Edward Everett facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Everett

|

|

|---|---|

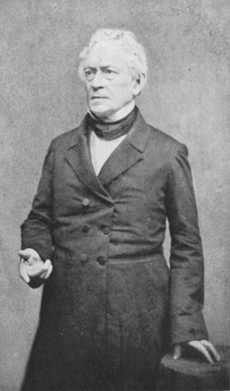

Edward Everett, 1860s

|

|

| 20th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office November 6, 1852 – March 4, 1853 |

|

| President | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | Daniel Webster |

| Succeeded by | William L. Marcy |

| United States Senator from Massachusetts |

|

| In office March 4, 1853 – June 1, 1854 |

|

| Preceded by | John Davis |

| Succeeded by | Julius Rockwell |

| 15th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 13, 1836 – January 18, 1840 |

|

| Lieutenant | George Hull |

| Preceded by | Samuel Turell Armstrong (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Marcus Morton |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 4th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1825 – March 3, 1835 |

|

| Preceded by | Timothy Fuller |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Hoar |

| United States Minister to the United Kingdom | |

| In office December 16, 1841 – August 8, 1845 |

|

| President | John Tyler James K. Polk |

| Preceded by | Andrew Stevenson |

| Succeeded by | Louis McLane |

| 16th President of Harvard University | |

| In office February 1846 – December 1848 |

|

| Preceded by | Josiah Quincy |

| Succeeded by | Jared Sparks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 11, 1794 Dorchester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | January 15, 1865 (aged 70) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | National Republican (Before 1834) Whig (1834–1854) Constitutional Union (1860–1864) National Union (1864–1865) |

| Spouse | Charlotte Gray Brooks |

| Children | 6 |

| Relatives | Alexander Hill Everett (Brother) Edward Everett Hale (Nephew) Lucretia Peabody Hale (niece) Susan Hale (niece) Charles Hale (nephew) |

| Education | Harvard University (BA, MA) University of Göttingen (PhD) |

| Signature | |

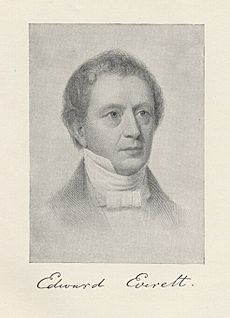

Edward Everett (born April 11, 1794 – died January 15, 1865) was an important American leader. He was a pastor, teacher, diplomat, and a great speaker from Massachusetts. Everett was a member of the Whig Party. He served in many high-level jobs. These included being a U.S. representative and a U.S. senator. He was also the 15th governor of Massachusetts. Later, he became the U.S. minister to Great Britain and the U.S. secretary of state. He also taught at and led Harvard University as its president.

Everett was known as one of the best speakers in America. He lived during the time leading up to the American Civil War and during the war itself. Many people remember him for his long speech at the dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery in 1863. He spoke for over two hours. This was right before President Abraham Lincoln gave his famous two-minute Gettysburg Address.

Edward Everett's father was a pastor. Edward went to Harvard University and became a pastor himself for a short time. He then took a teaching job at Harvard. This job allowed him to study in Europe for two years at the University of Göttingen. He also traveled around Europe for two more years. When he returned, he taught ancient Greek literature at Harvard. Later, he became very involved in politics and became a popular public speaker. He served ten years in the United States Congress. In 1835, he was elected Governor of Massachusetts. As governor, he started the Massachusetts Board of Education. This was the first state board of its kind in the country.

After losing the 1839 election for governor, Everett was made the U.S. Minister to Great Britain. He held this job until 1845. Next, he became the President of Harvard, but he didn't enjoy it much. In 1849, he worked with his friend Daniel Webster, who was the Secretary of State. After Webster died, Everett served as Secretary of State for a few months. Then he became a U.S. Senator for Massachusetts. In his later years, Everett traveled and gave speeches across the country. He worked to keep the United States together before the Civil War. In 1860, he ran for Vice President with the Constitutional Union Party. During the war, he strongly supported the Union. He also supported Lincoln in the 1864 election.

Contents

- Edward Everett's Early Life and Education

- Becoming a Pastor and Student in Europe

- Teacher, Writer, and Speaker

- Family Life and Marriage

- Edward Everett's Early Political Career

- Diplomatic Service Abroad

- Leading Harvard University

- Secretary of State and U.S. Senator

- Last Years and the Civil War

- Death

- Legacy and Remembrance

- Images for kids

- See also

Edward Everett's Early Life and Education

Edward Everett was born on April 11, 1794. He was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts, which was a separate town from Boston back then. He was the fourth of eight children. His parents were Reverend Oliver Everett and Lucy Hill Everett. His father was a pastor who retired due to poor health before Edward was born. Edward's father died in 1802 when Edward was eight years old. After his father's death, his mother moved the family to Boston.

Edward went to local schools, including Boston Latin School and Phillips Exeter Academy. At the young age of 13, he was accepted into Harvard College. In 1811, when he was 17, he graduated at the top of his class. Edward was a very serious and hardworking student. He learned everything he could.

Becoming a Pastor and Student in Europe

After college, Edward wasn't sure what to do. His pastor, Joseph Stevens Buckminster, encouraged him to study to become a minister. Edward did this and earned his master's degree in 1813. He became very good at writing and speaking. In November 1813, he became a permanent pastor at the Brattle Street Church. Edward was a very popular Unitarian preacher. People said he had a "florid and affluent fancy" and "daring imagery" in his speeches. However, Edward soon felt tired of the strict rules of preaching.

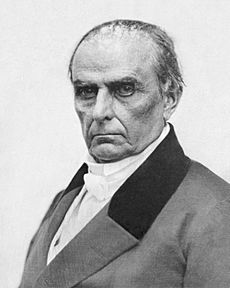

The hard work also made young Everett tired. He even got the nickname "Ever-at-it." For a change, he visited Washington, D.C. and met important people like Daniel Webster. In late 1814, Harvard offered Everett a new job as a professor of Greek literature. The job came with a chance to travel in Europe for two years. Edward happily accepted and became a professor in April 1815.

Everett traveled across Europe, visiting cities like London and Göttingen. At the university in Göttingen, he studied French, German, and Italian. He also learned about Roman law, archaeology, and Greek art. He was a very disciplined student. In September 1817, he earned his PhD, which he believed was the first such degree given to an American.

He spent two more years traveling around Europe, visiting many major cities. He met important people like Wilhelm von Humboldt, a Prussian diplomat, and William Wilberforce, an English abolitionist. While in Constantinople, Everett collected many old Greek texts. These are now kept in the Harvard archives.

Teacher, Writer, and Speaker

Everett started teaching at Harvard in 1819. He wanted to bring German scholarly methods and literature to the United States. He translated a Greek dictionary for his classes. Some of his students became famous, like Robert Charles Winthrop, Charles Francis Adams, Sr., and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson greatly admired Everett's speaking style. He wrote that Everett's voice was "the most mellow and beautiful and correct of all instruments of the time."

In 1820, Everett became the editor of the North American Review, a literary magazine. He wrote many articles for the magazine, which became very popular across the country. He also helped Harvard get more German books.

Everett began his public speaking career while teaching at Harvard. His speeches and his work as an editor made him well-known. In 1822, he gave a series of popular lectures in Boston about art and old artifacts. In 1823, he gave a major speech supporting the Greeks in their fight for independence from the Ottoman Empire. This speech made him a hero in Greece, and his picture is in the National Gallery in Athens. This also started a long political partnership with Daniel Webster.

Family Life and Marriage

On May 8, 1822, Edward Everett married Charlotte Gray Brooks (1800–1859). Her father, Peter Chardon Brooks, was a wealthy businessman. He helped support Everett financially when he started his political career. Through this marriage, Everett also became related to John Quincy Adams' son, Charles Francis Adams, Sr..

Edward and Charlotte had a happy marriage and raised six children:

- Anne Gorham Everett (1823–1843)

- Charlotte Brooks Everett (1825–1879)

- Grace Webster Everett (1827–1836)

- Edward Brooks Everett (1830–1861)

- Henry Sidney Everett (1834–1898)

- William Everett (1839–1910), who later became a U.S. Representative.

Edward Everett's Early Political Career

By 1821, Everett decided he didn't want to teach anymore. In July 1824, he gave an important speech at Harvard. The famous French hero of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette, was there. Everett's speech was about how America could create its own unique literature. He said that America's growth and democratic ideas gave its people a special chance to develop new ways of thinking.

The audience loved his speech. Soon after, Everett was nominated to run for the United States House of Representatives. He was easily elected in November 1824. He thought he could keep teaching at Harvard, but the university told him he was dismissed because he won the election. He accepted this news well. He continued to be involved with Harvard by joining its Board of Overseers in 1827.

Serving in the U.S. House of Representatives

In the late 1820s, American politics was changing. The Federalist Party had ended. Everett joined the "National Republican" group, which included John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. He supported Clay's "National System." This system called for tariffs (taxes on imported goods) to protect American industries, improvements like roads and canals, and a national bank. Everett was re-elected four times as a National Republican, serving until 1835. This group later became the Whig Party in 1834.

In Congress, Everett worked on committees dealing with foreign affairs and public buildings. He often visited President Adams at the White House. He supported laws that helped Massachusetts' growing industries. He also supported the national bank and was against the Indian Removal Act.

One of Everett's most debated actions in Congress happened in 1826. Congress was discussing changing how the president was elected. Everett gave a three-hour speech against the change. In his speech, he also talked about slavery. He said that the New Testament mentioned "Slaves obey your masters." He accepted the Constitution even though it included the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a person for representation.

This part of his speech caused a lot of criticism. People from both sides of politics attacked him. He tried to explain that he was against the slave trade and kidnapping people into slavery. But the damage was done. He was heavily criticized in the Massachusetts newspapers. This speech would follow Everett throughout his political life.

Becoming Governor of Massachusetts

Everett left Congress in 1835 because he didn't like the rough nature of debates there. In 1835, he was nominated by the Whig Party to run for governor of Massachusetts. He easily won against Marcus Morton, the candidate from the Democratic Party. He was re-elected three more times, always facing Morton.

One of Everett's biggest achievements as governor was creating a state board of education. This board was meant to improve school quality and set up normal schools to train teachers. Everett had learned about the Prussian education system, which inspired this idea. This was a new and important step for education in the U.S. The Massachusetts Board of Education was created in 1837. The first normal school opened in Lexington the next year.

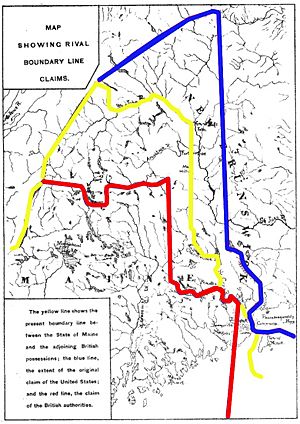

Other things Everett did as governor included approving an extension of the railroad system. He also helped calm border problems between Maine and the British province of New Brunswick (now part of Canada). Massachusetts was involved because it owned land in the disputed area. In 1838, Everett suggested to President Martin Van Buren that a special group be formed to solve the border issue.

Issues like abolitionism (ending slavery) and temperance (limiting alcohol) became more important during Everett's time as governor. These issues, along with some Whig Party actions, led to his defeat in the 1839 election. A new anti-slavery party, the Liberty Party, started forming in 1838. Also, a law banning the sale of small amounts of alcohol made many people unhappy with the Whigs. The 1839 election was very close. Marcus Morton won by just enough votes. Everett chose not to challenge the results, saying, "I am willing to let the election go."

Diplomatic Service Abroad

After leaving office, Everett traveled in Europe with his family. When the Whigs won the 1840 presidential election, Everett was appointed Ambassador to Great Britain. This was suggested by his friend Daniel Webster, who became Secretary of State.

Everett's first job was to handle the border issues in the northeast, which he knew about from being governor. A new British government was more friendly to the U.S. They sent Lord Ashburton to Washington to talk directly with Webster. Everett's role became getting documents from British records and explaining the American side to the British Foreign Office. Everett helped find and share a map that showed the U.S. was right in the 1842 Webster–Ashburton Treaty border agreement.

Another big problem was British naval forces stopping American ships off the coast of Africa. These forces were trying to stop the slave trade. Ship owners who were wrongly accused of being involved in the slave trade asked the British government for money. Everett, as ambassador, helped these cases. He was mostly successful because the British were friendly. Everett also suggested that the U.S. have its own ships off the coast of Africa to help stop the slave trade. This idea was included in the treaty Webster negotiated.

Everett turned down other diplomatic jobs offered by Webster. He stayed in his position until 1845. When James K. Polk became president, Everett was replaced by a Democrat. His last months were spent dealing with the Oregon boundary dispute. This issue was later solved by his replacement, but Everett had laid the groundwork.

Leading Harvard University

Even before he left London, people were thinking about Everett as the next President of Harvard. Everett returned to Boston in September 1845. He learned that Harvard had offered him the job. He had some doubts because of the boring parts of the job and the challenge of keeping students in line. But he accepted and started in February 1846.

His three years at Harvard were very unhappy. Everett found that Harvard didn't have enough money. Also, he wasn't popular with the unruly students. One of his main achievements was expanding Harvard's academic programs. He added a "school of theoretical and practical science," which became the Lawrence Scientific School. In April 1848, he gave a speech honoring John Quincy Adams, who had died two months earlier.

Everett was unhappy with the job early on. By April 1847, he was talking with Harvard's leaders about changing the job conditions. These talks didn't work out. In December 1848, Everett resigned, following his doctor's advice. He had been sick for some time. In the years that followed, his health became more fragile.

Secretary of State and U.S. Senator

When the Whigs won the 1848 election and returned to power in 1849, Everett went back into politics. He worked as an assistant to Daniel Webster, who was Secretary of State for President Millard Fillmore. When Webster died in October 1852, Fillmore appointed Everett to be Secretary of State. Everett served for the last few months of Fillmore's presidency.

In this job, Everett wrote the official letter for the Perry Expedition to Japan. He also changed Webster's decision about Peru's ownership of the guano-rich Lobos Islands. He refused to let the United States join an agreement with the United Kingdom and France to guarantee Spain's control of Cuba. He said that the U.S. didn't want to take over Cuba. But he also made it clear that the U.S. saw Cuba as its own concern, not a matter for other countries to interfere with.

While he was still Secretary of State, leaders from Massachusetts asked Everett to run for the United States Senate. He was elected by the state legislature and started his term on March 4, 1853. In the Senate, he served on the Foreign Relations Committee. He was against allowing slavery to spread into the western territories. However, he worried that the strong stance of the Free Soil Party would cause the country to split apart.

Everett was against the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act. This law allowed territories to decide if they would allow slavery by popular vote. He called it a "horrible" and "detested" bill. But because of his health, he missed a very important vote on the bill. He left the Senate chamber during a debate that lasted all night. This made anti-slavery groups in Massachusetts angry. They sent him a strong petition to present to the Senate. Everett's speech supporting the petition was weak. This was because he disliked the more extreme parts of the slavery debate. The anger of the situation greatly upset Everett. He resigned from the Senate on May 12, 1854, after only a little over a year. He again said his poor health was the reason.

Last Years and the Civil War

Free from political duties, Everett traveled the country with his family. He gave many public speeches. One cause he supported was saving George Washington's home at Mount Vernon. For several years in the mid-1850s, he gave speeches about Washington. Everett donated all the money he earned from these speeches, about $70,000. He also wrote a weekly column for the New York Ledger to raise more money for Mount Vernon. These columns were later published as the Mount Vernon Papers.

Everett was sad about the growing divisions between the Northern and Southern states in the late 1850s. In 1859, he was the main speaker at a large meeting against John Brown at Faneuil Hall.

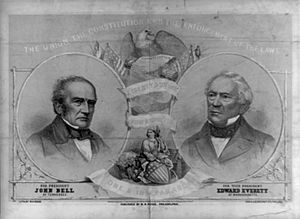

The 1860 election threatened to cause a national crisis. Southern states were talking about leaving the Union if a Republican president was elected. A group of conservative former Whigs formed the Constitutional Union Party. Their main goal was to keep the Union together. Supporters of Everett suggested him for president. But the party chose John Bell for president and Everett for vice president. Everett reluctantly accepted. The Bell–Everett ticket only won 39 electoral votes, all from Southern states.

After Abraham Lincoln was elected, seven Southern states began to seriously discuss leaving the Union. Everett actively tried to pass the Crittenden Compromise to avoid war in early 1861. When the American Civil War began in April 1861, he strongly supported the Union. At first, he didn't think highly of Lincoln, but he came to support him as the war went on. In 1861 and 1862, Everett toured the Northern states, giving lectures about the causes of the war. He also wrote for the New York Ledger to support the Union.

In November 1863, a military cemetery was dedicated at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Everett, known as the country's best speaker, was invited to be the main speaker. In his two-hour speech, he compared the Battle of Gettysburg to ancient battles. He talked about how opposing sides in past civil wars were able to make peace afterward. Everett's speech was followed by President Lincoln's much shorter, but now more famous, Gettysburg Address. Everett was very impressed by Lincoln's speech. He wrote to Lincoln, saying he wished he could have gotten "as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes." In the 1864 election, Everett supported Lincoln and served as a presidential elector for the Republicans in Massachusetts.

Death

On January 9, 1865, at age 70, Everett spoke at a public meeting in Boston. The meeting was to raise money for poor people in Savannah. He caught a cold there. Four days later, he testified for three hours in a legal case. This turned his cold into pneumonia. Edward Everett died in Boston on January 15, 1865. He was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge.

Legacy and Remembrance

Edward Everett Square, near his birthplace in Dorchester, is named after him. A marker is placed where his birthplace stood. A statue of Everett stands near the square in Richardson Park. Everett's name is on the front of the McKim Building of the Boston Public Library. He helped start the library and was president of its board for twelve years. His name was also given to his nephew, Edward Everett Hale, and Hale's grandson, the actor Edward Everett Horton.

The city of Everett, Massachusetts, which separated from Malden in 1870, was named in his honor. The borough of Everett, Pennsylvania, and Mount Everett in western Massachusetts are also named after him. Elementary schools in Dorchester and Lincoln, Nebraska are named for him. Everett donated 130 books to St. Cloud, Minnesota, starting the community's first library. The Edward Everett House in Charlestown was named a Boston Landmark in 1996.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Edward Everett para niños

In Spanish: Edward Everett para niños

- Lectionary 172

- Lectionary 296

- Lectionary 297

- Lectionary 298