Thomas Hutchinson (governor) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Hutchinson

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Edward Truman, 1741

|

|

| 12th Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office 14 March 1771 – 17 May 1774 |

|

| Lieutenant | Andrew Oliver |

| Preceded by | Himself (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Gage |

| Acting Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office 3 June 1760 – 2 August 1760 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Pownall |

| Succeeded by | Francis Bernard |

| In office 2 August 1769 – 14 March 1771 |

|

| Preceded by | Francis Bernard |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as governor) |

| Lieutenant Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office 1758 – 14 March 1771 |

|

| Preceded by | Spencer Phips |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Oliver |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 September 1711 Boston, Massachusetts Bay British America |

| Died | 3 June 1780 (aged 68) Brompton, Middlesex Great Britain |

| Political party | Loyalist |

| Spouses |

Margaret Sanford

(m. 1732; died 1754) |

| Children | 12 (5 survived to adulthood) |

| Profession | politician, businessman |

| Signature | |

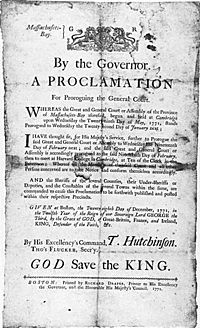

Thomas Hutchinson (born September 9, 1711 – died June 3, 1780) was an important businessman, historian, and politician in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. He was a strong Loyalist, meaning he supported British rule, during the years leading up to the American Revolution. Many people saw him as the most important Loyalist leader in Massachusetts before the war.

Hutchinson was a very successful merchant and worked in high positions in the Massachusetts government for many years. He served as lieutenant governor and then governor from 1758 to 1774. Even though he first disagreed with new British tax laws, he became a target for people like John Adams and Samuel Adams, who saw him as a supporter of unpopular British taxes.

In 1765, during protests against the Stamp Act, angry crowds attacked Hutchinson's home. In 1770, as acting governor, he faced angry mobs after the Boston Massacre. He ordered British troops to leave Boston for Castle William. Later, in 1773, some of his private letters were published. In these letters, he seemed to suggest that colonists' rights should be limited, which made people dislike him even more.

In May 1774, General Thomas Gage replaced Hutchinson as governor. Hutchinson then moved to England, where he advised the British government on how to handle the American colonists. He was very interested in history and wrote a three-volume book called History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The last volume, published after he died, covered his own time in office.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Thomas Hutchinson was born on September 9, 1711, in the North End of Boston. He was the fourth of twelve children born to Thomas and Sarah Foster Hutchinson. His family had been in New England for a long time, and he was related to early settlers like Anne Hutchinson. Both his parents came from wealthy merchant families. His father was involved in business and also in politics and charity work.

Young Thomas started Harvard College when he was twelve and finished in 1727. His father taught him about business early, and he was very good at it. He once turned a small gift of "five quintals of fish" (about 500 pounds of fish) from his father into a lot of money by the time he was 21.

In 1734, he married Margaret Sanford. Her grandfather was Governor Peleg Sanford of Rhode Island. The Sanford and Hutchinson families had many business and personal connections. Thomas and Margaret had twelve children, but only five lived to be adults. Margaret died in 1754 after childbirth.

Becoming a Leader

In 1737, Hutchinson started his political career. He was first elected as a Boston selectman and then to the Massachusetts General Court (the local assembly). He spoke out against the province printing too much paper money, which caused prices to rise and hurt the economy. This idea was not popular with everyone, and he lost his election in 1739.

He then went to England to represent landowners who were affected by a decision about the border between Massachusetts and New Hampshire. His trip wasn't successful for the border issue, but he did return with money for Harvard to build a new chapel, which is now Holden Chapel.

In 1742, Hutchinson was elected to the General Court again and served until 1749. He was the speaker of the assembly from 1746 to 1749. He kept pushing for money reforms, which made some people so angry that he needed guards for his homes in Boston and Milton.

When the British government repaid Massachusetts for its costs in the 1745 Louisbourg expedition, Hutchinson suggested using the large payment (about £180,000 in gold and silver) to get rid of the paper money. Even though many people were against it, he successfully passed a bill in 1749. Many opponents were surprised when exchanging paper money for gold and silver didn't cause problems, and Hutchinson became very popular.

After leaving the assembly in 1749, he was immediately appointed to the Governor's Council. He also worked on treaties with Native Americans and settled border disputes. In 1752, he became a judge. When the French and Indian War started in 1754, he attended the Albany Congress. There, he worked with Benjamin Franklin to create a plan for the colonies to unite. Hutchinson believed the colonies needed to work together against their common enemy.

Hutchinson's wife died in 1754, and he focused even more on his work. He also helped Acadian refugees who had been forced out of their homes in Nova Scotia. He also supported military families during the war.

Lieutenant Governor

In 1758, Hutchinson was appointed lieutenant governor, serving under Governor Thomas Pownall. Their relationship was difficult because Pownall had helped remove the previous governor, William Shirley, whom Hutchinson had supported. Pownall often tried to get Hutchinson to turn against Shirley's supporters, which Hutchinson refused to do. Pownall left in 1760, leaving Hutchinson as acting governor. A few months later, Francis Bernard arrived as the new governor.

Writs of Assistance and Taxes

One of Governor Bernard's first actions was to appoint Hutchinson as Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court. This angered many people, especially James Otis Sr. and his son James Otis Jr., who had hoped Otis Sr. would get the job. Hutchinson had no legal training and hadn't asked for the job.

In 1761, Hutchinson caused more anger by issuing writs of assistance. These documents allowed customs officials to search homes and businesses without a specific reason. Even though some had been issued before, Hutchinson's actions led to strong protests. John Adams and the Otises used this issue to criticize Hutchinson, saying he had too much power and wasn't qualified.

When the Sugar Act was being discussed in England in 1763, Hutchinson agreed with people like James Otis Jr. that the law would hurt Massachusetts' economy. However, they disagreed on whether the British Parliament had the right to tax the colonies. The anti-Parliament group, led by James Otis Jr. and Oxenbridge Thacher, used every small disagreement to criticize Hutchinson. Hutchinson at first didn't think these attacks were serious, but they slowly built strong opposition against British control and damaged his reputation.

Before the Stamp Act was passed in 1765, both Hutchinson and Governor Bernard quietly warned London not to pass it. Hutchinson wrote that "It cannot be good to tax the Americans ... You will lose more than you gain." However, when the Massachusetts assembly met to protest the act, Hutchinson pushed for a more moderate statement. This made the Massachusetts protest seem weak compared to other colonies, and people accused Hutchinson of secretly supporting the Stamp Act. He was even called a "traitor."

Mob Violence and Protests

Hutchinson's brother-in-law, Andrew Oliver, was given the job of "stamp master," meaning he was in charge of carrying out the Stamp Act in Massachusetts. Even though Hutchinson likely had nothing to do with this, his opponents quickly accused him of being dishonest.

On August 13, 1765, angry crowds attacked Oliver's home and office. The next night, a crowd surrounded Hutchinson's Boston home. They demanded he publicly deny supporting the Stamp Act. He refused.

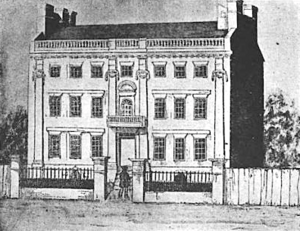

Twelve days later, on August 26, a mob again gathered outside his home. This time, they broke in. Hutchinson and his family barely escaped. The mob systematically destroyed his beautiful house, ruining the inside and even taking down the cupola (a small dome on the roof). They stole or destroyed his silver, furniture, and other belongings. His valuable collection of historical documents was scattered, and many pages of his history book were lost. Hutchinson and his family had to find safety at Castle William. He later received over £3,100 from the province for the damage.

Governor of Massachusetts

After the Stamp Act protests, the radical group gained control of the assembly and the governor's council in 1766. Hutchinson was not allowed a seat on the council. After the Townshend Acts were passed in 1767, Governor Bernard asked for British troops to protect royal officials. Bernard's letters describing the situation were published by the opposition, leading to his recall. Bernard left for England on August 1, 1769, making Hutchinson acting governor. Hutchinson tried to distance himself from Bernard, but he was still attacked by the assembly and newspapers. He continued to push for a formal appointment as governor.

Hutchinson was still acting governor during the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, when British soldiers fired into a crowd, killing five people. Hutchinson went to the scene and promised fair justice. He had the soldiers arrested the next day. However, ongoing unrest forced him to ask for the British troops to be moved out of the city to Castle William. The soldiers were later tried, and two were found guilty of manslaughter. This event made Hutchinson doubt his ability to manage things in the province, and he wrote a letter of resignation.

Meanwhile, Governor Bernard had been supporting Hutchinson in London. In March 1771, Hutchinson's official appointment as governor arrived in Boston. The instructions that came with his appointment were strict, giving him little room to make political decisions. One instruction that particularly angered Samuel Adams was to move the assembly meetings from Boston to Cambridge. This was meant to reduce the influence of radical Boston politics.

This move caused huge complaints from the assembly, leading to thousands of pages of arguments between Hutchinson and the assembly until 1772. The radicals used this to show Hutchinson was trying to take away their rights. They were even more upset when Hutchinson announced in 1772 that his salary would be paid by the British Crown instead of by the assembly. This was seen as another attempt to take power away from the province.

Letters and the Tea Party

The debate in Massachusetts became very intense in 1772. Hutchinson argued that the colony was either fully under Parliament's control or it was completely independent. The assembly, led by John Adams, Samuel Adams, and Joseph Hawley, replied that their colonial charter gave them self-rule.

In England, colonial agent Benjamin Franklin got hold of some letters written by Hutchinson and other officials in the late 1760s. Franklin believed these letters showed that Hutchinson had misrepresented the situation in the colonies to Parliament. Hoping to turn colonial anger away from Parliament, Franklin sent the letters to Thomas Cushing, the speaker of the Massachusetts assembly, in December 1772. He asked that they not be published. However, the letters ended up with Samuel Adams, who arranged for them to be published in June 1773. The publication caused a huge outcry against Hutchinson, but it did not lessen the opposition to Parliament. Instead, people saw the letters as proof of a plot against their rights. Hutchinson was even burned in effigy (a dummy made to look like him was burned) in other colonies.

Hutchinson's letters, written to Thomas Whately, a former British government official, included the idea that colonists couldn't have all the same rights as people in England. He suggested that some "English liberties" might need to be limited. While much of what Hutchinson wrote wasn't new, Samuel Adams skillfully used parts of the letters to make it seem like Hutchinson was conspiring with London officials to take away colonial rights.

The Massachusetts assembly asked for Hutchinson to be removed from office. Hutchinson asked to go to England to defend himself. He left for England on June 1, 1774, believing he would only be away for a short time.

In the meantime, Parliament had passed the Tea Act, which allowed the British East India Company to ship tea directly to the colonies. This cut out colonial merchants and made smuggled Dutch tea more expensive. This caused merchants across the colonies to protest. In Massachusetts, when tea ships arrived in November 1773, Hutchinson refused to let them leave the harbor without the tea being unloaded and the tax paid. On December 16, protestors, some dressed as Native Americans, boarded the ships and dumped the tea into the harbor.

Hutchinson defended his strict actions, saying it was his duty to uphold the law. However, critics argued he could have simply refused the tea shipments. After the Boston Tea Party, Parliament passed the "Coercive Acts" to punish Massachusetts. General Thomas Gage arrived in Boston in May 1774 to take over as governor and enforce these new laws.

Exile in England

When Hutchinson arrived in London, he met with the King and was well-received by other British leaders. He expressed his concern about the new laws for Massachusetts, especially the one that hurt Boston's economy. However, by 1774, events had gone too far for the British government to consider other options.

When the American Revolutionary War began in April 1775, Hutchinson's home in Milton was taken over by the army. A trunk with many of his letters fell into the hands of the rebels. As the war continued, Hutchinson was criticized by some British politicians. He continued to be favored by the King but lost most of his money due to his exile. He was forced to refuse an offer of a baronetcy (a title of honor).

On July 4, 1776, Hutchinson received an honorary degree from Oxford University. His enemies in Massachusetts continued to attack his reputation, and he couldn't defend himself from England. His properties in Massachusetts, like those of other exiled Loyalists, were taken and sold by the state. His Milton home was eventually bought by James and Mercy Otis Warren (Mercy was the sister of his old enemy, James Otis, Jr.).

Hutchinson was sad and disappointed about being forced to leave his home. He also grieved the loss of his daughter Peggy in 1777. He continued to work on his history of the colony. The first two volumes were published during his lifetime, and the third, covering his time as governor, was published after he died. He also worked on a history of his own family.

Thomas Hutchinson died in Brompton, London, on June 3, 1780, at the age of 68. He was buried in Croydon Minster in south London.

Legacy and Memory

Because he was a main target for those who opposed British rule, Hutchinson's reputation in America was generally very bad. He was often seen as a traitor to Massachusetts and to the idea of freedom. John Adams, for example, called him greedy and a "courtier" who manipulated powerful people for his own goals. British politicians also criticized him.

However, historians in the 20th century have started to look at his reputation differently. They try to explain why he was seen so negatively. Today, historians often describe Hutchinson as a sad figure caught between his rulers in London and the people of Massachusetts. Some say he was a "victim of the clash of two ideologies" – his own older way of thinking versus the new, modern ideas of his opponents.

Parts of Hutchinson's country estate in Milton have been saved. A piece of land called Governor Hutchinson's Field is now owned by The Trustees of Reservations and is open to the public. Nearby, you can see a ha-ha, a special type of hidden fence, built for Hutchinson in 1771. In Boston, landmarks named after the Hutchinson family were renamed after he left.

In Popular Culture

In the 2015 miniseries Sons of Liberty, Thomas Hutchinson is played by actor Sean Gilder.

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |