Continental Army facts for kids

The Continental Army was the main army for the thirteen American colonies. They fought against Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. This army was officially created by the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775.

Most of the Continental Army was disbanded on November 3, 1783. This happened after the Treaty of Paris ended the war. A small group of soldiers stayed at West Point. Later, on June 3, 1784, Congress created the United States Army. This new army still exists today.

Contents

How the Continental Army Started

On June 7, 1775, the Continental Congress decided to create a united army. This army was for the common defense of the colonies. At first, only twelve colonies were represented. Georgia joined later.

The Congress chose the soldiers already gathered in Cambridge, Massachusetts. These became the first units of the Continental Army. On June 15, they voted to make George Washington their commander-in-chief. Washington accepted the job without pay. He only asked for his expenses to be covered.

Soon after, four major-generals and eight brigadier-generals were appointed. These leaders helped organize the new army.

Changes to the Army Over Time

The Continental Army changed a lot during the war. Americans generally did not want a large, permanent army. But fighting the British needed a strong, organized military. So, the army was often officially dissolved and then reorganized.

The Continental Army went through several main phases:

- The Continental Army of 1775: This was the first army, mostly from New England. Washington organized it into three divisions. Some soldiers also went to invade Canada.

- The Continental Army of 1776: This army was reorganized after the first soldiers' enlistments ended. Washington suggested changes, but they took time to happen. This army was still mostly from the Northeast.

- The Continental Army of 1777 - 1780: Big changes happened here. The British sent many soldiers to end the revolution. Congress ordered each state to provide soldiers based on its population. Washington also got permission to raise more battalions. Soldiers began enlisting for three years or until the war ended. This helped avoid yearly shortages of troops.

- The Continental Army of 1781 - 1782: This was a very tough time for the Americans. Congress had almost no money. It was hard to get new soldiers when old enlistments ran out. Support for the war was low. Washington even had to stop mutinies (rebellions) among his soldiers. Congress cut army funding, but Washington still won important battles.

- The Continental Army of 1783 - 1784: As peace with Britain was agreed upon, most regiments were disbanded. This army was later replaced by the United States Army.

Besides the Continental Army, local militia groups also fought. These were raised and paid for by individual colonies or states.

States were supposed to pay, feed, clothe, and arm their soldiers. But how well they did this varied. The army often faced money problems and low morale as the war continued.

How the Army Became Stronger

In June 1775, the army in Cambridge had about 16,000 men from New England. Artemas Ward was in command. John Thomas was his executive officer. Richard Gridley led the artillery and was the chief engineer.

The British army in Boston was growing. They had about 10,000 soldiers. Generals Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne joined General Thomas Gage. They planned to defeat the American rebels. With these experienced officers and soldiers, and British ships nearby, Governor Gage declared martial law. He called the Continental Army and its supporters "rebels." He offered forgiveness to those who stopped supporting the American cause. However, Samuel Adams and John Hancock were still wanted for treason. This proclamation only made the Americans more determined.

Throughout the war, the army faced many problems. They had poor supplies, not enough training, and soldiers often enlisted for short times. States also argued with each other. Congress struggled to make states provide food, money, or supplies. At first, soldiers joined for a year, driven by patriotism. But as the war went on, rewards and other incentives became common. Two major mutinies greatly weakened some units. Discipline was a constant challenge.

The army improved its fighting skills through many difficult experiences. General Washington and other officers were key leaders. They helped keep the army united, learn from mistakes, and maintain discipline for eight years. Washington always saw the army as a temporary group. He worked hard to keep the military under civilian control.

Washington resigned his position when the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783. This treaty ended the war and confirmed America's independence. Washington willingly giving up power was very important. Many people might have wanted him to become a king. But his choice helped prevent a military dictatorship and ensured that democracy would grow in the United States.

After the war, the officers formed the Society of the Cincinnati in May 1783. They chose George Washington as their first President. He served until his death in 1799. The Society is still active today. It includes descendants of the original officers from America and France.

Major Battles

- Siege of Boston

- Battle of Long Island

- Battle of Trenton

- Battle of Princeton

- Battle of Saratoga

- Battle of Yorktown

Images for kids

-

1778 drawing showing a Stockbridge Mahican Indian, Patriot soldier, of the Stockbridge Militia, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, from the Revolutionary War diary of Hessian officer, Johann Von Ewald

-

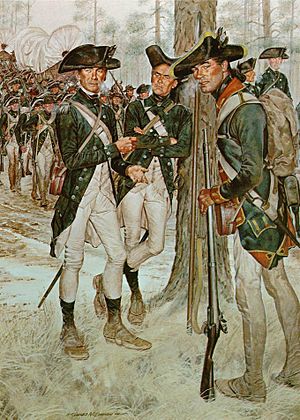

1781 drawing of American soldiers from the Yorktown campaign showing a black infantryman, on the far left, from the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, one of the regiments in the Continental Army having the largest majority of black patriot soldiers. An estimated 4% of the Continental Army was black (see African Americans in the Revolutionary War).

-

Continental Army Plaza, Williamsburg, Brooklyn

-

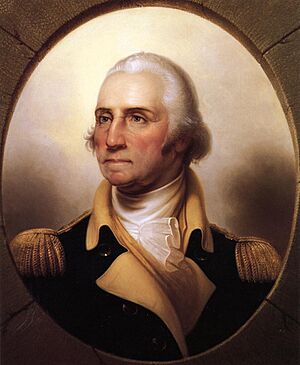

Aide-de-camp, General Washington, Major-general Artemas Ward.

See also

In Spanish: Ejército Continental para niños

In Spanish: Ejército Continental para niños