of Independence. He also explained that the Civil War was not just about keeping the Union together. It was also about bringing "a new birth of freedom" to make everyone truly equal in one united nation.

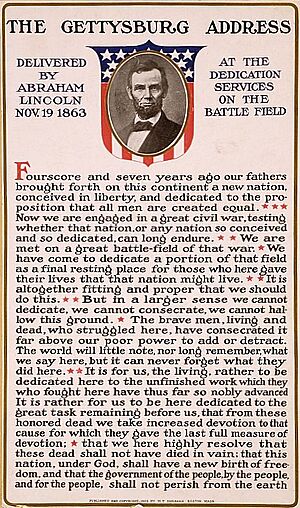

The speech starts with the famous words: "Four score and seven years ago." This refers to the American Revolution in 1776. A "score" is an old word for twenty. So, "four score and seven years" means 87 years. Lincoln used this ceremony to encourage people to support America's democracy. He wanted to make sure that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish (be destroyed) from the earth."

The Gettysburg Address is very important in American culture. However, people are not completely sure about the exact words Lincoln spoke. The five known handwritten copies of the speech are slightly different from each other. They are also different from what was printed in newspapers at the time.

Contents

The Story Behind the Speech

The Battle of Gettysburg happened from July 1 to 3, 1863. Around 172,000 American soldiers fought there. This battle was a major event in the Civil War. It also had a huge impact on the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, which only had about 2,400 people living there. After the battle, more than 7,500 dead soldiers and 5,000 horses were left on the battlefield. It was a terrible sight.

The people of Gettysburg wanted to bury the dead soldiers properly. A rich lawyer named David Wills helped buy 17 acres (about 69,000 square meters) of land for a cemetery. This cemetery would honor the soldiers who died in the battle. He paid $2,475.87 for the land.

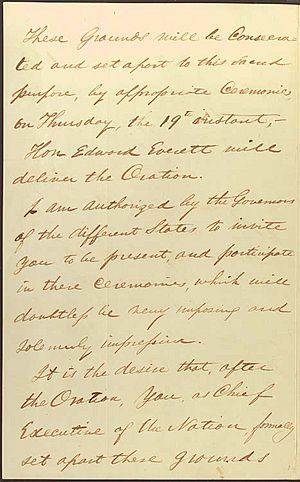

At first, Wills wanted to open the new cemetery on October 23. He asked Edward Everett to be the main speaker. Everett was a very famous speaker at that time. He had also been a Secretary of State, a U.S. Senator, and a governor. However, Everett said he needed more time to prepare a good speech. So, the ceremony was moved to Thursday, November 19.

Wills and the committee then invited President Lincoln to the ceremony. Lincoln was asked to join only 17 days before the event. Everett had received his invitation 40 days earlier! Wills's letter asked Lincoln to "formally (officially) set apart these grounds... by a few appropriate (proper) remarks." This showed that Lincoln was expected to have only a small part in the ceremony.

Lincoln arrived in Gettysburg by train on November 18. He spent the night at Wills's house. There, he finished the speech he had started writing in Washington, D.C.. There's a popular story that Lincoln wrote his speech on the back of an envelope on the train, but that's not true. He had already written most of it. On the morning of November 19, Lincoln rode a brown horse to the cemetery. He joined the townspeople and soldiers' widows marching to the dedication site.

About 15,000 people came to the ceremony. This included governors from six of the 24 Union states. Historians are not sure about the exact spot where the ceremony took place inside the cemetery.

Why the Speech Was Important

By August 1863, millions of people had been killed or hurt in the Civil War. Many people in the North were starting to dislike Lincoln and the war. Lincoln's plan to draft (force) men into the army in 1863 was very unpopular. This led to angry protests, like the New York Draft Riots, which happened just after the Battle of Gettysburg.

In September 1863, Pennsylvania's Governor Curtin told Lincoln that people were turning against the war. He said that if an election happened then, Lincoln might lose. People were very angry about the draft. They felt that Democratic leaders had turned many people against the war.

Lincoln was worried about losing the Presidential election in 1864. In late 1863, he was very concerned about keeping up the Union's spirit for the war. This was the main reason for Lincoln's speech at Gettysburg. He wanted to inspire people and remind them why they were fighting.

The Program and Other Speeches

The program for the day, planned by David Wills and his committee, included:

- Music, by Birgfield's Band

- Prayer, by Reverend T.H. Stockton, D.D.

- Music, by the Marine Band

- Oration (long speech), by Hon. Edward Everett

- Music, Hymn made by B.B. French, Esq.

- Dedicatory Remarks, by the President of the United States (Lincoln's speech)

- Dirge (sad song), sung by a chosen Choir

- Benediction (blessing), by Reverend H.L. Baugher, D.D.

Lincoln's short speech became one of the most famous public speeches in history. Edward Everett's two-hour speech was actually called the "Gettysburg address" that day. But today, almost no one remembers Everett's long speech.

Everett's speech began with very formal language:

- "Standing beneath this calm sky, overlooking these broad fields now resting from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the silence of God and Nature."

He finished two hours later by saying:

- "But they, I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that in the glorious history of our common country, there will be no brighter page than that which relates the Battles of Gettysburg."

The Words of the Gettysburg Address

After Everett finished his long speech, Lincoln spoke for only two or three minutes. Lincoln's "few appropriate remarks" summed up the war in just ten sentences.

Lincoln's speech is very important, but historians don't completely agree on the exact words he spoke. There are many different versions printed in newspapers from that time. The Bliss version, which Lincoln wrote for a friend sometime after the speech, is often seen as the most accurate. However, it's different from the versions Lincoln prepared before and right after his speech. The Bliss copy is the only one Lincoln signed, and it's the last one he is known to have written.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived (started, made) in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate...we can not consecrate...we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract (take away). The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve (decide) that these dead shall not have died in vain (for nothing)—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Where Lincoln Got His Ideas

Some historians, like Garry Wills, have noticed that Lincoln's speech is similar to Pericles' Funeral Oration. This was a famous speech given by Pericles during an ancient Greek war. Pericles' speech also started by remembering honored people, much like Lincoln's "our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation." Both speeches praised democracy and honored those who died for it. They also encouraged the living to keep fighting for freedom.

However, other writers, like Adam Gopnik, believe Lincoln's speech sounds more like the King James Bible. Gopnik said that Lincoln had mastered the sound of the Bible so well that he could talk about complex legal ideas using words that sounded like they came straight from the Bible.

There are many ideas about where Lincoln got the phrase "government of the people, by the people, for the people." William Herndon, Lincoln's law partner, wrote that he gave Lincoln sermons by an abolitionist minister named Theodore Parker. Parker had written: "Democracy is direct self-government, over all the people, for all the people, by all the people." Lincoln liked this phrase and marked it with a pencil.

Another idea is that Lincoln was influenced by a speech from Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster. In 1830, Webster described the government as "made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people." This is very similar to Lincoln's famous words.

Garry Wills also pointed out how Lincoln used ideas of birth, life, and death in his speech. Lincoln described the nation as "brought forth" and "conceived," and said it "shall not perish." Others suggest that Lincoln's phrase "four score and seven" comes from the King James Version of the Bible, specifically Psalms 90:10, which talks about human life as "threescore years and ten; and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years."

The Five Handwritten Copies

There are five handwritten copies of the Gettysburg Address that Lincoln himself wrote. Each copy is named after the person who received it from Lincoln. Lincoln gave a copy to each of his private secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay. These two copies were written around the time of his speech on November 19.

The other three copies (the Everett, Bancroft, and Bliss copies) were written much later, in 1864. Lincoln wrote these for charitable reasons, to be sold to help wounded soldiers. The Bliss copy is the most widely accepted version of the speech today. This is partly because Lincoln gave it a title, signed it, and dated it. It is the only copy Lincoln signed.

Both the Hay and Nicolay copies of the Address are kept at the Library of Congress. They are stored in special containers that protect them from damage.

Nicolay Copy

The Nicolay Copy is often called the "first draft." It is believed to be the earliest copy that still exists. Historians are not sure if this is the exact copy Lincoln read from at Gettysburg. Some parts of the Nicolay Copy don't match what was reported in newspapers as Lincoln's speech. For example, the words "under God" are missing from the phrase "that this nation (under God) shall have a new birth of freedom..." If this was the copy Lincoln read, it means he changed some words as he spoke. John Nicolay kept this copy until he died in 1901. It is now on display at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Hay Copy

The Hay Copy was found in 1906 among the papers of John Hay, Lincoln's other secretary. This copy is different from the version John Hay described in an article. It has many important words that Lincoln added or removed in his own handwriting. Like the Nicolay Copy, the words "under God" are not in this version.

This copy might have been made on the morning of the speech or soon after Lincoln returned to Washington. Some believe Lincoln used this copy when he gave the speech because it includes phrases that were reported in the newspapers but are not in the first draft. Lincoln later gave this copy to John Hay. Hay's family gave it and the Nicolay Copy to the Library of Congress in 1916.

Everett Copy

The Everett Copy is also known as the "Everett-Keyes Copy." Lincoln sent it to Edward Everett in early 1864. Everett had asked for it because he was putting together a book of speeches from the Gettysburg dedication to sell for wounded soldiers. This copy is on display at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois.

Bancroft Copy

Lincoln wrote the Bancroft Copy in February 1864 for the famous historian George Bancroft. Bancroft wanted to include this copy in a book to sell at a fair for soldiers and sailors in Baltimore. But Lincoln wrote on both sides of the paper, so it couldn't be used for the book. Bancroft was allowed to keep it. This copy is now kept at Cornell University. It is the only one of the five copies that is privately owned.

Bliss Copy

When Lincoln found out his fourth copy couldn't be used, he wrote a fifth one. This is the Bliss Copy, named after Colonel Alexander Bliss, Bancroft's stepson. Lincoln wrote this copy very carefully. He gave it a title—"Address delivered at the dedication of the cemetery at Gettysburg"—and signed and dated it. It was the only copy of the Gettysburg Address he signed. Because of this, it has become the most famous and widely used version of the speech.

Today, this copy hangs in the Lincoln Room of the White House. It was a gift from Oscar B. Cintas, who used to be the Cuban Ambassador to the United States. Cintas bought the Bliss Copy for $54,000 at an auction in 1949. He had stated in his will that the Gettysburg Address should go to the American people and be kept at the White House. It was moved there in 1959 and is still there today.

How People Reacted to the Speech

People who were there had different memories of how Lincoln's speech was received. Some said there was a respectful silence after he finished. An 87-year-old woman named Mrs. Sarah A. Cooke Myers, who was 19 at the time, said in 1931, "There was no applause when he stopped speaking." Historian Shelby Foote said the applause came after a long time and was "barely polite."

However, Pennsylvania's Governor Curtin said, "He pronounced (said) that speech in a voice that all the multitude (people) heard. The crowd was hushed into silence because the President stood before them... It was so Impressive!"

There's a story that Lincoln told his bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, that his speech "won't scour" (wouldn't be successful). But historian Garry Wills believes this story isn't true, as Lamon was the only one who remembered it. Wills felt that Lincoln achieved what he wanted to do at Gettysburg.

The day after the speech, Edward Everett wrote a letter to Lincoln. He praised the President, saying, "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central (main) idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes." Lincoln replied that he was glad the speech was not a "total complete failure."

Newspapers reacted differently depending on their political views. The Democratic Chicago Times called it "silly, flat and dishwatery." But the Republican New York Times praised the speech. The Republican newspaper in Springfield, Massachusetts printed the whole speech, calling it "a perfect gem" that was "deep in feeling, compact (simple) in thought and expression, and tasteful and elegant in every word and comma."

Audio Memories

William R. Rathvon is the only known eyewitness of the Gettysburg Address who left an audio recording of his memories. He recorded his thoughts and read the address in 1938, a year before he died. This recording was found in 1999 by National Public Radio (NPR). NPR often shares the recording around Lincoln's birthday.

Photographs

Only one confirmed photograph of Lincoln at Gettysburg exists. It was taken by David Bachrach. Lincoln's speech was short, but he and others sat for hours during the rest of the program. Because Everett's speech was so long, and old cameras took a long time to set up, photographers probably weren't ready for how quickly Lincoln finished his speech.

"Under God"

The Nicolay and Hay copies of the speech do not include the words "under God." However, these words appear in the three later copies (Everett, Bancroft, and Bliss). Some people wonder if Lincoln actually said "under God" at Gettysburg.

But at least three reporters who were there sent their reports of the speech with "under God" included. Historian William E. Barton said that all the reporters' notes, good or bad, included "that the nation shall, under God, have a new birth of freedom." He believed that the reporters could only have gotten those words from Lincoln's own mouth when he spoke. This suggests Lincoln probably added the phrase when he was speaking, even if it wasn't in his prepared notes.

The Speech's Lasting Impact

The Gettysburg Address is incredibly important in American history. It has been a part of American culture for a very long time. Many popular books and movies refer to the Gettysburg Address, assuming that people will know Lincoln's words. Even after many years, it remains one of the most famous speeches in American history.

Martin Luther King, Jr. mentioned the Gettysburg Address in his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. In August 1963, King spoke of President Lincoln and his well-known words: "Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This decree came as a great light of hope to millions of Negro slaves..."

The Constitution of France even includes a direct translation of Lincoln's words: "gouvernement du peuple, par le peuple et pour le peuple" ("government of the people, by the people, and for the people").

The address has become a part of American tradition. It is studied in schools and praised by writers. The Gettysburg Address offers an important understanding of the Declaration of Independence that is still remembered and used today. It is widely accepted as one of the most important documents in U.S. history, along with the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. To this day, it is one of the most famous, loved, and often quoted modern speeches.

Images for kids

-

One of the two confirmed photos of Lincoln (center, facing camera) at Gettysburg, taken about noon, just after he arrived and some three hours before his speech. To his right is his bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon.

-

The words of the Gettysburg Address carved inside the Lincoln Memorial.

See also

In Spanish: Discurso de Gettysburg para niños

In Spanish: Discurso de Gettysburg para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |