John Neal (writer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Neal

Esq.

|

|

|---|---|

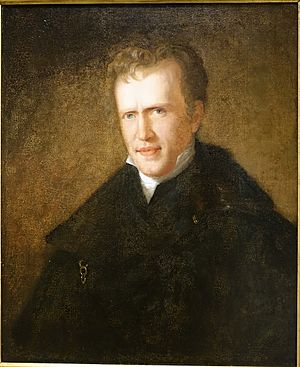

Portrait by Sarah Miriam Peale circa 1823

|

|

| Born | August 25, 1793 Portland, District of Maine, United States |

| Died | June 20, 1876 (aged 82) Portland, Maine, United States |

| Resting place | Western Cemetery Portland, Maine, United States |

| Pen name |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

John Neal (August 25, 1793 – June 20, 1876) was an American writer, critic, editor, and activist. He was known for being a bit unusual but also very influential. From the 1810s to the 1870s, he gave speeches and wrote many essays, novels, poems, and short stories. He was a big supporter of American literature and helped start the idea of writing about different regions of the US.

Neal also helped American art grow and fought for women's rights. He wanted to end slavery and prejudice against different races. He even helped start the gymnastics movement in America. He was the first American author to use natural, everyday language in his writing. He was also the first American writer to be published in British literary magazines.

John Neal was one of the first men in the US to speak up for women's rights. For over 50 years, he supported female writers and activists. He believed men and women were equally smart. He fought against laws that stopped women from owning property or earning money. He also demanded voting rights, equal pay, and better education for women. He opened the first public gym in the US. He believed sports could help people control their anger, something he struggled with himself.

Neal mostly taught himself, leaving school at age 12. He worked from a young age. By the time he was in his middle years, he was quite wealthy and respected in his hometown of Portland, Maine. This was thanks to his smart investments and his work in arts and community leadership.

Many people say Neal didn't write one single "masterpiece." But his short stories are considered his best work. His novel Rachel Dyer is often called his top novel. His speech "Rights of Women" (1843) was very important for the women's rights movement.

Contents

John Neal's Early Life and Work

Childhood and First Jobs

John Neal and his twin sister Rachel were born in Portland, Maine on August 25, 1793. Their father, also named John Neal, was a teacher. He died just a month after they were born. Their mother, Rachel Hall Neal, was a smart and independent woman. She started her own school and rented rooms to boarders to earn money. Their Quaker community also helped the family. Neal grew up in "genteel poverty," meaning they were poor but tried to keep up appearances. He went to his mother's school, a Quaker boarding school, and a public school.

Neal said his lifelong struggle with a bad temper started at public school. He was bullied and physically hurt by classmates and the teacher. To help his mother, Neal left school and home at age 12 to work full-time.

As a teenager, he sold clothes and other goods in Portland and Portsmouth. He learned some dishonest business tricks, like using fake money. He lost jobs many times because businesses failed due to US trade rules against British goods. Neal then traveled through Maine, teaching penmanship, watercolor painting, and how to draw tiny portraits. In 1814, at age 20, he moved to Boston for a job at a dry goods shop.

In Boston, Neal partnered with John Pierpont and Pierpont's brother-in-law. They made quick money by smuggling British goods during the War of 1812. They opened stores in Boston, Baltimore, and Charleston. But after the war, a recession hit, and Neal and Pierpont went bankrupt in Baltimore in 1816. Even though their business failed, Neal and Pierpont became very close friends for life.

Neal's business failures made him proud and ambitious. He believed he had to rely on his own skills to succeed in the future.

Building a Career in Baltimore

From 1816 to 1823, Neal was incredibly busy in Baltimore. He worked as an editor, journalist, poet, novelist, and studied law. He taught himself to read and write in many languages. He published seven books and studied law in just 18 months, a course that usually took seven or eight years. He became a lawyer in 1820. He also wrote a lot for newspapers and magazines, editing two of them.

After his bankruptcy, Neal started writing for The Portico magazine. He became one of its most frequent writers, though he was never paid. He later became the editor for its last issue. He also helped start the Delphian Club in 1816, a group of smart and friendly people who helped him a lot. While writing his early poems, novels, and essays, he studied law for free in a lawyer's office.

Neal's business failure left him with no money. He decided to try writing novels. At that time, very few American novels had been published. He was inspired by his friend Pierpont's success with a poem. Neal felt that writing was his only choice if he wanted to study law.

In 1819, he published a play and got his first paid job as a newspaper editor. He also wrote most of History of the American Revolution. His many writings earned him the nickname "Jehu O'Cataract." This work helped him pay his bills while he finished his law studies. He became a practicing lawyer in Baltimore in 1820.

Neal's last years in Baltimore were his most active as a novelist. He published one novel in 1822 and three more in 1823. He became a main competitor to James Fenimore Cooper as America's top novelist. During this time, he left the Delphian Club on bad terms. He was also kicked out of the Quaker community after being in a street fight. He had a public argument with a lawyer's son after publishing insults about the lawyer. Neal hated being a lawyer, feeling like he was "in open war" with all lawyers. He was also making enemies with friends and critics.

By late 1823, Neal wanted to leave Baltimore. He said a friend quoted a British writer who asked, "who reads an American book?" This made Neal want to go to London. He left for the UK on December 15, 1823.

Writing in London

Neal went to London with three main goals. He wanted to become the most important American writer, create a new American writing style, and change how British writers viewed American authors. He hoped to get paid by London publishers who had already copied his books. But they refused to pay him.

Neal only brought enough money to last a few months. He thought he could live on very little and write faster than anyone. His money was almost gone when William Blackwood asked him to write for Blackwood's Magazine in April 1824. For the next year and a half, Neal was paid well and wrote a lot for the magazine.

His first article in Blackwood's was about the US presidential candidates of 1824. It was the first article by an American in a British literary magazine and was widely shared. His "American Writers" series, the first history of American literature, was his most important work for the magazine. Blackwood's also published his early writings on women's rights and his novel Brother Jonathan. But an argument over changes to his writing ended their relationship in late 1825. Neal was again without income.

After writing for other British magazines for less money, John Neal, then 32, met 77-year-old philosopher Jeremy Bentham. In late 1825, Bentham offered Neal a place to live and a job as his personal secretary. Neal spent the next year and a half writing for Bentham's Westminster Review.

In spring 1827, Bentham paid for Neal to return to the US. Neal had gotten the attention of British writers and published a novel. He felt he had succeeded in teaching the British about American life. However, Brother Jonathan was not seen as the great American novel he hoped for. He returned to the US no longer seen as Cooper's main rival.

John Neal's Return to Portland

Championing Athletics and New Ideas

Neal returned to the US in June 1827. He planned to live in New York City but stopped in Portland to see his family. There, people were angry at him. He had made fun of important citizens in his book Errata. He had also made fun of New England accents and habits in Brother Jonathan. And he had criticized American writers in Blackwood's Magazine. People put up posters, argued with him in the streets, and tried to stop him from practicing law. Neal decided to stay in Portland to show them he wouldn't be scared away.

Neal had learned about new sports like German gymnastics, boxing, and fencing while abroad. He became a big supporter of these sports in the US. In 1827, he opened Maine's first gym, making him the first American to open a public gym in the US. He taught boxing and fencing in his law office. That same year, he opened gyms in nearby Saco and at Bowdoin College. He had also written articles about German gymnastics and urged Thomas Jefferson to include a gym at the University of Virginia. Neal believed sports helped him control his violent temper.

In 1828, Neal started The Yankee magazine and was its editor until the end of 1829. He used the magazine to defend himself to people in Portland. He also wrote about American art and theater, discussed what it meant to be from New England, shared his growing ideas about feminism, and encouraged new writers, many of whom were women. Neal edited many other magazines and newspapers between the late 1820s and mid-1840s. He was a popular writer on many topics.

Neal published three novels using material he wrote in London. He also focused on writing short stories, which are considered his best literary work. He published about one story a year between 1828 and 1846, helping to shape this new type of writing. He started giving lectures in 1829. He became very influential in the women's rights movement around 1843, giving speeches to large crowds and reaching more people through newspapers. His busy life was described by his law apprentice, James Brooks, in 1833:

border-left: 3px solid #ccc;

Neal was a boxing and fencing master. When a printer's assistant came crying for more writing, he would race with a huge quill pen, writing very fast. Then he would give a boxing lesson, with the sound of gloves hitting, then a fencing lesson, with the sound of masks and foils.

Family Life and Community Work

In 1828, Neal married his second cousin, Eleanor Hall. They had five children between 1829 and 1847. They raised their children in the house he built in Portland in 1836. That same year, he received an honorary master's degree from Bowdoin College. This was the same college where he had taught penmanship as a teenager.

After the 1830s, Neal spent less time on writing and more on business, activism, and local arts and community projects. This was especially true after he inherited money from two uncles. He no longer needed to rely on writing for income. In 1845, he became the first agent for a life insurance company in Maine. He earned enough money to stop lecturing, practicing law, and most writing. Neal started buying and selling local real estate. He also ran granite quarries, helped build railroad connections to Portland, and invested in land in Cairo, Illinois. He led the effort to make Portland a city and build its first parks and sidewalks. He also became interested in architecture and furniture design, creating simple and useful designs that influenced others.

Many writers at the time thought Neal had disappeared. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote in 1845 that "that wild fellow, John Neal," must be "dead, else he never could keep himself so quiet." Henry Wadsworth Longfellow described Neal in 1860 as "a good deal tempered down but fire enough still."

After years of loosely following Unitarianism and universalism, Neal joined the Congregational church in 1851. His deeper religious faith gave him new reasons to fight for women's rights. It also helped him control his violent tendencies and inspired him to write seven religious essays.

At the urging of friends like Longfellow, John Neal returned to writing novels later in life. He published True Womanhood in 1859. From 1863 to 1866, he wrote three dime novels to earn money. In 1869, he published his autobiography, Wandering Recollections of a Somewhat Busy Life, which is considered very entertaining. Thinking about his life made Neal want to do more activism. He took on leadership roles in the women's voting rights movement. His last two books were Great Mysteries and Little Plagues (1870), a collection for children, and Portland Illustrated (1874), a guide to his hometown.

By 1870, in his old age, he had saved a lot of money. His last public appearance was likely in 1875. An article said that 81-year-old Neal physically stopped a young man from smoking on a non-smoking streetcar. John Neal died on June 20, 1876, and was buried in Portland's Western Cemetery.

John Neal's Writing Style

Neal's writing career lasted almost 60 years. His most important literary works were published between 1817 and 1835. His writing showed and challenged the changing ways of life in America during those years. He started writing when Americans were just beginning to read more books. He wrote a lot for newspapers and magazines throughout his life, especially in the 1830s. He wrote essays on many topics, including art, literature, phrenology, women's rights, gymnastics, and slavery.

Neal worked to make American literature unique and less like British writing. Many people now give him credit for this, though earlier scholars gave credit to others. His short stories are considered his best writing. They are ranked with the works of famous authors like Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe. John Neal is often seen as an important American writer, even if he doesn't have one famous "masterpiece."

His Unique Style

Unlike other American writers of his time, Neal's early novels showed dark, troubled heroes. He didn't like to edit his work much. He wrote very quickly to define his style and make his books sell well. He wanted to create a new American literature. Neal was a pioneer of "natural writing," meaning he was the first in America to use everyday language. His work was different from the polite writing style of others. Neal said he would "never write what is now worshipped under the name of classical English," calling it "the deadest language."

After the War of 1812, many writers wanted a unique American literature. But Neal felt their work was too much like British writing. He believed that to succeed, he had to be different from everyone else. He wanted to declare "another Declaration of Independence" in the world of books. To do this, he used American characters, settings, historical events, and ways of speaking. He criticized British writers, saying they wrote for fun, while American authors wrote to make a living. By using the common language of Americans in his stories, Neal hoped to reach more readers. This would help ensure that American literature could survive financially.

In the late 1820s, Neal started focusing on regionalism instead of just nationalism. He wanted to show the different cultures and ways of life within the United States. His magazine The Yankee helped readers see the nation as a collection of different voices. He was one of the first writers to use everyday speech and regional accents in his writing. He wanted to preserve these differences in American English.

Short Stories

Neal's short stories are considered his best literary achievement. He published about one story a year between 1828 and 1846. He helped shape the new genre of short stories, especially early children's literature.

His best short stories are "Otter-Bag, the Oneida Chief" (1829) and "David Whicher" (1832). These stories are seen as better than the works of his more famous friends. They added something new to storytelling that wasn't seen much in American fiction until later authors like Herman Melville and Mark Twain. "David Whicher" was published without his name and wasn't known to be his until the 1960s. "The Haunted Man" (1832) is important because it was the first story to use ideas from psychotherapy. "The Old Pussy-Cat and the Two Little Pussy-Cats" and "The Life and Adventures of Tom Pop" (1835) are considered early works of children's literature.

Neal's stories, like his essays and lectures, challenged social and political issues of his time. These included manifest destiny, the idea of expanding the country, removing Native Americans, and the role of women. "David Whicher" challenged the popular idea that frontiersmen and Native Americans were always enemies. His stories also used humor to talk about social and political issues.

Novels

Most of John Neal's novels were published between 1817 and 1833. He wrote and published his first five novels in Baltimore: Keep Cool (1817), Logan (1822), Seventy-Six (1823), Randolph (1823), and Errata (1823). He wrote Brother Jonathan in Baltimore but published it in London in 1825. He published Rachel Dyer (1828), Authorship (1830), and The Down-Easters (1833) while living in Portland, Maine. These were all based on earlier writings from London.

Keep Cool, Neal's first novel, made him "the first in America to be natural in his diction." It also made him the "father of American subversive fiction."

Seventy-Six was Neal's favorite novel. When it came out in 1823, Neal was a very popular novelist, a main rival to James Fenimore Cooper. Neal was inspired by Cooper's The Spy. He based his story on historical research he did while helping his friend Paul Allen write History of the American Revolution.

Poetry

Most of Neal's poetry was published in The Portico while he was studying law in Baltimore. His only collection of poems was Battle of Niagara, A Poem, without Notes; and Goldau, or the Maniac Harper, published in 1818. Even though Battle of Niagara didn't make him famous or rich, it's considered the best poem about Niagara Falls up to that time. Neal's poems also appeared in other collections.

John Neal as an Editor

| Title | Period | Headquarters |

|---|---|---|

| The Portico | Final issue: April–June 1818 | Baltimore, MD |

| Federal Republican and Baltimore Telegraph | February–July 1819 | Baltimore, MD |

| The Yankee | January 1, 1828 – December 1829 | Portland, ME |

| The New-England Galaxy | January–December 1835 | Boston, MA |

| The New World | January–April 1840 | New York, NY |

| Brother Jonathan | May–December 1843 | New York, NY |

| Portland Transcript | June 10 – July 8, 1848 | Portland, ME |

Neal got his first two editing jobs through friends in the Delphian Club in Baltimore. His longest time as an editor was for The Yankee, which he started a few months after returning from London in 1827. It was Maine's first literary magazine. It was published weekly until it merged with a Boston magazine for financial reasons. When he started his last editing job, he joked that he had "ten or fifteen minutes to spare." A few weeks later, the next editor announced that Neal had left because his "fifteen minutes had expired."

Even though Neal said he supported Bentham's ideas in The Yankee, he spent more space promoting Northern New England and American regionalism. His regionalism was different from later writers who looked back at regions with nostalgia. Instead, Neal saw regions as active, forward-looking places.

The Yankee was controversial because it wasn't tied to any political party. This allowed it to cover many different topics. The magazine's biggest impact was helping new writers like John Greenleaf Whittier, Edgar Allan Poe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Most of the new writers he published and wrote about in The Yankee were women.

John Neal as a Lecturer

Between 1829 and 1848, Neal earned extra money by giving lectures. He traveled on the lyceum circuit, speaking on topics like literature, art, political economy, temperance, public speaking, and law.

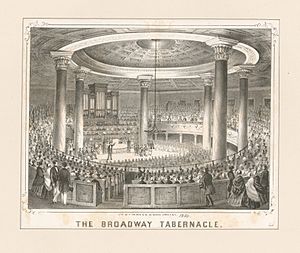

In 1832, he was asked to speak about freedom in Portland, Maine, on Independence Day. Neal gave an unprepared speech that was his first on women's rights. He used the ideas of the American Revolution to attack slavery as a denial of liberty. He also criticized the fact that women couldn't vote or control their own money, calling it "taxation without representation." Women's rights became a favorite topic for his lectures between 1832 and 1843. He gave speeches throughout the northeastern states. His speeches were often published in newspapers, which spread his ideas to even more people. Margaret Fuller admired Neal's "magnetic genius" and "lion heart" as a lecturer. His most popular speech was the 1843 "Rights of Women" speech at the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City.

John Neal's Activism

Throughout his adult life, Neal used articles, stories, novels, lectures, and his personal connections to address many issues. These included feminism, women's rights, slavery, rights of free Black Americans, rights of American Indians, dueling, temperance, lotteries, capital punishment, and social classes. Of these, "women's rights were the cause for which he fought longer and more consistently than for any other." Much of his work showed that he didn't trust big institutions. He always asked people to think for themselves and rely on their own strength.

Neal was also involved in William Henry Harrison's 1840 presidential campaign. He also supported pseudoscience movements like phrenology (studying bumps on the head to learn about personality) and animal magnetism.

Fighting for Women's Rights

Neal was America's first lecturer on women's rights. He was also one of the first men to support women's rights and feminist causes in the US. From as early as 1817 to as late as 1873, he used his writing, lectures, and political work to advance women's issues in the US and UK. He was most influential in this area around 1843. Neal supported female writers and activists. He believed men and women were equally smart. He fought against laws that prevented women from controlling their own money. He demanded voting rights, equal pay, and better education for women.

After the Civil War, Neal became very involved in the women's voting rights movement. He was influential in local, regional, and national groups. When the American Equal Rights Association split in 1869 over the Fifteenth Amendment (which gave voting rights to Black men), Neal supported the National Woman Suffrage Association. This group insisted on immediate voting rights for all women. He helped start the New England Woman Suffrage Association in 1868. He organized Portland's first public meeting on women's voting rights in 1870. And he helped start Maine's first statewide Woman Suffrage Association in 1873.

Fighting Against Slavery

Neal was strongly against slavery. He believed that the ideals of the Declaration of Independence meant that enslaved people in America were born free. He thought they had the right to change a government that kept them enslaved.

He believed that ending slavery all at once was impossible. He thought it would make Black Americans a "dreaded caste" in the US. So, he supported "gradual emancipation," which had worked well in New England and New York. He called for the government to pay slave owners to free enslaved people. This would spread the cost across all states.

Neal supported the American Colonization Society. He founded the Portland, Maine, chapter in 1833 and served as its secretary. He later met with Liberia's first president, Joseph Jenkins Roberts. Neal likely avoided the movement for "immediate, unconditional, and universal emancipation" because of a long-standing disagreement with William Lloyd Garrison. This disagreement wasn't resolved until Neal admitted in 1865 that he "was wrong... and Mr. Garrison was right."

Rights for Black Americans

Neal spoke out against denying voting rights to free Black Americans. He showed how "free-born Americans... because of their colour," were not allowed to vote. This happened not just in the slave states but also in states where slavery was hated. He was worried about "practical racism" among white Northerners. He pointed out that members of his gym in 1828 voted that "no colored man... can be permitted to exercise with white citizens of our free and equal-community." Neal was disappointed they wouldn't let Black men join, so he stopped being involved with the gym soon after. In his stories, Neal explored the differences in prejudice against Black Americans in the North and South.

Rights for Native Americans

Neal wrote essays, novels, and short stories to support the rights of American Indians. At a time when "native American" often meant white Anglo-Americans, Neal declared in his first novel (1817) that "the Indian is the only native American." In an 1824 essay, Neal said that American Indians "have never been the aggressors" in conflicts with European-Americans. He said they had been "deplorably oppressed, belied, and wronged." He called for recognizing Indigenous sovereignty. He criticized how the "law of nations" was ignored when dealing with them. He said their leaders were imprisoned and killed, and war was never officially declared against them.

Neal described how the US government took Indigenous land:

border-left: 3px solid #ccc;

The people on the frontier start a fight with the Indians... No war is declared; no ceremony; but, General [Andrew] Jackson—or someone else; goes out, destroying and burning the whole country. A truce follows: the conquered land is given up—for the protection of the white people.

Neal used novels like Logan (1822) to challenge racial barriers between white and Indigenous Americans. After the Indian Removal Act (1830), Neal published the short story "David Whicher" (1832). This story explored how different ethnic groups could live together peacefully in the US.

Opposing Dueling

In his first novel (1817), Neal said dueling was an old, aristocratic practice that was wrong, pointless, and against American democracy. He said that in America, "a gentleman may cut another's throat, or blow out his brains with complete impunity." His "Essay on Duelling" that same year attacked dueling as a way for men to prove their "manhood." He believed that everyone secretly wanted dueling to end. If they spoke out publicly, it would be abolished.

Social Hierarchy

Neal's Quaker upbringing likely made him dislike "worldly titles." He felt they didn't fit in a republican society. He made fun of them in his writing. In an 1824 essay, he said the US had moved away from its ideals of equality. He noted that "titles are multiplying" and even pride in family history had grown. As a lawyer, he refused to call Chief Justice John Marshall or any other judge "your honor." He believed that "there is no greater humbug in the minds of men than this obsequious bowing to men of high station." He felt the real thinkers and workers were the important people.

Militia Tax

In his 1826 essay "United States," Neal first argued against the poll tax that paid for the US militia system. He showed that both "the poor and the rich are taxed... under the militia law." This law was meant to protect the property of the rich. But the rich didn't fight, the poor did. The poor couldn't afford to stay home, but the rich could. He suggested replacing the poll tax with a property tax to pay men serving in militias. This would make the system fairer.

Lotteries

Neal started arguing against lotteries in Baltimore newspapers when he was a law apprentice. He continued in his novel Logan (1822). He argued that the law should treat lotteries like other forms of gambling. His ideas influenced people across the US and in the UK. In The Yankee, he fought against all lottery offices until the system was "up-rooted... throughout our whole country." Lotteries became unpopular in the US in the 1830s.

Capital Punishment

Neal began his fight against public executions after seeing one in Baltimore. He attacked capital punishment in newspapers, magazines, novels, and debates. He became influential in the US and reached some people in the UK.

Bankruptcy Law

Neal became active in changing bankruptcy laws soon after his own bankruptcy in 1816. As a young lawyer in Baltimore, he disagreed with Chief Justice Marshall's opinion in Sturges v. Crowninshield (1819). He played an important role in the movement for a national bankruptcy law. He also attacked the policy of imprisonment for debt in his Baltimore novels and in American and British newspapers in the 1820s.

John Neal's Legacy

A Talented but Scattered Writer

I AM called upon for a Preface. Like the "weary knife-grinder," when asked for a story, I am half tempted to answer, "Preface! God bless you! I've none to give you, sir!"

My book itself is only a Preface. And what, after all, is any Life but a preface?—a preface to something better—or worse?

On the whole, therefore, I think it safer for me, and better for the reader, whom I hope to be on good terms with, before he gets through, whatever may be his present notions upon the subject, not to trouble him with a Preface.

Many people thought Neal was a very smart but disorganized writer. One biographer said he "scattered his genius into many channels." Historian Edward H. Elwell said he "wrote for everything because he could not write long for anything." Neal himself admitted that being a newspaper editor for a year was "a long while, for any thing I had to do with." Edgar Allan Poe said John Neal was one of America's top "geniuses." But Poe also said his work was "massive and undetailed" and "hurried."

Writers and scholars often wished Neal had achieved more. In an 1848 poem, James Russell Lowell said Neal was "a man who made less than he might have." He said Neal was good at creating many ideas but never finished a "star" work. Lowell concluded that if Neal "could only have waited he might have been great."

His Influence on Other Writers

Neal's creative work indirectly influenced many writers during and after his life. Seba Smith, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow all enjoyed and were influenced by Neal's early poems and novels. Seba Smith's famous "Jack Downing" humor series was likely influenced by Neal's funny use of regional accents. It's also likely that Edgar Allan Poe developed many of his writing traits from Neal's articles in The Yankee in the late 1820s.

Many scholars believe that the most important authors of the mid-1800s American Renaissance learned techniques from Neal's earlier work. These include Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, and Herman Melville. One biographer pointed out that Neal clearly connected to these later masters, while earlier writers like Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper did not. He also argued that Neal's ability to influence very different writers like Poe and Whitman shows how important his work was.

His Place in History

Earlier scholars in the 1900s saw John Neal as a "transitional figure" in literature. They placed him after the first wave of American writers who copied British styles, but before the great American Renaissance. More recent studies say Neal was not "beneath" the American Renaissance, but "scattered across it." Scholars argue that Neal was left out of the Renaissance because he lived far from the Boston-Concord literary group. Also, he used popular writing styles that were seen as less artistic.

Selected Works by John Neal

|

Novels

Posthumous collections

|

Short stories

Poems

Drama

Other works

|

See also

In Spanish: John Neal (escritor) para niños

In Spanish: John Neal (escritor) para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |