Dawes Act facts for kids

|

|

| Other short titles | Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 |

|---|---|

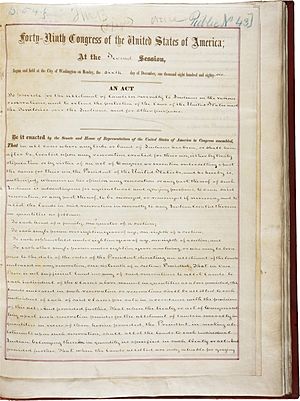

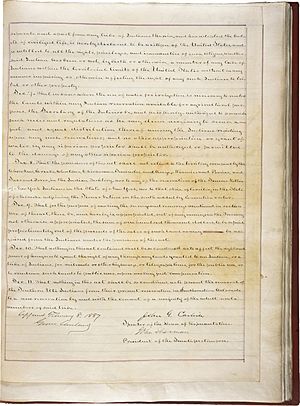

| Long title | An Act to provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and the Territories over the Indians, and for other purposes. |

| Nicknames | General Allotment Act of 1887 |

| Enacted by | the 49th United States Congress |

| Effective | February 8, 1887 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 49-105 |

| Statutes at Large | 24 Stat. 388 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 25 U.S.C.: Indians |

| U.S.C. sections created | 25 U.S.C. ch. 9 § 331 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

|

|

The Dawes Act of 1887 was a United States law that changed how land was owned by Native American tribes. It is also known as the General Allotment Act. This act was named after Senator Henry L. Dawes from Massachusetts.

Before this act, many Native American tribes owned land together. The Dawes Act allowed the U.S. President to divide this shared tribal land into smaller pieces. These pieces, called "allotments," were given to individual Native American families and people.

The main goal of the act was to change Native American land ownership from a shared system to a system of private property. This meant forcing Native Americans to think about land as something they could buy, sell, and own individually, which was different from their traditional ways. The act also allowed tribes to sell any leftover land to the U.S. government after the allotments were made.

The government also had to decide who was "Indian enough" to get land. This led to an official search for a definition of "Indian-ness." Even though the act passed in 1887, it was put into action for different tribes at different times. For example, the Hunter Act in 1895 applied the Dawes Act to the Southern Ute people.

The act aimed to protect Native American property. It also tried to make Native Americans fit into American society. Between 1887 and 1934, Native Americans lost about 100 million acres of land. This was about two-thirds of the land they had in 1887. This huge loss of land and the breaking up of tribal leadership caused many problems. Scholars now see the Dawes Act as one of the most harmful U.S. policies for Native Americans in history.

The "Five Civilized Tribes" (the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole) in Indian Territory were not part of the Dawes Act at first. The Dawes Commission was set up in 1893 to register tribal members for land allotments. This commission used "blood-quantum" (how much Native American ancestry someone had) to decide who belonged to a tribe.

However, it was hard to know exact bloodlines. So, the commission often called Native Americans who seemed less "Americanized" as "full-blood." Those who looked more like white people were called "mixed-blood," no matter their culture.

The Curtis Act of 1898 later made the Dawes Act apply to the "Five Civilized Tribes." This act ended their tribal governments and courts. It also divided their shared lands among individual tribal members. Any extra land was sold. This law helped prepare the land to become the state of Oklahoma. It also broke a promise that the Indian territory would always belong to Native Americans.

The Dawes Act was changed again in 1906 by the Burke Act.

During the Great Depression, the U.S. government passed the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934. This act stopped further land allotments. It also gave Native Americans new rights to organize and form their own governments. This helped them try to "rebuild an adequate land base."

Contents

Why the Dawes Act Was Created

The "Indian Problem" and Land Needs

In the early 1800s, the U.S. government faced what it called the "Indian Problem." Many new European immigrants were settling near Native American territories. These groups often clashed over land and resources. Many European Americans believed that Native Americans and white settlers could not live together in the same communities.

To solve this, William Medill, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, suggested creating "reservations." These would be areas just for Native Americans. This plan moved Native Americans from their homes to areas west of the Mississippi River. This allowed white settlers to take over lands in the Southeast, where there was a high demand for new farms.

This new policy aimed to keep Native Americans away from settlers. But it caused much suffering and many deaths. In the late 1800s, Native American tribes fought against the reservation system in what were called the Indian Wars. After many years, the tribes were defeated and agreed to move to reservations. Native Americans ended up with about 155 million acres of land. This land varied from dry deserts to good farming areas.

Life on Reservations and Calls for Change

Even though the reservation system was forced on Native Americans, it gave each tribe a claim to their new lands. It also offered some protection over their territories. Tribes also had the right to govern themselves. Native Americans tried to continue their traditions and ways of life.

However, the reservation system often had problems with corruption. Native Americans sometimes did not receive the supplies or money they were promised.

By the late 1880s, many people in the U.S. believed that Native Americans needed to become more like American culture. They thought this was important for their survival. This belief was held by those who admired Native Americans and those who wanted them to give up their tribal lands, traditions, and identities. Senator Henry Dawes led a movement to end tribal ownership of land. He wanted to give individual land pieces to Native American families.

Goals of the Dawes Act

On February 8, 1887, President Grover Cleveland signed the Dawes Allotment Act into law. This act divided tribal reservations into plots of land for individual households. Reformers hoped the Dawes Act would achieve six main goals:

- Break up tribes as a social unit.

- Encourage individuals to work for themselves.

- Help Native American farmers improve.

- Reduce the cost of managing Native American affairs.

- Keep some parts of the reservations as Native American land.

- Open the rest of the land to white settlers for profit.

The act aimed to make Native Americans more "Euro-Americanized." The government divided the reservations, hoping Native Americans would become farmers. Native Americans traditionally valued land as something to be cared for. It was part of their identity and supported life. They did not see land mainly for economic profit, unlike most white settlers.

However, many Native Americans began to feel they had to change to survive. They felt they needed to adopt the values of the main society. This meant seeing land as property to be bought and sold. They were expected to become successful farmers. As they became U.S. citizens, they were expected to give up their traditional ways. They were to become self-supporting citizens who no longer needed government help.

What the Dawes Act Said

The Dawes Act had several important rules:

- A family head would get 160 acres of land.

- A single person or orphan over 18 would get 80 acres.

- People under 18 would get 40 acres each.

- The U.S. Government would hold these allotments "in trust" for 25 years. This meant the government managed the land, and it could not be sold during this time.

- Eligible Native Americans had four years to choose their land. If they didn't, the Secretary of the Interior would choose for them.

Every Native American who received land was subject to the laws of the state or territory where they lived. If a Native American received land and "adopted the habits of civilized life" (lived separately from the tribe), they also became a U.S. citizen. This citizenship did not affect their right to tribal property.

The Secretary of the Interior could also make rules to ensure fair water distribution for farming among tribes.

The Dawes Act did not apply to certain territories at first:

- The Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Miami, and Peoria in Indian Territory.

- The Osage and Sac and Fox in the Oklahoma Territory.

- Any reservations of the Seneca Nation of New York.

- A strip of land in Nebraska next to the Sioux Nation.

- The Red Lake Ojibwe Reservation.

- The Osage Tribe of Oklahoma.

Later, the act's rules were extended to the Wea, Peoria, Kaskaskia, Piankeshaw, and Western Miami tribes in 1889. The division of lands for these tribes was made mandatory by an Act in 1891, which added to the Dawes Act.

Changes to the Dawes Act

1891 Amendments

In 1891, the Dawes Act was changed:

- It allowed for fair land distribution if a reservation did not have enough land for everyone to get the original amounts. If land was only good for grazing, double the amount could be given.

- It set rules for how land could be inherited.

- It did not apply to the Cherokee Outlet.

Curtis Act of 1898

The Curtis Act of 1898 made the Dawes Act apply to the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory. It ended their self-government, including tribal courts. It also allowed the Dawes Commission to decide who was a tribal member when registering people for land.

Burke Act of 1906

The Burke Act of 1906 changed parts of the Dawes Act. It dealt with U.S. Citizenship and how allotments were given out. The Secretary of Interior could force a Native American land owner to accept full ownership of their land. U.S. Citizenship was given automatically when someone received their land allotment. The land given to Native Americans was no longer held in trust and became subject to taxes. The Burke Act did not apply to any Native Americans in Indian Territory.

Impacts of the Dawes Act

Identity and Loss of Tribal Connection

The Dawes Act had a damaging impact on Native American self-rule, culture, and identity. It allowed the U.S. government to:

- Decide who was "Indian" by law.

- Use the idea of "blood-quantum" (how much Native American ancestry) to define Native Americans.

- Create divisions between "full-bloods" and "mixed-bloods."

- Remove many Native Americans from their tribal connections.

- Take large amounts of Native American land legally.

The government saw the Dawes Act as a successful "democratic experiment." They continued to use blood-quantum laws and "federal recognition" to decide who received services like healthcare and education. Under the Dawes Act, land was given based on perceived blood quanta. Those called "full-blooded" received smaller land pieces. The government kept control of these lands for at least 25 years. Those called "mixed-blood" received larger, better lands with full control. But they were also forced to become U.S. citizens and give up their tribal status.

Also, Native Americans who did not fit the "full-blood" or "mixed-blood" rules lost their Native American identity. They were removed from their homelands. While the Dawes Act is often seen as the main cause of divisions between tribal and non-tribal Native Americans, this process of losing tribal connection actually started before the Dawes Act.

Land Loss

The Dawes Act ended the Native American tradition of owning property together. This shared ownership had ensured that everyone had a home and a place in the tribe. The act aimed to destroy tribes and their governments. It also opened Native American lands to white settlers and railroads.

Land owned by Native Americans dropped from about 138 million acres in 1887 to 48 million acres in 1934.

Senator Henry M. Teller of Colorado was against the allotment policy. In 1881, he said it was a policy "to rob the Indians of their lands." He also said that the real goal was to get Native American lands for settlement. He believed it was worse to do this in the name of "Humanity" than just for "Greed."

In 1890, Dawes himself noted that Native Americans were losing their land to settlers. He said, "I never knew a white man to get his foot on an Indian's land who ever took it off." The amount of land held by Native Americans quickly fell from about 150 million acres to 78 million acres by 1900. The remaining land, after allotments, was declared "surplus" and sold to non-Native settlers, railroads, and other companies. Other parts became federal parks or military bases. The focus shifted from helping Native Americans own land to meeting the demand of white settlers for more land.

The land given to most Native Americans was not enough for successful farming. When allottees died, their land was divided among their heirs. This quickly led to very small, shared land pieces. Most allotted land could be sold after 25 years. It was often sold to non-Native buyers at low prices. Also, land considered "surplus" was opened to white settlers. Profits from these sales were often supposed to help Native Americans. Over 47 years, Native Americans lost about 90 million acres of treaty land. This was about two-thirds of their land base in 1887. About 90,000 Native Americans became landless.

Culture and Gender Roles

The Dawes Act forced Native Americans to adopt European American culture. It made Indigenous cultural practices illegal. It also pushed settler cultural ideas onto Native American families and children. By changing shared Native land into private property, the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) hoped to turn Native Americans into farmers. They wanted Native American men to be farmers and women to be farm wives.

To do this, the Dawes Act "outlawed Native American culture." It created a "code of Indian offenses" that regulated behavior based on European American rules. Violations were tried in a "Court of Indian Offenses" on each reservation. The Dawes Act also included money to teach Native Americans European American ways of thinking and behaving through Indian Service schools.

The legal taking of Native American lands changed their home life, gender roles, and tribal identity. For example, a key goal of the Dawes Act was to change Native American gender roles. White settlers in the late 1800s thought women's work in Native societies was less important than men's. They saw it as a sign of women's "disempowerment." They thought women doing tasks like farming or building homes was wrong. In reality, these tasks gave many Indigenous women respect and status within their tribes.

By dividing reservation lands into privately owned pieces, lawmakers hoped to complete the assimilation process. They wanted to force Native Americans to have individual households. They also wanted to strengthen the nuclear family and focus on economic dependence within this small family unit. The Dawes Act aimed to destroy "native cultural patterns." It did this by changing the environment to cause social change. Private property ownership was the main idea of the act. But reformers believed that civilization also needed changes to social life in Indigenous communities. So, they promoted Christian marriages among Indigenous people. They forced families to reorganize under male heads. They also trained men for jobs that earned wages. Women were encouraged to support them at home through domestic activities.

Loss of Self-Rule

In 1906, the Burke Act changed the Dawes Act. It gave the Secretary of the Interior the power to give full ownership of land to Native Americans judged "competent and capable." The rules for this judgment were unclear. But it meant that if the Secretary of the Interior thought a Native American was "competent," their land would no longer be held in trust. It would then be taxed and could be sold by the owner. If Native Americans were judged "incompetent," the federal government automatically leased out their land.

The act stated: "... the Secretary of the Interior may, in his discretion, and he is hereby authorized, whenever he shall be satisfied that any Native American allottee is competent and capable of managing his or her affairs at any time to cause to be issued to such allottee a patent in fee simple, and thereafter all restrictions as to sale, encumbrance, or taxation of said land shall be removed."

The idea of "competence" made the decision very subjective. This increased the power of the Secretary of Interior to exclude people. Even though this act gave owners the choice to keep or sell their land, the difficult economic times meant that selling Native American lands was almost certain. The Department of Interior knew that almost 95% of fully owned land would eventually be sold to white people.

In 1926, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work asked for a study of federal Native American policy. The study, finished in 1928, was called The Problem of Indian Administration. It is known as the Meriam Report after its director, Lewis Meriam. This report showed fraud and misuse of funds by government agents. It specifically found that the General Allotment Act had been used to illegally take Native American land rights.

After much discussion, Congress ended the allotment process of the Dawes Act. This happened with the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. However, the allotment process in Alaska continued until 1971.

Even though the allotment process ended in 1934, the effects of the General Allotment Act continue today. For example, the act created a trust fund. This fund was managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. It collected and distributed money from oil, mineral, timber, and grazing leases on Native American lands. The BIA's poor management of this fund led to lawsuits. One major case, Cobell v. Kempthorne, was settled in 2009 for $3.4 billion. This lawsuit aimed to force a proper accounting of the money.

Fractionation: Dividing Land into Tiny Pieces

For almost a hundred years, a problem called fractionation has grown from the federal Indian allotments. When original land owners die, their heirs receive equal, undivided shares of the land. In later generations, these shares become even smaller. These tiny, shared interests in individual Native American land keep growing with each new generation.

Today, there are about four million owners for 10 million acres of individually owned trust lands. This makes managing these trust assets very difficult and costly. These four million interests could grow to 11 million by 2030. Some single pieces of property have ownership interests that are less than one-millionth of the whole. This tiny share might be worth less than a penny.

The economic problems caused by fractionation are serious. Studies suggest that when a piece of land has between ten and twenty owners, its value drops to zero. Land that is highly fractionated is almost worthless.

Also, the division of land and the huge number of trust accounts created a management nightmare. Over the past 40 years, the amount of trust land has grown by about 80,000 acres per year. About $357 million is collected each year from managing trust assets. This includes money from coal sales, timber, oil and gas leases, and other activities. No single financial institution has ever managed as many trust accounts as the Department of the Interior has.

The Interior Department manages 100,000 leases for individual Native Americans and tribes on about 56 million acres of trust land. About $226 million per year is collected from leases, permits, and sales for about 230,000 individual Native American money accounts. About $530 million per year is collected for about 1,400 tribal accounts. The trust also manages about $2.8 billion in tribal funds and $400 million in individual Native American funds.

Under current rules, a legal process (probate) is needed for every account with trust assets. This is true even for accounts with balances between one cent and one dollar. The average cost for a probate process is over $3,000. Even a faster process costing $500 would need almost $10,000,000 to handle the $5,700 in these small accounts.

Unlike most private trusts, the federal government pays all the costs of managing the Indian trust. So, there is no reason to reduce the number of small or inactive accounts. The U.S. also has not used tools that states use to ensure unclaimed property is put to good use.

Fractionation is not a new problem. In the 1920s, the Brookings Institution studied the conditions of Native Americans. This study, the Meriam Report (1928), included information on the effects of fractionation. Its findings helped create land reform ideas for the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). The original IRA included plans for probate and land consolidation. But because of opposition, most of these plans were removed. The final IRA only had a few basic land reform and probate measures. While Congress made big changes for tribes through the IRA and stopped allotments, it did not fully solve the problem of fractionation.

In 1922, the General Accounting Office (GAO) checked 12 reservations to see how bad fractionation was. The GAO found that on these 12 reservations, there were about 80,000 different owners. But because of fractionation, there were over a million ownership records for those owners. The GAO also found that if the land were physically divided by the small shares, many interests would be less than one square foot. In early 2002, the Department of the Interior tried to repeat this study. They found that fractionation increased by over 40% between 1992 and 2002.

Here is an example of ongoing fractionation from a real piece of land in 1987: A 40-acre piece of land made $1,080 a year. It was worth $8,000. It had 439 owners. One-third of them received less than $.05 a year in rent. Two-thirds received less than $1. The largest owner received $82.85 a year. The smallest heir received $.01 every 177 years. If the land was sold for $8,000, that heir would get $.000418. The cost to manage this land was $17,560 a year.

Today, this same land makes $2,000 a year and is worth $22,000. It now has 505 owners. If the land was sold for $22,000, the smallest heir would get $.00001824. The cost to manage this land in 2003 was $42,800.

Fractionation has become much worse. In some cases, the land is so divided that it can never be used productively. With such tiny ownership shares, it is almost impossible to get enough owners to agree to lease the land. Also, to manage highly fractionated lands, the government spends more money on legal processes, record keeping, leasing, and distributing tiny amounts of money than it receives from the land. Often, the costs of managing these lands are much more than the land's actual value.

Criticisms of the Act

Angie Debo's book, And Still the Waters Run: The Betrayal of the Five Civilized Tribes (1940), argued that the Dawes Act's allotment policy was used to unfairly take land and resources from Native Americans. This was especially true for the Five Civilized Tribes through the Dawes Commission and the Curtis Act of 1898. Ellen Fitzpatrick said Debo's book showed "the corruption, moral decay, and criminal activity" behind how white officials managed the allotment policy.

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |