Seacoast defense in the United States facts for kids

For a long time, protecting its coasts was a big deal for the United States. Before airplanes existed, most enemies could only attack America from the sea. This made building strong forts along the coast a smart and cheaper way to defend the country, instead of having huge armies or a giant navy. After the 1940s, people realized that fixed forts weren't very useful against modern airplanes and missiles. However, in earlier times, foreign ships were a real danger. So, many strong forts were built in important places, especially to protect big harbors.

These defenses mainly used forts, but they also included underwater minefields, nets, and barriers. Ships and airplanes also helped. All parts of the armed forces worked together for coastal defense. But the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers played the main role in building these fixed defenses.

The designs of these forts changed over time. They became old-fashioned as new technologies appeared for both attackers and defenders. Historians often divide the history of U.S. coastal defense into different "systems." These systems are partly defined by the building styles. But they are mostly defined by events or trends that led to new money and construction. The first two systems, called the First and Second Systems, were named by historians later on. This naming appeared officially in an 1851 report by Chief Engineer Joseph Gilbert Totten. He was probably the most active builder of stone forts in American history.

Contents

- Early Coastal Defenses

- Civil War Changes (1861-1865)

- After the Civil War to the Endicott Period (1867-1895)

- Taft Board and the Coast Artillery Corps (1905-1917)

- World War I (1914-1918)

- Between World War I and World War II (1918-1941)

- World War II (1941-1945)

- Postwar Defensive Missiles

- Images for kids

Early Coastal Defenses

At the start of the American Revolutionary War, many forts already protected the Atlantic coast. Before America became independent from Britain, the colonies paid for and were responsible for their own protection. How urgent defense was depended on what was happening in Europe. Most defenses were artillery protected by earthworks. These were built to guard against pirate raids and attacks from other countries. In the American colonies and later the United States, coastal forts were usually built stronger than forts inland. They had heavier weapons, similar to those on enemy ships. Even though they were rarely used, these forts helped scare off attackers. During the Revolution, both sides built more forts, usually for specific threats. The forts built by Patriot forces were called Patriot batteries.

First System Forts (1794-1807)

When the United States became independent in 1783, its coastal forts were in bad shape. In 1793, war broke out in Europe, which worried the U.S. government. So, the Congress created a group of "Artillerists and Engineers" in 1794. Their job was to design, build, and guard forts. Congress also set aside money to build several forts. These forts became known as the First System.

Twenty important forts were approved for construction at thirteen harbors. Most were traditional low-walled structures. They had gently sloped earthworks protecting walls made of wood or brick. The idea was that soft earth would absorb cannon fire, and low walls would be harder to hit. The walls were built at angles to each other, forming a star shape. This way, enemies couldn't gather at the base of a wall without being shot at from other walls. Angled walls also made it harder for cannonballs to hit straight on. Most First System forts were small. With a few exceptions, they only had one level of cannon on the roof. Extra "water batteries" (near the water the forts protected) outside the forts added more firepower. Four First System forts were rebuilt from older colonial forts: Fort Constitution in New Hampshire, Fort Independence in Massachusetts, Fort Wolcott in Rhode Island, and Fort Mifflin in Philadelphia.

The U.S. didn't have many trained engineers. So, Secretary of War Henry Knox hired engineers from Europe. Some good forts were built, but generally, interest and money ran out. Most of the unfinished earthworks and wooden structures fell apart before they were needed to fight the British in the War of 1812.

Second System Forts (1807-1812)

In 1802, Congress split the artillerists and engineers into separate groups. They told the Corps of Engineers to create a military academy at West Point, New York. A big reason for this new academy was to stop relying on foreign engineers. In 1807-1808, worries about a possible war with Great Britain made President Thomas Jefferson restart the fort-building programs. This became known as the Second System. One event that hinted at war was the Chesapeake–Leopard affair.

A common problem with the typical low-walled, open, star-shaped forts was that they were exposed to enemy fire. This was especially true with new bombs that exploded in the air and rained shrapnel down on the gunners. Cannon emplacements that were angled towards the sea were also at risk. A single cannonball fired parallel to the wall could take out a whole row of guns and gunners. In the late 1770s, a French engineer named the Marquis de Montalembert suggested a big change in fort design. His idea was to protect gunners by putting most of them in covered casemate walls with openings for the guns. By stacking rows of casemates in high walls, more guns could be placed along shorter walls. This was very important for coastal forts, which had only a short time to shoot at passing enemy ships. To build these tall forts, the walls had to be made of thick masonry to withstand cannon fire. Even though the goal was to build multi-tiered forts, only a few were finished, like Castle Williams in New York Harbor. Most completed Second System forts looked like First System forts, with one level of guns in a star shape, plus water batteries.

The Second System was different from the First because it used more of Montalembert's ideas. Also, American engineers, many of them new graduates from the United States Military Academy, replaced foreign engineers. Major Jonathan Williams led this effort. He taught the new engineers about coastal defense and designed a test fort, Castle Williams on Governors Island in New York Harbor.

Again, some good forts were built, but many projects were left unfinished. Between the First and Second Systems, not much was ready to fight the British in the coming War of 1812. However, no First or Second System fort was captured by the British. The British did get into Chesapeake Bay by capturing a fort on Craney Island near Norfolk. They then went around the area's other two forts. The invasion of Baltimore was stopped by Fort McHenry and other forts and troops. These included shoreline batteries at Forts Babcock and Covington, a temporary naval battery at Lazaretto Point, and sunken ships blocking the channels. Also, 20,000 militia soldiers were dug in on the east side of town. The intense all-night bombing of Fort McHenry by British ships was remembered by Francis Scott Key. He was a Baltimore lawyer who saw the attack from a ship. He wrote a four-stanza poem about watching the attack, which failed to destroy the fort or defeat its defenders. This poem became known as The Star-Spangled Banner and later became America's national anthem. Sometimes, even unfinished forts (some with fake wooden cannons painted black) were enough to stop attacks from the sea. But Washington, D.C., the capital, was undefended and burned after the land militia forces were defeated at the Battle of Bladensburg. Washington had one fort, Fort Washington, on the Potomac River. Its commander blew up the fort's gunpowder when the British fleet appeared, after the British had already taken Washington. The current Fort Washington was built on the same spot in the early 1820s as part of the Third System. Many important documents, including plans for the first Fort Washington and other Second System forts, were lost when the British burned the Library of Congress.

Third System Forts (1816-1867)

After the War of 1812, in 1816, Congress set aside over $800,000 for a big coastal defense plan called the Third System. A group of engineers, chosen by President James Madison, visited possible locations and made plans for the new forts. Their first report in 1821 set the rules for most of the 1800s. The report suggested 50 locations, but by 1850, the board had found almost 200 places for forts. The Army built forts at 42 of these places, with a few more having towers or batteries.

These forts were originally meant to hold mostly 42-pounder (7-inch) coastal guns. However, because there weren't enough of these weapons, many 32-pounder (6.4-inch) coastal guns and 8-inch and 10-inch Columbiads were used instead.

The main defenses were often large buildings. They combined the ideas of Montalembert, with many guns in tall, thick stone walls, and Vauban, with layers of low, protected stone walls. Most Third System forts had at least two levels of cannons. First and Second System forts often had only one level. Officers from the Army's Corps of Engineers usually supervised the construction. Smaller defenses guarded less important harbors. U.S. Army engineer Joseph Gilbert Totten and former French engineer Simon Bernard designed the larger forts and key parts of most smaller forts. This included the Totten casemate, which allowed a good firing range with a small opening.

By the end of the Third System in 1867, 42 forts protected the main harbors along the coast. Most of the forts were finished, but some, mostly in New England, were still being built. A few of these, like Fort Preble, Fort Totten, and Fort Constitution, were made ready for weapons even though they were far from complete.

The Corps of Engineers listed the forts from Northeast to Southwest, then to the Pacific Coast. Here are some of the new forts built during the Third System:

- Maine: Fort Knox, Fort Popham, Fort Gorges, Fort Scammell, Fort Preble

- New Hampshire: Fort McClary, Fort Constitution

- Massachusetts: Fort Warren, Fort Independence, Fort at Clark's Point (later Fort Rodman)

- Rhode Island: Fort Adams

- Connecticut: Fort Trumbull

- New York: Fort Schuyler, Fort at Willets Point (later Fort Totten), Fort Tompkins, Fort Richmond, Fort Hamilton, Fort on Sandy Hook, New Jersey (later Fort Hancock)

- Delaware: Fort Delaware

- Maryland: Fort Carroll, Fort Washington

- Virginia: Fort Monroe, Fort Calhoun (later Fort Wool)

- North Carolina: Fort Macon, Fort Caswell

- South Carolina: Fort Sumter

- Georgia: Fort Pulaski

- Florida: Fort Clinch, Fort Taylor, Fort Jefferson, Fort Pickens, Fort Barrancas, Advanced Redoubt, Fort McRee

- Alabama: Fort Morgan, Fort Gaines

- Louisiana: Fort Massachusetts, Fort Pike, Fort Wood (later Fort Macomb), Fort Jackson, Fort St. Philip, Fort Livingston

- California: Fort Point, Fort Alcatraz

Older First and Second System forts were also updated during this time to hold the larger cannons that were common.

Civil War Changes (1861-1865)

Technology kept changing, and new rifled cannons could fire faster and hit harder. These new guns could crush and break through the stone walls of Third System forts. Forts on the Atlantic Coast were badly damaged during the American Civil War. For example, Fort Sumter in South Carolina was bombed until it surrendered to Confederate forces in 1861. It was then turned into rubble during Union attempts to get it back. In 1862, Fort Pulaski in Georgia had to surrender after only 30 hours of bombing with rifled cannons, mostly large Parrott rifles.

Many of the larger smoothbore cannons (32-pounder and up) were changed to have rifled barrels and metal bands around them. This allowed them to use more gunpowder and shoot farther during the Civil War. This process was called "banded and rifled."

During the Civil War, naval officers learned that their steamships and ironclad vessels could pass Confederate forts with acceptable losses, like at Battle of Mobile Bay.

The urgency of war meant that new forts or improvements had to be built quickly and cheaply. Partially finished Third System forts were completed. But new construction mostly involved earthworks reinforced with wood. Often, earthworks were built near a Third System fort to add more firepower. But sometimes, they were stand-alone forts. In some cases, cannons from stone forts were moved to earthen bunkers where they were better protected. The defenses of San Francisco Bay are a good example. The typical Third System Fort Point at the bay's entrance was effectively replaced by spread-out earthworks and low-walled forts nearby on Alcatraz Island, Angel Island, the Marin Headlands, and Fort Mason. After the war, work on stone forts stopped in 1867, leaving several unfinished.

Underwater Mines

Robert Fulton used the word "torpedo" in 1805 to describe an underwater explosive device. Samuel Colt experimented with making torpedoes explode using electricity. During the Civil War, these underwater mines became an important extra defense. The Confederacy, which didn't have a big navy to protect its harbors, used mines a lot to stop Union ships from attacking. Electrically fired torpedoes, later called mines, were controlled from special rooms on shore. They were developed during and after the Civil War as part of coastal defenses.

Civil War Coastal Cannons

Many types of coastal cannons were used in the Civil War. Here are some of the widely used ones:

- Smoothbore cannons:

- 32-pounder (6.4-inch) and 42-pounder (7-inch) coastal guns

- 8-inch and 10-inch columbiads

- 8-inch, 10-inch, 15-inch, and 20-inch Rodman guns (a type of columbiad)

- Rifled cannons:

- Rifled and sometimes banded versions of smoothbore guns, from 24-pounder (5.82-inch) to 10-inch size. One Union rifling system was called the James rifle.

- 6.4-inch (100-pounder), 8-inch (200-pounder), and 10-inch (300-pounder) Parrott rifles

- 6.4-inch and 7-inch Brooke rifles (made by the Confederacy)

After the Civil War to the Endicott Period (1867-1895)

After the war, construction began on several new Third System forts in New England. These were to be built of stone instead of brick and designed for the large cannons developed during the war. However, in 1867, money for stone forts was stopped, and the Third System ended.

Because stone forts were easily damaged by rifled cannons and large smoothbore cannons, and with less worry about invasion, new defenses were built. These were earthworks reinforced with stone and brick-lined storage rooms for gunpowder. They were often near Third System forts. These new defenses usually had 15-inch Rodman guns and 8-inch converted rifles. In some cases, older forts were also rearmed with these weapons. Most of the larger Parrott rifles had burst often during the war, so few were kept in service afterward. Also, in the 1870s, new projects started to include large mortars and underwater mines. However, the places for these mortars and mines were never finished, and funding for new forts was cut off by 1878. By the 1880s, most of the earthen defenses were falling apart.

Monitors for Coastal Defense

Even though coastal defense was usually the Army's job, the Navy became more involved in the late 1800s with coastal defense ships, often called monitors. These monitors were armored warships with rotating gun turrets, inspired by USS Monitor. Besides ships that looked just like the Monitor, the term "monitor" also included more flexible ships with a small armored structure, which made them better at sea. These also had modern rifled guns that loaded from the back.

Monitor-style ships were used a lot in attacks during the Civil War. But they weren't practical for ocean travel or attacking abroad. However, they were perfect for harbor defense because they didn't need deep water and had big guns. After the war, Civil War-era monitors were sent to important harbors, including San Francisco on the west coast. From the 1870s to the 1890s, larger and more powerful monitors were built, like the Amphitrite class. Meanwhile, the ocean-going navy was slow to switch to steel hulls and armor. An improved monitor idea was the coastal battleship, like the Indiana class of the 1890s.

After the Spanish–American War and the U.S. gained Hawaii and the Philippines, the Navy decided by 1900 to focus on ocean-going battleships. They stopped building monitors. However, some monitors stayed in service until World War I for combat, and as training or support ships afterward.

Endicott Period Forts (1895-1905)

As early as 1882, people realized the U.S. needed strong, fixed cannons for coastal defense. Previous efforts to build harbor defenses had stopped in the 1870s. Since then, the design of heavy weapons in Europe had improved quickly. They developed better cannons that loaded from the back and shot farther. This made U.S. harbor defenses old-fashioned. In 1883, the Navy started building new ships, focusing on attacking rather than defending. All these things together created a need for better coastal defense systems.

In 1885, President Grover Cleveland appointed a group of Army, Navy, and civilian experts. This group, led by Secretary of War William Crowninshield Endicott, was called the Board of Fortifications. Their report in 1886 showed how bad the existing defenses were. They suggested a huge $127 million plan to build breech-loading cannons, mortars, floating batteries, and underwater mines for 29 locations along the U.S. coast. Most of the board's ideas were accepted. This led to a big update of U.S. harbor and coastal defenses. They built modern reinforced concrete forts and installed large, breech-loading cannons and mortar batteries. Usually, Endicott period projects were not single fortresses. Instead, they were a system of spread-out gun positions, with a few large guns in each spot. The structures were typically open-topped concrete walls protected by sloped earthworks. Many of these had disappearing guns. These guns stayed hidden behind the walls but could be raised to fire. Except for a few early projects, Endicott forts had no strong defenses against attacks from land. Controlled mine fields were a very important part of the defense. Smaller guns were also used to protect the mine fields from minesweeping vessels. A detailed fire control system was developed for the forts in each area. Most Endicott forts were built between 1895 and 1905. As the defenses were built, the forts in each harbor or river were controlled by Artillery Districts. These were renamed Coast Defense Commands in 1913 and Harbor Defense Commands in 1925.

By the start of the Spanish–American War in April 1898, only a few batteries at each harbor were finished from the Endicott Program. After the USS Maine sank on February 15, Congress approved building batteries that could be quickly armed at many East Coast locations on March 9, 1898. People feared the Spanish fleet would bomb U.S. ports. Finishing Endicott batteries and fixing or moving 1870s batteries were also part of the plan. The 1870s batteries used Civil War-era Rodman guns and Parrott rifles, along with some new weapons. New batteries were also started for eight 6-inch Armstrong guns and 34 4.72-inch Armstrong guns, bought from the United Kingdom. These provided some modern, fast-firing medium-sized guns, as none of the Endicott Program's 6-inch or 3-inch batteries were ready. Field artillery, mainly 5-inch siege guns and 7-inch siege howitzers, was also used, mostly in Georgia and Florida. Many of these batteries weren't finished until 1899, after the war ended. The 8-inch guns were removed within a few years as modern places for them were completed.

Coast Artillery Corps (1901)

Army leaders realized that heavy fixed artillery needed different training and tactics than mobile field artillery. Before 1901, each of the seven artillery regiments had both heavy and light artillery. In February 1901, with the Endicott program well underway, the Artillery Corps was split into two types: field artillery and coast artillery. The old seven artillery regiments were dissolved. Instead, 30 numbered companies of field artillery and 126 numbered companies of coast artillery (CA) were approved. 82 existing heavy artillery batteries became coast artillery companies. 44 new CA companies were created by splitting existing units and adding new recruits. This company-based organization allowed flexibility, as each harbor defense command was equipped differently. The Coast Artillery would switch between small unit and regimental organization several times in its history. The head of the Artillery Corps became the Chief of Artillery, a brigadier general, in charge of both types of artillery.

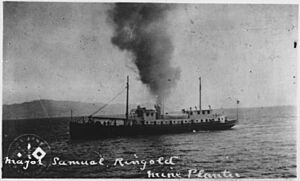

Mine Planter Ships

Around 1901, the Coast Artillery took over the job of setting up and running the controlled mine fields from the Corps of Engineers. These mines were placed to be watched, exploded remotely by electricity, and protected by fixed guns. With this new job, the Coast Artillery started getting ships to place and maintain the mine fields and the cables connecting the mines to the mine control room on shore. This was organized as a "Submarine Mine Battery" within the coast defense command. The larger ships, called "mine planters," had civilian crews until the U.S. Army Mine Planter Service (AMPS) was created in 1918. This service provided officers and engineers for these ships. The mine part of the defense was considered one of the main weapons of coastal defense. When the Coast Artillery Corps was closed down and the artillery branches combined in 1950, some mine planter ships were given to the U.S. Navy and renamed Auxiliary Minelayers.

Endicott Period Coastal Cannons

These weapons were put in place between 1895 and 1905. Most, except for the mortars, 3-inch guns, and some 6-inch guns, were on disappearing carriages. These carriages allowed the guns to be hidden and protected behind walls, then raised to fire. Other guns used barbette carriages (also called pedestal carriages), which kept the gun on a fixed platform. Even though some harbor defenses in less-threatened areas were disarmed after World War I, many of these weapons stayed in service until they were replaced by 16-inch guns and scrapped during World War II.

Here are some of the widely used weapons from this period:

- 12-inch gun (305 mm)

- 12-inch mortar (305 mm)

- 10-inch gun (254 mm)

- 8-inch gun (203 mm)

- 6-inch gun (152 mm)

- 5-inch gun (127 mm)

- 3-inch gun (76 mm)

Taft Board and the Coast Artillery Corps (1905-1917)

In 1905, after the Spanish–American War, President Theodore Roosevelt created a new board for fortifications. This board, led by Secretary of War William Howard Taft, updated some rules and checked the progress of the Endicott Board's plan. Most of the changes suggested by this board were technical. For example, they recommended adding more searchlights, using electricity for lighting, communications, and moving projectiles, and more advanced ways to aim guns. The board also suggested building forts in new territories gained from Spain: Cuba and the Philippines, as well as Hawaii, and a few other places. Defenses in Panama were approved by the Spooner Act of 1902. The Taft Program forts were slightly different in how they were built and had fewer guns in each location than the Endicott Program forts. Because dreadnought battleships were developing quickly, a new 14-inch gun was introduced in a few places, and improved versions of other weapons were also used. By the start of World War I, the United States had a coastal defense system as good as any other country's.

The fast pace of technology and changing methods increasingly separated coastal defenses (heavy guns) from field artillery (light guns). Officers were rarely skilled enough to command both, so they needed to specialize. As a result, in 1907, Congress split Field Artillery and Coast Artillery into separate branches. This created a separate Coast Artillery Corps (CAC) and allowed for more Coast Artillery Corps companies. In 1907, the Artillery School at Fort Monroe became the Coast Artillery School, which operated until 1946. In 1908, the Chief of Artillery became the Chief of Coast Artillery.

In 1907, during an exercise in Subic Bay, Philippines, a U.S. Marine battalion quickly set up forty-four heavy guns for coastal defense in ten weeks. This happened because of worries about war with Japan. These guns were used by the Marines until about 1910, when the Coast Artillery Corps' modern defenses, centered on Fort Wint on Grande Island, were finished.

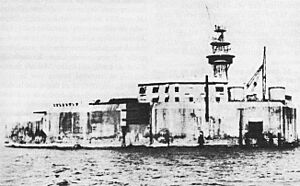

Fort Drum: A Unique Fortress

One of the most unusual forts of the early 1900s was Fort Drum in Manila Bay in the Philippines. It started as a bare rock island. Between 1910 and 1914, U.S. Army engineers flattened it and then built it up with thick layers of steel-reinforced concrete. It looked like a giant concrete battleship. It was the only true sea fort of the Endicott and Taft programs. The fort had two armored steel gun turrets on top, each with two 14-inch M1909 guns. These guns were made specially for Fort Drum and weren't used anywhere else. Four 6-inch M1908 guns were also installed in casemates. Searchlights, anti-aircraft batteries, and a fire control tower were also on its top surface. The 25 to 36-foot-thick walls of the fort protected large ammunition storage rooms, machine areas, and living quarters for the 200 soldiers. This high level of fortification was not typical for the time, but it was needed because of the fort's exposed location. Even though it was designed before air attacks were a big concern, the design turned out to be excellent for defending against them.

When war broke out in the Pacific on December 7, 1941, Fort Drum withstood heavy Japanese air and land bombing. It supported U.S. and Filipino defenders on Bataan and Corregidor until May 6, 1942. The fort was one of the last U.S. posts to hold out against the Japanese. It only surrendered when ordered by commanders after Corregidor had been taken. But not before the U.S. soldiers had damaged the guns and weapons to stop the Japanese from using them. Interestingly, even without the guns, the Japanese soldiers in Fort Drum were among the last to surrender when U.S. forces recaptured the Philippines in 1945.

World War I (1914-1918)

Submarines and airplanes became more important during World War I. Submarines were seen as a threat to U.S. harbors. This led to more use of mines and nets, and a demand for better artillery. However, as the war went on, it became clear that enemies couldn't easily bring the war across the Atlantic. So, progress slowed down. Oddly, even with the rise of air power in World War I, it wasn't a big factor in U.S. coastal defense design until the late 1930s. This was probably because Japanese aircraft carriers became a threat later. Because of fast improvements in dreadnought battleships, about 14 batteries, each with two 12-inch guns on new long-range carriages, began construction in 1917. But none were finished until 1920.

Because of their experience with large guns, the Coast Artillery operated all U.S. Army heavy artillery (155mm gun and up) in World War I. They mainly used French and British weapons. They also took on the anti-aircraft mission in that war. A number of 5-inch and 6-inch guns were taken from coastal defenses and put on wheeled carriages to be used on the Western Front. About 72 6-inch guns and 26 5-inch guns were sent to France. However, because of the Armistice, none of the units with these repurposed guns finished training in time to fight. Only a few of the 6-inch guns and none of the 5-inch guns were returned to coastal defenses after the war. Most of the 6-inch guns were stored until they were remounted in World War II. The 5-inch guns were declared old and scrapped around 1920.

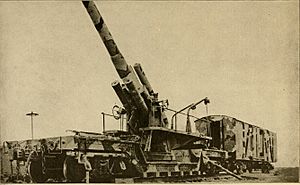

Railway Artillery

A big plan to put 12-inch mortars and 8-inch, 10-inch, and 12-inch guns on railway artillery was partly carried out during and after World War I. These weapons were taken from less-threatened forts and from spare parts. A plan to reduce mortars from four per pit to two per pit created extra weapons. The tight pits made reloading difficult; a two-mortar pit fired at about the same speed as a four-mortar pit. Despite a big effort, only three 8-inch guns were sent to France before the Armistice, due to shipping priorities. The mortars and 8-inch guns could be aimed in different directions, so they were good for coastal defense. The other weapons were returned to the forts after the war. Sources say that up to 91 12-inch mortars and 47 8-inch guns were kept as railway coastal defense weapons through World War II. Most of the 8-inch guns were used, and almost all the mortars were kept in reserve. During World War I, the U.S. Navy had a more successful program. They sent five 14"/50 caliber railway guns to France in time to help with the final Allied attacks. However, these weapons' mounts were not good for coastal defense, and they were retired after that war.

Between World War I and World War II (1918-1941)

Airplanes became a small but growing factor in World War I. The threat from planes led to changes in coastal defenses in the 1920s and 1930s. Demonstrations in the 1920s by U.S. Army General Billy Mitchell showed that warships could be damaged by air attacks. This showed how aircraft could be used for coastal defense against ships, but also how defenses could be vulnerable to air power. In the U.S., which was focused on its own country, bombers were seen more as a defense against naval attacks than as a strategic offensive weapon. However, planes like the Boeing B-17, which were developed for defense, turned out to be excellent for offense too.

Drawdown and Reorganization

In the early 1920s, several types of weapons were removed from Coast Artillery service, mostly those with only a few deployed. This was probably to make supplying them simpler. The only widely used type removed was the 3-inch M1898 gun with its masking parapet mounts. At least 111 of these had been installed. The disappearing function had already been turned off because it interfered with aiming the gun, and the weapon often had a problem where the piston rod would break when fired. Other weapons removed included 6-inch Armstrong guns (9 guns), all three types of 4.72-inch Armstrong guns (34 guns), 4-inch/40 caliber Navy guns (4 guns), and all models of 5-inch guns (52 guns). Twenty-six of the 5-inch guns had been sent to France for use on field carriages. Also, about 72 6-inch guns taken from coastal defenses for field service were not immediately put back. These were eventually put on long-range carriages in new batteries during World War II. Except in a few cases, these weapons were not directly replaced.

On June 9, 1925, the Coast Defense Commands were renamed Harbor Defense Commands by a War Department order. By the end of the 1920s, eight harbor defense commands in less-threatened areas were completely disarmed. These included places like the Kennebec River, ME, Baltimore, MD, and the Mississippi River, LA. It's possible their mine defenses were kept in reserve. Some of these commands were rearmed with "Panama mounts" for mobile artillery early in World War II.

In 1922, 274 Coast Artillery companies were approved, with 188 active. That year, 44 companies were closed, but 14 new companies were created for the Philippine Scouts, and a 15th in 1923. The Philippine Scouts, mostly Filipino soldiers with U.S. officers, manned many of the coastal defenses in the Philippines and served in other important roles. The Army's main staff confirmed that artillery and mines were the most practical and cost-effective ways for coastal defense. This was seen as an alternative to a larger Navy or Air Corps. In 1924, the CAC adopted a regimental system, combining the companies into 16 Regular Army harbor defense regiments, two Philippine Scouts regiments, three Regular tractor-drawn regiments, and two Regular railway regiments. These were supported by 11 harbor defense and two tractor-drawn regiments from the National Guard, who trained in peacetime for wartime. The total number of companies approved stayed the same, at 289 with 144 active. There was also a Coast Artillery Reserve of 14 harbor defense regiments, four railway regiments, three tractor-drawn regiments, and 42 anti-aircraft regiments in 8 AA brigades. However, many Reserve units had few personnel and were often closed without being activated during World War II. From 1930 to 1932, the army made new defense plans for each harbor. In 1931, it created a Harbor Defense Board to oversee these projects.

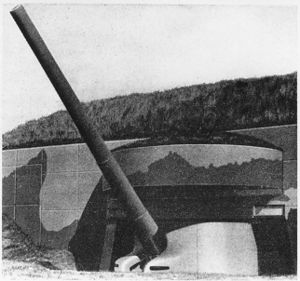

New Weapons and Air Defense

The rapid development of dreadnought battleships between 1905 and 1920 showed the need for better coastal defenses. Most Endicott and Taft period weapons were on short-range mounts and weren't big enough to reliably defeat battleship armor. Thirty existing 12-inch M1895 guns were put on new long-range M1917 barbette carriages in 16 batteries, including two single-gun batteries in the Philippines. Most of these batteries remained in service through the end of World War II. Other new weapons were used, but not many, because of budget limits. 14-inch M1920 railway guns were added to the harbor defenses of the Panama Canal and Los Angeles, two at each place. The future of U.S. coastal defense was hinted at with the adoption of 16-inch (406 mm) guns. These were initially the 16-inch howitzer M1920 (25 calibers long) and 16-inch gun M1919 (50 calibers long). Based on the Coast Artillery's experience with heavy weapons in World War I, new barbette carriages were designed to elevate the guns up to 65 degrees. This allowed for "plunging fire" as enemy ships approached. Four howitzers were placed at Fort Story, Virginia. Seven guns were placed at four locations near Boston, Long Island, NY, Queens, NY, and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. In 1922, the Washington Naval Treaty caused the U.S. Navy to cancel some battleships. This made 16-inch/50 caliber Mark II and Mark III gun barrels available. About 70 guns were finished before the treaty took effect, and the Navy wanted to keep most for future battleships. At first, only 20 guns were given to the Army, who built a new version of the M1919 mount for the naval guns. However, only ten of these guns were used until 1940, in Pearl Harbor, Panama, and San Francisco. They were known as the 16-inch Navy gun MkIIMI and MkIIIMI in Army service. The 16-inch guns, firing 2340 lb projectiles up to 49100 yd, were much more effective than any previous U.S. coastal defense guns.

Another weapon used sparingly in the 1930s would become a bigger part of World War II coastal defenses. 8-inch/45 caliber Mark VI naval guns from older battleships scrapped under the Washington Naval Treaty became available. But only six guns were used between 1933 and 1938, all in fixed mounts. Up to 32 guns were initially available from the secondary weapons of some battleships. They were known as the 8-inch Navy gun MkVIM3A2 in Army service, and a railway mount was developed in 1941.

Protection against air attack was slow to develop. Existing batteries were camouflaged, but if found, they were still vulnerable to air attack. The first batteries of heavy guns built after World War I were, strangely, completely open except for camouflage. But they had long-range weapons placed far back from the coast, out of direct view from the sea. However, from the late 1930s (mostly starting in 1942), these batteries were placed under thick concrete casemates covered with plants. This made them almost invisible from above and well protected against bombing. Importantly, the Washington Naval Treaty stopped major improvements to defenses in the Pacific, including the Philippines. So, the two long-range 12-inch guns at Fort Mills on Corregidor were never put in casemates. This probably made them more useful against the Japanese invasion, as they had wide firing arcs. Another result was that 12 240 mm howitzers being sent to the Philippines were instead used in Hawaii. Because of a possible conflict with Japan, most of the limited money available between 1933 and 1938 was spent on the Pacific coast. This was especially true as several Japanese aircraft carriers were active by then. In 1939, the threat of war in Europe led to more money and the restart of work along the Atlantic coast.

A new weapon adopted by the U.S. during World War I brought road and cross-country movement to the Coast Artillery. The 155 mm gun M1918 (6.1 inch), based on the French 155mm GPF, could be towed by heavy Holt tractors. It could be used to protect areas not covered by existing harbor defenses. Each tractor-drawn regiment had 24 of these weapons. Round concrete platforms called "Panama mounts" were built in existing and new defenses to make these weapons more useful, especially early in World War II.

Before the war, more mines, searchlights, radar, and anti-aircraft guns were installed in 1940 and 1941. However, because there weren't enough, few new anti-aircraft guns were put at harbor defenses. After the war began, the entire Western Defense Command was put on high alert. But Japanese attacks, including two submarine deck gun attacks and explosive balloons, caused only minor damage.

Anti-submarine nets, naval mines, and controlled mines protected many harbor entrances. Radar and patrol planes could find enemy ships far away, and aircraft became the first line of defense against intruders.

A coastal defense exercise in the Harbor Defenses of Long Island Sound in 1930 included aircraft and submarines in the defense plan. Observation, bombing, and fighter aircraft were included. The submarines had a dual mission of scouting and counter-attacking. It was decided that these missions should be separate in the future.

World War II (1941-1945)

The attack on Pearl Harbor showed that coastal artillery not protected against air attack was old-fashioned. It also showed that pre-war anti-aircraft defenses were not good enough. However, perhaps if there had been no coastal artillery, surface raiders would have been bolder. Coastal defense positions in the Philippines (the only time since the Civil War that U.S. coastal defenses were heavily involved) and Singapore were effective locally. However, the Japanese simply attacked where there were no defenses and then surrounded the forts. Heavily fortified places like Japanese Rabaul and Fort Drum in the Philippines showed tactical success even though the overall strategy failed.

Fall of the Philippines

The Japanese invaded the Philippines shortly after Pearl Harbor. This brought the Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays into the war, along with other U.S. and Filipino forces. The Japanese first landed in northern Luzon, far from the defenses of Manila Bay. Although the Coast Artillery did their best, their weapons were poorly placed for the direction of enemy attacks. They were also vulnerable to air and high-angle artillery attacks. Eight 8-inch railway guns had been sent to the Philippines in 1940. But six were destroyed by air attack while on trains responding to the initial landings. The other two were placed in fixed mounts on Corregidor and Bataan, but they lacked crews and ammunition. The 14-inch turret guns of Fort Drum and the 12-inch mortars of Battery Way and Battery Geary were probably the most effective coastal defense weapons in the Battle of Corregidor. But all but two of the mortars were knocked out before the Japanese landed on the island. The U.S. forces surrendered on May 6, 1942, after destroying their weapons.

Modernizing Coastal Defenses

The start of war in Europe in September 1939 and the Fall of France in June 1940 greatly sped up U.S. defense planning and funding. Around this time, a lack of design coordination meant that the Iowa-class battleship could not use the Mark 2 and Mark 3 16-inch guns, and a new gun design was needed for them. With war approaching, the Navy released about 50 remaining guns. On July 27, 1940, the Army's Harbor Defense Board suggested building 27 (eventually 38) 16-inch two-gun batteries. These would protect important points along the U.S. coastline and be protected against air attack, as almost all older batteries were by this time.

The 16-inch guns were just the biggest part of the World War II program. This program eventually replaced almost all older coastal defense weapons with newer ones (or older ones remounted). Most of the 12-inch long-range batteries were put in casemates and served until the end of the war. Generally, each harbor defense command was supposed to have two or three 16-inch or 12-inch long-range batteries, plus 6-inch guns on new mounts with protected magazines, and 90 mm Anti Motor Torpedo Boat (AMTB) guns. These were also supported by 37 mm or 40 mm anti-aircraft guns. In addition to the proposed 38 new 16-inch (406 mm) batteries with a range of 25 mi, eleven new 8-inch (203 mm) batteries with a range of 20 mi, and 87 new 6-inch (152 mm) batteries on high-angle shielded mounts with a range of 15 mi were planned. All these batteries had two guns each with heavily protected magazines and plotting rooms, and casemated guns (except the 6-inch guns had shielded mounts). Also, about 32 8-inch MkVIM3A2 railway guns were used. In most cases, these replaced existing harbor defenses.

As the war progressed and combat areas moved farther from the U.S., and as naval threats mostly disappeared, defending harbors against ships became a low priority. As the new coastal defense batteries were finished, almost all older coastal guns were scrapped to make new weapons. Many Coast Artillery soldiers were moved to field artillery, anti-aircraft, or even infantry duties. When the war ended, it was soon decided that coastal defense guns were no longer needed. Missiles would eventually take over that role. By 1947, most guns remaining in coastal defenses were declared extra and scrapped. The last weapons were removed in 1950 when the Coast Artillery was closed down.

Other Coastal Defense Operations

Two other parts of coastal defense early in the war were coastal beach patrols in the continental U.S. and keeping mobile forces there to respond to possible enemy raids. The Coast Guard started these patrols after Pearl Harbor. In early 1942, the Eastern and Western Defense Commands were given up to eight infantry regimental combat teams each for both beach patrols and mobile response. With a rapidly decreasing threat after 1942, by mid-1943 these forces were greatly reduced. Most were disbanded in early 1944. On the night of June 12, 1942, a Coast Guard sailor on patrol saw German agents landing from a U-boat near Amagansett, Long Island, New York. Communication problems prevented an immediate response. But the four agents were rounded up over the next two weeks, along with another four who landed near Jacksonville, Florida on June 17. Their capture was made easier when two of the agents in New York decided to turn themselves in within a few days. They were tried by a military court-martial. Six of the eight were executed. One of the defectors received a life sentence, and the other 30 years in prison.

Besides the Coast Artillery, important islands in the Pacific were defended by U.S. Marine defense battalions throughout the war. Their most famous fight was the Battle of Wake Island in December 1941. They caused heavy losses to a Japanese invasion force that eventually took the island. The U.S. Navy helped with harbor defense using anti-submarine nets and magnetic "indicator loops" for finding submarines. Joint harbor defense command posts were set up to coordinate Army and Navy operations. The 155 mm Long Tom artillery piece, an improved version of the 155mm GPF, was used in island and harbor defense in the Pacific from 1943 by both the Marines and the Army. Seven Army Coast Artillery Groups (155mm Gun) were activated in May–June 1944. Three were sent to Okinawa and the Philippines in 1945, while one was activated in Trinidad. The rest never left the U.S.

Postwar Defensive Missiles

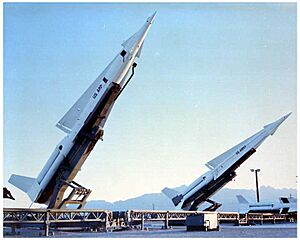

A system of 90 mm and 120 mm anti-aircraft guns was placed around the edges of the continental U.S. shortly after World War II. However, technology quickly moved past it. Early in the Cold War, the Soviet Union developed long-range bombers that could reach the United States. Soon after, they exploded their first atomic bomb. Harbors and naval bases were among the most threatened targets. The job of the Nike surface-to-air missile program was to be a "last-resort" air defense for selected areas. The Nike system would have been used if the Air Force's interceptor aircraft failed. With some ability to hit ships (especially the later nuclear-capable weapons), these were the last fixed-fortification weapons used in the United States.

Nike sites were built in the 1950s in "rings" around major cities, industrial areas, and key Strategic Air Command bases. The number of sites in each ring varied. In flat areas, rings usually had four launch sites, like in Washington, D.C. However, because of mountains, the San Francisco Bay area needed twelve launch sites. Because the original Nike missile, the Nike Ajax, had a short range, many bases were close to the center of the areas they protected. Often, they were in heavily populated areas. By 1960, the longer-range, nuclear-capable Nike Hercules was used, with the Air Force's BOMARC missile system following soon after.

With the arrival of many intercontinental ballistic missiles, the Nike and BOMARC systems were considered old-fashioned by the mid-1960s. The installations were removed in the early 1970s, ending nearly 200 years of American coastal defense.

Images for kids

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |