Cherokee Nation facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cherokee Nation

Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

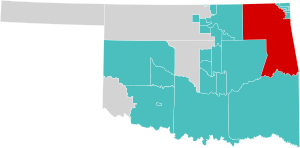

Location (red) in the U.S. state of Oklahoma

|

|||

| Pre-1794 Cherokees | Pre-Columbian era | ||

| Cherokee Nation (1794-1907) | 1794–1907 | ||

| Constitution | September 6, 1839 | ||

| Federal Dissolution | November 16, 1907 | ||

| Tribal General Convention convened | August 8, 1938 | ||

| New Constitution Ratified | June 26, 1976 | ||

| Reservation Reconstituted | July 9, 2020 | ||

| Capital | Tahlequah | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Tribal Council | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 6,963 sq mi (18,030 km2) | ||

| • Land | 6,694 sq mi (17,340 km2) | ||

| • Water | 269 sq mi (700 km2) | ||

| Population

(2018)

|

|||

| • Total | 360,589 | ||

| Demonym(s) | Cherokee | ||

| Time zone | UTC–06:00 (CST) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–05:00 (CDT) | ||

| Area code(s) | 918 and 539 | ||

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ, Tsalagihi Ayeli), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It was formed in the 20th century. The Nation includes people whose families moved from the Southeast to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Many were forced to move on the Trail of Tears. The tribe also includes descendants of Cherokee Freedmen, Absentee Shawnee, and Natchez Nation members.

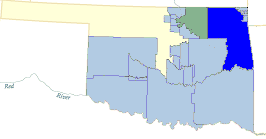

As of 2018, over 360,000 people were officially part of the Cherokee Nation. About 240,000 of them live in Oklahoma. The main office of the Cherokee Nation is in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Their tribal area covers 14 counties in northeastern Oklahoma. These counties are Adair, Cherokee, Craig, Delaware, Mayes, McIntosh, Muskogee, Nowata, Ottawa, Rogers, Sequoyah, Tulsa, Wagoner, and Washington.

Contents

History of the Cherokee Nation

Early Challenges and Changes

From 1898 to 1906, the U.S. government tried to end the Cherokee Nation's government. This was done to prepare for Indian Territory to become the new state of Oklahoma. After 1906, the tribal government's structure was not clear for many years.

After the Cherokee Nation's government was dissolved in the early 1900s, the U.S. government started appointing chiefs. These appointed chiefs often served for very short times. They were sometimes called "Chief for a Day." Their main task was often to sign treaties that gave away more land.

Rebuilding the Modern Cherokee Nation

In the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt wanted to help tribes rebuild their governments. He supported the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. This law encouraged tribes to create their own governments and write constitutions. On August 8, 1938, the Cherokee Nation held a meeting in Fairfield, Oklahoma to elect a Chief. They chose J. B. Milam, and President Roosevelt confirmed this in 1941.

W. W. Keeler was appointed chief in 1949. Later, under President Richard Nixon's policy of self-determination, the Cherokee Nation was able to fully rebuild its government. The people elected W. W. Keeler as chief. He was also the president of Phillips Petroleum. After Keeler, Ross Swimmer became chief.

In 1975, the tribe wrote a new constitution. It was approved on June 26, 1976. This constitution helped the tribe use its legal name, Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, in court cases.

In 1985, Wilma Mankiller made history by becoming the first female chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Growth and Community Support

The modern Cherokee Nation has grown a lot economically. They have many businesses, real estate, and farming interests. This helps create money for economic growth and community programs.

The Cherokee Nation has built health clinics across Oklahoma. They support community development, build roads and bridges, and create learning centers. They also teach the practice of Gadugi, which means working together for the community. The Nation has also brought back language immersion programs for children. They are a strong economic and political force in Eastern Oklahoma. The tribe now runs the W. W. Hastings Hospital in Tahlequah.

The Cherokee Nation hosts the Cherokee National Holiday every year on Labor Day weekend. This event brings 80,000 to 90,000 Cherokee people to Tahlequah for celebrations. The Nation also publishes the Cherokee Phoenix, a tribal newspaper. This newspaper has been running almost continuously since 1828. It publishes in both English and the Cherokee syllabary.

The Cherokee Nation helps fund groups that preserve Cherokee culture, like the Cherokee Heritage Center. This center has exhibits that show what life was like in an ancient Cherokee village and a turn-of-the-century village. It also has the Cherokee Family Research Center for people interested in their family history. The Cherokee Heritage Center is also home to the Cherokee National Museum.

The Cherokee Nation supports film festivals in Tahlequah and takes part in the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. The Nation owns Cherokee Nation Businesses, a company that earns money to fund services for Cherokee citizens.

Economy and Business

The Cherokee Nation owns Cherokee Nation Businesses. This company has businesses in many areas, including gaming, construction, aerospace, manufacturing, technology, real estate, and healthcare. The Nation also has its own housing authority. They even issue special vehicle and boat tags for tribal members.

The Cherokee Nation's businesses have a big impact on Oklahoma's economy. They contribute over $1 billion each year and support more than 13,500 jobs for both Cherokee and non-Cherokee people. This growth has brought a lot of economic success and opportunities for its citizens.

Tribal Membership

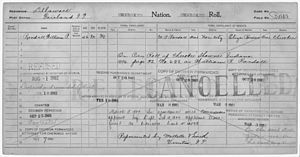

To be a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, a person needs to have a direct ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls. These rolls were official lists created by the U.S. government. Race or how much "Cherokee blood" a person has does not affect their eligibility. The tribe has members with African, Latino, Asian, white, and other backgrounds. Members of the Natchez Nation and other southeastern tribes joined the Cherokee Nation in the 1700s.

Connecting with Members Outside Oklahoma

Two tribal council members represent Cherokee citizens who live outside the 14-county area in Oklahoma. The tribe has also set up eleven satellite communities in places where many Cherokee Nation citizens live. These communities help members connect with Cherokee culture and get more involved in tribal politics. These communities are in states like Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Florida, and central Oklahoma.

Relationship with Other Cherokee Groups

Many groups claim to be Cherokee tribes and seek official recognition from the U.S. government. However, only three groups are federally recognized today. These are the Cherokee Nation, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians.

The Cherokee Nation encourages groups that focus on Cherokee heritage and culture. But they are concerned about groups that try to gain money by falsely claiming to be Cherokee tribes. The three federally recognized tribes state that only they have the legal right to call themselves Cherokee Indian Tribes.

In 2008, the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians passed a resolution. This resolution opposed the recognition of new "fabricated" Cherokee tribes. They committed to working with authorities to stop any group that falsely claims to be a Cherokee government. They also asked that no public money be given to groups that are not federally recognized.

The resolution also encouraged people not to claim Cherokee ancestry to boost their careers if they are not members of a federally recognized tribe. The United Keetoowah Band did not sign this resolution. The Cherokee Nation understands that there are people of Cherokee descent in other states like Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Texas. These people have Cherokee ancestors but are not considered members of the Cherokee Nation.

Current Activities and Recent Events

Protecting the Environment

Today, the Cherokee Nation is a leader in protecting the environment. Since 1992, the Nation has led the Inter-Tribal Environmental Council (ITEC). ITEC's goal is to protect the health of American Indians, their natural resources, and their environment. They do this by providing technical support, training, and environmental services. More than 40 tribes from Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas are part of ITEC.

As of 2014, the Cherokee Seed Project offers special seeds to Cherokee Nation members. These include two types of corn, two kinds of beans (like "Trail of Tears" beans), two gourds, and medicinal tobacco.

Cherokee Nation Leadership Challenges

In 1997, there was a disagreement within the Cherokee Nation government. The Principal Chief, Joe Byrd, had a conflict with the tribe's judicial branch. This led to a serious situation where Byrd's private security force took control of the Cherokee Nation Courthouse.

The U.S. government at first did not get involved. However, the State of Oklahoma saw that Byrd's actions broke state laws. Eventually, Byrd was required to meet with U.S. officials and reopen the courts. He finished his term as chief. In 1999, Byrd lost the election for Principal Chief to Chad Smith.

New Constitution and Changes

A new constitution was written in 1999. It allowed voters to remove officials from office and changed how the tribal council worked. It also removed the need for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to approve changes to the constitution. After some discussions, the new constitution was approved in 2003.

To avoid future problems, the Cherokee Nation voted to amend its 1975/1976 Constitution. This change removed the need for U.S. government approval for constitutional amendments. As of 2007, the BIA agreed that the Cherokee Nation could amend its constitution without their approval.

Cherokee Freedmen Citizenship

The Cherokee Freedmen are descendants of African Americans who were enslaved by Cherokee citizens before the American Civil War. After the Civil War, a treaty in 1866 guaranteed them Cherokee citizenship. This was part of the peace agreement with the U.S. government.

Over time, there were legal challenges about their citizenship. In 2006, the Cherokee Nation Judicial Appeal Tribunal ruled that Freedmen were eligible for citizenship. This ruling was based on their historical citizenship since 1866, not on having "Cherokee blood."

However, in 2007, a special election was held to change the constitution. This change would limit citizenship to only those with an ancestor on the "Cherokee by blood" part of the Dawes Rolls. This would exclude many Freedmen descendants. The vote passed, but it caused a lot of debate. The U.S. government and civil rights groups raised concerns about fairness.

In 2011, a tribal court ruled that the 2007 election was unconstitutional because Freedmen were not allowed to vote. The Cherokee Supreme Court later upheld the results of the 2007 election. This led to more legal action and discussions with the U.S. government. Eventually, an agreement was reached to allow Freedmen to vote while the cases continued.

Education and Language Preservation

The Cherokee Nation has a 10-year plan to save the Cherokee language. This plan includes creating new fluent speakers through school immersion programs. It also encourages families to use the language at home. The goal is for 80% or more of the Cherokee people to be fluent in the language within 50 years. The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $3 million to open schools, train teachers, and create language learning materials.

The Kituwah Preservation & Education Program (KPEP), started in 2006, focuses on language immersion for young children. It also creates cultural resources and community programs for adults. There is a Cherokee language immersion school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, for students from pre-school to eighth grade.

Several universities offer Cherokee as a second language, including the University of Oklahoma, Northeastern State University, and Western Carolina University. Western Carolina University works with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to promote the language through its Cherokee Studies program.

In 2020, the Cherokee Nation announced plans for the new Durbin Feeling Language Center in Tahlequah. This center will bring all the tribe's language programs together. It will also have houses nearby for native speakers to live in, helping them interact with others at the center.

Relationships with Other Tribes

The Cherokee Nation works with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians on many programs. These include cultural exchanges and joint meetings between their tribal councils. These meetings address issues that affect all Cherokee people.

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians once voted to meet with the Cherokee Nation to improve their relationship. However, the Chief of the Cherokee Nation at the time, Chad Smith, did not approve the meeting.

The Delaware Tribe of Indians (Lenape) became part of the Cherokee Nation in 1867. In 2009, they gained independent federal recognition as a separate tribe. Similarly, the Shawnee Tribe also separated from the Cherokee Nation and became federally recognized.

The Cherokee Nation strongly opposes the federal or state recognition of other groups claiming to be Cherokee. They believe this could harm the sovereignty of existing tribes.

Notable Cherokee People

Here are some well-known people who are citizens of the Cherokee Nation:

- Bud Adams (1923–2013), a businessman who owned the Tennessee Titans football team.

- Tommy Allsup, a musician.

- Bill John Baker, a former Principal Chief.

- Martha Berry, a beadwork artist.

- Roy Boney Jr. (born 1978), an artist and language advocate.

- Dylan Bundy, a baseball pitcher.

- Joe Byrd, a former Principal Chief.

- Brad Carson (born 1967), a former Oklahoma congressman.

- Admiral Joseph J. Clark (1893–1971), the highest-ranking Native American in the U.S. military.

- Mike Dart (born 1977), a basket weaver.

- Mavis Doering (1929–2007), a basket weaver.

- Jerry C. Elliott (born 1943), a NASA engineer who helped save the Apollo 13 astronauts.

- Joseph L. Erb (born 1974), an artist and Cherokee language advocate.

- Angel Goodrich (born 1990), a WNBA basketball player.

- Yvette Herrell (born 1964), a New Mexico congresswoman.

- W. W. Keeler (1908–1987), a former Principal Chief.

- Litefoot, a rapper and actor.

- Wilma Mankiller (1945–2010), the first female Principal Chief and an author.

- Barbara McAlister (born 1941), an opera singer.

- J. B. Milam (1884–1949), a former Principal Chief.

- Markwayne Mullin (born 1977), an Oklahoma congressman.

- Lloyd Kiva New (1916–2002), an artist and fashion designer.

- Will Rogers Jr. (1911–1993), a journalist and entertainer.

- Sonny Sixkiller (born 1951), a football player.

- Chad Smith, a former Principal Chief.

- Hastings Shade (1941–2010), a traditionalist and artist.

- Wes Studi (born 1947), an actor and musician.

- Kimberly Teehee (born 1969/70), a political advisor.

- Kay WalkingStick (born 1935), a painter.

- Madison Whitekiller, a former Junior Miss Cherokee and Miss Cherokee.

- Tommy Wildcat, a Native American flutist.

Population and Citizenship

As of 2018, the Cherokee Nation had 360,589 citizens. These citizens live in every U.S. state. In 2018, about 240,417 lived in Oklahoma, 22,124 in California, and 18,406 in Texas. By 2021, the number of enrolled citizens reached 400,000. This makes the Cherokee Nation the second largest tribe, after the Navajo Nation. About 140,000 citizens live within the Cherokee Nation's reservation area.

Who Can Be a Citizen?

To be a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, you need to have a direct ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls. This ancestor could be listed as a Cherokee Indian or as one of the Cherokee Freedmen. The tribe includes members with different backgrounds, such as African, Latino, Asian, and European ancestry. For example, some members who are descendants of Cherokee Freedmen may be mostly or entirely African American.

Members of the Natchez Nation and other southeastern tribes joined the Cherokee Nation in the 1700s. Unlike the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, the Cherokee Nation does not use "blood quantum" (a measure of Native American ancestry) for citizenship. Race is also not a factor, although it was used when the Dawes Rolls were created.

Some scholars have discussed how citizenship rules have changed over time. In the past, Cherokee identity was often based on family and clan relationships. This meant people could be fully Cherokee without having a specific amount of Cherokee ancestry. The use of the Dawes Rolls for citizenship is different from these older ways of defining who is Cherokee.

Cherokee Language Efforts

The Cherokee Nation has a 10-year plan to keep the Cherokee language alive. This plan focuses on teaching children the language through immersion schools. It also encourages communities to use the language at home. The goal is for a large percentage of Cherokee people to speak the language fluently in the future. The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested money to open schools, train teachers, and create learning materials.

The Kituwah Preservation & Education Program (KPEP), located in North Carolina, also has language immersion programs for young children. They also create cultural resources and community programs for adults. There is a Cherokee language immersion school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, for students up to eighth grade.

Several universities offer Cherokee language classes, including the University of Oklahoma, Northeastern State University, and Western Carolina University. Western Carolina University works with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to help preserve and restore the language. They offer classes about the language and culture of the Cherokee people.

In 2020, the Cherokee Nation announced plans for the new Durbin Feeling Language Center in Tahlequah. This center will bring together all the tribe's language programs. It will also have homes nearby for native speakers, encouraging them to interact with others at the center.

Images for kids

-

Example of a Cherokee census card for Fairland, Oklahoma from the first few years of the 20th century.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |