Cherokee freedmen controversy facts for kids

The Cherokee Freedmen controversy was a big disagreement between the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma and the descendants of people who were once enslaved by the Cherokee. This fight was all about who could be a member of the Cherokee Nation. It led to many legal battles that lasted from the late 1900s until August 2017.

Before the American Civil War, the Cherokee and other Native American nations in the Southeast, called the Five Civilized Tribes, owned African-American slaves. These slaves worked for them. In 1860, about 2,511 slaves were owned by Cherokee Nation members. Slave labor helped wealthy Cherokee leaders, like Chief John Ross, rebuild their homes and lives after being forced to move to Indian Territory. After the Civil War, the Cherokee Freedmen were set free. They were allowed to become citizens of the Cherokee Nation. This was part of a special agreement called the Reconstruction Treaty made with the United States in 1866.

However, in the early 1980s, the Cherokee Nation changed its rules for citizenship. They said that only people whose ancestors were listed on the "Cherokee By Blood" section of the Dawes Rolls could be citizens. This change meant that many descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen lost their citizenship and voting rights.

On March 7, 2006, the Cherokee Supreme Court decided that this new rule was against their laws. They said Freedmen descendants should be allowed to join the Cherokee Nation. But, in a special election on March 3, 2007, a new rule was passed. This rule again kept out Freedmen descendants unless they met the "Cherokee by blood" requirement. The Cherokee Nation District Court then said this 2007 rule was invalid on January 14, 2011. But this decision was overturned by the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court on August 22, 2011.

This ruling also stopped Freedmen descendants from voting in an important election for Principal Chief. Because of this, the Department of Housing and Urban Development stopped $33 million in funds for the Cherokee Nation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs also wrote a letter saying they disagreed with the ruling. After this, the Cherokee Nation, Freedmen descendants, and the U.S. government agreed in federal court to let the Freedmen descendants vote.

The Cherokee Nation filed a lawsuit in early 2012. But Freedmen descendants and the United States Department of the Interior filed their own lawsuits in July 2012. The U.S. Court of Appeals said that tribal nations have the right to govern themselves. However, they also said these cases had to be combined because they involved the same groups. On May 5, 2014, the first hearing about the actual issues of the case happened. On August 30, 2017, the U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the Freedmen descendants. This gave them full rights as citizens in the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Nation has accepted this decision, which mostly ended the dispute. In 2021, the Cherokee Nation's Supreme Court even ruled to remove the words "by blood" from its constitution. These words had been used to exclude Black people whose ancestors were enslaved by the tribe from getting full Cherokee Nation citizenship rights.

Contents

- Who are the Cherokee Freedmen?

- History of the Controversy

- Recent Events (2004-2017)

- Other Media About the Controversy

- See also

Who are the Cherokee Freedmen?

The term "Freedmen" refers to formerly enslaved people and their children after slavery ended in the United States. In this case, "Cherokee Freedmen" means the African-American men and women who were enslaved by the Cherokee. This includes those who were enslaved before and after the Trail of Tears and the American Civil War. It also includes the children of these formerly enslaved people and those born from marriages between formerly enslaved African Americans and Cherokee tribal members.

After they were freed and became citizens, the Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants faced challenges in being fully accepted. Many Freedmen were active in the tribe. They voted in elections, ran businesses, and knew Cherokee traditions and language. Some Cherokee Freedmen even served on the tribal council. Joseph Brown was the first Cherokee Freedman elected to the council in 1875. Joseph "Stick" Ross, who was born into slavery, became a well-known civic leader. He had several businesses and even a mountain named after him. His great-grandson, Leslie Ross, said that Stick Ross knew sign language, spoke Cherokee and Seminole, and was a trapper, farmer, rancher, and even a sheriff.

The role of Freedmen in the tribe grew by the time of the Dawes Commission. This commission convinced the Cherokee and other Five Civilized Tribes to divide their tribal land into smaller plots for individual families. The Cherokee Freedmen were listed on the Dawes Rolls, which were records created by the Dawes Commission to list citizens in Indian Territory. When tribal governments were ended by the Curtis Act of 1898, Freedmen and other Cherokee citizens became U.S. citizens. Oklahoma became a state in 1907. After the Cherokee Nation restarted its government in 1970, Freedmen participated in the 1971 tribal elections. This was the first election held by the Cherokee since the Curtis Act.

Some descendants of Cherokee Freedmen still feel a strong connection to their heritage. However, others have become unsure about their ties. This is because they were excluded from the tribe for many years. They no longer feel that being identified as Cherokee is essential to who they are.

History of the Controversy

Slavery Among the Cherokee People

Slavery existed in Cherokee society even before Europeans arrived. The Cherokee often enslaved enemies captured during wars with other tribes. They saw slavery as a temporary status, and enslaved people could sometimes be released or adopted into the tribe. However, during the colonial era, settlers from Carolina bought or forced Cherokees into slavery in the late 1600s and early 1700s.

From the late 1700s to the 1860s, the Five Civilized Tribes in the American Southeast started to adopt some Euro-American customs. Some Cherokee men became wealthy landowners and bought enslaved African Americans. These enslaved people worked in fields, homes, and various trades. In 1809, a census counted 583 "Negro slaves" owned by Cherokee people. By 1835, this number grew to 1,592 slaves. More than seven percent of Cherokee families owned slaves, which was a higher percentage than in the Southern U.S. generally.

Cherokee slaveowners took their slaves with them on the Trail of Tears. This was the forced journey of Native Americans from their homelands to Indian Territory. The Cherokee were the largest tribe moved to Indian Territory and owned the most enslaved African Americans. Important Cherokee slaveowners included families like Joseph Lynch, Joseph Vann, Major Ridge, Stand Watie, Elias Boudinot, and Principal Chief John Ross.

Slavery was less common among full-blood Cherokee people. They often lived in more isolated areas away from European-American influence. However, both full-blood and mixed-blood Cherokee became slaveowners. One example was Tarsekayahke, also known as "Shoe Boots." He had two African-American slaves, including a woman named Doll. Shoe Boots later had three children with Doll.

The Cherokee tribe had a matrilineal system. This meant that family lines and inheritance were passed down through the mother. Children were considered part of their mother's family and clan. Because Shoe Boots' children were born to a slave, they were also considered slaves. This was similar to slave laws in the U.S., known as partus sequitur ventrem. For these children to be fully accepted into the tribe, they would usually need to be adopted by a Cherokee woman and her clan.

On October 20, 1824, Shoe Boots asked the Cherokee National Council to free his three children and recognize them as free Cherokee citizens. He said he wanted them to be free citizens of the nation. He did not want them to be treated as property. On November 6, 1824, his request was granted. That same year, the Council passed a law that stopped marriages between Cherokee people and slaves or free Black people. But in 1825, they passed a law giving automatic Cherokee citizenship to mixed-race children born to white women and their Cherokee husbands. This was to help the children of male leaders who were marrying white women.

Even though Shoe Boots' children were freed, the Council told him to end his relationship with Doll. But he had two more sons with her, twins named Lewis and William, before he died in 1829. After his death, his sisters inherited these two sons as property. They tried to get the council to free the twins, but they were not successful.

Slavery in Cherokee society was often similar to slavery in European-American society. The Cherokee created their own slave laws that treated enslaved people and free Black people unfairly. Cherokee law banned marriage between Cherokee and Black people. African Americans who helped slaves were punished with 100 lashes. Black people were not allowed to hold public office, carry weapons, vote, or own property. It was also illegal to teach Black people to read or write.

After being moved to Indian Territory, enslaved African Americans tried to escape and revolt many times. In the Cherokee Slave Revolt of 1842, many enslaved African Americans left their plantations near Webbers Falls, Oklahoma to escape to Mexico. They were captured by a Cherokee militia. On December 2, 1842, the Cherokee National Council passed a law that banned all free Black people from the Cherokee Nation by January 1843. In 1846, about 130-150 African slaves escaped from Cherokee territory. Most were captured by a group of Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole slaveowners.

Civil War and End of Slavery

By 1861, the Cherokee Nation held about 4,000 Black slaves. During the American Civil War, the Cherokee Nation was divided. Some supported the Union, and others supported the Confederate States of America. Principal Chief John Ross first tried to keep the Cherokee neutral. In July 1861, Ross tried to unite the Five Civilized Tribes to stay neutral, but he failed.

Ross and the Cherokee council later agreed to side with the Confederacy on August 12, 1861. On October 7, 1861, Ross signed a treaty with General Albert Pike of the Confederacy. The Cherokee officially joined other nations of the Five Civilized Tribes in supporting the Confederacy. After Union forces captured Ross on July 15, 1862, he sided with the Union and rejected the Confederate treaty. He stayed in Union territory until the war ended.

Stand Watie, a rival of Ross and a leader of the pro-Confederate Cherokee, became Principal Chief of the Southern Cherokee on August 21, 1862. Watie was a wealthy landowner and slaveholder. He served as an officer in the Confederate Army and was the last Confederate Brigadier General to surrender to the Union.

Cherokee people loyal to Ross supported the Union and recognized Ross as their Principal Chief. Pro-Confederate Cherokee sided with Watie. After the U.S. Emancipation Proclamation, the Cherokee National Council, led by acting Principal Chief Thomas Pegg, passed two laws that freed all enslaved African Americans in the Cherokee Nation.

The first law, "An Act Providing for the Abolition of Slavery in the Cherokee Nation," was passed on February 18, 1863. It stated that slavery caused problems and should be removed from the Cherokee Nation. The second law, "An Act Emancipating the Slaves in the Cherokee Nation," was passed on February 20, 1863. It declared all enslaved Black people in the Cherokee Nation to be free forever.

These laws became effective on June 25, 1863. Any Cherokee citizen who held slaves would be fined. Officials who did not enforce the act would be removed from office. The Cherokee became the only one of the Five Civilized Tribes to abolish slavery during the war. However, few slaves were actually freed. Those Cherokee loyal to the Confederacy owned more slaves than pro-Union Cherokee. Even though they agreed to end slavery, pro-Union Cherokee did not give Freedmen equal rights in the Cherokee Nation.

Fort Smith Conference and Treaty of 1866

After the Civil War ended in 1865, the Cherokee factions who supported the Union and those who supported the Confederacy were still in conflict. In September 1865, both sides met with delegations from the other Five Civilized Nations and other nations. They negotiated with the Southern Treaty Commission at Fort Smith, Arkansas. U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Dennis N. Cooley led the commission.

The Southern Cherokee delegates included Stand Watie. The Northern Cherokee, led by John Ross, were also there. U.S. officials treated the Cherokee as one group. They said that the Cherokee's rights, payments, and land claims from past treaties were no longer valid because the Cherokee had joined the Confederacy.

On September 9, Cooley insisted on several conditions for a treaty. These included ending slavery, giving full citizenship to the Cherokee Freedmen, and granting them rights to payments and land. The Southern Cherokee wanted their own independent nation. They also wanted the U.S. government to pay to move Freedmen out of the Cherokee Nation. The Pro-Union Cherokee, who had already abolished slavery, were willing to adopt Freedmen into the tribe and give them land.

The two factions continued negotiations in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Department of the Interior asked the new Freedmen's Bureau to watch how Freedmen were treated in Indian Territory. They also helped set up a free labor system.

The two Cherokee factions offered different treaty ideas to the U.S. government. Cooley gave each side twelve conditions. The Pro-Union Cherokee rejected four conditions but agreed to the rest. While the Southern Cherokee treaty had some support, the treaty offered by Ross's group was chosen. The Pro-Union faction was the only Cherokee group that the U.S. government made a treaty with. Issues like the status of Cherokee Freedmen and the Confederate treaty were already agreed upon. Both sides also compromised on issues like amnesty for Cherokee who fought for the Confederacy.

On July 19, 1866, six delegates representing the Cherokee Nation signed a Reconstruction treaty with the United States in Washington, D.C. This treaty gave Cherokee citizenship to the Freedmen and their descendants (article 9). The treaty also set aside a large area of land for Freedmen to settle. Each head of household would receive 160 acres (article 4). It also gave them voting rights and the right to govern themselves within the Cherokee Nation (article 5 and article 10).

Article 9 of The Treaty Of 1866 stated: "The Cherokee Nation having, voluntarily, in February, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, by an act of the national council, forever abolished slavery, hereby covenant and agree that never hereafter shall either slavery or involuntary servitude exist in their nation... They further agree that all freedmen who have been liberated... as well as all free colored persons who were in the country at the commencement of the rebellion, and are now residents therein, or who may return within six months, and their descendants, shall have all the rights of native Cherokees..."

Other nations of the Five Civilized Tribes also signed treaties in 1866. These treaties included articles about their Freedmen and ending slavery. The Chickasaw Nation was the only tribe that refused to include Freedmen as citizens. The Choctaw Nation later granted citizenship to Choctaw and Chickasaw Freedmen in 1885.

The Cherokee Nation Constitution was changed in a special meeting on November 26, 1866. The changes removed all language that excluded people of African descent. It repeated the treaty's language about the Freedmen. The constitution also repeated the treaty's six-month deadline for Freedmen to return to the Cherokee Nation to be counted as citizens. This meant Cherokee Freedmen could choose to live as citizens with the tribes or have U.S. citizenship outside the tribal nations.

The 1866 Amendments to Article 3, Section 5 of the 1836 Cherokee Nation Constitution stated: "All native born Cherokees, all Indians, and whites legally members of the Nation by adoption, and all freedmen who have been liberated... as well as free colored persons who were in the country at the commencement of the rebellion, and are now residents therein, or who may return within six months from the 19th day of July, 1866, and their descendants, who reside within the limits of the Cherokee Nation, shall be taken and deemed to be, citizens of the Cherokee Nation."

Becoming Part of the Nation and Facing Resistance

After the 1866 treaty was recognized, the Cherokee Nation tried to include the Freedmen. As citizens, Freedmen could vote in local and national elections. By 1875, Freedmen were elected to political office. The first Cherokee Freedman was elected to the Cherokee National Council.

During the 1870s, several separate schools for Freedmen were created. By 1872, seven primary schools were operating. A high school, Cherokee Colored High School, was built near Tahlequah in 1890. However, the Cherokee Nation usually did not fund these schools as well as those for Cherokee children.

Like the resistance of white people to accepting freedmen as citizens in the South, many Cherokee resisted including Freedmen as citizens. This issue became part of ongoing divisions within the tribe after the war. Some tribal members also did not want to share limited resources with their former slaves. There were also economic issues related to giving land to Freedmen, and later, dividing lands and distributing money from land sales.

Tribal Records and Rolls

1880 Census

In 1880, the Cherokee created a census to distribute money from the sale of the Cherokee Outlet. This was a piece of land west of the Cherokee Nation sold in the 1870s. The 1880 census did not include any Freedmen. It also left out the Delaware and Shawnee tribes, who had been adopted into the Cherokee Nation. In the same year, the Cherokee Senate voted to deny citizenship to Freedmen who applied after the six-month deadline from the 1866 treaty. Yet, some Freedmen who had never left the Nation were also denied citizenship.

The Cherokee claimed that the 1866 treaty gave civil and political rights to Freedmen, but not the right to share in tribal money. Principal Chief Dennis Wolf Bushyhead (1877–1887) disagreed with excluding Freedmen from money distribution. He believed their exclusion from the 1880 census broke the 1866 treaty. But his attempt to stop a law that added a "by blood" requirement for money distribution was overturned by the Cherokee National Council in 1883.

1888 Wallace Roll

In the 1880s, the U.S. government got involved to help the Cherokee Freedmen. In 1888, Congress passed a law to ensure Freedmen received their share of land money. It included $75,000 to make up for the tribe not paying them. Special Agent John W. Wallace was asked to investigate and create a list, now called the Wallace Roll, to help distribute federal money. The Wallace Roll, finished between 1889 and 1897, included 3,524 Freedmen.

The Cherokee Nation continued to challenge the rights of the Freedmen. In 1890, Congress allowed the U.S. Court of Claims to hear lawsuits by Freedmen against the Cherokee Nation to get back money they were denied. The Freedmen won this case, Whitmire v. Cherokee Nation and The United States (1912).

The Cherokee Nation appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Claims Court ruled that payments and other benefits could not be limited to a "particular class of Cherokee citizens, such as those by blood." The Supreme Court agreed, confirming the rights of Freedmen and their descendants to share in tribal money.

1894-1896 Kern-Clifton Roll

Since the Cherokee Nation had already distributed the money from the sale of the Cherokee Outlet, the U.S. government had to pay the Freedmen. The U.S. government created the Kern-Clifton roll in 1896. This list recorded 5,600 Freedmen who were to receive part of the land sale money. The payment process took ten years.

1898-1907 Dawes Rolls

Before the money was distributed, Congress passed the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887. This act aimed to make Native Americans in Indian Territory adopt American customs. It required ending tribal governments and land claims. Communal lands were to be given to individual families listed as tribal members. This was to encourage farming like European-Americans. Any remaining lands would be called "surplus" and sold to non-Native Americans. This led to huge land losses for the tribes.

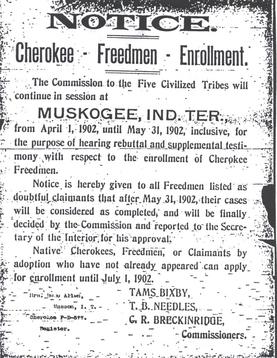

As part of this act, the Dawes Commission was formed in 1893. It took a census of citizens in Indian Territory from 1898 to 1906. The Dawes Rolls, officially called The Final Rolls of the Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory, listed people as Indians by blood, intermarried Whites, and Freedmen. The rolls were finished in March 1907. Even though Freedmen often had Cherokee ancestors, the Dawes commissioners usually listed all Freedmen or people with visible African features only on the Freedmen Roll. They did not record how much Cherokee ancestry a person had.

The process was not perfect. The Dawes Rolls of 1902 listed 41,798 citizens of the Cherokee Nation and 4,924 people listed separately as Freedmen. Intermarried white people were also listed separately. Overall, the Dawes Rolls are incomplete and not always accurate.

The 1898 Curtis Act also aimed to encourage assimilation. It allowed the Dawes Commission to distribute money without the tribal governments' approval. It also allowed the federal government to collect taxes from white citizens living in Indian territories. Native Americans saw both the Dawes and Curtis acts as limits on their right to govern themselves. The government distributed land, and there have been many claims of unfair treatment and mistakes in the registration process. For example, about 1,659 freedmen on the Kern-Clifton roll were not on the Dawes Rolls. This meant they lost their Cherokee citizenship rights. When the Cherokee Nation's government was officially ended and Oklahoma became a state (1907), the Cherokee Freedmen and other Cherokee became U.S. citizens.

Many activists have pointed out problems with the information in the Dawes Rolls. Some tribes have used these rolls to prove ancestry for membership. In earlier censuses, people of mixed African-Native American ancestry were often classified as Native American. The Dawes Commission created three categories: Cherokee by blood, intermarried White, and Freedmen. The people doing the registration usually did not ask individuals how they identified themselves.

In the later 1900s, the Cherokee and other Native Americans became more active in protecting their right to govern themselves. Being a citizen of a reorganized tribe became very important. In 1960, Gladys Lannagan, a member of the Cherokee Freedmen's Association, talked about problems with her family's records. She said she was born in 1896, but her father died before her name was added to the Dawes roll. She had two brothers on the roll, one as "by blood" and one as "Cherokee Freedman children's allottees." She said one of her grandparents was Cherokee and the other African American.

There have also been cases of mixed-race Cherokee people with African ancestry, who had as much as 1/4 Cherokee blood. But they were not listed as "Cherokee by blood" on the Dawes Roll. This was because they were only classified in the Cherokee Freedmen category. So, these individuals lost their "blood" claim to Cherokee citizenship even though they had a close Cherokee ancestor.

In 1924, Congress passed a law that allowed the Cherokee to sue the United States to get back the money paid to Freedmen in 1894-1896 under the Kern-Clifton Roll. This law said the Kern-Clifton Roll was only valid for that one distribution. It was replaced by the Dawes Rolls for establishing the Cherokee tribal membership list. With the Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946, Congress created a commission to hear Native American claims. Many descendants of the 1,659 Freedmen who were on the Kern-Clifton Roll but not the Dawes Roll organized to try to fix their ancestors' exclusion from Cherokee tribal rolls. They also sought payments they had been denied.

Loss of Membership Rights

On October 22, 1970, Congress gave the former Five Civilized Tribes the right to vote for their tribal leaders again. In 1971, the Department of the Interior said that one key condition for elections was that voter rules for the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole must include their Freedmen citizens. The Cherokee Nation, led by Principal Chief W.W. Keeler, gave voter cards to Freedmen. They participated in the first Cherokee elections since the 1900s and in later elections.

In the 1970s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs started providing federal services and benefits, like free healthcare, to members of federally recognized tribes. Many descendants of Cherokee listed as "Cherokee by blood" on the Dawes Commission Rolls joined the Cherokee Nation. As members, Cherokee Freedmen also received federal services. However, some benefits were limited. In 1974, Ross O. Swimmer, then-Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, said that Freedmen citizens should get certain health benefits like other enrolled Native Americans.

A new Cherokee Nation constitution was approved in 1975 and voted on by citizens in 1976. Article III, Section 1 of this new constitution defined citizens as those proven by the final Dawes Commission Rolls, including the adopted Delaware and Shawnee.

Efforts to block Freedmen descendants from the tribe began in 1983. Principal Chief Swimmer issued an order saying all Cherokee Nation citizens needed a CDIB card to vote. Before this, Cherokee Nation voter cards were used. CDIB cards were issued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs based on those listed as "Indians by blood" on the Dawes Commission Rolls. Since the Dawes Commission never recorded blood quantum for the Cherokee Freedmen Roll, Freedmen could not get CDIB cards.

Even though they were on the Dawes Rolls, received money from tribal land sales, and voted in previous elections, Cherokee Freedmen descendants were turned away from the polls. They were told they did not have the right to vote. According to Principal Chief Swimmer in a 1984 interview, new rules between 1977 and 1978 said that under the 1976 Cherokee Constitution, a person needed a CDIB card to enroll or vote. However, Article III of the 1976 constitution did not mention blood requirements for membership or voting.

Some people believed Swimmer's order was a way to exclude people who supported a rival candidate. After the 1983 elections and Swimmer's re-election, his rival, Perry Wheeler, filed lawsuits. Wheeler claimed the election broke federal and tribal law and that Cherokee Freedmen were unfairly removed from voting because they supported him. All these cases were unsuccessful.

Swimmer's successor, Wilma P. Mankiller, was elected in 1985. In 1988, the Cherokee Registration Committee approved new rules for tribal membership that were similar to Swimmer's voting requirements. On September 12, 1992, the Cherokee Nation Council passed a law requiring all enrolled members to have a CDIB card. Principal Chief Mankiller signed this law. From then on, Cherokee Nation citizenship was only given to people directly descended from an ancestor on the "Cherokee by blood" rolls of the Dawes Commission Rolls. This took away the voting rights of Cherokee Freedmen descendants.

Activism from the 1940s to 2000s

In the 1940s, over 100 descendants of freedmen formed the Cherokee Freedmen's Association. They filed a petition with the Indian Claims Commission in 1951 because they were excluded from citizenship. The petition was denied in 1961. The Indian Claims Commission said their claims were individual and outside the U.S. government's power.

The Cherokee Freedmen's Association faced two problems. First, the Dawes Rolls, a federal list, was accepted as defining who was legally Cherokee. Most of the Association members were not descended from people on the Dawes Rolls. Second, the courts saw their claims as a tribal matter, outside their power. Appeals continued until 1971, but all were denied.

On July 7, 1983, Reverend Roger H. Nero and four other Cherokee Freedmen were turned away from the polls. This was due to the new voting policy. Nero, who had voted in the 1979 election, and his colleagues complained to the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, claiming racial discrimination. On June 18, 1984, Nero and 16 Freedmen descendants filed a class action lawsuit against the Cherokee Nation. They sued Principal Chief Ross Swimmer, tribal officials, and U.S. government departments.

The lawsuit asked for nearly $750 million in damages and for the 1983 tribal election to be declared invalid. The court ruled against the Freedmen due to legal technicalities. The Court of Appeals made the same ruling in 1989. The courts said the case should have been filed in a claims court, not a district court, because of the large amount of money requested. No decision was made about the actual issues of the case.

Bernice Riggs, a Freedmen descendant, sued the Cherokee Nation's tribal registrar in 1998. This was because her citizenship application was denied. On August 15, 2001, the Judicial Appeals Tribunal (now the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court) ruled in the case of Riggs v. Ummerteskee. They said that while Riggs proved her Cherokee ancestry, she was denied citizenship because her ancestors on the Dawes Commission Rolls were only listed on the Freedmen Roll.

In September 2001, Marilyn Vann, another Freedmen descendant, was denied Cherokee Nation citizenship for the same reason. Even though she had documented Cherokee ancestry from earlier rolls, Vann's father was only listed as a Freedman on the Dawes Rolls. In 2002, Vann and other Freedmen descendants started the Descendants of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes organization. This group gained support from other Freedmen descendants, as well as Cherokee and non-Cherokee people. In 2005, the Delaware Tribe of Indians, one of the tribes that are Cherokee Nation members by treaty, supported the organization.

Recent Events (2004-2017)

Getting and Losing Citizenship Again

On September 26, 2004, Lucy Allen, a Freedmen descendant, filed a lawsuit with the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court. She argued that the laws blocking Freedmen descendants from tribal membership were against the constitution. On March 7, 2006, the Cherokee Nation Judicial Appeals Tribunal ruled in Allen's favor. They decided that the descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen were Cherokee citizens and could enroll. This was based on the fact that Freedmen were listed on the Dawes Rolls. Also, the 1975 Cherokee Constitution did not exclude them or require a blood requirement for membership. This ruling overturned the previous decision in Riggs v. Ummerteskee. More than 800 Freedmen descendants enrolled in the Cherokee Nation after this ruling.

Chad "Corntassel" Smith, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, said he was against the ruling. Smith called for a special meeting or vote to change the tribal constitution. He wanted to deny citizenship to Cherokee Freedmen descendants. On June 12, 2006, the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council voted to change the constitution. This change would limit Cherokee citizenship to descendants of people listed as "Cherokee by blood" on the Dawes Rolls. They rejected a vote on the issue.

Supporters of the special election, including former Cherokee Nation deputy chief John Ketcher, gathered signatures for a vote to remove the Freedmen descendants. Chief Smith announced that the issue of Freedmen membership would be voted on as part of proposed changes to the Cherokee Nation Constitution.

Freedmen descendants protested the election. Vicki Baker filed a complaint in the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court. She questioned the legality of the petition and claimed there was cheating. Although the Cherokee Supreme Court ruled against Baker, two justices, Darrell Dowty and Stacy Leeds, wrote separate opinions disagreeing with the ruling. Justice Leeds wrote that there were many problems and violations of Cherokee law in the petition drive. She also said some people who gathered signatures lied.

Despite the justices' disagreement and the removal of 800 signatures, the goal of 2,100 signatures was met.

Jon Velie, the attorney for the Freedmen descendants, asked the U.S. District Court to stop the election. Judge Henry H. Kennedy Jr. ruled against the Freedmen descendants' request. He said the election might not vote out the Freedmen. After some delays, the tribe voted on March 3, 2007. They voted on whether to change the constitution to exclude Cherokee Freedmen descendants from citizenship. Registered Cherokee Freedmen voters could participate. By a vote of 76% to 24%, the new rules excluded the Cherokee Freedmen descendants. The turnout was small compared to previous elections.

The Freedmen descendants protested their removal from the tribe. They held demonstrations at the BIA office in Oklahoma and at the Oklahoma state capitol. Because of the citizenship issues and the exclusion of Freedmen descendants, the Cherokee Nation was criticized by U.S. groups like the Congressional Black Caucus. On March 14, 2007, twenty-six members of the Congressional Black Caucus asked the Bureau of Indian Affairs to investigate the election.

Congressional Issues

On June 21, 2007, U.S. Representative Diane Watson introduced a bill, H.R. 2824. This bill aimed to remove the Cherokee Nation's federal recognition. It also sought to stop their federal funding (about $300 million annually) and their gaming operations. This would happen if the tribe did not honor the Treaty of 1866. The bill was supported by eleven other Congress members.

Chief Smith said that this bill was a "misguided attempt to deliberately harm the Cherokee Nation." The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) also disagreed with the bill.

On September 26, 2008, Congress passed the housing bill H.R. 2786. This bill included a rule that the Cherokee Nation could receive federal housing benefits. This was allowed as long as a tribal court order allowing citizenship for Cherokee Freedmen descendants was in place. Or, if some agreement was reached in the citizenship issue.

Federal Court Cases

Marilyn Vann and four Freedmen descendants filed a case with the United States Federal Court. They sued over the Cherokee Nation's removal of their voting rights. The Cherokee Nation tried to get the federal case dismissed.

On December 19, 2006, Federal Judge Henry Kennedy ruled that Freedmen descendants could sue the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Nation appealed, saying that as a sovereign nation, they were protected and could not be sued in U.S. court. On July 29, 2008, the Washington D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Cherokee Nation was protected. However, it said that the Cherokee Nation's officials were not protected. Freedmen descendants could sue the tribe's officers.

The ruling also stated that the 13th Amendment and the Treaty of 1866 limited the Cherokee's right to discriminate against Freedmen descendants. This meant the case would go back to district court. Velie said this was a big win for the Freedmen and Native American people. It meant they could take action against elected officials of their Native Nations and the United States.

In February 2009, the Cherokee Nation filed a separate federal lawsuit against individual Freedmen. This case was sent back to Washington to join the Vann case. Judge Terrance Kern transferred the Cherokee Nation v. Raymond Nash et al case to D.C. because it was similar to the Marilyn Vann et al v. Ken Salazar case. The first-to-file rule meant the Vann case needed to be heard first.

Since the Cherokee Nation filed the Cherokee Nation v. Nash case, they gave up their protection from lawsuits. This meant Judge Kennedy could now include the Cherokee Nation in the original case.

In October 2011, Judge Kennedy dismissed the Vann case for technical reasons. He sent the Nash case back to Federal District Court in Tulsa, OK. Velie said the Freedmen descendants would appeal the Vann dismissal.

Events in 2011

On January 14, 2011, Cherokee District Court Judge John Cripps ruled in favor of the Freedmen descendants. He reinstated their Cherokee Nation citizenship and enrollment. Cripps ruled that the 2007 constitutional amendment that removed Freedmen descendants was invalid. This was because it went against the Treaty of 1866, which guaranteed their rights as citizens.

The Cherokee Nation held elections for Principal Chief between Bill John Baker and Chad Smith on June 24, 2011. Baker was first declared the winner, then Smith, then Baker again after a recount. Smith appealed to the Cherokee Supreme Court, which said a clear winner could not be determined.

A special election was set for September 24, 2011. On August 21, 2011, before the special election, the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court reversed the January 14 decision. This resulted in the removal of Freedmen descendants from the rolls. Justice Darell Matlock Jr. ruled that the Cherokee people had the right to change their constitution and set citizenship rules. The decision was 4 to 1, with Justice Darrell Dowty disagreeing.

Many people questioned the timing of this decision. Freedmen voters, who voted in the June general election, were now unable to vote in the special election. The decision also removed the court order that had kept the Freedmen descendants in the Nation. On September 11, 2011, the Cherokee Nation sent letters to 2800 Freedmen descendants, telling them they were no longer citizens. In response, Jon Velie and the Freedmen descendants filed another request in federal district court to get their rights back for the election.

Because of the Cherokee Supreme Court ruling, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development stopped $33 million in funds for the Cherokee Nation. Larry Echo Hawk, Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, sent a letter to acting Principal Chief Joe Crittenden. He stated that the Department of the Interior never approved the Cherokee constitutional changes that excluded Freedmen descendants. Echo Hawk said the September 24, 2011 election would be considered unconstitutional if Freedmen descendants were excluded from voting. This was because the Treaty of 1866 guaranteed their rights.

On September 14, Cherokee Attorney General Diane Hammons suggested reopening the case. She recommended that the previous reinstatement be applied while arguments were scheduled. In a federal court hearing on September 20, 2011, Judge Henry Kennedy heard arguments. Afterward, the parties announced that the Cherokee Nation, Freedmen plaintiffs, and U.S. government had agreed. They would allow Freedmen descendants to be reinstated as citizens with the right to vote. Voting would continue for two additional days. The Cherokee Nation was to inform the Freedmen of their citizenship rights by September 22.

On September 23, 2011, Velie returned to court because almost none of the Freedmen descendants had received notification. The election was the next day. Judge Kennedy signed another order requiring more time for absentee ballots for Freedmen descendants and five days of walk-in voting for all Cherokee.

In October 2011, Bill John Baker became Principal Chief after the Cherokee Supreme Court rejected an appeal by former chief Chad Smith.

Motions, Developments, and Hearings (2012 to 2014)

The Cherokee Nation changed their lawsuit in May 2012. In response, on July 2, 2012, the U.S. Department of the Interior filed a counter-lawsuit against the Cherokee Nation. They wanted to stop the denial of tribal citizenship and other rights to the Freedmen. The Freedmen also filed lawsuits against certain Cherokee Nation Officers and the Cherokee Nation.

On October 18, 2012, the Vann case was heard by the United States District Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. On December 14, 2012, the court reversed the lower court's initial finding. It said that lawsuits for relief against government officials are allowed, even if the government itself has protection from lawsuits. This applies to Native American tribes as well. The case was sent back to the lower courts. In March 2013, the tribe's request to reconsider the decision was denied.

On September 13, 2013, the parties involved in the Vann and Nash cases, including the Cherokee, asked the United States District Court for the District of Columbia to decide if the Freedmen had equal citizenship rights under the Treaty of 1866. A hearing was held on May 5, 2014. After reviewing the request from the Department of the Interior, Judge Thomas F. Hogan said he doubted the treaty allowed the tribe to change its constitution to require "Indian blood" for Cherokee Nation citizenship. This hearing was the first in the 11-year controversy to look at the actual issues, not just legal procedures.

Citizenship Reinstated

On August 30, 2017, the U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the Freedmen descendants and the U.S. Department of the Interior. This was in the case of Cherokee Nation v. Raymond Nash et al. and Marilyn Vann et al.. The court ruled that according to Article 9 of the Cherokee Treaty of 1866, the Cherokee Freedmen descendants have current rights to citizenship that are the same as those of native Cherokees. Senior U.S. District Judge Thomas F. Hogan said that while the Cherokee Nation has the right to decide citizenship, it must do so fairly for both native Cherokees and the descendants of Cherokee Freedmen.

On August 31, Cherokee Nation Attorney General Todd Hembree stated that no appeal would be filed against the ruling. Since the ruling, citizenship applications from Freedmen descendants have been accepted and processed. Jon Velie, the lead lawyer for the Cherokee Freedmen, said the ruling was a victory for the Freedmen in getting their citizenship back. He also said it was a victory for Native Americans because federal courts enforced treaty rights while still respecting tribes' rights to determine citizenship and govern themselves.

Other Media About the Controversy

- By Blood (2015) is a documentary film. It was directed by Marcos Barbery and Sam Russell. The film is about the Cherokee Freedmen controversy and issues related to tribal self-governance. It has been shown at film festivals.

See also

- Black Indians in the United States

- Black Seminoles

- Chickasaw freedman

- Choctaw freedmen

- Creek freedmen

- Freedmen

- Post-civil rights era African-American history

- David Cornsilk

- Wilma Mankiller

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |