Samuel Adams facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Adams

|

|

|---|---|

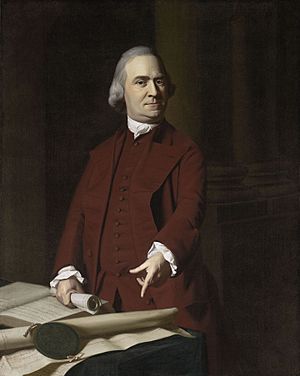

In this c. 1772 portrait by John Singleton Copley, Adams points at the Massachusetts Charter, which he viewed as a constitution that protected the peoples' rights.

|

|

| 4th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office October 8, 1794 – June 2, 1797 |

|

| Lieutenant | Moses Gill |

| Preceded by | John Hancock |

| Succeeded by | Increase Sumner |

| 3rd Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office 1789–1794 Acting Governor October 8, 1793 – 1794 |

|

| Governor | John Hancock |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Lincoln |

| Succeeded by | Moses Gill |

| President of the Massachusetts Senate | |

| In office 1787–1788 1782–1785 |

|

| Delegate from Massachusetts to the Continental Congress | |

| In office 1774–1777 |

|

| In office 1779–1781 |

|

| Clerk of the Massachusetts House of Representatives | |

| In office 1766–1774 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 27 [O.S. September 16] 1722 Boston, Massachusetts Bay |

| Died | October 2, 1803 (aged 81) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Granary Burying Ground, Boston |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (1790s) |

| Spouses |

Elizabeth Checkley

(m. 1749; died 1757)Elizabeth Wells

(m. 1764) |

| Alma mater | Harvard College |

| Signature | |

Samuel Adams (September 27 [O.S. September 16] 1722 – October 2, 1803) was an important American statesman and thinker. He was one of the Founding Fathers who helped create the United States.

Contents

- Samuel Adams' Early Life

- Samuel Adams' Early Career

- The Stamp Act Protests

- The Townshend Acts and Boycotts

- Boston Under British Control

- The Boston Tea Party

- The Road to Revolution

- The First Continental Congress

- The Second Continental Congress

- Later Life and Death

- Samuel Adams' Legacy

- Samuel Adams' Personal Life

- Interesting Facts About Samuel Adams

- Samuel Adams Quotes

- See also

Samuel Adams' Early Life

Samuel Adams was born in Boston on September 16, 1722. He was one of twelve children. His parents were Samuel Adams, Sr., and Mary (Fifield) Adams. The family lived on Purchase Street in Boston.

His father, Samuel Adams, Sr. (1689–1748), was a successful merchant. He was also a church deacon and later served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives.

Young Samuel Adams went to Boston Latin School. Then, in 1736, he started at Harvard College. He graduated in 1740 and earned a master's degree in 1743.

Samuel Adams' Early Career

After finishing his studies at Harvard in 1743, Adams tried to start a business. His father lent him a lot of money, but Adams lost it. He lent half to a friend who never paid him back. He spent the other half.

After this, his father made him a partner in the family's malthouse. When his father died in 1748, Samuel Adams took over the family's business.

Like his father, Adams became involved in politics. He quickly became a well-known person in Boston. Before and during the American Revolution, Adams used colonial newspapers. He wrote articles in the Boston Gazette to promote the idea of colonial rights. He openly criticized British rules and pushed for independence from Britain. Adams often used different pen names, like "Candidus" or "Vindex."

The Stamp Act Protests

After Britain won the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the British government was deeply in debt. To raise money, the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765. This law made colonists pay a new tax on most printed materials. This included newspapers, legal documents, and playing cards.

The Stamp Act caused a huge outcry in the colonies. Adams argued that the Stamp Act was unfair and against their rights. He supported calls to stop buying British goods. This was a way to pressure Parliament to cancel the tax. In Boston, a group called the Loyal Nine, which later became the Sons of Liberty, organized strong protests against the Stamp Act.

The Stamp Act was supposed to start on November 1, 1765. But it was never truly put into action. Protesters across the colonies forced the tax collectors to quit. British merchants, losing money from the boycotts, convinced Parliament to repeal the tax. News of the repeal reached Boston by May 16, 1766. There were big celebrations, and Adams publicly thanked the British merchants.

The Townshend Acts and Boycotts

After the Stamp Act was canceled, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts in 1767. These laws put new taxes (called duties) on goods imported into the colonies. These goods included glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea. The money from these taxes would pay for governors and judges. This meant these officials would not depend on the colonists for their salaries.

To make sure the new laws were followed, the Townshend Acts created a new customs agency. It was called the American Board of Custom Commissioners and was based in Boston.

Adams used the Boston Town Meeting to organize a boycott of British goods. He urged other towns to do the same. By February 1768, towns in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut had joined the boycott.

In January 1768, the Massachusetts House of Representatives sent a letter to King George III asking for his help. Adams insisted that the House also send this letter to other colonies. This letter became known as the Massachusetts Circular Letter. It asked the colonies to join Massachusetts in resisting the Townshend Acts.

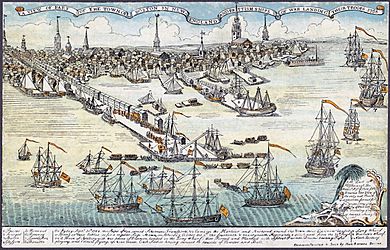

Customs officials in Boston found it hard to enforce the new trade rules. They asked for military help. The warship HMS Romney arrived in Boston Harbor in May 1768. The situation became tense on June 10. Customs officials seized Liberty, a ship owned by John Hancock. He was a strong critic of the customs board. A riot broke out when soldiers tried to tow the Liberty away. Customs officials became scared and fled to a fort in the harbor.

Governor Bernard wrote to London, saying that troops were needed in Boston to restore order. Lord Hillsborough then ordered four regiments of the British Army to Boston.

Boston Under British Control

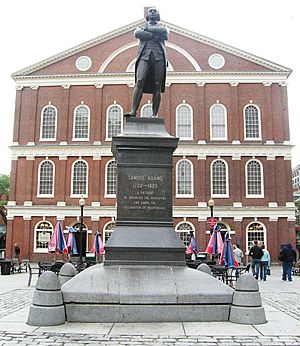

When Bostonians learned that British troops were coming, the Boston Town Meeting gathered on September 12, 1768. They asked Governor Bernard to call a meeting of the General Court. Bernard refused. So, the town meeting asked other Massachusetts towns to send representatives to meet at Faneuil Hall on September 22. About 100 towns sent delegates to this convention. It was like an unofficial meeting of the Massachusetts House.

The convention sent a letter saying that Boston was not lawless. They said the military occupation violated Bostonians' natural and constitutional rights. By the time the convention ended, British troop ships had arrived. Two regiments landed in October 1768, and two more in November.

Many people believe the occupation of Boston was a turning point for Adams. He wrote many letters and essays against the occupation. He saw it as a violation of the 1689 Bill of Rights. Adams continued to work to get the troops removed and to keep the boycott going. He wanted the Townshend duties to be canceled. Two regiments left Boston in 1769, but two stayed.

Tensions between soldiers and civilians grew. This led to the Boston Massacre in March 1770, where five civilians were killed. After the Boston Massacre, Adams and other town leaders met with Governor Thomas Hutchinson. They demanded that the troops leave. The situation was very tense, so the army commander agreed to move both regiments to a fort called Castle William.

The Boston Tea Party

In May 1773, the British Parliament passed the Tea Act. This law was meant to help the struggling East India Company. This company was very important to Britain. Because of high taxes in Britain, people there bought smuggled Dutch tea. This was cheaper than the East India Company's tea. So, the company had a huge amount of tea it couldn't sell.

The British government decided to sell this extra tea in the colonies. The Tea Act allowed the East India Company to send tea directly to the colonies. This meant they could skip most of the merchants who used to sell the tea. This threatened the American colonial economy. The company could sell tea much cheaper than local merchants or even smugglers. The act also kept the unpopular Townshend tax on tea imported into the colonies. In late 1773, seven ships carrying East India Company tea were sent to the colonies, with four headed for Boston.

News of the Tea Act caused a huge wave of protests. Colonial smugglers were especially upset. The Tea Act made legal tea cheaper, which threatened their business of selling smuggled Dutch tea.

Adams and the correspondence committees encouraged people to oppose the Tea Act. The tea ship Dartmouth arrived in Boston Harbor in late November. Adams wrote a letter calling for a large meeting at Faneuil Hall on November 29. So many people came that the meeting moved to the larger Old South Meeting House. British law said the Dartmouth had to unload its tea and pay taxes within twenty days. If not, customs officials could take the cargo. The meeting passed a resolution, suggested by Adams. It asked the captain of the Dartmouth to send the ship back without paying the tax. Meanwhile, twenty-five men were assigned to watch the ship and stop the tea from being unloaded.

Governor Hutchinson refused to let the Dartmouth leave without paying the tax. Two more tea ships, the Eleanor and the Beaver, arrived. The fourth ship, the William, got stuck near Cape Cod and never reached Boston. December 16 was the last day for the Dartmouth's deadline. About 7,000 people gathered around the Old South Meeting House. Adams heard that Governor Hutchinson had again refused to let the ships leave. He announced, "This meeting can do nothing further to save the country."

According to a popular story, Adams's statement was a secret signal for the "tea party" to begin. However, this story appeared much later. It seems Adams was actually trying to keep the meeting going.

While Adams tried to regain control of the meeting, people left the Old South Meeting House and headed to Boston Harbor. That evening, a group of 30 to 130 men boarded the three ships. Some were dressed as Mohawk Indians. Over three hours, they dumped all 342 chests of tea into the water. Adams never said if he went to the wharf to see it. It's not known if he helped plan the event. But Adams immediately worked to tell people about it and defend it. He argued that the Tea Party was not a lawless act. He said it was a principled protest and the only way people could defend their rights.

The Road to Revolution

In 1774, Great Britain responded to the Boston Tea Party with the Coercive Acts. The first act, the Boston Port Act, closed Boston's port. It would stay closed until the East India Company was paid back for the destroyed tea. The Massachusetts Government Act changed the Massachusetts Charter. It made many officials appointed by the King, not elected. It also greatly limited town meetings. The Administration of Justice Act allowed colonists accused of crimes to be tried in another colony or in Great Britain. A new royal governor, General Thomas Gage, was appointed to enforce these acts. He was also the commander of British military forces in North America.

Adams worked to organize resistance against the Coercive Acts. In May 1774, the Boston Town Meeting, with Adams leading it, organized a boycott of British goods. In June, Adams led a committee in the Massachusetts House. They suggested that an inter-colonial congress meet in Philadelphia in September. Adams was one of five delegates chosen to attend the First Continental Congress.

The First Continental Congress

On September 16, Paul Revere brought the Suffolk Resolves to Congress. These were resolutions from Massachusetts promising strong resistance to the Coercive Acts. Congress supported the Suffolk Resolves. They also issued a Declaration of Rights. This declaration said Parliament had no right to make laws for the colonies. They also organized a colonial boycott called the Continental Association.

Adams returned to Massachusetts in November 1774. He served in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. This Congress created the first minutemen companies. These were militiamen ready for action at a moment's notice. Adams also led the Boston Town Meeting, even though the Massachusetts Government Act tried to stop it. He was appointed to a committee to enforce the Continental Association. He was also chosen to attend the Second Continental Congress, which was set to meet in Philadelphia in May 1775.

The Second Continental Congress

The Continental Congress kept its discussions secret. So, Adams's exact role in all the talks is not fully known. He served on many committees, often dealing with military matters. One of his most famous actions was nominating George Washington to be the commander in chief of the Continental Army.

After the Declaration of Independence, Congress continued to manage the war. Adams served on military committees. In 1777, he was appointed to the Board of War. He supported giving bonuses to Continental Army soldiers. This was to encourage them to stay in the army for the whole war. He also wanted strict laws to punish Loyalists. These were Americans who still supported the British King. Adams believed they were as dangerous as British soldiers. In Massachusetts, over 300 Loyalists were sent away, and their property was taken. After the war, Adams did not want Loyalists to return to Massachusetts. He feared they would try to weaken the new republican government.

Adams was the Massachusetts delegate chosen for the committee to write the Articles of Confederation. This was the first plan for how the colonies would be united. Adams signed the Articles of Confederation with the other Massachusetts delegates in 1778. But all the states didn't approve them until 1781.

In 1779, Adams returned to Boston for a state constitutional convention. The Massachusetts General Court had suggested a new constitution the year before, but voters rejected it. So, a convention was held to try again. Adams was on a three-person committee to write the new constitution. His cousin John Adams and James Bowdoin were also on the committee. They wrote the Massachusetts Constitution. It was changed a bit by the convention and approved by voters in 1780. This new constitution set up a republican government. It had yearly elections and a separation of powers.

In 1781, Adams left the Continental Congress. He returned to Boston and never left Massachusetts again.

Later Life and Death

When he returned to Massachusetts, Adams led the Boston Town Meeting. He was also elected to the state senate. In 1787, delegates met at the Philadelphia Convention. They were supposed to update the Articles of Confederation. But instead, they created a new United States Constitution. This new plan created a much stronger national government. Adams was one of the "Anti-Federalists" who worried about a strong national government. But he was elected to the Massachusetts ratifying convention in January 1788.

In 1789, Adams was elected Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts. He served until Governor Hancock died in 1793. Then, Adams became acting governor. The next year, Adams was elected as governor on his own. He served four one-year terms.

Adams played a big part in getting Boston to provide free public education for children, even for girls. He was also one of the first members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Samuel Adams retired from politics in 1797. He passed away at age 81 on October 2, 1803. He was buried at the Granary Burying Ground in Boston.

Samuel Adams' Legacy

People who lived at the same time as Adams saw him as one of the most important leaders of the American Revolution. Thomas Jefferson called Adams "truly the Man of the Revolution." Leaders in other colonies were compared to him. For example, Cornelius Harnett was called the "Samuel Adams of North Carolina."

Adams's name is used by two non-profit groups: the Sam Adams Alliance and the Sam Adams Foundation. These groups use his name to honor his skill in organizing citizens at the local level to achieve a national goal.

Samuel Adams' Personal Life

In October 1749, Adams married Elizabeth Checkley, his pastor's daughter. Elizabeth had six children over seven years. But only two lived to be adults: Samuel (born 1751) and Hannah (born 1756). Only Hannah married and had children. All of Samuel Adams's known descendants come from her.

Samuel Adams, Jr. died at just 37 years old. He had been a surgeon in the Revolutionary War. He got sick and never fully recovered. His death was a huge blow to the elder Adams. The younger Adams left his father money he had earned as a soldier. This gave Adams and his wife financial security in their later years. Investments in land made them quite wealthy by the mid-1790s. But they still lived a simple life.

In July 1757, Elizabeth died after giving birth to a baby who did not survive. Adams married again in 1764 to Elizabeth Wells. They did not have any children together.

Interesting Facts About Samuel Adams

- Adams was a second cousin to President John Adams.

- Adams's parents were very religious Puritans. Adams was proud of his Puritan background. He often talked about Puritan values in his political work, especially virtue (being good and honest). He believed that if leaders were not virtuous, freedom would be in danger.

- In 1756, the Boston Town Meeting elected Adams as a tax collector. He often failed to collect taxes from his fellow citizens. This meant he was responsible for the missing money. By 1765, he owed over £8,000. Adams had to sue people who didn't pay taxes, but many taxes were still not collected. In 1768, his political opponents used this against him. They got a court order for him to pay £1,463. Adams's friends paid some of the debt, and the town meeting canceled the rest.

- Adams could not afford the trip to attend the First Continental Congress. So, his friends bought him new clothes and paid for his journey to Philadelphia.

- Adams suffered from a movement disorder called essential tremor. This made it hard for him to write in the last ten years of his life.

Samuel Adams Quotes

- "We cannot make events. Our business is wisely to improve them."

- "Mankind are governed more by their feelings than by reason."

- "It is in the interest of tyrants to reduce the people to ignorance and vice. For they cannot live in any country where virtue and knowledge prevail."

- "All might be free if they valued freedom, and defended it as they should."

- "Among the natural rights of the colonists are these: First a right to life, secondly to liberty, and thirdly to property; together with the right to defend them in the best manner they can."

See also

In Spanish: Samuel Adams para niños

In Spanish: Samuel Adams para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |