Black Indians in the United States facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| True population unknown, 269,421 identified as ethnically mixed with African and Native American on 2010 census | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (especially the Southern United States or in locations populated by Southern descendants), Oklahoma, New York and Massachusetts). | |

| Languages | |

| American English, Louisiana Creole, Gullah, Native American languages (including Navajo, Dakota, Cherokee, Choctaw, Mvskoke, Ojibwe), African languages |

|

| Related ethnic groups | |

Black Indians are Native American people who also have important African American family roots. They are considered Native American because they are connected to Native American communities and follow Native American cultures.

For a long time, some Native American tribes and African Americans had close relationships. This was especially true in places where slavery was common or where free people of color lived. Some members of the Five Civilized Tribes owned enslaved African Americans. Some enslaved or formerly enslaved people even moved with these tribes to the West during the Trail of Tears in 1830 and later during the period of Indian Removal.

More recently, some tribes like the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole have made their membership rules stricter. Sometimes, they have excluded "Freedmen" (descendants of formerly enslaved people) if those people did not have a Native American ancestor listed on the early 1900s Dawes Rolls. This decision has been challenged in courts. The Chickasaw Nation never gave citizenship to Chickasaw Freedmen.

Contents

Understanding Black Indians

For a long time, the history of how Native Americans and African Americans connected was not often studied in the United States. But these groups had many interactions. African people brought to the United States as slaves and their families shared cultures and sometimes married Native Americans. They also mixed with other people who had both Native American and European backgrounds.

Most of these interactions happened in New England early on, and in the Southern United States, where many people of African descent were enslaved. Today, many African Americans have some Native American ancestors. However, most of them did not grow up within Native American cultures and do not have strong social or cultural ties to Native peoples now.

The relationships between different Native Americans, Africans, and African Americans were varied and sometimes complicated. Some tribes welcomed ethnic Africans as full members of their communities. Other Native Americans used slavery themselves and did not oppose it for others. Some Native Americans and people of African descent fought together against the U.S. government, like in the Seminole Wars in Florida.

After the American Civil War, some African Americans joined the U.S. Army. Many were sent to fight against Native Americans in the Western frontier states. These military groups became known as the Buffalo Soldiers, a name given by Native Americans. Black Seminole men were especially hired from Indian Territory to work as scouts for the Army.

History of Connections

Early European Colonization

Records show that Africans and Native Americans first met in April 1502. This was when the first enslaved African arrived in Hispaniola. Some Africans escaped from the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo. Those who survived and joined local tribes became the first Black Indians. In the lands that later became the United States, the first recorded escape of an enslaved African to Native Americans happened in 1526.

In 1534, Pueblo peoples in the Southwest met an enslaved Moroccan man named Esteban de Dorantes. This was even before they met other Spanish explorers. Later, during the 1690 Pueblo Revolt, one of the leaders, Domingo Naranjo, was a Santa Clara Pueblo man with African ancestors.

In 1622, Algonquian Native Americans attacked the colony of Jamestown in Virginia. They killed most Europeans but took some enslaved Africans as captives. These Africans slowly became part of the Native American communities. Relationships between Africans (and later African Americans) and Native American tribes continued in the coastal states. Early on, colonists tried to enslave Native Americans, but they stopped this practice in the early 1700s.

Newspaper ads for runaway slaves often mentioned that Africans had connections with Native American communities. For example, some ads said slaves "ran off with his Indian wife" or "had kin among the Indians."

Several of the Thirteen Colonies made laws to stop slaves from going into Cherokee territory. This was to limit interactions between the two groups. Colonists even told the Cherokee that a smallpox outbreak in 1739 was caused by disease brought by African slaves. However, some tribes encouraged marriage with Africans, believing it would lead to stronger children.

Colonists in South Carolina were worried about mixed African and Native American populations. In 1725, they passed a law to stop taking slaves to frontier areas. In 1751, South Carolina made another law against keeping Africans near Native Americans. This was because planters thought it was bad for the colony's safety. Governor James Glen of South Carolina tried to make Native Americans dislike African Americans to prevent them from becoming allies.

In 1753, during Pontiac's War, someone in Detroit noticed that Native American tribes were killing white people but "saving and caressing all the Negroes they take." This person feared it could lead to a slave uprising. Similarly, Iroquois chief Joseph Brant welcomed runaway slaves and encouraged them to marry into his tribe. Native American adoption systems did not judge people based on color. Indian villages sometimes became stops on the Underground Railroad.

Historian Carter G. Woodson believed that Native American tribes offered a way for enslaved people to escape. Native American villages welcomed runaway slaves, and some served as stations on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War.

However, not all Native Americans felt the same way. In 1752, the "Catawaba tribe showed great anger and bitter resentment when an African American came among them as a trader."

European colonists tried to turn Native Americans and African Americans against each other. Europeans saw both groups as less important and tried to convince Native Americans that Africans were against their best interests.

In the colonial period, Native Americans received rewards if they returned escaped slaves. Later, in the late 1800s, African-American soldiers were assigned to fight in U.S. forces during the Indian Wars in the West.

European Enslavement Practices

Before Europeans arrived, some Native American groups held war captives. This was different from the European style of chattel slavery, where slaves were treated as property.

European colonists created a new demand for captives. Especially in the southern colonies, colonists bought or captured Native Americans to work on farms growing tobacco, rice, and indigo. To get trade goods like axes and rifles, Native Americans started selling war captives to white colonists instead of bringing them into their own societies. The English, Spanish, and Portuguese saw enslaving Africans and Native Americans as acceptable. They often said it was fair to enslave captives from a "just war" instead of killing them.

Native American slaves often escaped because they knew the land better than African slaves. So, Native Americans who were captured and sold were often sent to the West Indies or far from their homes.

The first known record of a permanent Native American slave was in Massachusetts in 1636. By 1661, slavery was legal in all thirteen colonies. Virginia later said "Indians, Mulattos, and Negros to be real estate." In 1682, New York stopped African or Native American slaves from leaving their master's property without permission. Europeans also viewed the enslavement of Native Americans differently in some ways. They believed Africans were "brutish," while Native Americans were sometimes seen as "noble" people who could become Christians.

It's thought that traders in Charles Town (South Carolina) sold about 30,000 to 51,000 Native American captives between 1670 and 1715. This was a profitable slave trade with the Caribbean and northern colonies. It was more profitable to have Native American slaves because African slaves had to be shipped and bought. Native slaves could be captured and taken directly to farms. White people in the Northern colonies sometimes preferred Native American slaves, especially women and children, because Native American women were good at farming, and children could be trained easily.

By the late 1700s, records showed slaves with both African and Native American heritage. In the eastern colonies, it became common to enslave Native American women and African men. This also led to many marriages between Africans and Native Americans. This practice was especially common in South Carolina.

Records from this time also show that many Native American women bought African men. But, without the European traders knowing, these women often freed the men and married them into their tribe. The Indian wars of the early 1700s, along with more African slaves becoming available, mostly ended the Native American slave trade by 1750. Many colonial slave traders were killed in the fighting. The remaining Native American groups joined together, determined to face Europeans from a position of strength.

Even though the Indian Slave Trade ended, the practice of enslaving Native Americans continued. Records from 1771 show Native American children were kept as slaves in Long Island, New York. Native Americans also married while enslaved, creating families with both Native and some African heritage. Newspapers from the later colonial period sometimes mentioned Native American slaves running away, being bought, or sold alongside Africans. Many former slaves also said they had a parent or grandparent who was Native American or partly Native American.

Advertisements asked for the return of both African American and Native American slaves. Records from the WPA (Works Progress Administration) show that Native Americans were still kidnapped and enslaved in the 1800s. These kidnappings showed that even then, little difference was made between African Americans and Native Americans.

During the time when Africans became the main group enslaved, Native Americans were sometimes enslaved at the same time. Africans and Native Americans worked together, lived together, and shared food recipes, herbal medicines, and stories. Some married and had mixed-race children. The exact number of Native Americans who were enslaved is not known. One estimate suggests between 147,000 and 340,000 Native Americans were enslaved in North America, not including Mexico.

Among the Cherokee, marriages between different races increased as the number of slaves held by the tribe grew. The Cherokee were known for having slaves work alongside their owners. The Cherokee's way of dealing with slavery was different from the European-American system of chattel slavery. This caused problems between them and European Americans. The Cherokee tribe started to become divided. As more white men married Native women and European culture was adopted, there was more discrimination against those with African-Cherokee blood and against African slaves.

After Native American slavery ended in the colonies, some African men chose Native American women as partners. This was because their children would be born free. Starting in 1662 in Virginia, a law called partus sequitur ventrem said that a child's status followed the mother's. Also, in many Native American tribes, children belonged to their mother's people, so they were raised as Native American. As Europeans expanded in the Southeast, African and Native American marriages became more common.

The 1800s and the Civil War

In the early 1800s, the U.S. government thought some tribes had disappeared, especially on the East Coast. There, Native Americans had lost most of their land. Few reservations existed, and Native Americans were seen as landless. At that time, the government did not have a separate category for Native Americans in their census. Those who stayed among European-American communities were often listed as "mulatto." This term was used for people of mixed Native American-white, Native American-African, and African-white heritage.

The Seminole people of Florida formed in the 1700s from Muscogee (Creek) and Florida tribes. They also included some Africans who had escaped slavery. Other maroons (runaway slave communities) formed separate groups near the Seminole and joined them in military actions. Many marriages happened between them. African Americans living near the Seminole were called Black Seminole. Hundreds of people of African descent moved with the Seminole when they were sent to Indian Territory. Others stayed with the few hundred Seminole who remained in Florida.

In contrast, an 1835 census of the Cherokee showed that 10% of their population had African ancestry. In those years, tribal censuses listed people of mixed Native American and African descent as "Native American." However, during the creation of the Dawes Rolls, which listed tribal members for land distribution, Cherokee Freedmen were usually listed separately. The people recording the rolls often judged by appearance and did not always ask if Freedmen had Cherokee ancestors, which would have put them on the "Cherokee by blood" rolls.

This issue has caused problems for their descendants today. The Cherokee Nation passed laws and changed their constitution to make membership more limited. Now, only those with proof of "Cherokee by blood" ancestry from the Dawes Rolls can be members. Western artist George Catlin described "Negro and North American Indian, mixed, of equal blood" as "the finest built and most powerful men I have ever yet seen." By 1922, a survey by John R. Swanton noted that half of the Cherokee Nation was made up of Freedmen and their descendants.

Former slaves and Native Americans also married in northern states. Massachusetts records before 1850 included notes of "Marriages of 'negroes' to Indians." By 1860, in some parts of the South, where race was often seen as just black or white, white lawmakers thought many Native Americans no longer counted as "Native American." This was because many were mixed and partly black. They did not understand that many mixed-race Native Americans identified as Indian by culture and family. Lawmakers wanted to take away Native American tax exemptions.

Freed African Americans, Black Indians, and Native Americans fought in the American Civil War against the Confederate Army. In November 1861, the Muscogee Creek and Black Indians, led by Creek Chief Opothleyahola, fought three battles against Confederate whites and their Native American allies. They wanted to reach Union lines in Kansas and offer their help. Some Black Indians served in "colored regiments" with other African-American soldiers.

Black Indians were part of regiments like the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry. Some Civil War battles happened in Indian Territory. The first battle there took place in July 1863, and Union forces included the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry.

Many Black Indians returned to Indian Territory after the Union won the Civil War. When the Confederacy and its Native American allies were defeated, the U.S. government required new peace treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes. These treaties required them to free their slaves and make those who chose to stay with the tribes full citizens of their nations. This meant they would have equal rights to money and land. These formerly enslaved people were called "Freedmen," such as Cherokee Freedmen, Chickasaw Freedmen, Choctaw Freedmen, Creek Freedmen, and Seminole Freedmen. The Cherokee government that supported the Union had freed their slaves in 1863, before the war ended. But the Cherokee who supported the Confederacy held their slaves until they were forced to free them.

Native American Slave Ownership

Slavery existed among Native Americans as a way to use war captives, even before Europeans arrived. This was different from the European style of chattel slavery, where slaves were treated as personal property. In Cherokee traditions, enslaving war captives was a temporary status. They could later be adopted into a family or released.

The U.S. Constitution and laws in some states allowed slavery after the American Revolution. So, Native Americans were legally allowed to own slaves, including those brought from Africa by Europeans. In the 1790s, Benjamin Hawkins, a federal agent for the southeastern tribes, encouraged them to own slaves. He said this would help them farm and run plantations like other Americans. The Cherokee tribe had more members who owned black slaves than any other Native American nation.

Records from the slavery period show some cases of harsh treatment of black slaves by Native Americans. However, most Native American masters did not use the worst practices of the Southern states. Federal Agent Hawkins thought the way the Southern tribes practiced slavery was not efficient because most did not practice chattel slavery. Travelers reported enslaved Africans were "in as good circumstances as their masters." A white Indian Agent, Douglas Cooper, was upset that Native Americans did not use harsher rules. He insisted that Native Americans invite white men to live in their villages and "control matters."

Even though less than 3% of Native Americans owned slaves, the idea of a racial class system and forced labor, along with pressure from European-American culture, caused problems in their villages. Some groups already had a class system based on "white blood." This was partly because mixed-race Native Americans sometimes had better connections with traders for goods. Among some groups, Native Americans with mixed white blood were at the top, pure Native Americans were next, and people of African descent were at the bottom. The higher status of partly white people might have come from the money and social connections passed on by their white relatives.

Members of Native groups owned many African-American slaves through the Civil War. Some of these slaves later shared their life stories for a WPA oral history project in the 1930s.

Native American Freedmen and Modern Challenges

After the Civil War, in 1866, the U.S. government required new treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes. These tribes had supported the Confederacy. The treaties required them to free their slaves and grant them citizenship and membership in their tribes. This was similar to how the United States freed slaves and granted them citizenship. These people were known as "Freedmen," like Muscogee or Cherokee Freedmen.

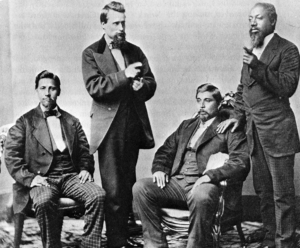

Similarly, the Cherokee had to let the Delaware rejoin their tribe. The Delaware had been given land on the Cherokee reservation earlier but fought for the Union during the war. Many Freedmen became active in their tribal nations for decades, working as interpreters and negotiators with the federal government. African Muscogee men, like Harry Island and Silas Jefferson, helped get land for their people when the government decided to give individual land plots to tribal members under the Dawes Act.

Some Maroon communities joined with the Seminole in Florida and intermarried. The Black Seminole group included people with and without Native American ancestry.

When the Cherokee Nation wrote its constitution in 1975, membership was limited to descendants of people listed on the Dawes "Cherokee By Blood" rolls. On the Dawes Rolls, U.S. government agents had classified people as Cherokee by blood, intermarried whites, and Cherokee Freedmen. This was done even if the Freedmen had Cherokee ancestry that would qualify them as "Cherokee by blood." The Shawnee and Delaware later gained their own federal recognition as the Delaware Tribe of Indians and the Shawnee Tribe. A political struggle over this issue has been going on since the 1970s. Cherokee Freedmen have taken their cases to the Cherokee Supreme Court. The Cherokee later gave the Delaware rights to be considered members of the Cherokee, but they opposed the Delaware's request for independent federal recognition.

The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruled in March 2006 that Cherokee Freedmen could join the tribe. In 2007, Cherokee Nation leaders held a special election to change their constitution. This change would make citizenship in the tribe more limited. The new rule, passed in March 2007, required direct Cherokee ancestry. This forced out Cherokee Freedmen and their descendants unless they also had documented "Cherokee by blood" ancestry. This has caused a lot of disagreement. The tribe decided to limit membership only to those who can prove Native American descent based on the Dawes Rolls.

Similarly, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma tried to exclude Seminole Freedmen from membership. In 1990, they received $56 million from the U.S. government as payment for lands taken in Florida. Because this money was based on tribal membership from 1823, it did not include Seminole Freedmen or Black Seminoles who owned land near Seminole communities. In 2000, the Seminole chief tried to formally exclude Black Seminoles unless they could prove descent from a Native American ancestor on the Dawes Rolls. About 2,000 Black Seminoles were excluded from the nation. Descendants of Freedmen and Black Seminoles are working to get their rights back.

There has never been any shame about intermarriage," says Stu Phillips, editor of The Seminole Producer, a local newspaper in central Oklahoma. "You've got Indians marrying whites, Indians marrying blacks. It was never a problem until they got some money.

A group that represents descendants of Freedmen from the Five Civilized Tribes says that their members should be citizens in both the Seminole and Cherokee nations. Many of them are indeed partly Native American by blood, with records to prove it. They say that because of racism, their ancestors were incorrectly listed only as Freedmen on the Dawes Rolls, even if they had Native American ancestry. Also, the group points out that after the Civil War, treaties with the U.S. government required these tribes to give African Americans full citizenship after they were freed, no matter their "blood quantum" (how much Native American ancestry they had). In many cases, it has been hard for people to trace their Native American ancestry through old records. Over 25,000 Freedmen descendants of the Five Civilized Tribes might be affected by these legal arguments.

The Dawes Commission enrollment records, which were meant to create lists of tribal members for land distribution, were made quickly by many different people. Many recorders tended to exclude Freedmen from Cherokee rolls and list them separately. This happened even when they said they had Cherokee ancestry, had records of it, and looked Cherokee. Descendants of Freedmen believe that the tribe's current use of the Dawes Rolls is a racist way to keep them from being citizens.

Before the Dawes Commission was created, most people with African blood living in the Cherokee nation before the Civil War were either slaves of Cherokee citizens or free black non-citizens. These free people were usually descendants of Cherokee men and women with African blood. In 1863, the Cherokee government made slavery illegal. In 1866, they signed a treaty with the U.S. government agreeing to give citizenship to people with African blood living in the Cherokee nations who were not already citizens. African Cherokee people were full citizens of that nation, holding office, voting, and running businesses.

After the Dawes Commission made tribal rolls, Freedmen of the Cherokee and the other Five Civilized Tribes were sometimes treated more unfairly. It became harder for them to be accepted into tribal structures in the following decades. Some tribes limited membership to those with a documented Native ancestor on the Dawes Commission lists. Many also limited who could hold office to those with direct Native American ancestry. Later in the 1900s, it was hard for Black Native Americans to officially connect with Native groups they were genetically related to. Many Freedmen descendants believe that their exclusion from tribal membership and the resistance to their efforts to gain recognition are based on racism. They think the tribes want to keep new gambling money for fewer people.

Family History and Genetics

African Americans trying to trace their family history can face many challenges. While some Native American nations have good historical records, the destruction of family ties and records during the Atlantic slave trade has made it much harder to track African American family lines. In his book Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, William Katz says the number of Black Indians among Native American nations was "understated by hundreds of thousands." He notes that pictures and stories show that when Black Indians were seen, white writers often did not mention or record them.

Enslaved Africans were renamed by their enslavers and usually did not have last names recorded until after the American Civil War. Historical records like censuses did not list the names of enslaved African Americans before the Civil War. While some large slave owners kept detailed records, which historians and family researchers have used, it is generally hard to trace African American families before the Civil War. Enslaved people were also forbidden from learning to read and write. They were punished harshly if they broke this rule, making family records kept by them very rare.

Older family members might have tried to keep an oral history of the family. But because of these many difficulties, these stories have not always been as accurate as hoped. Knowing where a family came from geographically can help people start piecing together their family history. By using oral history and existing records, descendants can try to confirm stories of African origins and any possible Native ancestry through family research and even DNA testing. However, DNA tests cannot perfectly show Native American ancestry, and no DNA test can tell you which specific tribe you are from.

DNA testing and research have provided some information about how much Native American ancestry African Americans have. This varies among people. Based on the work of geneticists, Harvard University historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr. hosted a popular TV series called African American Lives. In this series, geneticists said that DNA evidence shows Native American ancestry is much less common among African Americans than people used to think.

Their findings were that almost all African Americans have mixed racial backgrounds, and many have family stories of Native heritage. But usually, these stories turn out to be incorrect. Only about 5 percent of African American people show more than 2 percent Native American ancestry. Gates explained these numbers mean that "If you have 2 percent Native American ancestry, you had one such ancestor on your family tree five to nine generations back (150 to 270 years ago)." Their findings also showed that the most common "non-black" mix among African Americans is English and Scots-Irish. Some critics felt the TV series did not explain enough about the limits of DNA testing for heritage.

Another study, published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, also showed that despite how common these family stories are, relatively few African Americans with these stories actually had noticeable Native American ancestry. A study in the American Journal of Human Genetics stated, "We analyzed the European genetic contribution to 10 populations of African descent in the United States... mtDNA haplogroups analysis shows no evidence of a significant maternal Amerindian contribution to any of the 10 populations." Despite this, some people still believe that most African Americans have at least some Native American heritage. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. wrote in 2009:

Here are the facts: Only 5 percent of all black Americans have at least 12.5 percent Native American ancestry, which is like having at least one great-grandparent. Those 'high cheek bones' and 'straight black hair' your relatives brag about at every family reunion and holiday meal since you were 2 years old? Where did they come from? To paraphrase a well-known French saying, 'Seek the white man.'

African Americans, just like our first lady, are a racially mixed or mulatto people—deeply and overwhelmingly so. Fact: Fully 58 percent of African American people, according to geneticist Mark Shriver at Morehouse College, possess at least 12.5 percent European ancestry (again, the equivalent of that one great-grandparent).

Geneticists like Kim Tallbear (Dakota) and groups like The Indigenous Peoples Council on Biocolonialism (IPCB) agree that DNA testing is not how tribal identity is decided. Tallbear emphasizes that "People think there is a DNA test to prove you are Native American. There isn't." The IPCB notes that "Native American markers" are not found only among Native Americans. While they are more common among Native Americans, they are also found in people in other parts of the world. Tallbear also stresses that tribal identity is based on political citizenship, culture, family history, and family ties, not on "blood," "race," or genetics.

Writing for ScienceDaily, Troy Duster explained that the two common types of tests are Y-chromosome and mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) testing. These tests look at direct male and female ancestors. Each test only follows one line among many ancestors, so it might not find others. Although DNA testing for ancestry is limited, a paper in 2015 suggested that ancestry percentages can differ based on the region and gender of one's ancestors. These studies found that, on average, people who identified as African American in their sample group had 73.2-82.1% West African, 16.7%-29% European, and 0.8–2% Native American genetic ancestry. There was a lot of difference between individuals.

Autosomal DNA testing looks at DNA inherited from both parents. Autosomal tests focus on genetic markers that can be found in Africans, Asians, and people from all over the world. DNA testing still cannot determine a person's full ancestry with complete certainty.

Famous Black Native Americans

Claims of having both African American and Native American identity are sometimes debated. As Sharon P. Holland and Tiya Miles explain, old cultural ideas about race make this complicated. Blackness was often defined by the "one drop rule" (meaning if you had even one black ancestor, you were considered black). But "Indianness" was defined by the U.S. government using strict "blood quantum" rules. For example, the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 only recognized Native people with "one half or more Indian blood." It can sometimes be hard for Native people to show paper proof of their ancestry, especially for Black Natives, because their mixed-race ancestors might have been recorded only as black. Many tribes today still have blood quantum requirements for tribal membership.

The list below includes notable people with African American ancestry who are tribal citizens or have been recognized by their communities.

Historic Figures

- William Apess (African-Pequot, 1798–1839), a Methodist minister and writer.

- George Bonga (African-Ojibwe, 1802–1880), a fur trader and interpreter in what is now Minnesota.

- Billy Bowlegs III (African-Seminole, 1862–1965).

- Olivia Ward Bush (Montauk, 1869–1944), an author, poet, journalist, and tribal historian.

- Joseph Louis Cook (Mohawk tribal member of African-Abenaki descent, died 1814), a colonel in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.

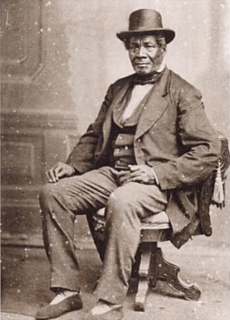

- Paul Cuffee (Ashanti/Wampanoag, 1759–1817).

- Pompey Factor (African-Seminole, 1849–1928), a Black Seminole Scout and Medal of Honor recipient.

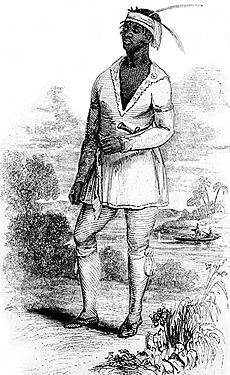

- John Horse, Juan Caballo (Black Seminole, 1812–1882), a war chief in Florida and leader of African-Seminole people in Mexico.

- Edmonia Lewis (African-Haitian-Mississauga, around 1845–1911), a sculptor.

- Adam Paine (African-Seminole, 1843–1877), a Black Seminole Scout and Medal of Honor recipient.

- Charlie Patton (African-Cherokee descent, 1887–1934), a founding father of the blues music in the Mississippi Delta.

- Isaac Payne (African-Seminole, 1854–1904), a Black Seminole Scout and Medal of Honor recipient.

- Marguerite Scypion (African-Natchez, around 1770s–after 1836), a freedwoman who won her freedom from slavery in court.

- John Ward (Medal of Honor) (African-Seminole, 1847 or 1848–1911), a Black Seminole Scout and Medal of Honor recipient.

Contemporary Figures

- Natalie Ball (Klamath/Modoc), born 1980, an artist who works in many different styles.

- Joe Burton (Soboba Luiseño), a basketball player.

- Radmilla Cody (Diné), 46th Miss Navajo Nation (1998), a traditional singer and enrolled member of the Navajo Nation with African-American ancestry. She was the first bi-racial Miss Navajo and speaks out against domestic violence.

- Angel Goodrich (Cherokee Nation), a WNBA basketball player for the Tulsa Shock and the Seattle Storm.

- Mary Ann Green (Augustine Cahuilla, 1964–2017), a chairperson who helped reestablish the Augustine Cahuilla reservation and tribal government.

- Lisa Holt (Cochiti Pueblo), a ceramic artist.

- Mwalim (Mashpee Wampanoag), a musician, writer, and educator.

- Harlan Reano (Kewa Pueblo), a ceramic artist.

- Angel Haze (Cherokee), born 1991, a Two-Spirit rapper and singer.

- Kyrie Irving (Lakota), born 1992, an NBA basketball player.

- France Winddance Twine (Muscogee (Creek) Nation, born 1960), a sociologist.

- William S. Yellow Robe Jr. (Assiniboine), a playwright and educator.

- Nyla Rose (Oneida descent), a professional wrestler, martial artist, and actress.

- Kelvin Sampson (Lumbee), a college basketball coach.

- Powtawche Valerino (Mississippi Choctaw), a NASA engineer.

- Delonte West (Piscataway), a retired NBA basketball player.

|

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |