Anne Hutchinson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anne Hutchinson

|

|

|---|---|

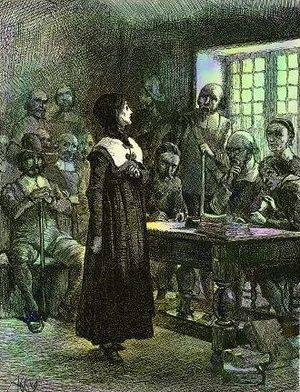

Anne Hutchinson on Trial

by Edwin Austin Abbey |

|

| Born |

Anne Marbury

Baptised 20 July 1591 |

| Died | August 1643 (aged 52) New Netherland (later The Bronx, New York, US)

|

| Education | Home schooled and self-taught |

| Occupation | Midwife |

| Known for | Role in the Antinomian Controversy |

| Spouse(s) | William Hutchinson |

| Children | Edward, Susanna, Richard, Faith, Bridget, Francis, Elizabeth, William, Samuel, Anne, Mary, Katherine, William, Susanna, Zuriel |

| Parent(s) | Francis Marbury and Bridget Dryden |

| Relatives | of Governor Peleg Sanford Great great grandmother of Governor Thomas Hutchinson< Ancestor of U.S. Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush |

Anne Hutchinson (born Anne Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was an important woman in early American history. She was a spiritual advisor and religious reformer. She played a big part in a major religious disagreement, called the Antinomian Controversy, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638.

Anne's strong religious beliefs were different from those of the main Puritan leaders in Boston. Her popularity and inspiring personality led to a religious split that worried the Puritan community in New England. Because of her views, she was eventually put on trial and asked to leave the colony. Many of her supporters left with her.

Hutchinson was born in Alford, England. Her father, Francis Marbury, was a church leader and teacher. He made sure Anne received a much better education than most girls at that time. As a young adult, she lived in London and married William Hutchinson, a friend from her hometown.

The couple moved back to Alford. There, they began following a preacher named John Cotton in nearby Boston, Lincolnshire. Cotton had to move to America in 1633. The Hutchinsons followed him a year later with their 11 children. They quickly settled in the growing town of Boston in New England.

Anne Hutchinson worked as a midwife, helping women during childbirth. She also openly shared her religious ideas. Soon, she began hosting weekly meetings at her home for women. They discussed recent sermons. These meetings became so popular that she started holding meetings for men too, including the young governor, Henry Vane.

Anne began to say that local ministers (except for John Cotton and her brother-in-law, John Wheelwright) were teaching that people could earn God's favor through good actions. She believed that God's favor was a gift, not something earned. Many ministers complained about her strong opinions and some of her different religious teachings. This disagreement grew into the Antinomian Controversy. It ended with her trial in 1637, where she was found guilty and told to leave the colony. In March 1638, her church also removed her from its membership.

Hutchinson and many of her followers started a new settlement called Portsmouth, Rhode Island. They were encouraged by Roger Williams, who founded Providence Plantations. This area later became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. After her husband died a few years later, Massachusetts threatened to take over Rhode Island. This made Anne move even further away, into lands controlled by the Dutch.

Five of her older children stayed in New England or England. Anne settled with her younger children near a famous rock called Split Rock. This area is now part of The Bronx in New York City. At that time, there was tension with the Siwanoy Native American tribe. In August 1643, Anne Hutchinson, six of her children, and other household members were killed by Siwanoys during Kieft's War. Her nine-year-old daughter, Susanna, was the only survivor. She was taken captive.

Anne Hutchinson is a key figure in the history of religious freedom in America. She also played a role in the history of women in religious leadership, by challenging the authority of male ministers. Massachusetts honors her with a monument at the Massachusetts State House. It calls her a "courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration." She is known as "the most famous—or infamous—English woman in colonial American history."

Contents

Anne's Early Life in England

Growing Up and Learning

Anne Marbury was born to Francis Marbury and Bridget Dryden in Alford, England. She was baptized on July 20, 1591. Her father was a church leader in London with strong Puritan beliefs. He believed that church leaders should be well educated. He often disagreed with his superiors about this.

Anne's father was even put in Marshalsea Prison for two years for his beliefs. He later used his experiences to teach his children. He showed them how to stand up for what they believed in.

In 1580, he was released and moved to Alford. He became an assistant priest and a schoolmaster. Anne's father believed strongly in learning. He made sure Anne received a better education than most girls of her time. She learned a lot about the Bible and Christian ideas. At that time, education was mostly for boys. But Anne's father taught his daughters, perhaps because six of his first seven children were girls. Also, leaders in Elizabethan England started to see that girls could be educated, like Queen Elizabeth I who spoke six languages.

In 1605, when Anne was 15, her family moved to London. Her father became a vicar there. He was able to express his Puritan views more openly. He died suddenly in February 1611, when Anne was 19.

Following John Cotton's Teachings

The year after her father's death, Anne Marbury, at age 21, married William Hutchinson. He was a fabric merchant from Alford. They married in London on August 9, 1612, and then moved back to Alford.

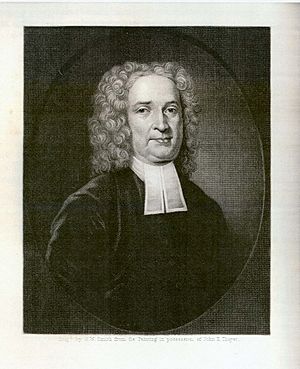

Soon, they heard about an inspiring minister named John Cotton. He preached at St Botolph's Church in Boston, Lincolnshire, about 21 miles from Alford. Cotton was known as one of England's leading Puritans. The Hutchinsons traveled to Boston as often as they could to hear him preach.

Cotton's message was different from other Puritans. He focused less on good behavior to gain God's salvation. Instead, he emphasized a moment of religious conversion where a person felt God's grace. Anne Hutchinson was drawn to Cotton's idea of "absolute grace." This made her question the importance of "works" (good deeds). She believed the Holy Spirit lived within chosen people. This idea gave women a sense of power, as their status was usually decided by their husbands or fathers.

Another important influence was Anne's brother-in-law, John Wheelwright. He was a young minister in nearby Bilsby and preached a similar message to Cotton's. Both Cotton and Wheelwright encouraged a feeling of religious rebirth among their church members. But their weekly sermons were not enough for some Puritan worshippers.

This led to "conventicles," which were small gatherings of people who felt they had found God's grace. They would discuss and pray about sermons. These meetings were very important for women. They allowed women to take on religious leadership roles that were usually denied to them in the male-dominated church. Anne Hutchinson was inspired by Cotton and other women who led these groups. She began holding her own meetings at home. She would review sermons and share her own explanations.

By 1633, Cotton's Puritan practices caught the attention of Archbishop William Laud. He was trying to stop any preaching that did not follow the rules of the Anglican Church. Cotton was removed from his ministry and went into hiding. To avoid prison, he quickly left for New England on a ship called the Griffin.

When Cotton left England, Anne Hutchinson felt very troubled. She felt she "could not be at rest" until she followed him to New England. Anne believed that the Spirit told her to go to America. She was pregnant with her 14th child, so she waited until after the baby was born. In 1634, 43-year-old Anne Hutchinson sailed from England with her husband William and their ten other children. They sailed on the Griffin, the same ship that had carried Cotton a year earlier.

Life in Boston

William Hutchinson was a successful merchant. He brought a lot of wealth with him to New England. They arrived in Boston in the late summer of 1634. The Hutchinson family bought land in what is now downtown Boston. They built a large house there, one of the biggest in the area. The Hutchinsons also gained land on Taylor's Island for their sheep. They also bought 600 acres of land south of Boston.

William Hutchinson continued to do well in his cloth business. He bought more land and made investments. He became a town leader and a representative in the General Court. Anne Hutchinson also settled into her new home easily. She spent many hours helping those who were sick or in need. She became an active midwife. While helping women give birth, she also gave them spiritual advice. A leader named John Winthrop noted that she often talked about "the things of the Kingdome of God." He also said her usual conversations were "in the way of righteousness and kindnesse."

Boston's Main Church

The Hutchinsons became members of the First Church in Boston. This was the most important church in the colony. Boston was New England's center for trade because of its harbor. Its church was where "Seamen and all Strangers came." The church grew quickly after John Cotton arrived.

Historian Michael Winship noted that the church seemed to be a perfect Christian community. Early Massachusetts historian William Hubbard said the church was "flourishing." It was unusual that the colony's most important church also had a minister, John Cotton, with somewhat different views. Because of Cotton's different ideas, the more extreme religious views of Anne Hutchinson and Governor Henry Vane did not stand out as much at first.

Home Bible Study Meetings

Anne Hutchinson's visits to women during childbirth led to discussions, much like the conventicles in England. She soon began hosting weekly meetings at her home. Women came to discuss Cotton's sermons and hear her explanations. Her meetings for women became so popular that she had to organize meetings for men too. She was hosting 60 or more people each week. These gatherings encouraged both women and their husbands to "enquire more seriously after the Lord Jesus Christ."

As the meetings continued, Anne Hutchinson began sharing her own religious views. She stressed that only a direct feeling from God would lead to one's salvation, not good actions. Her religious ideas started to differ from the stricter views of the colony's ministers. Attendance at her meetings grew, and even Governor Vane joined. Her ideas that outward behavior wasn't always linked to one's soul appealed to people like merchants and craftsmen.

The colony's ministers became more aware of Anne's meetings. They argued that such "unauthorized" religious gatherings might confuse people. Anne responded by quoting a Bible verse from Titus. It says that "the elder women should instruct the younger."

Moving to Rhode Island

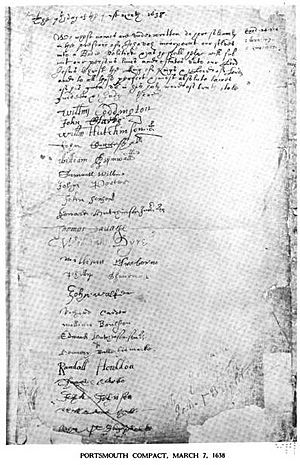

While Anne Hutchinson was held captive, some of her supporters prepared to leave Massachusetts. Her husband, William, was part of a group of men who met on March 7, 1638. They signed the Portsmouth Compact. This document formed them into a "Bodie Politick" (a political group). They elected William Coddington as their governor, calling him "judge."

Nineteen of the signers first planned to move to New Jersey or Long Island. But Roger Williams convinced them to settle near his Providence Plantations settlement. Coddington bought Aquidneck Island (later called Rhode Island) from the Narragansetts. They founded the settlement of Pocasset, which was soon renamed Portsmouth. Anne Hutchinson followed in April, after her church trial.

Anne, her children, and others traveled for more than six days in the April snow. They walked from Boston to Roger Williams' settlement at Providence. Then they took boats to Aquidneck Island. Many men had gone ahead to build houses. In the second week of April, Anne was reunited with her husband. They had been separated for almost six months.

Changes in Government

Less than a year after Pocasset was settled, it faced disagreements. Coddington had supported Anne Hutchinson. But he became too controlling and upset other settlers. In early 1639, Anne Hutchinson met Samuel Gorton. He questioned the power of the leaders. On April 28, 1639, Gorton and others removed Coddington from power. Anne may not have supported this, but her husband was chosen as the new governor.

Coddington and others left the colony. They started the settlement of Newport at the south end of the island. The people of Pocasset changed their town's name to Portsmouth. They created a new government that allowed trials by jury and separated church and state. The men who went with Coddington to Newport were strong leaders. Several later became governors of the united colony. On March 12, 1640, Portsmouth and Newport agreed to reunite. Coddington became governor of the island, and William Hutchinson was one of his assistants. The towns remained independent, with laws made by the citizens.

During her time in Portsmouth, Anne Hutchinson developed new religious ideas. She convinced her husband to resign from his position as a leader. Roger Williams said this was "because of the opinion, which she had newly taken up, of the unlawfulness of magistracy" (meaning she believed it was wrong for religious leaders to hold government power).

Anne's husband, William, died sometime after June 1641 at age 55. He was buried in Portsmouth. There is no official record of his death. This is because there was no established church, which would have kept such records.

Moving to New Netherland

Soon after settling Aquidneck Island, the Massachusetts Bay Colony threatened to take over the island. This worried Anne Hutchinson and other settlers. It made her decide to move completely out of reach of Massachusetts. She moved into the area controlled by the Dutch, called New Netherland.

Anne Hutchinson went to New Netherland sometime after the summer of 1642. She traveled with seven of her children, a son-in-law, and several servants—16 people in total. They settled near an old landmark called Split Rock. This was not far from what became the Hutchinson River in northern Bronx, New York City. Other families from Rhode Island were also in the area.

The Hutchinsons stayed temporarily in an empty house. A permanent house was being built with help from James Sands. The local Native Americans showed signs that they were not happy with the new settlement. The land had supposedly been bought by a Dutch company in 1640. But the deal was made with members of the Siwanoy people far away in Norwalk. The local Siwanoy likely knew little about it. So, Anne Hutchinson took a big risk by building a permanent home there.

The exact spot of the Hutchinson house has been a mystery for centuries. Some believe it was near an old Indian Trail in modern-day Pelham Bay Park. Others think it was on the west side of the Hutchinson River in Eastchester. This area of the Bronx is now very developed.

Anne Hutchinson's Death

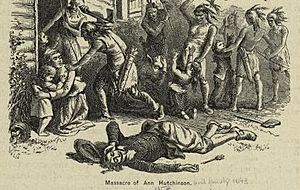

The Hutchinsons settled in this area during a time of conflict between the colonists and the Native Americans. The Dutch leader, Willem Kieft, had angered the Native Americans. He ordered attacks on their settlements to drive them away. Mrs. Hutchinson had a good relationship with the Narragansetts in Rhode Island. She may have felt safe among the Siwanoy of New Netherland. The Hutchinsons had been friendly to them. However, the Native Americans attacked the New Netherland colony in a series of events known as Kieft's War.

According to one historian, Siwanoy warriors stormed into the small settlement above Pelham Bay. They planned to burn every house. The Siwanoy chief, Wampage, had sent a warning. He expected to find no settlers there. However, the Hutchinsons were at home at that moment and were killed.

The warriors then burned the house. During the attack, Anne Hutchinson's nine-year-old daughter, Susanna, was picking blueberries. Legend says she was found hiding in a crack of Split Rock nearby. She is believed to have had red hair, which was unusual to the Native Americans. Perhaps because of this, her life was spared. She was taken captive and lived with the Native Americans for two to six years. She was later returned to her family members, most of whom lived in Boston.

The exact date of the Hutchinson massacre is not known. The first clear record of it was in John Winthrop's journal. It was the first entry for September, but not dated. It took days or weeks for Winthrop to get the news. So, the event almost certainly happened in August 1643. This is the date found in most historical sources.

The reaction in Massachusetts to Anne Hutchinson's death was harsh. Some religious leaders saw it as God's judgment against her.

Anne Hutchinson's Impact on History

Anne Hutchinson said she was a prophet, receiving direct messages from God. During her trial, she predicted that God would judge the Massachusetts Bay Colony. She also taught her followers that personal messages from God were as important as the Bible. This idea was completely against Puritan beliefs. She also claimed she could identify "the elect" (those chosen by God) among the colonists. These beliefs led John Cotton, John Winthrop, and others to see her as a heretic.

Historian Michael Winship says that Anne Hutchinson is famous not just for what she did. She is also famous for how John Winthrop wrote about her in his journal. Winthrop unfairly blamed Anne Hutchinson for all the problems the colony faced. With her departure, other issues were ignored. Winthrop's writings gave Hutchinson a legendary status. Over time, what she stood for has changed. Winthrop described her as "a woman of ready wit and bold spirit." To Winthrop, Hutchinson was a "hell-spawned agent of destructive anarchy."

In Massachusetts Bay, the church and government were closely linked. So, challenging the ministers was seen as challenging all authority. In the 1800s, Americans saw her as a champion for religious freedom. This was as the nation celebrated the separation of church and state. In the 1900s, she became a feminist leader. She was seen as someone who challenged male leaders, not just for her religious views, but because she was a strong woman.

Historian Amy Lang argues that it was hard for the court to find a crime she committed. Lang believes her real "crime" was breaking her role in Puritan society. She was condemned for acting as a teacher, minister, leader, and husband. However, the Puritans themselves said the threat they felt was purely religious. They never directly mentioned being threatened by her gender.

Winship calls Hutchinson "a prophet, spiritual adviser, mother of fifteen, and important participant in a fierce religious controversy." She is seen as a symbol of religious freedom, liberal thinking, and Christian feminism. Anne Hutchinson is a debated figure. She has been praised, made into a myth, and criticized by different writers. Historians have looked at her life through different lenses. These include the role of women, power struggles in the Church, and conflicts within the government. Winship writes, "Hutchinson's well-publicized trials and the attendant accusations against her made her the most famous, or infamous, English woman in colonial American history."

Memorials and Legacy

In front of the Massachusetts State House in Boston, there is a Statue of Anne Hutchinson with her daughter Susanna. The statue was dedicated in 1922. The inscription on the marble base reads:

IN MEMORY OF

ANNE MARBURY HUTCHINSON

BAPTIZED AT ALFORD

LINCOLNSHIRE ENGLAND

20 JULY 1595 [sic]

KILLED BY THE INDIANS

AT EAST CHESTER NEW YORK 1643

COURAGEOUS EXPONENT

OF CIVIL LIBERTY

AND RELIGIOUS TOLERATION

This memorial is part of the Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

Another memorial to Anne Hutchinson is south of Boston in Quincy, Massachusetts. It is at the corner of Beale Street and Grandview Avenue. This is near where the Hutchinsons owned a 600-acre farm. They stayed there for several days in early spring 1638 while traveling from Boston to their new home on Aquidneck Island.

There is also an Anne Hutchinson memorial in Founders' Brook Park in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. The park has marble stones with quotes from Hutchinson's trial.

Anne Hutchinson was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1994.

Literary Works

Some literary experts believe the character of Hester Prynne in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter was inspired by Anne Hutchinson's struggles. Historian Amy Lang wrote that Hester Prynne was like a fictional Anne Hutchinson. She was the kind of person early Puritan writers said Hutchinson was.

Hawthorne said The Scarlet Letter was inspired by John Neal's 1828 novel Rachel Dyer. In that book, Hutchinson's fictional granddaughter is a victim of the Salem witch trials. Anne Hutchinson appears in the first chapters as a martyr.

Anne Hutchinson and her struggles with Governor Winthrop are shown in the 1980 play Goodly Creatures by William Gibson. Other historical figures in the play include Reverend John Cotton and Governor Harry Vane. In January 2014, an opera called Anne Hutchinson was performed in Boston.

Places Named After Her

In southern New York, the Hutchinson River and the Hutchinson River Parkway are named after Anne Hutchinson. The river is one of the few named after a woman. Elementary schools in Westchester County towns like Pelham and Eastchester are also named for her.

In Portsmouth, Rhode Island, Anne Hutchinson and her friend Mary Dyer are remembered at Founders Brook Park. There is an Anne Hutchinson/Mary Dyer Memorial Herb Garden there. It is a garden of medicinal plants next to a waterfall and a historical marker. The garden was created by artist Michael Steven Ford, who is a descendant of both women. A local group called Friends of Anne Hutchinson meets yearly at the memorial. They celebrate her life and the history of women on Aquidneck Island. Hutchinson Hall, a dorm at the University of Rhode Island, is also named in her honor.

Official Pardon

In 1987, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis officially pardoned Anne Hutchinson. He canceled the banishment order made by Governor Winthrop 350 years earlier.

Anne Hutchinson's Family

Immediate Family

Anne and William Hutchinson had 15 children. All but the last child were born and baptized in Alford, England. The last child was baptized in Boston, Massachusetts. Of the 14 children born in England, 11 lived to sail to New England.

The oldest child, Edward, was baptized on May 28, 1613. He signed the Portsmouth Compact and settled on Aquidneck Island with his parents. But he later made peace with Massachusetts and returned to Boston. He was an officer in the colonial army. He died from wounds during King Philip's War.

Susanna was baptized on September 4, 1614, and died in Alford during the plague in 1630. Richard (baptized December 8, 1615) joined the Boston church in 1634. But he returned to England, and no more is known about him. Faith (baptized August 14, 1617) married Thomas Savage and lived in Boston. She died around 1651. Bridget (baptized January 15, 1618/9) married John Sanford. She lived in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, where her husband was briefly governor. After his death, she married William Phillips and had three sons. She died by 1698.

Francis (baptized December 24, 1620) was the oldest child to die in the massacre in New Netherland. Elizabeth (baptized February 17, 1621/2) died during the plague in Alford. William (baptized June 22, 1623) died as a baby. Samuel (baptized December 17, 1624) lived in Boston, married, and had a child. But few records remain about him. Anne (baptized May 5, 1626) married William Collins. Both went to New Netherland and died in the massacre with her mother.

Mary (baptized February 22, 1627/8), Katherine (baptized February 7, 1629/30), William (baptized September 28, 1631), and Zuriel (baptized in Boston March 13, 1635/6) were all children when they went with their mother to New Netherland. They were killed during the Native American attack in late summer 1643. Susanna was the 14th child and the youngest born in England, baptized November 15, 1633. She survived the attack in 1643. She was taken captive and later traded back to the English. She then married John Cole and had 11 children.

Of Anne Hutchinson's many siblings who lived past childhood, only one other came to New England. Her youngest sister, Katherine, came to Boston and then Providence. With her husband, Katherine was a Puritan, then a Baptist, and later a Quaker.

Famous Descendants

Many of Anne Hutchinson's descendants became very famous. These include United States Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush. Also, presidential candidates Stephen A. Douglas, George W. Romney, and Mitt Romney are her descendants. Her grandson Peleg Sanford was a governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

Other descendants include Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court Melville Weston Fuller and Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.. The first Lord Chancellor of England, John Singleton Copley, Jr., was also a descendant. President of Harvard University Charles William Eliot, actor Ted Danson, and musician Kaitlyn ni Donovan are also descendants. One descendant with the Hutchinson name was her great-great-grandson Thomas Hutchinson. He was a governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay during the Boston Tea Party. This event led to the American Revolutionary War.

See also

In Spanish: Anne Hutchinson para niños

In Spanish: Anne Hutchinson para niños

- Christian egalitarianism

- Christian views about women

- List of colonial governors of Rhode Island

- Mary Dyer

Images for kids

-

Split Rock, near where the Hutchinson family was massacred

-

Major Thomas Savage married Hutchinson's daughter Faith

-

Stephen A. Douglas was descended from Hutchinson

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |