Indian removal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Indian removal |

|

|---|---|

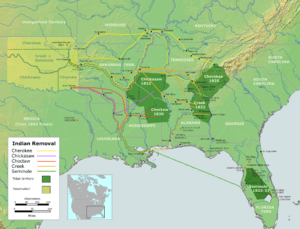

Routes of southern removals

|

|

| Location | United States |

| Date | 1830–1847 |

| Target | Native Americans in the eastern United States |

|

Attack type

|

Population transfer, ethnic cleansing, genocide |

| Deaths | 8,000+ (lowest estimate) |

| Assailants | United States |

| Motive | Expansionism |

Indian removal was a policy by the U.S. government that forced many Native American tribes to leave their homes. These tribes lived in the eastern United States. They were made to move to lands west of the Mississippi River, mainly to an area called Indian Territory (which is now mostly Oklahoma).

The main law that allowed this removal was the Indian Removal Act. Andrew Jackson signed this law in 1830. Most of the forced removals happened during the time Martin Van Buren was president. After 1831, about 60,000 people from the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forced to move. Thousands of them died during this journey, which is now known as the Trail of Tears.

This policy was popular among white settlers. It grew out of conflicts between European settlers and Native Americans that had been happening since the 1600s. These conflicts became worse in the early 1800s as white settlers moved west. Many believed in "manifest destiny", which was the idea that Americans were meant to expand across the continent. Today, historians often describe Indian removal as a form of ethnic cleansing (forcing a group out of an area) or even genocide (trying to destroy a group).

Contents

Early American Leaders and Native Americans

In the early days of the United States, leaders discussed how to treat Native Americans. Should they be seen as individuals or as separate nations?

The Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence was written in 1776. It mentioned Native Americans as "merciless Indian Savages". This shows a common, negative view held by many white people at that time.

Benjamin Franklin's Ideas

In 1775, Benjamin Franklin suggested a "lasting alliance" with Native American tribes, especially the Iroquois Confederacy. He wanted their lands to be protected and not taken without fair agreements. He also wanted people to live among them to prevent unfair trade.

First Laws by Congress

The Confederation Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance in 1787. This law said that Native American "property, rights, and liberty" should be protected. The U.S. Constitution (1787) also gave Congress the power to manage trade with Indian tribes. In 1790, Congress passed the Indian Nonintercourse Act. This law was meant to protect the land rights of recognized tribes.

George Washington's Approach

President George Washington spoke to the Seneca Nation in 1790. He promised to uphold their "just rights". In 1792, he met with 50 tribal chiefs to strengthen friendship. Washington believed the U.S. government needed to act peacefully towards Native Americans. He said that if raids by Native Americans were to stop, then raids by American settlers must also stop.

Thomas Jefferson's Views

Thomas Jefferson believed Native Americans were equal to white people in body and mind. He hoped they would mix with European Americans and become one people. As president, he offered U.S. citizenship to some tribes. He also suggested offering them credit to help with trade.

However, Jefferson also had other ideas. He wanted Native Americans to change from hunting to farming. He thought this would make them depend on white Americans for goods. This might also make them more likely to give up their land or move west of the Mississippi River. In 1803, he wrote that if any tribe fought against the U.S., their entire land could be taken. They would then be forced across the Mississippi River.

Jefferson also spoke about protecting Native Americans from wrongs by white people. In 1819, a treaty offered citizenship and land to Cherokees living east of the Mississippi. The idea of trading land, where Native Americans would give up eastern lands for western lands, was first suggested by Jefferson in 1803. This idea was later included in the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

John C. Calhoun's Plan

Under President James Monroe, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun created the first plans for Indian removal. In 1825, Monroe asked for the creation of new territories for Native Americans west of the Mississippi. The idea was that Native Americans would willingly trade their eastern lands for these new western lands.

However, the state of Georgia refused to agree to these plans. The Cherokee Nation then wrote its own constitution in 1827. They declared themselves an independent nation. Georgia argued that it would not allow a separate nation within its borders. When Andrew Jackson became president, he strongly supported forcing Native Americans to move west.

Opposition to Removal

Even though many people supported Indian removal, others strongly opposed it. They argued it was wrong both legally and morally. Ralph Waldo Emerson, a famous writer, wrote a public letter in 1838. He called the treaty that forced the Cherokee to move a "sham treaty" and an act of "fraud and robbery". He urged President Martin Van Buren to stop the removal. Many other people and groups across the country also spoke out against the policy.

Native American Responses to Removal

Native American groups tried to protect their lands and way of life. They created their own governments and legal codes. They sent leaders to Washington to negotiate treaties. They hoped that by adopting some American ways, they could stop the removal policy.

However, Native American nations had different ideas about removal. Most wanted to stay on their lands. But some believed that moving to a non-white area was the only way to keep their independence and culture. The U.S. government sometimes used these differences to make treaties with smaller groups within a tribe. These treaties were often not supported by most of the tribe's people. Once a treaty was approved by Congress, the government could use military force to remove tribes if they didn't move by the agreed date.

The Indian Removal Act

When Andrew Jackson became president in 1829, his government took a very firm stance on Indian removal. Jackson stopped treating Native American tribes as separate nations. He wanted all tribes east of the Mississippi to move to reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). After much debate, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. Jackson signed it into law on May 30, 1830.

This act allowed the president to negotiate land-exchange treaties. It did not directly force tribes to move, but it set the stage for forced removals. Most of the Five Civilized Tribes—the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee—lived east of the Mississippi at this time.

Choctaw Removal

On September 27, 1830, the Choctaw signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. They were the first Native American tribe to be removed. This agreement was one of the largest land transfers between the U.S. government and Native Americans that didn't result from war. The Choctaw gave up their traditional lands in Mississippi. When they reached Little Rock, one chief called their journey a "trail of tears and death".

In 1831, a French writer named Alexis de Tocqueville saw a group of Choctaw during a very cold winter. They were exhausted and heading to the Mississippi River. He wrote that the scene felt like "ruin and destruction" and made his heart ache. He asked a Choctaw why they were leaving their country. The Choctaw replied, "To be free."

Cherokee Removal

The Indian Removal Act was often misused by government officials. A small group of twenty Cherokee members signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, even though the main tribal leaders did not agree. Most Cherokees later blamed this treaty for their forced relocation in 1838. About 4,000 Cherokees died during this march, which is known as the Trail of Tears.

The Cherokee Nation took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Court said Native American tribes were not foreign nations and could not sue in U.S. courts. However, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that individual states had no power over American Indian affairs.

The state of Georgia ignored the Supreme Court's ruling. White settlers and land speculators still wanted Indian lands. Georgia even passed a law forbidding white people from living on Indian territory without a state license.

Seminole Resistance

The Seminole people in Florida refused to leave their lands in 1835. This led to the Second Seminole War. Osceola was a Seminole leader who fought against the removal. He and his group used surprise attacks in the Everglades to defeat the U.S. Army many times. In 1837, Osceola was captured unfairly while trying to negotiate peace. He later died in prison from illness. The war caused over 1,500 U.S. deaths and cost the government $20 million. Some Seminole moved deeper into the Everglades, while others were forced west.

Muskogee (Creek) Removal

After earlier treaties, the Muscogee (Creek) people were left with a small piece of land in Alabama. In 1832, the Creek council signed the Treaty of Cusseta. This treaty gave their remaining lands east of the Mississippi to the U.S. and agreed to move to Indian Territory. Most Muscogee were removed during the Trail of Tears in 1834.

Even though some Creeks had not fought in a war against the U.S., they were still forced to move. About 16,000 Creeks were divided into groups and sent to Fort Gibson. They faced very difficult conditions, including bad roads, harsh weather, and a lack of water. Many died during the journey. For example, one group of 2,318 Creeks had 78 deaths.

President Andrew Jackson spoke to the Creek Nation in 1829. He told them that they and his "white children" were too close to live in peace. He said their hunting grounds were gone and many would not farm. He advised them to move beyond the Mississippi River, where he had provided a large country for them. He promised they would live there in peace and plenty forever.

Chickasaw Removal

Unlike other tribes, the Chickasaw were supposed to receive $3 million from the United States for their lands. They bought land from the Choctaw in 1836 for $530,000. Most Chickasaw moved in 1837 and 1838. However, the U.S. government did not pay the Chickasaw the $3 million it owed them for nearly 30 years.

Aftermath of Removals

The Five Civilized Tribes were resettled in the new Indian Territory. Some Native American nations resisted the forced migration more strongly. A few groups stayed behind, forming tribes like the Eastern Band of Cherokee in North Carolina and the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

Removals in Different Regions

Removals in the North

Tribes in the Old Northwest were smaller and more scattered. So, their removal happened in many smaller steps. After the Northwest Indian War, much of Ohio was taken from Native nations in 1795. Tribes like the Lenape (Delaware), Kickapoo, and Shawnee were removed from Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio in the 1820s. The Potawatomi were forced out of Wisconsin and Michigan in 1838.

In 1832, the Sauk leader Black Hawk led some Sauk and Fox people back to their lands in Illinois. The U.S. Army defeated them in the Black Hawk War. The Sauk and Fox were then moved to present-day Iowa.

The Senecas in New York also faced removal. In 1838, they agreed to give up most of their land in New York for land in Indian Territory. However, the lands were sold unfairly by government officials. The Senecas sued for justice. The case was not settled until 1898, when the U.S. government paid them nearly $2 million in compensation.

Removals in the South

| Nation | Population before removal | Treaty and year | Major emigration | Total removed | Number remaining | Deaths during removal | Deaths from warfare |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choctaw | 19,554 + White citizens of the Choctaw Nation + 500 Black slaves | Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830) | 1831–1836 | 15,000 | 5,000–6,000 | 2,000–4,000+ (cholera) | none |

| Creek (Muscogee) | 22,700 + 900 Black slaves | Cusseta (1832) | 1834–1837 | 19,600 | Several hundred | 3,500 (disease after removal) | Unknown (Creek War of 1836) |

| Chickasaw | 4,914 + 1,156 Black slaves | Pontotoc Creek (1832) | 1837–1847 | over 4,000 | Several hundred | 500–800 | none |

| Cherokee | 16,542 + 201 married White + 1,592 Black slaves | New Echota (1835) | 1836–1838 | 16,000 | 1,500 | 2,000–4,000 | none |

| Seminole | 3,700–5,000 + fugitive slaves | Payne's Landing (1832) | 1832–1842 | 2,833–4,000 | 250–500 | 700 (Second Seminole War) |

Changing Views on the Policy

Over time, how people view Indian removal has changed a lot. In the past, many accepted it because of ideas like manifest destiny. Today, people have a much more serious view. Historians have described these removals as ethnic cleansing (forcing a group out of their homes) or even genocide (actions meant to destroy a group). Historian David Stannard has called it genocide.

Andrew Jackson's Reputation

Andrew Jackson's reputation has been negatively affected by his actions towards Native Americans. Some historians who admired his strong leadership used to ignore the Indian Removal. In the 1970s, historians like Michael Rogin and Howard Zinn strongly criticized Jackson for this policy. Zinn called him an "exterminator of Indians." However, other historians argue that Jackson's policies do not meet the full definition of physical or cultural genocide.

|

See also

In Spanish: Deportación de los indios de los Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Deportación de los indios de los Estados Unidos para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |