Aaron Burr facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Aaron Burr

|

|

|---|---|

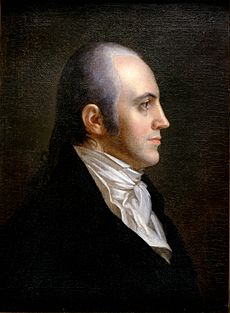

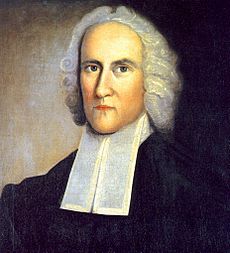

Portrait by John Vanderlyn, c. 1803

|

|

| 3rd Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1805 |

|

| President | Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Succeeded by | George Clinton |

| United States Senator from New York |

|

| In office March 4, 1791 – March 3, 1797 |

|

| Preceded by | Philip Schuyler |

| Succeeded by | Philip Schuyler |

| 3rd Attorney General of New York | |

| In office September 29, 1789 – November 8, 1791 |

|

| Governor | George Clinton |

| Preceded by | Richard Varick |

| Succeeded by | Morgan Lewis |

| Member of the New York State Assembly from New York County |

|

| In office July 1, 1784 – June 30, 1785 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Aaron Burr Jr.

February 6, 1756 Newark, Province of New Jersey, British America |

| Died | September 14, 1836 (aged 80) Staten Island, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Princeton Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 8 or more, including Theodosia, John, and Aaron |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Theodore Burr (cousin) |

| Education | College of New Jersey (BA) |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1775–1779 |

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel |

| Battles/wars | |

Aaron Burr Jr. (born February 6, 1756 – died September 14, 1836) was an important American politician and lawyer. He served as the third Vice President of the United States from 1801 to 1805. Burr is widely known for his conflict with Alexander Hamilton. This conflict ended with Burr shooting Hamilton in a duel in 1804. At that time, Burr was still the Vice President.

Burr came from a well-known family in New Jersey. He studied at Princeton before becoming a lawyer. In 1775, he joined the Continental Army as an officer during the American Revolutionary War. After leaving the army in 1779, Burr practiced law in New York City. He became a leading politician there. He also helped create the new Democratic-Republican Party. In 1785, as a New York Assemblyman, Burr supported a law to end slavery. This was even though he had owned slaves himself.

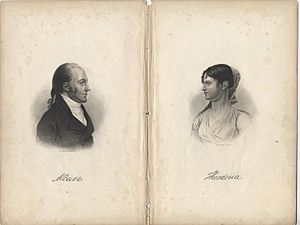

At age 26, Burr married Theodosia Bartow Prevost. She passed away in 1794 after 12 years of marriage. They had one daughter, also named Theodosia.

In 1791, Burr was elected to the U.S. Senate. He served there until 1797. Later, he ran for president as a Democratic-Republican in the 1800 election. There was a tie in the Electoral College between Burr and Thomas Jefferson. The House of Representatives then voted for Jefferson. Burr became Jefferson's vice president because he received the second-highest number of votes. Even though Burr said he supported Jefferson, the president was very suspicious of him. Burr was not given much power during his time as vice president. He was not chosen to run with Jefferson again in 1804.

During his last year as vice president, Burr fought a duel with Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton was a political rival. The duel took place near where Hamilton's son had died in a duel three years earlier. Dueling was against the law. However, Burr was never put on trial for Hamilton's death. All charges against him were eventually dropped. Still, Hamilton's death ended Burr's political career.

Burr then traveled west to the American frontier. He was looking for new chances in business and politics. His secret activities led to his arrest in Alabama in 1807. He was accused of treason. He faced trial more than once for what was called the Burr conspiracy. This was a supposed plan to create an independent country led by Burr. But he was found innocent each time. With many debts and few powerful friends, Burr left the United States. He lived in Europe for a few years. He came back in 1812 and started practicing law again in New York City. Burr's short second marriage ended in divorce. He suffered a stroke and lost all his money. Aaron Burr died in 1836 at a boarding house.

Contents

Early Life and Education

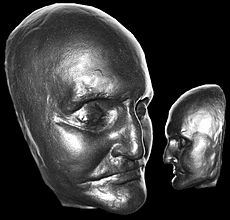

Aaron Burr Jr. was born in 1756 in Newark, New Jersey. He was the second child of Reverend Aaron Burr Sr.. His father was a Presbyterian minister and the second president of the College of New Jersey. This college later became Princeton University. His mother, Esther Edwards Burr, was the daughter of the famous religious leader Jonathan Edwards.

Burr's father died in 1757. His grandfather, Jonathan Edwards, then became president of the college. He moved in with Burr and his mother. But Edwards died in 1758. Burr's mother and grandmother also died that same year. This left Burr and his sister orphaned when he was only two years old. Young Aaron and his sister Sally were then cared for by their uncle, Timothy Edwards. Burr had a difficult relationship with his uncle. As a child, he tried to run away from home several times.

At age 13, Burr was accepted into Princeton as a sophomore. He joined the college's debating clubs. In 1772, at age 16, he earned his Bachelor of Arts degree. He continued studying religion for another year. He then decided to study law instead. At age 19, he moved to Connecticut to study law with his brother-in-law. In 1775, news of fighting with British troops reached him. Burr stopped his studies to join the Continental Army.

Serving in the Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, Burr joined Colonel Benedict Arnold's difficult journey to Quebec. This was a long trip of over 300 miles (480 km) through the wilderness of Maine. Arnold was impressed by Burr's "great spirit and resolution." Burr was promoted to captain and became an aide to General Richard Montgomery.

In 1776, Burr worked for George Washington in Manhattan. But he left to join the fighting on the battlefield. General Israel Putnam took Burr under his wing. Burr helped save an entire group of soldiers from being captured by the British. Washington did not praise his actions in the official orders. This upset Burr and may have caused problems between them later.

Burr was promoted to lieutenant colonel in July 1777. He took charge of a regiment of about 300 men. His group successfully fought off many nighttime attacks by British troops in New Jersey. Later that year, Burr commanded a small group during the harsh winter at Valley Forge. He kept order and stopped a planned mutiny by some soldiers.

In June 1778, Burr's regiment was badly hit by British artillery at the Battle of Monmouth. Burr suffered from heatstroke. In March 1779, due to poor health, Burr left the Continental Army. He went back to studying law. Even though he was no longer officially in the army, he still helped in the war. He sometimes carried out secret missions for generals. In July 1779, he helped lead a group of Yale students and soldiers against the British in Connecticut.

Marriage to Theodosia Bartow Prevost

Burr met Theodosia Bartow Prevost in August 1778. She was married to a British officer at the time. Burr began visiting Theodosia regularly at her home in New Jersey. Even though she was ten years older than Burr, their visits caused talk. By 1780, they were openly in love. In December 1781, Burr learned that Theodosia's husband had died.

Theodosia and Aaron Burr married in 1782. They moved to a house on Wall Street in Lower Manhattan. After several years of serious illness, Theodosia died in 1794. She had stomach or uterine cancer. Their only child to live to adulthood was Theodosia Burr Alston, born in 1783.

Law and Political Career

Burr finished his law studies and became a lawyer in 1782. He started practicing law in New York City in 1783.

Burr served in the New York State Assembly from 1784 to 1785. In 1784, he tried to pass a law to end slavery right after the Revolutionary War. This effort was not successful. He also continued his military service as a lieutenant colonel in the militia. In 1789, George Clinton appointed him as New York State Attorney General. In 1791, he was elected as a Senator from New York. He served in the Senate until 1797.

Burr ran for president in the 1796 election. He received 30 electoral votes, coming in fourth place. He was surprised by this loss. Many Democratic-Republican voters chose Jefferson but not Burr.

President John Adams appointed Washington as the head of U.S. forces in 1798. But he turned down Burr's request to become a general. Washington wrote that Burr was "a brave and able officer." But he questioned if Burr was also good at "intrigue." Burr was elected to the New York State Assembly again in 1798. He served there until 1799. During this time, he worked with the Holland Land Company. He helped pass a law that allowed people from other countries to own land.

New York City Politics

Burr quickly became a key figure in New York politics. He gained power through the Tammany Society, which later became Tammany Hall. Burr changed it from a social club into a powerful political group. This helped Jefferson become president, especially in New York City.

In 1799, Burr founded the Bank of the Manhattan Company. This bank may have caused more bad feelings between him and Hamilton. Before Burr's bank, Federalists controlled banking in New York. They had the federal government's Bank of the United States and Hamilton's Bank of New York. These banks lent money to big businesses. Hamilton had stopped other banks from forming in the city. Small business owners often struggled to get loans.

Burr asked for support from Hamilton and other Federalists. He said he was starting a much-needed water company for Manhattan. But he secretly changed the application for a state permit. He added the power to invest extra money in any legal way. Once approved, he stopped pretending to be a water company. He did dig a well and built a large water tank at his bank's site. Hamilton and others felt he had tricked them.

Burr's Manhattan Company was more than just a bank. It was a tool to help the Democratic-Republican party. Its loans went to party supporters. By lending money to small business owners, they could buy property. This allowed them to vote, increasing the party's voters. Federalist bankers in New York tried to stop lending money to Democratic-Republican businesses.

The 1800 Presidential Election

In the 1800 city elections, Burr used the Manhattan Company's power. He also used new campaign ideas to win New York's support for Jefferson. In 1800, New York's state legislature chose the presidential electors. Before the April 1800 elections, Federalists controlled the State Assembly. Burr's Democratic-Republican candidates for New York City were elected. This gave his party control of the legislature. In turn, New York's electoral votes went to Jefferson and Burr. This created more tension between Hamilton and Burr.

Burr worked with Tammany Hall to win the Electoral College votes. He became part of the Democratic-Republican presidential ticket in the 1800 election with Jefferson. Jefferson and Burr won New York. But they tied for the presidency overall, with 73 electoral votes each. Members of their party intended for Jefferson to be president and Burr to be vice president. But the tie meant the House of Representatives had to make the final choice. Each of the 16 states had one vote, and nine votes were needed to win.

Publicly, Burr stayed quiet. He did not give up the presidency to Jefferson, who was a big enemy of the Federalists. There were rumors that Burr and some Federalists were encouraging Republican representatives to vote for him. This would stop Jefferson from winning. However, there was no strong proof of such a plan. Most historians believed Burr was innocent. But in 2011, a historian found a letter that suggested Burr might have supported a secret plan to become president. This plan did not work, partly because Hamilton strongly opposed Burr. In the end, Jefferson became president, and Burr became vice president.

Vice Presidency (1801–1805)

Jefferson never trusted Burr. So, Burr was mostly kept out of party decisions. As Vice President, Burr was praised by some for being fair. He was a good leader as President of the Senate. He helped create some rules for that office that are still used today. Burr's fair leadership during the impeachment trial of Justice Samuel Chase helped protect the idea of judicial independence. This idea means judges can make decisions without political pressure. One newspaper said Burr led the trial with "the impartiality of an angel."

Burr was not chosen to run for a second term with Jefferson in 1804. George Clinton replaced Burr as Jefferson's vice president in 1805. Burr's farewell speech on March 2, 1805, made some of his toughest critics in the Senate emotional. This 20-minute speech was never fully written down. Only short parts and descriptions of it remain. In his speech, Burr defended the United States' system of government.

The Duel with Hamilton

When it was clear that Jefferson would not choose Burr for his ticket in the 1804 election, Burr ran for Governor of New York instead. Burr lost the election to Morgan Lewis. This was the biggest loss margin in New York's history at that time. Burr blamed his loss on a negative campaign. He believed his political rivals, including New York governor George Clinton, were behind it. Alexander Hamilton also opposed Burr. Hamilton believed Burr had supported a plan for New York to leave the United States.

In April, a newspaper published a letter. It quoted Hamilton saying Burr was "a dangerous man." It also claimed Hamilton had an even worse opinion of Burr. In June, Burr sent this letter to Hamilton. He asked Hamilton to confirm or deny these statements.

Hamilton replied that Burr should give specific details of Hamilton's remarks. He said he could not answer about someone else's interpretation. More letters were exchanged. Burr then demanded that Hamilton take back or deny any statement that hurt Burr's honor over the past 15 years. Hamilton, worried about his reputation, did not. Burr then challenged Hamilton to a duel. A duel was a formal fight under specific rules.

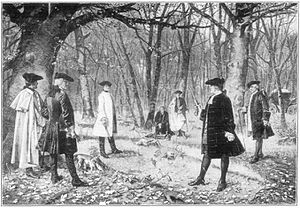

Dueling was against the law in New York and New Jersey. On July 11, 1804, the two men met in Weehawken, New Jersey. This was the same place where Hamilton's oldest son had died in a duel three years before. Both men fired their pistols. Hamilton was seriously wounded by a shot just above his hip.

People who saw the duel disagreed on who fired first. But they agreed there was a few-second gap between the shots. Historians have different ideas about what happened. Some suggest Hamilton's pistol might have been set to fire very easily. Others say Hamilton told friends he planned to shoot into the air. Hamilton wrote letters before the duel saying he did not intend to hit Burr. Witnesses said the second shot came so fast after the first that they couldn't tell who fired first. Before the duel, Hamilton took time to get used to the pistol. He also put on his glasses to see better.

Each man fired one shot. Burr's shot badly wounded Hamilton. Hamilton's shot was fired into the air. Hamilton was taken to a friend's home in Manhattan. He died there. Burr was accused of crimes, including murder, in New York and New Jersey. But he was never put on trial in either state.

He went to South Carolina, where his daughter lived. But he soon returned to Philadelphia and then Washington to finish his term as vice president. He avoided New York and New Jersey for a while. But all the charges against him were eventually dropped. In New Jersey, the case was dismissed. This was because Hamilton was shot in New Jersey but died in New York.

Life After Vice Presidency (1805–1836)

The Burr Conspiracy and Trial

After Burr left the vice presidency in 1805, he traveled to the Western frontier. This included areas west of the Allegheny Mountains and down the Ohio River Valley. He eventually reached the lands bought in the Louisiana Purchase. Burr had rented 40,000 acres (16,000 ha) of land in present-day Louisiana from the Spanish government. He traveled through several towns, gathering support for his planned settlement. The exact purpose of this settlement was unclear.

His most important contact was General James Wilkinson. Wilkinson was the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Army in New Orleans. He was also the Governor of the Louisiana Territory. Others, like Harman Blennerhassett, offered their private island for training Burr's group. Wilkinson later proved to be untrustworthy.

Burr thought war with Spain was very likely. If war was declared, Andrew Jackson was ready to help Burr. Burr's group of about eighty men carried hunting weapons. No war supplies were ever found. Burr always said his plan was to settle there with armed "farmers." If war broke out, he would have a force to fight and claim land for himself. This would help him regain his wealth. However, the war Burr expected did not happen.

After a small incident with Spanish forces, Wilkinson decided to betray Burr. He told President Jefferson about Burr's plans. Jefferson ordered Burr's arrest, calling him a traitor before any official charges. Burr read about this in a newspaper in 1807. Jefferson's order sent federal agents after him. Burr turned himself in twice. Both times, judges found his actions legal and released him.

However, Jefferson's warrant still followed Burr. Burr fled towards Spanish Florida. He was stopped in Wakefield, in Mississippi Territory (now Alabama), on February 19, 1807. He was held at Fort Stoddert after being arrested for treason.

Burr's secret letters with British and Spanish ministers were later revealed. He had tried to get money. He also tried to hide his true goal: to help Mexico overthrow Spanish rule in the Southwest. If Burr planned to create his own kingdom in former Mexican territory, this was a minor crime. It was based on a law passed to stop private military expeditions against U.S. neighbors. However, Jefferson wanted the most serious charges against Burr.

In 1807, Burr was tried for treason in Richmond, Virginia. His defense lawyers included famous attorneys. Burr had been accused of treason four times before a grand jury officially charged him. The only physical evidence shown to the Grand Jury was a letter supposedly from Burr, written by Wilkinson. Wilkinson said he had lost the original. The Grand Jury rejected the letter as evidence. This made Wilkinson look foolish during the trial.

The trial was led by Chief Justice John Marshall. It began on August 3. The U.S. Constitution says treason must be admitted in court or proven by two witnesses to an overt act. Since no two witnesses came forward, Burr was found innocent on September 1. This happened even though the Jefferson administration strongly pushed for his conviction. Burr was immediately tried on a minor charge and was again found innocent.

Jefferson used his power as president to try to get a conviction. So, the trial was a major test of the Constitution. It also tested the idea of separation of powers. Jefferson challenged the Supreme Court's authority. He believed Burr's treason was clear. Burr had sent a letter to Jefferson saying he could harm him. The case was decided on whether Aaron Burr was present at certain events. Jefferson used all his influence to get Marshall to convict. But Marshall was not swayed.

Some historians believe that while Burr was not guilty of treason by Marshall's definition, there is evidence linking him to treasonous acts. For example, one person admitted that Burr planned to raise an army and invade Mexico. He said Burr believed he should be Mexico's ruler. Many historians think the full extent of Burr's involvement may never be known.

Exile and Return to America

After his treason trial, even though he was found innocent, all of Burr's hopes for a political comeback were gone. He left America to escape his creditors and lived in Europe. A friend, Dr. David Hosack, lent Burr money for his ship passage.

Burr lived in self-imposed exile from 1808 to 1812. He spent most of this time in England. He became good friends with the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham. He also spent time in Scotland, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, and France. He hoped to get money to restart his plans for Mexico. But he was turned down. He was ordered out of England. Emperor Napoleon of France refused to meet him.

After returning from Europe, Burr used the last name "Edwards" for a while. This was his mother's maiden name. He did this to avoid people he owed money to. With help from old friends, Burr returned to New York. He started his law practice again. By the early 1820s, the remaining members of the Eden family became like a second family to Burr.

Later Life and Death

Despite money problems, Burr lived the rest of his life in New York in relative peace until 1833.

On July 1, 1833, at age 77, Burr married Eliza Jumel. She was a rich widow 19 years younger than him. They lived briefly at her home, the Morris–Jumel Mansion in Manhattan. This mansion is now a preserved historic site open to the public.

Soon after the marriage, Jumel realized her money was disappearing. This was due to Burr's bad land investments. So, she separated from him after four months of marriage. She chose Alexander Hamilton Jr. as her divorce lawyer in 1834. That same year, Burr suffered a stroke that left him unable to move well. He died on Staten Island in the village of Port Richmond. This was in a boardinghouse that later became the St. James Hotel. He died on September 14, 1836, the same day his divorce was finalized. He was buried near his father in Princeton, New Jersey.

Personal Life

Besides his daughter Theodosia, Burr was a father to at least three other children. He also adopted two sons. Burr acted as a parent to his two stepsons from his wife's first marriage. He also mentored several young people who lived in his home.

Burr's Daughter Theodosia

Theodosia Burr was born in 1783 and named after her mother. She was the only child of Burr's marriage to Theodosia Bartow Prevost to live to adulthood. Another daughter, Sally, lived to be three years old.

Burr was a loving and caring father to Theodosia. He believed that young women should have the same education as young men. So, Burr planned a strict course of study for her. It included classic books, French, horseback riding, and music. Their letters show that he treated his daughter as a close friend.

Theodosia became well known for her education and achievements. In 1801, she married Joseph Alston of South Carolina. They had a son, Aaron Burr Alston, who died at age ten. In the winter of 1812–1813, Theodosia was lost at sea. Her ship, the Patriot, disappeared off the Carolinas. It is believed she was either attacked by pirates or lost in a storm.

Stepchildren and Other Young People

When Burr married, he became a stepfather to his wife's two teenage sons. They had joined their father in the Royal American Regiment in 1780. When they returned in 1783, Burr acted as a father to them. He was in charge of their education. He gave them jobs in his law office. He often took one of them as an assistant when he traveled for work. One son, John, was later appointed by Thomas Jefferson as the first judge of the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Burr also cared for Nathalie de Lage de Volude from 1794 to 1801. She was the young daughter of a French nobleman. Nathalie had been brought to New York for safety during the French Revolution. Burr welcomed them into his home. Nathalie became a close friend to Theodosia. In 1801, Nathalie traveled to France. There, she met Thomas Sumter Jr., a diplomat. They married in Paris in 1802.

In the 1790s, Burr also took the painter John Vanderlyn into his home. He supported him financially for 20 years. He arranged for Vanderlyn to train with a famous painter. He also sent him to study art in Paris for six years.

Adopted and Acknowledged Children

Burr adopted two sons, Aaron Columbus Burr and Charles Burdett. This happened in the 1810s and 1820s, after his daughter Theodosia died. Aaron was born in Paris in 1808 and came to America around 1815. Charles was born in 1814.

Both boys were thought to be Burr's biological sons. One of Burr's biographers said Aaron Columbus Burr was "the product of a Paris adventure." This likely happened during Burr's time in Europe.

In 1835, the year before he died, Burr acknowledged two young daughters. He had fathered them later in his life with different mothers. Burr made special plans for his surviving daughters in his will. He left most of his money to six-year-old Frances Ann and two-year-old Elizabeth.

Unacknowledged Children

Around 1787, Burr began a relationship with Mary Emmons. She was also known as Eugenie and may have been from East India. She worked as a servant in his home during his first marriage. Burr had two children with Emmons. Both of them married into Philadelphia's "Free Negro" community. Their families became well-known there.

- Louisa Burr (Webb) (Darius) (born around 1784 – died 1878) worked most of her life as a valued servant. Her youngest son, Frank J. Webb, wrote a novel in 1857.

- John Pierre Burr (born around 1792 – died 1864) became part of Philadelphia's Underground Railroad. He helped people escape slavery. He also worked for an abolitionist newspaper.

One person who knew John Pierre Burr said he was Burr's natural son. But Burr never publicly acknowledged his relationship or children with Emmons during his life. This was different from how he treated other children born later.

In 2018, Louisa and John were recognized by the Aaron Burr Association as Burr's children. This happened after a descendant provided proof, including DNA test results. The Association placed a headstone at John Pierre's grave to mark his ancestry.

Character and Beliefs

Aaron Burr was a complex person. He made many friends but also many powerful enemies. He was accused of murder after Hamilton's death. But he was never put on trial. People who knew him said he seemed unaffected by Hamilton's death. He showed no regret for his part in it. He was arrested and tried for treason by President Jefferson. But he was found innocent. People often remained suspicious of Burr's motives. They continued to see him as untrustworthy.

In his later years in New York, Burr provided money and education for several children. Some were believed to be his own children. To his friends, family, and even strangers, he could be kind and generous. The wife of a struggling poet wrote that Burr once pawned his watch to help care for her children. She said Burr "wept" and quickly pawned his watch for twenty dollars. He gave the money to make her children comfortable.

Burr believed women were as smart as men. He had a portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft hanging in his home. She was a writer who supported women's rights. The Burrs' daughter, Theodosia, learned dance, music, several languages, and how to shoot from horseback. She remained devoted to her father until her death. Not only did Burr support education for women, but he also tried to pass a law that would have allowed women to vote. This bill did not pass. Hamilton criticized Burr for supporting the idea that women were equal to men.

Burr also spoke out against negative feelings towards immigrants. Hamilton's party suggested that anyone without English heritage was a second-class citizen. They even questioned the rights of non-English people to hold office. Burr insisted that anyone who helped society deserved all the rights of any other citizen, no matter their background.

John Quincy Adams wrote in his diary when Burr died: "Burr's life, take it all together, was such as in any country of sound morals his friends would be desirous of burying in quiet oblivion." Adams' father, President John Adams, had often defended Burr during his life. He once wrote that Burr "had served in the army, and came out of it with the character of a knight without fear and an able officer."

Historian Gordon S. Wood believes Burr's character caused problems with other "founding fathers." These included Madison, Jefferson, and Hamilton. Wood thinks this led to Burr's political defeats. It also led to him being outside the group of respected revolutionary figures. Burr's enemies thought he put his own interests above the good of the country. They believed he was a threat to the ideals of the revolution. They believed leaders should act for the public good, not for personal gain. Hamilton thought Burr's self-serving nature made him unfit for office.

Hamilton saw Jefferson as a political enemy. But he believed Jefferson was a man who cared about the public good. Hamilton worked hard to stop Burr from becoming president. He wanted Jefferson to win instead. Hamilton described Burr as very immoral. He said Burr cared little about the Constitution. He predicted that if Burr gained more power, he would use it for himself. Hamilton said Jefferson was a true patriot who wanted to protect the Constitution.

Legacy and Impact

Even though Burr is often remembered for his duel with Hamilton, he also left important marks on American history. His work in setting up rules for the first impeachment trial created high standards for behavior in the Senate. Many of these rules are still followed today.

Historian Nancy Isenberg explains that Burr's bad reputation might come from a negative campaign. His political enemies started this campaign centuries ago. They spread it through newspapers and letters during and after his life. She says that popular stories about Burr have just repeated these ideas. This has made Burr seem like the ultimate bad guy of early American history. Stuart Fisk Johnson describes Burr as a forward-thinking person. He was a brave military hero and a brilliant lawyer. He helped build some of America's physical structures and legal ideas.

A lasting result of Burr's role in the election of 1800 was the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This amendment changed how vice presidents are chosen. The 1800 election showed that the vice president, as the losing presidential candidate, might not work well with the president. The Twelfth Amendment required that electoral votes be cast separately for president and vice president.

Burr is sometimes seen as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. However, this is not a common view.

Aaron Burr in Books and Pop Culture

- Burr appears as a sophisticated character in Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1859 book The Minister's Wooing.

- Edward Everett Hale's 1863 story "The Man Without a Country" is about a made-up person who worked with Burr. This person is exiled for his crimes.

- My Theodosia (1945) by Anya Seton is a fictional story about Burr's daughter Theodosia.

- In The Jack Benny Program episode "The Alexander Hamilton Show", Jack Benny dreams he is Alexander Hamilton; Dennis Day plays Burr.

- Gore Vidal's Burr: A Novel (1973) is part of his historical book series.

- A 1993 "Got Milk?" commercial features a historian who loves studying Aaron Burr. He owns the guns and bullet from the duel.

- PBS's American Experience episode "The Duel" (2000) told the story of the Burr–Hamilton duel.

- Burr is a main character in the 2015 Broadway musical Hamilton. It was written by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Leslie Odom Jr. won an award for playing Aaron Burr.

See also

In Spanish: Aaron Burr para niños

In Spanish: Aaron Burr para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |