Margaret Fuller facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Margaret Fuller

|

|

|---|---|

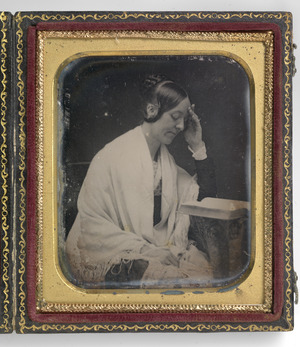

The only known daguerreotype of Margaret Fuller (by John Plumbe, 1846)

|

|

| Born | Sarah Margaret Fuller May 23, 1810 Cambridgeport, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | July 19, 1850 (aged 40) Off Fire Island, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Teacher Journalist Critic |

| Literary movement | Transcendentalism |

| Signature | |

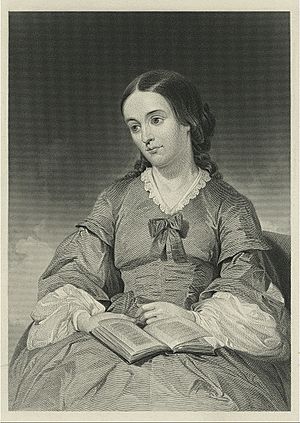

Sarah Margaret Fuller Ossoli (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850) was an American journalist, editor, and critic. She was also a strong supporter of women's rights and was part of the American transcendentalism movement. Margaret Fuller was the first American woman to work as a war correspondent and a full-time book reviewer in journalism. Her important book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, is seen as the first major feminist work in the United States.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Margaret Fuller received a very good early education from her father. She later became a teacher. In 1839, she started her "Conversations" series. These were classes for women, designed to make up for the fact that women couldn't easily go to college. In 1840, she became the first editor of the transcendentalist magazine The Dial. This was when her writing career really took off. In 1844, she joined the New-York Tribune newspaper, working for Horace Greeley. By her 30s, she was known as one of the most well-read people in New England. She was also the first woman allowed to use the library at Harvard College. Her famous book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, came out in 1845. A year later, the Tribune sent her to Europe as their first female reporter. She became involved with the revolutions in Italy and supported Giuseppe Mazzini. She married Giovanni Ossoli and had a child with him. Sadly, all three died in a shipwreck off Fire Island, New York, in 1850, while traveling back to the United States. Margaret Fuller's body was never found.

Fuller strongly believed in women's rights, especially their right to education and to have jobs. She also supported other social changes, like prison reform and ending slavery in the United States. Many other women's rights leaders, like Susan B. Anthony, said Margaret Fuller inspired them. However, some people during her time didn't support her. After her death, her importance seemed to fade for a while. Editors who prepared her letters for publishing even changed or removed parts of her work.

Contents

Margaret Fuller's Life Story

Early Years and Family

Sarah Margaret Fuller was born on May 23, 1810, in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. She was the first child of Congressman Timothy Fuller and Margaret Crane Fuller. She was named after her grandmothers, but by age nine, she preferred to be called "Margaret." The Margaret Fuller House, where she was born, is still standing today. Her father taught her to read and write when she was just three and a half years old. He gave her a very strict education, like what boys received at the time. He didn't let her read common "girly" books like etiquette guides. He started teaching her Latin when she was young, and soon she was translating simple passages from Virgil.

Margaret sometimes blamed her father's strict teaching for her childhood nightmares. During the day, she spent time with her mother, learning household tasks like sewing. In 1817, her brother William Henry Fuller was born, and her father became a representative in the United States Congress. For the next eight years, he spent several months each year in Washington, D.C. When she was ten, Margaret wrote a note that her father kept: "On 23 May 1810, was born one foredoomed to sorrow and pain, and like others to have misfortunes."

Fuller started school at the Port School in Cambridgeport in 1819. Then she went to the Boston Lyceum for Young Ladies from 1821 to 1822. In 1824, she was sent to the School for Young Ladies in Groton. She didn't like the idea at first. On June 17, 1825, 15-year-old Fuller attended a ceremony where the American Revolutionary War hero Marquis de Lafayette laid the cornerstone of the Bunker Hill Monument. Fuller wrote a letter to Lafayette, saying she hoped to make her name known, even as a woman. From a young age, Fuller felt she was an important thinker. She left the Groton school after two years and returned home at 16. At home, she studied classics and learned several modern languages. She also read world literature. She realized she was different from other young women her age. She wrote, "I have felt that I was not born to the common womanly lot."

Starting Her Career

Fuller loved to read and was known for translating German books. She helped bring German Romanticism to the United States. By her 30s, she was known as the best-read person in New England, male or female. She used her knowledge to give private lessons. Fuller wanted to earn a living through journalism and translation. Her first published work appeared in November 1834 in the North American Review. When she was 23, her father's law business failed, and the family moved to a farm in Groton. In 1835, she was asked to write for two different magazines. She published her first literary review in June, criticizing biographies of George Crabbe and Hannah More.

In the fall of 1835, she had a severe migraine with a fever. Fuller continued to have these headaches throughout her life. While she was still recovering, her father died from cholera on October 2, 1835. His death deeply affected her. She wrote, "My father's image follows me constantly." She promised to take care of her widowed mother and younger siblings. Her father had not left a will, so her uncles controlled his property. Fuller felt embarrassed by how her uncles treated the family.

Around this time, Fuller wanted to write a biography of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, but she felt she needed to travel to Europe to do it. Her father's death and her new family responsibilities made her give up this idea. In 1836, Fuller got a job teaching at Bronson Alcott's Temple School in Boston. She stayed there for a year. Then, in April 1837, she accepted a teaching job at the Greene Street School in Providence, Rhode Island. She earned a high salary of $1,000 a year. Her family sold the Groton farm, and Fuller moved with them to Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts.

On November 6, 1839, Fuller held the first of her "Conversations." These were discussions among local women who met in a Boston home. Fuller wanted to make up for the lack of education for women. The discussions focused on topics like art, history, mythology, literature, and nature. Fuller led the talks and wanted to help women answer "great questions" and encourage them to "question, to define, to state and examine their opinions." She asked her participants, "What were we born to do? How shall we do it?" In these Conversations, Fuller found intellectual friends among other women. Many important figures in the women's rights movement attended these meetings.

Editing The Dial

In October 1839, Ralph Waldo Emerson was looking for an editor for his transcendentalist magazine, The Dial. After others turned down the job, he offered it to Fuller. Emerson had met Fuller in Cambridge in 1835. Fuller accepted the offer to edit The Dial on October 20, 1839, and started work in early 1840. She edited the magazine from 1840 to 1842, but she was never paid her promised $200 annual salary. Because of her role, she quickly became known as one of the most important people in the transcendental movement. She was invited to George Ripley's Brook Farm, which was a community experiment. Fuller never officially joined Brook Farm but visited often.

In the summer of 1843, she traveled to Chicago, Milwaukee, Niagara Falls, and Buffalo, New York. While there, she met several Native Americans, including members of the Ottawa and the Chippewa tribes. She wrote about her experiences in a book called Summer on the Lakes, which she finished on her 34th birthday in 1844. Fuller used the library at Harvard College to research the Great Lakes region. She became the first woman allowed to use Harvard's library.

Fuller's essay "The Great Lawsuit" was first published in The Dial. When it was expanded and published as a separate book in 1845, it was called Woman in the Nineteenth Century. After finishing it, she wrote to a friend, "I had put a good deal of my true self in it." The book discussed the role of women in American democracy and Fuller's ideas for how things could improve. It has become one of the most important documents in American feminism. It is considered the first book of its kind in the United States.

Working for the New-York Tribune

Fuller left The Dial in 1844 partly because of her health and because the magazine had fewer and fewer subscribers. She moved to New York that autumn and joined Horace Greeley's New-York Tribune newspaper as a literary critic. She became the first full-time book reviewer in American journalism. By 1846, she was the newspaper's first female editor. Her first article, a review of essays by Emerson, appeared on December 1, 1844. At this time, the Tribune had about 50,000 subscribers, and Fuller earned $500 a year. She reviewed American and foreign books, concerts, lectures, and art shows. During her four years with the newspaper, she published over 250 articles. Most were signed with a "*" to show she wrote them. In these articles, Fuller wrote about art, literature, politics, and social issues like the struggles of slaves and women's rights. She also published poems.

Her Time in Europe

In 1846, the New-York Tribune sent Fuller to Europe, specifically England and Italy. She was their first female foreign reporter. She traveled from Boston to Liverpool in August. Over the next four years, she sent thirty-seven reports back to the Tribune. She interviewed many famous writers, including George Sand and Thomas Carlyle. She found Carlyle disappointing because of his old-fashioned political views. George Sand had been an idol of hers, but Fuller was disappointed when Sand chose not to run for the French National Assembly.

In England in the spring of 1846, she met Giuseppe Mazzini, an Italian who had been living in exile. Fuller also met Giovanni Angelo Ossoli, a Roman patriot. Fuller and Ossoli lived together in Florence, Italy. They later married, though the exact date is unclear. Their child, Angelo Eugene Philip Ossoli, was born in September 1848 and was nicknamed Angelino. Fuller told her mother about Ossoli and Angelino in August 1849. Her mother was happy for her daughter.

The couple supported Giuseppe Mazzini's movement to create a Roman Republic. This republic was declared on February 9, 1849. Ossoli fought to defend the city, while Fuller volunteered at two hospitals. When their side lost, they decided to leave Rome and move to Florence. In 1850, they planned to move to the United States. In Florence, they finally met Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Fuller used her experiences in Italy to start writing a book about the history of the Roman Republic. She hoped it would be her most important work.

Her Death

In early 1850, Fuller wrote to a friend that she felt a "vague expectation of some crisis." A few days later, Fuller, Ossoli, and their child began a five-week trip back to the United States. They were on a ship called the Elizabeth, which was carrying marble. They set sail on May 17. At sea, the ship's captain died of smallpox. Angelino also got sick but recovered.

On July 19, 1850, around 3:30 a.m., the ship hit a sandbar less than 100 yards from Fire Island, New York. Many passengers and crew members left the ship. People on the beach arrived with carts, hoping to salvage cargo that washed ashore. No one tried to rescue the people on the ship, even though they were very close to shore. Most people tried to swim to shore. Fuller, Ossoli, and Angelino were among the last on the ship. A large wave swept Ossoli overboard. A crewman said Fuller could not be seen after the wave passed.

Henry David Thoreau went to New York to search the shore, but neither Fuller's body nor her husband's was ever found. Angelino's body washed ashore. Few of their belongings were found, except some of the child's clothes and a few letters. Fuller's important manuscript about the Roman Republic was also lost. A memorial to Fuller was built on the beach at Fire Island in 1901. A cenotaph (a monument for someone buried elsewhere) for Fuller and Ossoli, where Angelino is buried, is in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

After her death, many of Margaret Fuller’s papers were collected. In February 1852, The Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli was published. It was edited by Emerson and others, but much of her work was changed or removed. The editors believed that public interest in Fuller would not last long. For a time, it was a best-selling biography.

Margaret Fuller's Beliefs

Fuller was an early supporter of feminism. She especially believed that women should have access to education. She thought that once women had equal educational rights, they could then push for equal political rights. She argued that women should be able to choose any job they wanted, instead of only traditional "feminine" roles like teaching. She once said, "If you ask me what office women should fill, I reply—any... let them be sea captains if you will." She had great faith in women but doubted that a woman in her time would create a lasting work of art or literature. Fuller also warned women to be careful about marriage and not to become too dependent on their husbands. She wrote, "I wish woman to live, first for God's sake." By 1832, she had decided to stay single.

Fuller also questioned the clear line between male and female. She believed that both male and female qualities were present in every person. She suggested that women had two parts: an intellectual side (which she called the Minerva) and a "lyrical" or "Femality" side (the Muse). She admired the ideas of Emanuel Swedenborg, who believed men and women shared "an angelic ministry," and Charles Fourier, who placed "Woman on an entire equality with Man."

Fuller also supported changes in all parts of society, including prison reform. In October 1844, she visited Sing Sing prison and interviewed the women prisoners. She even stayed overnight. Fuller was also concerned about homeless people and those living in extreme poverty, especially in New York. She realized that Native Americans were unfairly treated by white people. She believed Native Americans were an important part of American heritage. She also supported the rights of African-Americans, calling slavery a "cancer." She suggested that those who supported ending slavery should use the same ideas when thinking about women's rights.

Fuller agreed with the transcendental idea of individual well-being, but she didn't like being called a transcendentalist. She criticized people like Emerson for focusing too much on individual improvement and not enough on social change. Like other members of the Transcendental Club, she believed in the possibility of change. However, unlike others in the movement, her ideas were not based on religion. Fuller sometimes went to Unitarian churches, but she didn't fully identify with that religion.

Some people have said Fuller was a vegetarian because she criticized the killing of animals for food in her book Woman in the Nineteenth Century. However, some biographers say she didn't fully support vegetarianism because she disliked the extreme views of some vegetarians.

Selected Works

- Summer on the Lakes (1844)

- Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845)

- Papers on Literature and Art (1846)

Books Published After Her Death

- Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1852)

- At Home and Abroad (1856)

- Life Without and Life Within (1858)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Margaret Fuller para niños

In Spanish: Margaret Fuller para niños