Grover Cleveland facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Grover Cleveland

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 22nd & 24th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1893 – March 4, 1897 |

|

| Vice President | Adlai Stevenson I |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Harrison |

| Succeeded by | William McKinley |

| In office March 4, 1885 – March 4, 1889 |

|

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Chester A. Arthur |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Harrison |

| 28th Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1883 – January 6, 1885 |

|

| Lieutenant | David B. Hill |

| Preceded by | Alonzo B. Cornell |

| Succeeded by | David B. Hill |

| 35th Mayor of Buffalo | |

| In office January 2, 1882 – November 20, 1882 |

|

| Preceded by | Alexander Brush |

| Succeeded by | Marcus M. Drake |

| 17th Sheriff of Erie County | |

| In office January 1, 1871 – December 31, 1873 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles Darcy |

| Succeeded by | John B. Weber |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Stephen Grover Cleveland

March 18, 1837 Caldwell, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | June 24, 1908 (aged 71) Princeton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Resting place | Princeton Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 6, including Ruth, Esther, Richard, and Francis |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

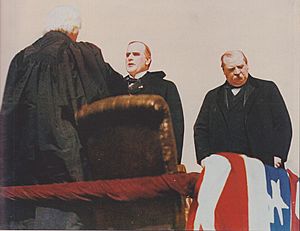

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908) was an American politician. He served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States. His terms were from 1885 to 1889 and again from 1893 to 1897. He is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms.

Cleveland was known for being honest and fighting against corruption. He won the most votes from people in three presidential elections: 1884, 1888, and 1892. However, Benjamin Harrison won the presidency in 1888 by getting more electoral college votes.

Cleveland was one of only two Democrats to be president between 1861 and 1933. This was a time when Republicans usually won the presidency.

Some people criticized Cleveland for not being imaginative. They felt he struggled with the nation's economic problems, like depressions and strikes, during his second term. By the end of his second term, he was not very popular, even among people in his own party. After leaving the White House, Cleveland retired to his home in Princeton, New Jersey. He continued to share his political opinions until he became very ill in 1907. He died in 1908 at age 71.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born on March 18, 1837, in Caldwell, New Jersey. His parents were Ann (née Neal) and Richard Falley Cleveland. His father was a minister from Connecticut. His mother was from Baltimore.

Grover was the fifth of nine children. In 1841, his family moved to Fayetteville, New York. He spent most of his childhood there. Neighbors said he was "full of fun and inclined to play pranks." He also loved outdoor sports.

Cleveland went to Fayetteville Academy and Clinton Liberal Academy for his early schooling. When his father died in 1853, he left school to help his family. Later that year, his brother William got him a job as an assistant teacher. This was at the New York Institute for the Blind in New York City.

Cleveland returned home in 1854. An elder in his church offered to pay for his college if he promised to become a minister. Cleveland said no. In 1855, he decided to move west.

Starting His Career

Cleveland first stopped in Buffalo, New York. His uncle-in-law, Lewis F. Allen, gave him a job as a clerk. Allen was an important person in Buffalo. He introduced Cleveland to powerful men, including lawyers at Rogers, Bowen, and Rogers. Cleveland later worked as a clerk for this firm. He studied law with them and became a lawyer in New York in 1859.

Cleveland worked for the Rogers firm for three years. In 1862, he started his own law practice. In January 1863, he became an assistant district attorney for Erie County.

As a lawyer, Cleveland was known for being very focused and hardworking. He lived simply and used his earnings to support his mother and younger sisters.

Political Journey

Cleveland joined the Democratic Party early in his career. In 1870, he became the sheriff of Erie County, New York. This job paid well. After his term as sheriff, Cleveland went back to practicing law. He started a firm with his friends Lyman K. Bass and Wilson S. Bissell.

In 1881, Cleveland was elected mayor of Buffalo. Then, in 1882, he became governor of New York. He fought against political corruption. This made him popular. Many Republicans who also disliked corruption, called "Mugwumps", supported him in the 1884 election.

First Time as President (1885–1889)

When Cleveland became president, he had to fill many government jobs. These jobs were often given to political supporters, known as the spoils system. But Cleveland said he would not fire Republicans who were doing a good job. He also said he would not hire people just because they were in his party. He tried to reduce the number of government workers. Many departments had too many people hired for political reasons. Cleveland tried to hire people based on their skills, more than past presidents.

Cleveland also made other government changes. In 1887, he signed a law that created the Interstate Commerce Commission. This group helped regulate railroads. He and his Secretary of the Navy, William C. Whitney, worked to make the navy more modern. They canceled contracts for ships that were not built well.

Cleveland also upset railroad companies. He ordered an investigation into lands they held from the government. The Secretary of the Interior said these lands should be returned to the public. This was because the railroads did not build their lines as they had agreed. About 81 million acres (330,000 km²) of land were returned.

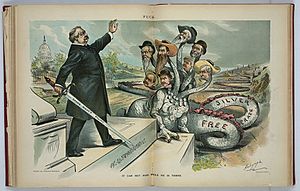

Cleveland did not like high tariffs (taxes on imported goods). He also opposed "free silver" (a policy to increase the amount of money in circulation). He was against imperialism and giving government money to businesses, farmers, or veterans.

Cleveland focused on making the military strong for self-defense. In 1885, he created a board to suggest new coastal defenses for the U.S. Most of their ideas were put into action. By 1910, 27 places were protected by over 70 forts.

Cleveland, like many Northerners and most white Southerners, thought Reconstruction had failed. He was careful about using federal power to enforce the 15th Amendment. This amendment gave African Americans the right to vote. Cleveland did not appoint black Americans to many jobs. However, he allowed Frederick Douglass to keep his job in Washington, D.C. When Douglass resigned, Cleveland appointed another black man to replace him.

Cleveland believed that Chinese immigrants would not fit into white society. His Secretary of State worked to extend the Chinese Exclusion Act. Cleveland also pushed Congress to pass the Scott Act. This law stopped Chinese immigrants who left the U.S. from returning. Cleveland signed the Scott Act into law on October 1, 1888.

Cleveland saw Native Americans as needing government protection. He said the government should work to improve their lives and protect their rights. He supported the idea of Native Americans adopting white culture. He pushed for the Dawes Act. This law divided Native American lands among individual tribal members. Before, the land was held by the federal government for the tribes. Some Native leaders supported the act, but most Native Americans did not like it. Cleveland thought the Dawes Act would help Native Americans escape poverty and join white society. However, it often weakened tribal governments and allowed individuals to sell their land.

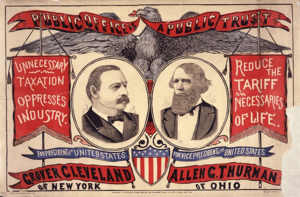

1888 Election and Time Away from Office (1889–1893)

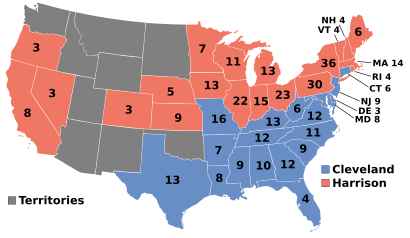

In 1888, the Republicans chose Benjamin Harrison for president. Cleveland was nominated again by the Democrats. The election focused on key states like New York and Indiana. In 1884, Cleveland had won these states. But in 1888, he lost his home state of New York.

Cleveland won more individual votes across the country than Harrison. However, Harrison won more electoral college votes (233 to 168). This meant Harrison became president.

As Frances Cleveland left the White House, she told a staff member, "I want you to take good care of all the furniture... for I want to find everything just as it is now, when we come back again." When asked when she would return, she said, "We are coming back four years from today."

The Clevelands moved to New York City. Cleveland worked at a law firm. He spent a lot of time at their vacation home, Gray Gables, where he loved to fish. While in New York, their first child, Ruth, was born in 1891.

Second Time as President (1893–1897)

Soon after Cleveland's second term began, the Panic of 1893 hit the stock market. This led to a serious economic depression. Cleveland had already changed the silver policy from the Harrison administration. Next, he wanted to change the effects of the McKinley Tariff.

The Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act passed the House of Representatives easily. This bill suggested lowering tariffs, especially on raw materials. To make up for lost money, it included an income tax of two percent on incomes over $4,000.

The bill then went to the Senate. There, it faced strong opposition. The Senate added over 600 changes that removed most of the original reforms. Cleveland was very angry with the final bill. Still, he thought it was better than the McKinley tariff. So, he allowed it to become law without his signature.

Cleveland's second administration also worked to modernize the military. They ordered the first ships for a navy that could attack, not just defend. Construction continued on coastal forts started during his first term. These new ships nearly doubled the Navy's battleships.

The Panic of 1893 made working conditions worse across the U.S. Anti-silver laws also made workers in the West unhappy. A group of workers led by Jacob S. Coxey began marching toward Washington, D.C. They were protesting Cleveland's policies. This group, called Coxey's Army, wanted a national roads program to create jobs. They also wanted weaker currency to help farmers pay debts. Only a few hundred people remained when they reached Washington. They were arrested for walking on the lawn of the United States Capitol. The group then broke up. Even though Coxey's Army was not a big threat, it showed growing unhappiness in the West with money policies from the East.

Cleveland also got involved in the 1894 Pullman Strike. He acted to keep the railroads running. This angered both Illinois Democrats and labor unions across the country.

Foreign Policy (1893–1897)

When Cleveland took office again, he faced the issue of Hawaii. In his first term, he had supported trade with the Hawaiian Kingdom. He also accepted a deal that gave the U.S. a naval station in Pearl Harbor.

However, in 1893, businessmen in Honolulu, many of European and American background, overthrew Queen Liliuokalani. They set up a temporary government and wanted Hawaii to join the United States. The Harrison administration had quickly agreed to a treaty to annex Hawaii. But U.S. Marines were present in Honolulu when the overthrow happened. This caused a lot of debate.

Five days after becoming president, Cleveland withdrew the treaty from the Senate. He sent a former Congressman, James Henderson Blount, to Hawaii to investigate. Cleveland agreed with Blount's report. It found that Native Hawaiians did not want to be annexed. It also found that the U.S. had been involved in the overthrow.

Cleveland was against imperialism. He opposed the U.S. actions in Hawaii and wanted the queen to be restored. He did not approve of the new temporary government. By December 1893, the issue was still not solved. Cleveland sent a message to Congress, rejecting annexation. He encouraged Congress to continue the American tradition of not interfering in other countries. Later, Cleveland stopped pushing to restore the queen. He recognized and kept diplomatic relations with the new Republic of Hawaii.

Closer to home, Cleveland used a broad interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. This policy not only stopped new European colonies in the Americas. It also said that the U.S. had an interest in any important matter in the Western Hemisphere.

Life After the Presidency (1897–1908)

After leaving the White House on March 4, 1897, Cleveland lived in retirement. He moved to his estate, Westland Mansion, in Princeton, New Jersey. For a time, he was a trustee of Princeton University. He often consulted with President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909).

Cleveland continued to share his political views. In a 1905 article, he wrote about the women's suffrage movement. He stated that "sensible and responsible women do not want to vote."

Death

Cleveland's health had been getting worse for several years. In the fall of 1907, he became very ill. In 1908, he had a heart attack. He died on June 24 at age 71 in his Princeton home. His last words were, "I have tried so hard to do right." He is buried in the Princeton Cemetery.

Marriage and Family

Cleveland was 47 years old when he became president. He was a bachelor. His sister Rose Cleveland joined him and served as the White House hostess for his first two years.

Cleveland did not stay a bachelor for long. In 1885, the daughter of Cleveland's friend Oscar Folsom visited him in Washington. Her name was Frances Folsom. She was a college student. When she returned to school, President Cleveland got her mother's permission to write to her. Soon, they were engaged to be married.

Their wedding took place on June 2, 1886. It was held in the Blue Room at the White House. Cleveland was 49 years old; Frances was 21. He was the second president to marry while in office. He is still the only president to marry inside the White House.

The Clevelands had five children: Ruth (1891–1904), Esther (1893–1980), Marion (1895–1977), Richard (1897–1974), and Francis (1903–1995). Their granddaughter was the British philosopher Philippa Foot. Ruth became sick in 1904 and died five days later. The Curtiss Candy Company later said the "Baby Ruth" candy bar was named after her.

Honors and Memorials

During his first term, Cleveland looked for a summer home near Washington, D.C. He secretly bought a farmhouse in 1886. He remodeled it into a Queen Anne style summer estate. He sold it after losing the 1888 election. Later, this area became known as Cleveland Heights, then Cleveland Park.

Grover Cleveland Hall at Buffalo State College is named after him. Cleveland was on the first board of directors for the school. Grover Cleveland Middle School in his birthplace is named for him. So is Grover Cleveland High School in Buffalo, New York. The town of Cleveland, Mississippi is also named after him. Mount Cleveland, a volcano in Alaska, carries his name too. In 1895, he became the first U.S. president to be filmed.

The first U.S. postage stamp honoring Cleveland came out in 1923. Cleveland's picture was on the U.S. $1000 bill from 1928 and 1934. He also appeared on the first few issues of the $20 Federal Reserve Notes from 1914. Since he was both the 22nd and 24th president, he was featured on two different dollar coins in 2012. These were part of the Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005.

In 2013, Cleveland was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

Images for kids

-

Cleveland's first Cabinet. Front row, left to right: Thomas F. Bayard, Cleveland, Daniel Manning, Lucius Q. C. Lamar Back row, left to right: William F. Vilas, William C. Whitney, William C. Endicott, Augustus H. Garland

-

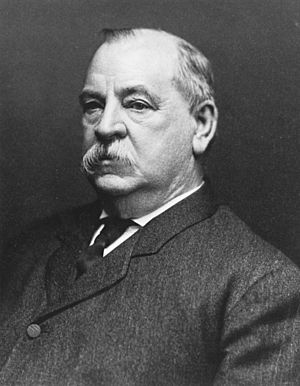

Official portrait of President Cleveland by Eastman Johnson, c. 1891

-

Cleveland's last Cabinet. Front row, left to right: Daniel S. Lamont, Richard Olney, Cleveland, John G. Carlisle, Judson Harmon Back row, left to right: David R. Francis, William Lyne Wilson, Hilary A. Herbert, Julius S. Morton

See also

In Spanish: Grover Cleveland para niños

In Spanish: Grover Cleveland para niños

- Grover Cleveland Birthplace

- Presidencies of Grover Cleveland

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |