Thomas A. Hendricks facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas A. Hendricks

|

|

|---|---|

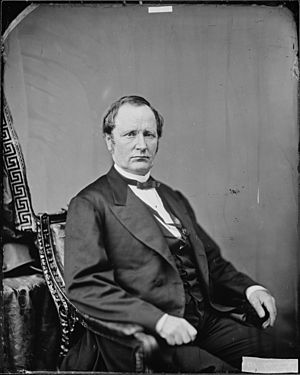

Portrait by Jose Mora, 1875

|

|

| 21st Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1885 – November 25, 1885 |

|

| President | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | Chester A. Arthur |

| Succeeded by | Levi P. Morton |

| 16th Governor of Indiana | |

| In office January 13, 1873 – January 8, 1877 |

|

| Lieutenant | Leonidas Sexton |

| Preceded by | Conrad Baker |

| Succeeded by | James D. Williams |

| United States Senator from Indiana |

|

| In office March 4, 1863 – March 3, 1869 |

|

| Preceded by | David Turpie |

| Succeeded by | Daniel D. Pratt |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Indiana |

|

| In office March 4, 1851 – March 3, 1855 |

|

| Preceded by | William Brown |

| Succeeded by | Lucien Barbour |

| Constituency | 5th district (1851–1853) 6th district (1853–1855) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Thomas Andrews Hendricks

September 7, 1819 Fultonham, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | November 25, 1885 (aged 66) Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Crown Hill Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Eliza Morgan |

| Children | Morgan Hendricks (1848–1851) |

| Education | Hanover College (BA) |

| Profession | Attorney |

| Signature | |

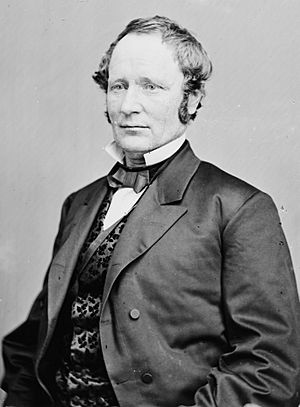

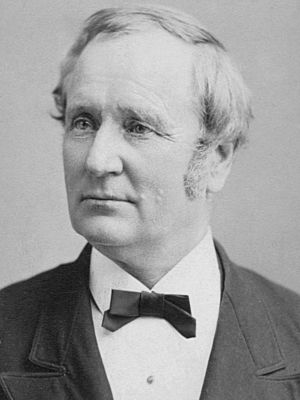

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819 – November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from Indiana. He held several important roles, including the 16th Governor of Indiana from 1873 to 1877. He also served as the 21st Vice President of the United States from March 1885 until his death in November of the same year.

Hendricks represented Indiana in the U.S. House of Representatives (1851–1855) and the U.S. Senate (1863–1869). He was also a delegate to Indiana's 1851 constitutional convention. For a time, he was a commissioner for the General Land Office, which managed government land sales.

As a popular member of the Democratic Party, Hendricks believed in careful government spending. During the American Civil War and Reconstruction era, he defended the Democratic viewpoint in the U.S. Senate. He voted against the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. These amendments aimed to end slavery and grant voting rights. He also opposed the idea of "Radical Reconstruction" and the attempt to remove President Andrew Johnson from office.

Born in Muskingum County, Ohio, Hendricks moved to Indiana with his family in 1820. They settled in Shelby County in 1822. After graduating from Hanover College in 1841, he studied law. He became a lawyer in Indiana in 1843. Hendricks started his law practice in Shelbyville, Indiana, and later moved to Indianapolis in 1860.

He ran for Indiana's governor three times, winning on his third try in 1872. His time as governor was challenging due to a strong Republican legislature and an economic downturn called the Panic of 1873. One of his lasting achievements as governor was starting talks to fund the building of the current Indiana Statehouse.

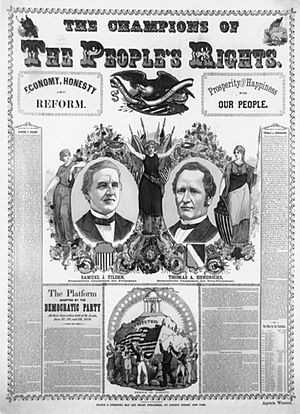

Hendricks was the Democratic candidate for U.S. vice president in the election of 1876 with Samuel J. Tilden as the presidential nominee. Even though they won the popular vote, they lost the election by one vote in the Electoral College. Despite his poor health, Hendricks accepted the vice presidential nomination again in the election of 1884 with Grover Cleveland. They won, but Hendricks only served for about eight months before he passed away in November 1885. He is buried in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas Andrews Hendricks was born on September 7, 1819, in Muskingum County, Ohio. He was the second of eight children born to John and Jane Hendricks. His father was from Pennsylvania, and his mother was from Virginia.

In 1820, when Thomas was young, his family moved to Madison. They were encouraged by Thomas's uncle, William Hendricks, who was a successful politician. William Hendricks served as a U.S. Representative, a U.S. Senator, and the third governor of Indiana. Thomas's family first lived on a farm near his uncle's home. In 1822, they moved to Shelby County, Indiana.

Thomas's father was a successful farmer and ran a general store. He also became involved in politics. Leaders of Indiana's Democratic Party often visited the Hendricks home in Shelbyville. This early exposure to politics influenced young Thomas.

Hendricks went to local schools, including Shelby County Seminary and Greensburg Academy. He graduated from Hanover College in Hanover, Indiana, in 1841. Another future Indiana governor, Albert G. Porter, was in the same class. After college, Hendricks studied law with Judge Stephen Major in Shelbyville. In 1843, he took an eight-month law course at a school run by his uncle, Judge Alexander Thomson, in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Hendricks then returned to Indiana, became a lawyer in 1843, and started his own law practice in Shelbyville.

Family Life

Hendricks married Eliza Carol Morgan on September 26, 1845. They had known each other for two years. Eliza was visiting her sister in Shelbyville when they met.

Thomas and Eliza had only one child, a son named Morgan, who was born in 1848. Sadly, Morgan died in 1851 at the age of three. In 1860, Thomas and Eliza Hendricks moved to Indianapolis. From 1865 to 1872, they lived at 1526 South New Jersey Street, a house now known as the Bates-Hendricks House.

Early Political Career

Hendricks was involved in law and politics from the 1840s until his death in 1885.

Serving in Indiana

Hendricks started his political career in 1848. He served a one-year term in the Indiana House of Representatives. He won against the Whig candidate, Martin M. Ray.

Hendricks was also one of two delegates from Shelby County to the Indiana constitutional convention in 1850–51. He helped create the rules for how the state's townships and counties would be organized. He also worked on the parts of the state constitution about taxes and money. Hendricks also spoke about the powers of different government offices. He supported a strong court system and wanted to get rid of grand juries.

U.S. Congressman

Hendricks represented Indiana as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1851 to 1855. He was chairman of the U.S. Committee on Mileage for a time.

He supported the idea of popular sovereignty, which meant letting people in new territories decide if they wanted slavery. He voted for the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed slavery to expand into western U.S. territories. These positions were not popular in his home district in Indiana. Because of this, he lost his re-election bid for Congress in 1854.

Land Office Commissioner

In 1855, President Franklin Pierce appointed Hendricks as commissioner of the General Land Office in Washington, D.C.. This office was in charge of managing government land. It was a very busy job because many people were moving west, and the government was selling a lot of land. Hendricks oversaw 180 clerks and a large amount of unfinished work.

During his time there, the land office issued 400,000 land ownership papers and settled 20,000 disagreements over land claims. Hendricks made thousands of decisions, and only a few were overturned by courts. He resigned from this role in 1859. The exact reason is not known, but it might have been because he disagreed with President James Buchanan, who became president after Pierce. Hendricks did not like Buchanan's efforts to use land office jobs for political favors. He also opposed Buchanan's pro-slavery policies and supported a bill that would give free land to settlers, which Buchanan did not like.

Running for Indiana Governor

Hendricks ran for governor of Indiana three times. He finally won on his third try in 1872. He became the first Democrat to be elected governor after the American Civil War.

In 1860, Hendricks lost to the Republican candidates, Henry Smith Lane and Oliver P. Morton. Three of these four men (Lane, Morton, and Hendricks) later became Indiana's governor. All four also became U.S. senators.

In 1868, his second campaign for governor, Hendricks lost to Conrad Baker by a very small number of votes. Baker later became one of Hendricks's law partners. Even though Hendricks lost, the close race showed how popular he was in Indiana. After this defeat, Hendricks left the U.S. Senate in March 1869 and returned to his law practice. However, he remained involved in state and national politics.

In 1872, in his third attempt to become governor, Hendricks won by a narrow margin against General Thomas M. Browne.

Law Practice

Besides his political roles, Hendricks kept his law practice active. He started it in Shelbyville in 1843 and continued it after moving to Indianapolis. In 1862, Hendricks and Oscar B. Hord started a law firm. Hendricks worked there until he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1863.

The law firm changed names over the years. In 1873, it became Baker, Hord, and Hendricks, after Conrad Baker joined. This firm eventually became Baker & Daniels, which grew into one of Indiana's leading law firms.

High Office

U.S. Senator

Hendricks served as a U.S. Senator for Indiana from 1863 to 1869. This was during the last years of the American Civil War and part of the Reconstruction era. He won election to the Senate partly because of difficulties in the Civil War and some unpopular decisions by President Lincoln. Also, the Democratic Party controlled the Indiana General Assembly at the time.

During his six years in the Senate, Hendricks was a leader of the small Democratic minority. He often disagreed with the majority. He spoke out against what he saw as extreme laws, such as the military draft and printing "greenbacks" (paper money). However, he supported the Union and the war effort, always voting for war funding.

Hendricks strongly opposed "Radical Reconstruction." He argued that the Southern states had never truly left the Union. Therefore, he believed they should have been allowed to send representatives to Congress right away. He also felt that Congress should not interfere with state governments.

Hendricks voted against the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. These amendments aimed to abolish slavery and grant voting rights to all men, regardless of race. Hendricks felt it was too soon after the Civil War to make such big changes to the Constitution. While he supported freedom for African Americans, he did not believe in racial equality.

He also opposed the effort to remove President Andrew Johnson from office after the House of Representatives tried to impeach him. When Republicans gained control of the Indiana General Assembly in 1868, Hendricks lost his bid for a second Senate term.

Governor of Indiana

In 1872, Hendricks was elected as the governor of Indiana. This was his third time running for the office. His growing popularity was clear during the presidential election of 1872. When the Democratic presidential candidate, Horace Greeley, died after the election but before the Electoral College voted, 42 of 63 Democratic electors voted for Hendricks instead.

Hendricks served as governor from January 13, 1873, to January 8, 1877. This was a difficult time because of an economic depression that followed the financial Panic of 1873. Indiana faced high unemployment, businesses failing, worker strikes, and falling farm prices. Governor Hendricks had to call out the state militia twice to end workers' strikes.

Even though Hendricks helped pass laws for election and court reform, the Republican-controlled legislature stopped many of his other goals. In 1873, he signed a controversial law about alcohol sales, even though he preferred a different approach. He signed it because he believed it was constitutional and reflected the will of the legislature and the people. This law was difficult to enforce and was later replaced by the system Hendricks had originally favored.

One of Hendricks's lasting achievements as governor was starting discussions to fund the building of a new Indiana Statehouse. The old building was too small and falling apart. The cornerstone for the current state capitol building was laid in 1880, after Hendricks left office. He gave the main speech at the ceremony. The new statehouse was finished eight years later and is still used today.

Vice Presidential Nominee

Hendricks ran for vice president in 1876 and 1884, winning in 1884. He was also nominated in 1880, but he declined due to health reasons. In 1880, he suffered a period of paralysis while visiting Hot Springs, Arkansas. He returned to public life, but his declining health was kept private by his family and doctors. Two years later, he could no longer stand.

In the disputed presidential election of 1876, Hendricks was the Democratic candidate for vice president. Samuel J. Tilden was the presidential nominee. Hendricks did not attend the Democratic convention. The party's plan was to win the Southern states, along with New York and Indiana. The Indiana group strongly supported Hendricks for vice president, and he was nominated without anyone voting against him.

Tilden and Hendricks won the popular vote. However, they lost the election by one vote in the Electoral College. This was a very controversial election. A special fifteen-member commission decided the outcome of the disputed electoral votes. In a close vote, the commission gave all twenty disputed votes to the Republican candidates, Rutherford B. Hayes and William A. Wheeler. Tilden and Hendricks accepted the decision, even though they were very disappointed.

As the leader of the Indiana group, Hendricks attended the Democratic Party's national convention in 1884 in Chicago. He was again nominated as the vice presidential candidate by a unanimous vote. Grover Cleveland was the party's presidential nominee. The Democrats' plan was again to win New York (Cleveland's home state), Indiana (Hendricks's home state), and the Southern states. They narrowly won New York, Indiana, and two other Northern states, plus the South, to win the election.

Vice Presidency (1885)

Hendricks had a good working relationship with President Cleveland during his short time in office. He spoke highly of Cleveland. Hendricks had been in poor health for several years. He served as Cleveland's vice president for about eight months. He was inaugurated on March 4, 1885, and died on November 25, 1885. The vice presidency remained empty after Hendricks's death until Levi P. Morton took office in 1889.

On September 8, 1885, in Indianapolis, Hendricks gave a speech supporting Irish independence. Soon after, a politician named Martin Lomasney named the Hendricks Club after him.

Death and Legacy

Hendricks died suddenly from a heart attack on November 25, 1885, while at home in Indianapolis. He had felt ill the day before and died in his sleep at age 66. His last reported words were "Free at last!"

His funeral service in Indianapolis was very large. Hundreds of important people attended, including President Grover Cleveland. Thousands of people lined the city streets to see the long funeral procession. It traveled from downtown Indianapolis to Crown Hill Cemetery, where he was buried.

Hendricks was a popular member of the Democratic Party. He got along well with both Democrats and Republicans. He believed in careful government spending and was known for being honest and having strong beliefs.

Hendricks was one of four vice-presidential candidates from Indiana who were elected between 1868 and 1920. During this time, Indiana's votes were very important for winning a national election. The other three vice presidents from Indiana during this period were Schuyler Colfax, Charles W. Fairbanks, and Thomas R. Marshall.

Honors and Tributes

- Hendricks is the only vice president who did not become president whose picture appears on U.S. paper money. His portrait is on a $10 "tombstone" silver certificate. It's called "tombstone" because of the shape around his picture.

- The Bates-Hendricks House, where his family lived from 1865 to 1872, is in Indianapolis. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

- The Thomas A. Hendricks Library (Hendricks Hall) at Hanover College was built in 1903. Hendricks's wife, Eliza, paid for it to honor her late husband, who was a graduate of the college. The library was added to the National Register in 1982. Pictures of Thomas and Eliza Hendricks hang inside the library.

- The Thomas A. Hendricks Monument was placed on the southeast corner of the state capitol building's grounds in 1890. It is the tallest bronze statue on the statehouse grounds.

- The community of Hendricks in Minnesota and the nearby lake were named after him.

Election Results

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Thomas A. Hendricks | 189,242 | 50.1 | |

| Republican | Thomas M. Browne | 188,276 | 49.9 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Conrad Baker | 171,575 | 50.1 | |

| Democratic | Thomas A. Hendricks | 170,614 | 49.9 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Henry Smith Lane | 139,675 | 51.8 | |

| Democratic | Thomas A. Hendricks | 129,968 | 48.2 | |

See also

In Spanish: Thomas A. Hendricks para niños

In Spanish: Thomas A. Hendricks para niños

- List of governors of Indiana

- Thomas A. Hendricks Monument

- Hendricks, West Virginia, a town named after him