Morris–Jumel Mansion facts for kids

|

Morris–Jumel Mansion

|

|

|

U.S. Historic district

Contributing property |

|

The front facade in 2014

|

|

| Location | 65 Jumel Terrace in Roger Morris Park, bounded by West 160th Street, Jumel Terrace, West 162nd Street, and Edgecombe Avenue Washington Heights, Manhattan New York City |

|---|---|

| Built | 1765, remodeled c. 1810 |

| Architectural style | Palladian, Georgian, and Federal |

| Part of | Jumel Terrace Historic District (ID73001220) |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000545 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | January 20, 1961 |

| Designated CP | April 3, 1973 |

The Morris–Jumel Mansion is a very old house in the Washington Heights area of New York City. It was built in 1765, making it the oldest house still standing in Manhattan. A British officer named Roger Morris built it. Later, in the 1800s, a famous socialite named Eliza Jumel lived there with her family.

The city of New York has owned the house since 1903. Today, it is a historic house museum where you can learn about its past. The house is a special landmark, recognized by both New York City and the United States government. It is also part of the Jumel Terrace Historic District.

Roger Morris built the house for himself and his wife, Mary Philipse Morris. They lived there until 1775, when the American Revolutionary War began. During the war, Continental Army General George Washington used the mansion as his headquarters for about a month in 1776. After that, British and Hessian officers took over the house until 1783.

After the British left New York, the house had many different owners. It was even used as a tavern for a while. The Jumel family bought the house in 1810 and lived there off and on for many years. The house became a museum in 1907. It has been updated and cared for over the years.

The mansion's design mixes different styles like Federal, Georgian, and Palladian. It has a raised basement and three floors above ground. The front has a tall porch, and the back has a unique octagonal (eight-sided) room. Inside, you can find a kitchen, living rooms, and bedrooms. The museum displays furniture, decorations, and personal items from the people who lived there. The museum also hosts fun events and performances.

Contents

Exploring the Mansion's Location

The Morris–Jumel Mansion is at 65 Jumel Terrace in the Washington Heights neighborhood. It sits inside Roger Morris Park. The park is surrounded by Jumel Terrace, 160th Street, Edgecombe Avenue, and 162nd Street.

West of the mansion is Sylvan Terrace, which used to be the mansion's driveway. The area around the house has many homes, including some of Manhattan's last wooden houses. A subway station, the 163rd Street–Amsterdam Avenue station, is also nearby.

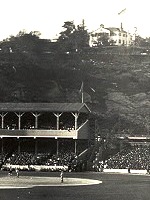

The mansion is on top of Coogan's Bluff, a high point. From here, people used to see amazing views of Lower Manhattan, the Hudson River, the Bronx, and other areas. The house also overlooked the Polo Grounds baseball stadium. People who lived there once claimed they could see seven counties from the house!

Roger Morris Park: The Mansion's Green Space

Roger Morris Park is a 1.52-acre park where the mansion is located. It is named after Roger Morris, who owned the land. This park is all that's left of his huge 130-acre estate. The mansion itself was built on one of the highest spots in Manhattan.

A gate on Jumel Terrace leads into the park. A brick path goes from the gate to the mansion's front door, lined with trees. There's also a stone wall on the east side of the park because the land slopes steeply.

In the park's northeast corner, you'll find a sunken garden. It was designed in the 1930s and has an octagonal shape, just like the mansion's back room. Stone paths divide the garden into sections. There are also grassy areas and a rose garden.

Who Lived Here? A Look at the Mansion's Past

The land where the mansion stands was once part of the town of Harlem in the 1600s. The first house on this spot was built around 1695. The land changed hands a few times before Roger Morris bought it in 1765.

The Morris Family's Time

Building a Dream Home

Roger Morris, a retired British Army officer, bought the land in 1765. At that time, the area was very rural, far from New York City's downtown. He wanted a quiet place where he could enjoy nature. He described it as a place where he "might find an eligible retreat for a gentleman fond of rural employments."

Construction started in mid-1765. Workers used oak trees from nearby forests to build the house. The house was first called Mount Morris. The Morris family also built a stable and carriage house. The entire estate was finished by 1770.

Roger and Mary Morris had two sons and two daughters while living here. Four enslaved people also lived in the house. The Morris family lived in the mansion until 1775, when the American Revolutionary War began. They were Loyalists, meaning they supported the British. Roger Morris went to England to protect his property. His family left the house by mid-1776.

George Washington's Headquarters

In September 1776, Continental Army General William Heath and his officers took over the house. Soon after, George Washington used the mansion as his headquarters for about a month. He arrived around September 14–15, 1776. The house was perfect because it was on a high hill, allowing Washington to see enemy troops approaching.

Washington stayed with his military secretary and aides, planning for the Battle of Harlem Heights. He reportedly watched the Great Fire of 1776 from the mansion's second-floor balcony. Washington's army retreated around October 21–22. British troops captured the nearby Fort Washington and took over the mansion on November 16, 1776.

The British occupied the house from 1776 until they left New York in 1783. British and Hessian commanders, like Lieutenant-General Henry Clinton and Baron Wilhelm von Knyphausen, used the mansion as their headquarters.

Changes After the Revolution (1780s-1800s)

After the war, the Morris family lost their estate because they were Loyalists. The house was sold in 1784. In 1785, it became a tavern called Calumet Hall. It was a popular stop for travelers on the Albany Post Road.

In 1790, after becoming U.S. President, George Washington returned to the house for a party with other important figures. He noted that the mansion was then "in the possession of a common farmer." The property changed owners several times over the next two decades. In 1809, John Jacob Astor, a very wealthy businessman, bought the property from the Morris heirs.

The Jumel Family's Era

In 1810, a French wine merchant named Stephen Jumel bought the house for $10,000. He moved in with his wife, Eliza Bowen Jumel, and their adopted daughter, Mary Bowen. The Jumels wanted to be part of New York City's high society.

Remodeling and Hosting Guests

The Jumels remodeled the house, adding a new entrance in the Federal style and redecorating the inside in the Empire style. Stephen Jumel wanted the renovation to impress people and help his wife gain social standing. They hosted many important European and American guests at their mansion.

The Jumels also owned other homes in Lower Manhattan and France. Mary Bowen, their adopted daughter, reportedly didn't like staying in the mansion alone because she believed it was haunted. The Jumels tried to sell the mansion in 1814 but couldn't.

In 1815, the Jumels went to France. Eliza returned to the mansion in 1817. During the 1820s, the mansion was rented out, mostly in the summer. Stephen Jumel gave Eliza ownership of the mansion and land in 1825. He returned to the U.S. in 1828. Stephen died in 1832 after a carriage accident.

Eliza Jumel's Later Years

In 1833, Eliza married former U.S. Vice President Aaron Burr in the mansion's parlor. Their marriage was short; Eliza filed for divorce in 1834, and it was granted in 1836, shortly before Burr's death. After this, Eliza was often alone in the mansion.

The house was sometimes rented out in the late 1830s. Eliza and the Chase family (related to Mary Bowen) moved back into the mansion by 1848. Eliza Jumel lived in the mansion until her death in 1865. In her final years, the mansion had few visitors and started to show its age.

After Eliza Jumel's Death

After Eliza died, her estate was involved in many lawsuits. The Chase family continued to live in the house for about 20 years. The legal disputes over the estate were finally settled in 1881. The mansion was put up for sale in 1882.

The Chase family stayed in the mansion until 1887, when they sold it. The house changed hands a few more times. The Earle family bought the mansion in 1894 and called it Earle Cliff. They made many changes to the inside and outside of the house. Lillie J. Earle, the new owner, hosted events for groups like the Children of the American Revolution at the mansion. The Earle family lived there until 1903.

The Mansion as a Museum

Becoming a Public Museum

By 1899, people started suggesting that New York City should buy the Jumel Mansion and turn it into a museum. Groups like the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society and the Daughters of the American Revolution supported this idea. The city decided to buy the house in 1903 for $235,000. Roger Morris Park opened to the public on December 28, 1903.

The Daughters of the American Revolution formed the Washington Headquarters Association (WHA) in 1904 to run the museum. After some disagreements with other groups, the WHA was allowed to operate the museum.

Opening and Early Years

The WHA planned to restore the Morris–Jumel Mansion to its original look. They wanted to fix old fireplaces and display furniture from the Jumel and Earle families. The museum officially opened on May 29, 1907.

In its early years, the museum attracted over 30,000 visitors annually. The Morris–Jumel Mansion was one of the few large old homes left in Washington Heights. It was easy to reach by subway and streetcar. In 1913, a new gateway was added to the mansion.

The museum's curator in the 1920s, William Henry Shelton, said many visitors came from the western and midwestern U.S. because there were few Revolutionary War sites there. The mansion was repainted and renovated in 1922.

Renovations and Visitors (1930s-Present)

In the 1930s, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks) started a major renovation with workers from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). They added a new stairway, pathways, and restored the basement kitchen to its 18th-century look. The house reopened in October 1936.

In the mid-1900s, the house was known by both the Morris and Jumel names. In 1945, the interiors were restored, with Morris family items on the first floor and Jumel family items on the second. The mansion became a National Historic Landmark in 1961 and a New York City Landmark in 1967. By then, rumors that the house was haunted had become popular.

By the 1970s, the museum had 20,000 visitors each year. Even British queen Elizabeth II visited the house in 1976 to celebrate the United States' 200th birthday. The house received a grant for preservation in 1987. The Morris–Jumel Mansion became a founding member of the Historic House Trust in 1989.

The mansion's exterior was extensively renovated starting in 1990. The project restored the house to its 19th-century appearance. By the late 1990s, the mansion was a popular stop for tourists. In the early 2000s, the house was repainted, and windows were replaced.

In 2013, an intern found a draft of the 1775 Olive Branch Petition in the attic. This important historical document was later sold to help raise money for the museum. In 2014, plans were made to raise money for more renovations and educational programs before the house's 250th anniversary.

The museum's popularity grew after the Broadway musical Hamilton opened in 2015. Many visitors came because of the musical. Eliza Jumel's bedroom and the parlor were restored in the early 2020s. In November 2021, funding was secured for another renovation. However, by late 2023, the house was still in need of major repairs, with paint peeling and parts of the porch collapsing.

Mansion's Design and Rooms

The Morris–Jumel Mansion is an early example of Palladian design in the U.S. It's not known who designed it, but Roger Morris might have designed his own home. The exterior was influenced by a 16th-century Italian architect named Palladio. The inside had a Georgian style. Later, the Jumels added Federal style elements around 1810.

The Morris–Jumel Mansion is the oldest house still standing in Manhattan. It's also the oldest building in Manhattan that is still technically used as a home, because a caretaker lives there.

Outside the Mansion

The mansion has two main parts. The main house is two and a half stories tall. At the back, there's a two-story octagonal (eight-sided) room, which might have been the first of its kind in the U.S. This octagonal part is connected to the main house by a short hallway.

The house was built with a wooden frame, but its outside walls are covered with white wooden siding that looks like stone. The corners of the house have decorative vertical blocks. The south side of the main house has a tall porch with large columns. This porch likely dates back to when the house was first built. It used to overlook New York Bay.

The front door is surrounded by fancy carvings. It has windows on the sides and a semicircular window above it, which the Jumel family added. Above the main entrance, on the second floor, there's a French door leading to a balcony. The house has a sloped roof with windows sticking out. There are three chimneys on the roof.

Inside the Mansion

The inside of the mansion covers about 12,000 square feet. It originally had a Georgian-style layout with wide main hallways. There were 19 rooms in total. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission says the house has "some of the finest Georgian interiors in America."

When the Morris–Jumel Mansion became a museum, it was filled with furniture and decorations that looked like what would have been there when the Morris, Washington, and Jumel families lived there. Today, it has nine restored rooms, including George Washington's office. You can also see the dining room and Eliza Jumel's bedroom, which has a bed supposedly owned by Napoleon. The museum also displays personal items from Morris, Washington, Jumel, and Aaron Burr.

Basement

The basement was dug out of solid rock. It used to have servants' bedrooms and the kitchen. In 1792, an advertisement mentioned a kitchen, laundry, wine cellar, and other rooms in the basement. Today, part of the basement is an apartment for the museum's caretaker.

The kitchen was very large for the 1760s, measuring 20 by 30 feet. It had a wooden floor and a plastered ceiling. A large brick fireplace was on the eastern wall.

First Floor

The main entrance leads into a central hallway. On either side of this hallway are two large rooms. To the left are the parlor and the library. The parlor was sometimes called the reception room. It has decorative window shutters, windows, and fancy moldings. There's also a fireplace with a wooden mantel. The library, at the back, has similar decorations.

To the right of the entrance hall is the dining room. This room is similar in style to the parlor. A wide archway in the dining room leads to a small alcove. The main staircase is also on this side of the house. The staircase has decorative steps and a handrail.

The octagonal drawing room at the back of the house is very special. It has paneled shutters, moldings, and many windows. George Washington once used this room as his headquarters. Later, Eliza Jumel would pretend to host royal guests here. Today, it is decorated with late-18th-century details, including Chinese wallpaper.

Second Floor

The second floor originally had seven bedrooms. The central part of this floor also has front and back hallways. The rooms on this floor were used as bedrooms. There's also a bedroom in the octagonal annex. After a renovation in 1945, these bedrooms were decorated with items belonging to Eliza Jumel, Mary Bowen, Aaron Burr, and George Washington.

The bedrooms are decorated similarly to the first-floor rooms, with fireplaces and decorative moldings. The southeastern bedroom was likely Eliza Jumel's, decorated in the Empire and Napoleonic styles. The southwestern bedroom probably belonged to Aaron Burr, and the northwestern one to Mary Bowen. The bedroom in the annex was used by Washington during the Revolutionary War.

Third Floor

The third floor was originally for guest bedrooms. In 1792, there were five such rooms. By 1916, there were only three. One of them, likely used by servants, had a fireplace without a mantel. Today, the third floor holds an archive and a reference library.

What You Can See and Do at the Museum

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation owns the Morris–Jumel Mansion. A non-profit organization called Morris–Jumel Mansion Inc. runs the museum. They work to keep the house open and to display its collections. The museum gets most of its money from grants, events, and admission fees.

The Museum's Collection

When the museum first opened, its collection included old sofas, lamps, and bed frames. It also had items from Revolutionary War soldiers' huts. In the 1920s, the museum displayed coins, guns, clothing, china, furniture, and a Bible that belonged to George Washington. There were also items from Eliza Jumel.

Over the years, the museum has added many more objects. These include a Masonic apron that might have belonged to Aaron Burr, and desks and chairs he used. By the 1940s, the rooms were filled with period furniture and mementos. Some items were borrowed from other museums or private collectors.

Today, the Morris–Jumel Mansion is still decorated with many objects used by the Morris, Washington, Jumel, and Burr families. The furniture collection includes pieces by famous designers like Thomas Sheraton and Thomas Chippendale. The house also has a porcelain collection, Eliza Jumel's bed, and French wallpapers.

Special Exhibits and Events

The museum often hosts temporary exhibits. In its early years, it displayed Revolutionary War objects and items made by women. In the 21st century, the museum regularly presents new exhibits, such as one on the house's history in 2009 and historical portraits of Washington Heights in 2022.

The museum has always hosted events. In the early 1900s, there were annual lawn parties and Washington's Birthday celebrations. They also had lectures and meetings. In the mid-1900s, they held Flag Day ceremonies and Revolutionary War reenactments.

Today, the mansion regularly hosts lectures, concerts, and special exhibits. Past events include plays about Eliza Jumel's life, music festivals, and Easter egg hunts. They also have outdoor jazz concerts and suppers with food from the Founding Fathers' time.

One popular program is the ghost tours and "paranormal investigations." This is because the mansion is rumored to have up to five ghosts, including those of Aaron Burr and Eliza Jumel! The museum also has monthly Family Day events and online "parlor chats." They offer workshops, plays, and art shows.

Why the Mansion is Important

The Morris–Jumel Mansion has been recognized for its importance for a long time. In 1881, The New York Times called it a unique house. In 1885, The Washington Post said it looked much younger than its age because it was often repainted.

Many people have praised the mansion's design and history. An architect named William F. Lamb, who helped design the Empire State Building, called the mansion "one of the most impressive sights in New York." A writer for The Spur said in 1936 that visiting the house felt like stepping back in time. The jazz musician Duke Ellington, who lived nearby, called the mansion "the Crown of Sugar Hill."

The museum's collections have also received positive comments. The New York Daily News said in 1968 that the furnishings showed Eliza Jumel's lifestyle. The Wall Street Journal called the mansion one of "Manhattan's sometimes overlooked cultural gems" in 2014.

Special Landmark Status

The mansion's historical importance was recognized early on. It was photographed by the New York City Art Commission in 1914. It became a National Historic Landmark in 1961, making it one of the first buildings to receive this honor. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

The exterior of the Morris–Jumel Mansion was named a New York City Landmark in 1967. In 1970, it became part of the Jumel Terrace Historic District. In 1975, the first and second floors of the mansion's interior were also designated as landmarks.

Featured in Media

The house has appeared in popular media for a long time. It reportedly inspired a mansion in James Fenimore Cooper's 1821 novel The Spy. In 1996, the Morris–Jumel Mansion was featured in Bob Vila's Guide to Historic Homes of America. The TV show Ghost Adventures filmed an episode there in 2014.

Most famously, Lin-Manuel Miranda wrote parts of his hit musical Hamilton at the Morris–Jumel Mansion in 2015. The TV show Broad City also filmed a scene at the mansion in 2019.

The house has also been part of other exhibits. It was featured in a 1952 exhibition of old New York City houses. Over the years, the mansion has been the subject of several historical studies, including a book by William Henry Shelton in 1916.

See also

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan above 110th Street

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- List of Washington's Headquarters during the Revolutionary War

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan above 110th Street

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |