Chesapeake Bay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chesapeake Bay |

|

|---|---|

A satellite image of Chesapeake Bay

|

|

The Chesapeake Bay drainage basin extends into six states, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New York, and the federal capital of Washington, D.C.

|

|

| Location | Maryland and Virginia |

| Coordinates | 37°48′N 76°06′W / 37.8°N 76.1°W |

| Type | Estuary |

| Etymology | Chesepiooc, Algonquian for village "at a big river" |

| Primary inflows | Susquehanna River mouth east of Havre de Grace, Maryland |

| River sources | Deer Creek, Bush River, Gunpowder River, Back River, Patapsco River, Severn River, Patuxent River, Potomac River, Rappahannock River, York River, James River, Chester River, Choptank River, Nanticoke River, Pocomoke River |

| Primary outflows | Atlantic Ocean north of Virginia Beach, Virginia 36°59′45″N 75°57′34″W / 36.99583°N 75.95944°W |

| Catchment area | 64,299 sq mi (166,530 km2) |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 200 mi (320 km) |

| Max. width | 30 mi (48 km) |

| Surface area | 4,479 sq mi (11,600 km2) |

| Average depth | 21 ft (6.4 m) |

| Residence time | 180 days |

| Settlements | Annapolis, Baltimore, Cambridge, Cape Charles, Chesapeake, Chesapeake Beach, Elkton, Hampton, Havre de Grace, Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Virginia Beach |

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. An estuary is a place where fresh river water mixes with salty ocean water. The Bay is mostly separated from the Atlantic Ocean by a land area called the Delmarva Peninsula. This peninsula includes parts of Maryland, Virginia, and Delaware. The southern entrance to the Bay is between Cape Henry and Cape Charles.

The northern part of the Chesapeake Bay is in Maryland, and the southern part is in Virginia. It is very important for the nature and economy of these two states. More than 150 rivers and streams flow into the Bay. Its drainage basin (the land area that drains into it) covers about 64,299-square-mile (166,534 km2). This area includes parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia, plus all of Washington, D.C..

The Bay is about 200 miles (320 km) long. It stretches from the Susquehanna River in the north to the Atlantic Ocean. At its narrowest, it is 2.8 miles (4.5 km) wide. At its widest, it is 30 miles (48 km) wide. The total shoreline, including all the smaller rivers that flow into it, is about 11,684 miles (18,804 km) long. The Bay's surface area is about 4,479 square miles (11,601 km2). Its average depth is 21 feet (6.4 m), but it can be as deep as 174 feet (53 m). Two major bridges cross the Bay: the Chesapeake Bay Bridge in Maryland and the Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel in Virginia.

The Bay is famous for its beauty and its many resources. However, since the mid-1900s, there have been fewer crabs, oysters, and watermen (fishermen). Nutrient pollution and urban runoff (water flowing from cities) have harmed the water quality. This hurts the Bay's ecosystems and adds to the decline of shellfish because of too much fishing. Efforts to restore the Bay began in the 1990s and are still happening. These efforts are helping the native oyster population grow. The Bay's health improved in 2015 and showed slight improvements in 2021. The Bay also faces challenges from climate change, which causes sea level rise. This rise can erode coastlines and change the marine ecosystem.

Contents

- What Does "Chesapeake" Mean?

- How Was the Chesapeake Bay Formed?

- What Animals and Plants Live in the Chesapeake Bay?

- A Look Back: History of the Chesapeake Bay

- How People Use the Chesapeake Bay Today

- Chesapeake Bay Food

- What Environmental Problems Does the Bay Face?

- Exploring Under the Water: Underwater Archaeology

- Publications About the Bay

- The Chesapeake Bay in Pop Culture

- See also

- Images for kids

What Does "Chesapeake" Mean?

The word Chesepiooc comes from the Algonquian people. It means a village "at a big river." This name is one of the oldest English place-names still used in the United States. It was first used around 1585 or 1586 by explorers. The name might also refer to the Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe. They lived in the area now known as South Hampton Roads in Virginia. Some experts once thought "Chesapeake" meant "great shellfish bay," but this is not true. It likely meant "great water" or referred to a village at the Bay's mouth.

How Was the Chesapeake Bay Formed?

The Bay's Unique Geology

The Chesapeake Bay is an estuary that connects to the North Atlantic Ocean. It lies between the Delmarva Peninsula and the main part of North America. The Bay is a ria, which means it's a river valley that was flooded by the sea. It was once the Susquehanna River's floodplain when sea levels were lower. It is not a fjord, because large glaciers never reached this far south.

The Bay's shape and location were created by a huge space rock hitting Earth about 35.5 million years ago. This created the Chesapeake Bay impact crater. Much later, about 10,000 years ago, sea levels rose after the last ice age. This flooded the Susquehanna River valley, forming the Bay we see today.

Parts of the Bay, especially the Calvert County, Maryland, coastline, have cliffs called Calvert Cliffs. These cliffs are famous for their fossils, especially shark teeth. You can often find these fossils washed up on the beaches.

How Deep is the Chesapeake Bay?

Much of the Bay is shallow. Where the Susquehanna River flows in, the average depth is about 30 feet (9 m). Southeast of Havre de Grace, Maryland, it's about 10 feet (3 m) deep. Just north of Annapolis, it's about 35 feet (11 m) deep. The average depth of the entire Bay, including its smaller rivers, is 21 feet (6.4 m). Over 24 percent of the Bay is less than 6 ft (2 m) deep.

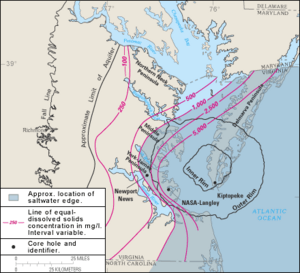

What Kind of Water is in the Bay?

Because the Bay is an estuary, it has fresh water, salt water, and brackish water. Brackish water is a mix of fresh and salt water. It has different saltiness zones:

- The freshwater zone is from the Susquehanna River to north Baltimore.

- The oligohaline zone has very little salt (0.5 to 10 parts per thousand). Freshwater animals can live here. It runs from north Baltimore to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge.

- The mesohaline zone has a medium amount of salt (1.07% to 1.8%). It runs from the Bay Bridge to the mouth of the Rappahannock River.

- The polyhaline zone is the saltiest (1.87% to 3.6%). Some of its water is as salty as the ocean. It runs from the Rappahannock River to the mouth of the Bay.

The climate around the Bay is mostly humid subtropical. This means hot, humid summers and cold to mild winters. The very northern part of the Bay, near the Susquehanna River, can freeze in winter. It is rare for the entire surface of the Bay to freeze.

Major Rivers Flowing into the Bay

The Chesapeake Bay receives water from over 150 rivers and streams. The largest rivers that flow directly into the Bay are:

- Susquehanna River

- Potomac River

- James River

- Rappahannock River

- York River

- Patuxent River

- Choptank River

What Animals and Plants Live in the Chesapeake Bay?

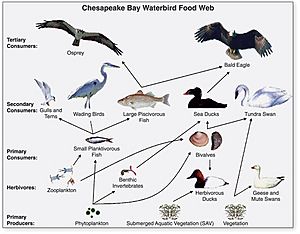

The Chesapeake Bay is home to many animals. Some live there all year, while others visit during certain seasons. There are over 300 types of fish and many kinds of shellfish and crabs. These include the Atlantic menhaden, striped bass, American eel, eastern oyster, Atlantic horseshoe crab, and the blue crab.

Many birds also live or visit here, such as ospreys, great blue herons, bald eagles, and peregrine falcons. The numbers of bald eagles and peregrine falcons have grown in recent years after being threatened by a chemical called DDT. The piping plover, a nearly threatened bird, also lives in the Bay's wetlands.

Larger fish like Atlantic sturgeon, different types of sharks, and stingrays visit the Bay. The Chesapeake Bay is an important nursery area for sharks on the East Coast. Even very large animals like bull sharks, tiger sharks, scalloped hammerhead sharks, basking sharks, and manta rays have been seen here. Smaller sharks and stingrays like the smooth dogfish, spiny dogfish, cownose ray, and bonnethead are also common.

Bottlenose dolphins live in the Bay during certain seasons or all year. There have been sightings of humpback whales. Even endangered North Atlantic right whales, fin, minke, and sei whales have been seen near the Bay.

A male manatee nicknamed "Chessie" visited the Bay many times between 1994 and 2011. This was unusual because the Bay is north of where manatees usually live. Other manatees are sometimes seen eating sea grasses in the Bay. Loggerhead turtles also visit the Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay also has many different plants, both on land and in the water. Common underwater plants include eelgrass and widgeon grass. These grasses provide food and homes for animals, add oxygen to the water, and help keep the water clear. Other plants around the Bay include wild rice, trees like red maple, loblolly pine, and bald cypress, and grasses like spartina and phragmites.

Some invasive plants have spread in the Bay. For example, Brazilian waterweed can grow very thick and harm the Bay's natural environment. Many local schools help by growing native Bay grasses and planting them in the water.

A Look Back: History of the Chesapeake Bay

Early Human Life Around the Bay

Humans have lived around the Chesapeake Bay for over 11,500 years. The first people, called "Paleoindians," were nomadic hunters. Later, Native American groups lived in villages near the water. They fished, farmed, and gathered shellfish. They grew crops like beans, corn, tobacco, and squash. Men hunted, and women managed the farming. Everyone helped with fishing and gathering shellfish. Over time, groups like the Powhatan, Piscataway, and Nanticoke formed larger groups called confederations, led by a central chief.

European Explorers Arrive

In 1524, Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed past the Chesapeake but did not enter. In 1525, Spanish explorer Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón sent an expedition that reached the Bay's mouth. The Spanish called it "Bahía de Santa María" (Bay of St. Mary). In 1570, Spanish Jesuits started a short-lived mission called Ajacán Mission on a Bay river in Virginia.

English colonists, like those sent by Sir Walter Raleigh, first saw the Bay's entrance in the late 1500s. In 1607, Europeans entered the Bay again. Captain John Smith of England explored and mapped the Bay between 1607 and 1609. He published "A Map of Virginia" in 1612. Smith wrote that "Heaven and earth have never agreed better to frame a place for man's habitation." The Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail now follows his historic journey. Many English people moved to the Chesapeake Bay area between 1640 and 1675, settling in the new colonies of Virginia and Maryland.

The Bay in American Wars

The Chesapeake Bay was important during the American Revolutionary War. In 1781, the Battle of the Chesapeake took place here. The French fleet defeated the British navy, which helped General George Washington and his French allies trap the British army at the Battle of Yorktown in Virginia. This battle led to the end of the war. The route they marched is now the Washington–Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail.

The Bay also saw conflict during the War of 1812. In 1813, British naval forces raided towns along the Bay. The Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, a fleet of American barges, tried to stop them. After months of fighting, the British landed and marched to burn the U.S. Capitol in August 1814.

Later, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, there were "Oyster Wars" over oyster harvesting. Until the mid-1900s, oyster fishing was a huge industry. Fishermen, called watermen, used special boats like skipjacks. Today, fewer watermen work on the Bay.

In the 1960s, the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant began using Bay water to cool its reactor.

How People Use the Chesapeake Bay Today

Boating and Shipping

The Chesapeake Bay is part of the Intracoastal Waterway. This waterway connects bays and inlets along the Atlantic coast. It links the Bay to the Delaware River through the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal. To the south, it links the Bay to North Carolina through the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal.

A busy shipping channel runs the length of the Bay. This channel is important for large ships going to or from the Port of Baltimore. It also connects to ports in Wilmington and Philadelphia on the Delaware River.

In the past, passenger steamships and packet boats used to travel the Bay. They connected different cities along its shores.

In the later 1900s, new road crossings were built. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge in Maryland connects Annapolis to Kent Island. A second bridge was added in 1973. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel in Virginia is about 20 miles (32 km) long. It connects Virginia's Eastern Shore to its mainland. This structure has bridges and two long tunnels that allow ships to pass freely. It opened in 1964.

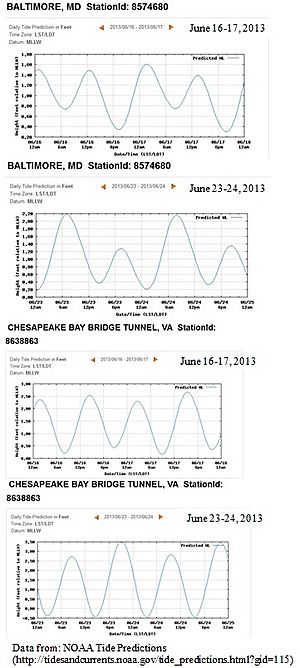

Tides in the Bay

The tides in the Chesapeake Bay are interesting and unique. This is because of the Bay's shape, wind patterns, and how it interacts with ocean tides.

At the Chesapeake Bay Bridge–Tunnel (CBBT), where the Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean, there are two high tides and two low tides each day. This is called a semi-diurnal tide. The ocean tides cause this.

In Baltimore, at the northern part of the Bay, the tides are different. They are a "mixed" tide, meaning the two high tides and two low tides each day are not always the same height. This happens because of the Bay's shape and how it affects the water's movement.

Fishing and Seafood

The Bay is famous for its seafood, especially blue crabs, clams, and oysters. In the mid-1900s, about 9,000 full-time watermen worked on the Bay. Today, there are fewer seafood resources. This is due to runoff from cities and farms, too much fishing, and foreign species.

The many oysters once led to the creation of the skipjack. This is Maryland's state boat, and it's the only working boat type in the U.S. still powered by sails. Other traditional Bay boats include the log canoe and the Chesapeake Bay deadrise.

Besides catching wild oysters, oyster farming is growing. Oyster farms are good for the environment because the Bay provides all the food the oysters need. Oysters also help filter extra nutrients from the water, which helps reduce eutrophication (too much algae). The Chesapeake Bay Program supports oyster restoration to help clean the Bay.

The Bay is also known for its rockfish, which is another name for striped bass. These fish were almost gone, but now their numbers have grown a lot. This happened because of laws that stopped rockfishing for a while. Now, rockfish can be caught in small, controlled amounts.

Other popular fish to catch in the Bay include shad, cobia, croaker, redfish, and flounder. Recently, non-native blue catfish have spread in rivers like the James River.

Tourism and Fun Activities

The Chesapeake Bay is a major attraction for tourists in Maryland and Virginia. People love to go fishing, crabbing, swimming, boating, kayaking, and sailing on the Bay. Tourism is very important for Maryland's economy. Many people find Annapolis a great place for families and water sports.

The Bay attracts many people who love the water. They enjoy boating, eating blue crabs, and learning about the local watermen. These watermen are crabbers and oystermen who have a unique way of life.

The Bay also plays a big role in the economies of Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania through nature-based recreation. Activities like wildlife watching, boating, and ecotourism depend on clean water. In 2006, people spent hundreds of millions of dollars on wildlife watching in these states, showing how important the Bay is.

Chesapeake Bay Food

In the past, people living around the Bay used simple cooking methods. They made one-pot meals like ham and potato casserole or stews with oysters, chicken, or venison. When John Smith arrived in 1608, he wrote that there were so many fish, they tried to catch them with frying pans!

Local foods included terrapins, smoked hams, blue crab, shellfish, local fish, and waterfowl. Blue crab is still a very popular food from the Bay today.

What Environmental Problems Does the Bay Face?

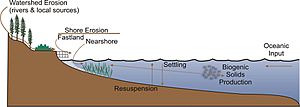

Pollution in the Bay

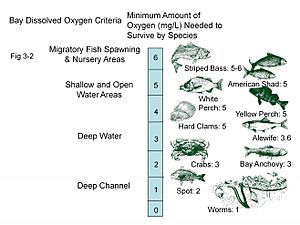

In the 1970s, scientists found "marine dead zones" in the Chesapeake Bay. These are areas where the water has so little oxygen that animals cannot live there. This caused many fish to die. In 2010, it was estimated that these dead zones killed 75,000 tons of clams and worms each year. This harms the Bay's food chain and reduces food for blue crabs. Sometimes, crabs even come onto shore to escape the low-oxygen water. This is called a "crab jubilee."

Low oxygen levels, called hypoxia, happen partly because of large algal blooms. These blooms grow from pollution that runs off from homes, farms, and factories. For example, a 2010 report criticized some farms for not properly managing animal waste, which then washed into the Bay's rivers.

The pollution has two main parts that cause algal blooms: phosphorus and nitrogen. These nutrients make algae grow too much. When alive, the algae block sunlight from reaching the bottom of the Bay. When they die and rot, they use up the oxygen in the water. Soil erosion and sediment runoff also block sunlight. This loss of underwater plants reduces homes for Bay animals. Beds of eelgrass have shrunk by more than half since the 1970s. Too much fishing, pollution, and diseases have also harmed the Bay's bottom.

The main sources of nutrient pollution are runoff from farms and from cities and suburbs. About half of the pollution comes from animal waste. Lawn fertilizers and air pollution from cars and power plants also add to the problem.

A harmful type of algae called Pfiesteria piscicida can affect fish and humans. In the late 1990s, this algae caused fish to die and gave swimmers rashes. Pollution from chicken farms was blamed for its growth.

Fewer Oysters in the Bay

The Bay's water is perfect for oysters, and oyster fishing was once very important. However, the oyster population has been greatly reduced in the last 50 years. Maryland once had about 200,000 acres (810 km2) of oyster reefs. By 2008, there were only about 36,000 acres (150 km2). It's thought that before Europeans arrived, oysters could filter all the Bay's water in about 3.3 days. By 1988, it took 325 days.

The biggest problem is too much fishing. Also, the large increase in human population has led to more pollution flowing into the Bay. Oyster diseases like MSX and Dermo have also hurt the population.

The decline of oysters has seriously harmed the Bay's water quality. Oysters naturally filter the water. With fewer oysters, the water has become very cloudy.

Efforts to Clean Up the Bay

Many groups are working to restore the Chesapeake Bay. These include federal, state, and local governments, the Chesapeake Bay Program, and environmental groups. The results have been mixed. One challenge is that much of the pollution comes from far upstream in states like New York and Pennsylvania.

In 2000, the Chesapeake Bay Program created Chesapeake 2000. This plan aimed to guide restoration activities until 2010. One part of this plan was to upgrade sewage treatment plants. By 2016, these upgrades had greatly reduced nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, even with more people living in the area.

Scientists have also worked to restore the native oyster population. Groups like the Oyster Recovery Partnership have placed millions of oysters in sanctuaries. Scientists believe that experimental oyster reefs created in 2004 now hold 180 million native oysters.

Rules to Reduce Pollution

In 2009, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) sued the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). They wanted the EPA to set strict limits on pollution entering the Bay. These limits, called a total maximum daily load (TMDL), would control pollution from farms, development, power plants, and sewage plants. The EPA agreed and set these limits in 2010. This was the largest and most complex TMDL the EPA had ever made. Even though some industries challenged it, the courts supported the EPA's plan.

In 2020, the CBF sued the EPA again. They wanted the EPA to make sure New York and Pennsylvania met their pollution reduction goals.

The EPA's 2010 plan requires all states in the Bay area to create detailed plans to reduce pollution. These plans include goals for water quality improvements. They involve upgrading pollution controls and using "best management practices" (BMPs). BMPs help control pollution from nonpoint sources, like farms and urban runoff. For example, farmers might plant trees along stream banks to reduce runoff. Developers might build stormwater management facilities to prevent pollution from construction.

In 2011, Maryland and Virginia passed laws to reduce pollution from lawn fertilizers. These laws limit the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus in fertilizers.

Is the Water Quality Getting Better?

In 2010, the Bay's health improved slightly, getting a rating of 31 out of 100, up from 28 in 2008. In 2016, a report from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES) said the Bay's health improved in 2015. In 2021, UMCES scientists reported slight improvements in water quality compared to 2020. The lower Bay areas showed the most improvement. Positive signs included lower nitrogen levels and more dissolved oxygen.

However, as of 2022, the CBF reported mixed results. Levels of toxic pollutants, nitrogen, and dissolved oxygen showed no improvement. Water clarity also slightly decreased. While oyster and rockfish populations have improved, blue crab populations continue to decline.

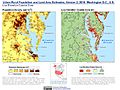

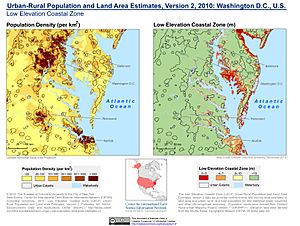

How Climate Change Affects the Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is already feeling the effects of climate change. One major effect is sea level rise. Water levels in the Bay have already risen one foot. They are predicted to rise another 1.3 to 5.2 feet in the next 100 years. This causes changes in marine ecosystems, destroys coastal marshes, and brings saltwater into fresh or brackish areas. Sea level rise also makes coastal flooding worse and increases runoff from upstream.

With more flooding and sea level rise, the Bay's 11,600 miles of coastline are at risk. This includes historic buildings and modern structures. Islands like Holland Island have already disappeared due to rising sea levels.

Other climate change effects, like ocean acidification and warmer temperatures, also stress marine life. These changes can lead to less dissolved oxygen and more acidic waters. This makes it harder for shellfish to build their shells. It also changes seasonal cycles important for breeding. Warmer temperatures can also mean that harmful germs stay active longer in the ecosystem.

Climate change might make low-oxygen areas (hypoxia) worse. However, reducing nutrient pollution would help much more than just stopping climate change. Warmer water holds less oxygen. So, as the Bay warms, low-oxygen periods might last longer each summer.

Programs in Maryland and Virginia are working to address climate change in the Chesapeake Bay. Important places like the port of Norfolk and the fishing industries will be directly affected by these changes.

Studying the Bay: Scientific Research

Researchers study the Chesapeake Bay to learn about water quality, plant and animal populations, shoreline erosion, tides, and harmful algal blooms. For example, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science checks the amount of underwater plants each summer. Many groups have ongoing monitoring programs. They use instruments on buoys and docks to record things like temperature, salinity, oxygen, and water clarity over time.

Some organizations that collect data in the Chesapeake Bay include:

- Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Maryland

- Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Virginia

- Chesapeake Bay Program

- Maryland Department of Natural Resources

- NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office

- Smithsonian Environmental Research Center

- United States Geological Survey

- University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science

- Virginia Institute of Marine Science

Exploring Under the Water: Underwater Archaeology

Underwater archaeology is a field that explores old sites hidden under water. In 1988, the Maryland Maritime Archeology Program (MMAP) was created. Its goal is to manage and explore underwater sites in the Chesapeake Bay. This happened after a law in 1987 gave states ownership of important shipwrecks.

Water covers 25% of Maryland. There are over 550 underwater archaeological sites in the Bay and its rivers. These sites range from 12,000-year-old Native American villages to shipwrecks from World War II. Susan Langley has been Maryland's State Underwater Archaeologist since 1995. She has greatly improved the MMAP's technology, allowing more sites to be explored.

Finding and Studying Underwater Sites

The Chesapeake Bay has been affected by natural forces like erosion and storms, and by human activities like pollution and construction. These make it hard to find underwater sites. The MMAP uses special equipment like marine magnetometers (to find iron) and side-scan sonar (to find objects on the seafloor). They also use precise GPS.

Once a site is found, the team carefully works to preserve it. Remains from shipwrecks are very fragile after being in saltwater for centuries. They take photos and videos, create maps, and build models. This helps them learn about the people who built the ships and lived in the area. The MMAP shares its findings but keeps the exact locations secret to prevent looting.

Important Underwater Discoveries

There are over 1,800 ship and boat wrecks in the Chesapeake Bay and its waterways. Many ancient canoes and artifacts have been found, giving clues about Native American life. In 2014, archaeologists found the skull of a prehistoric mastodon, which was 22,000 years old. A carved stone blade was also found nearby, which might be at least 14,000 years old. This discovery has led to new ideas about the first people in North America.

The Chesapeake Bay Flotilla was a fleet of American ships used in the War of 1812. Many of these ships were burned and sunk. Since 1978, many artifacts like weapons and personal items have been found from these wrecks.

In 1774, a British ship called Peggy Stewart arrived in Annapolis with tea. The colonists refused to pay a new tea tax, so they burned and sank the ship. This site is now important for underwater archaeologists. In 1949, a German submarine, U-1105, was sunk in the Potomac River after being studied by the U.S. Navy. It is now a popular site for underwater archaeologists.

Virginia also has an underwater archaeology program. In 1982, they explored a fleet of British battleships sunk in the York River during the Revolutionary War. Over 5,000 items were found from one ship called Betsy.

Publications About the Bay

Several magazines and publications cover topics about the Chesapeake Bay:

- The Bay Journal shares environmental news for the Bay area.

- Bay Weekly is an independent newspaper for the region.

- The Capital newspaper covers news in Annapolis and Maryland's Western Shore.

- Chesapeake Bay Magazine and PropTalk focus on powerboating.

- SpinSheet focuses on sailing.

- What's Up Magazine is a free monthly publication about Annapolis and the Eastern Shore.

The Chesapeake Bay in Pop Culture

In Books

- Beautiful Swimmers: Watermen, Crabs and the Chesapeake Bay (1976) by William W. Warner is a non-fiction book about the Bay, blue crabs, and watermen.

- Chesapeake (1978) is a novel by James A. Michener.

- Chesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier Island (2018) by Earl Swift is a non-fiction book about the crabbing community on Tangier Island.

- Dicey's Song (1983) and other books in Cynthia Voigt's Tillerman series are set in Crisfield on the Bay.

- Jacob Have I Loved (1980) by Katherine Paterson is a novel about two sisters growing up on a Bay island.

- Patriot Games (1987) and Without Remorse (1993) by Tom Clancy feature characters living near or on the Bay.

- Red Kayak (2004) by Priscilla Cummings shows conflicts between watermen and wealthy newcomers.

- Sabbatical: A Romance (1982) and The Tidewater Tales (1987) by John Barth are novels set around the Bay.

- The Oyster Wars of Chesapeake Bay (1997) by John Wennersten is about the historic Oyster Wars.

In Movies

- The Bay (2012) is a horror movie about pollution from chicken farms affecting the Bay.

- Expedition Chesapeake, A Journey of Discovery (2019) stars Jeff Corwin and explores the Bay.

In TV Shows

- In Chesapeake Shores, the O'Brien family lives in a small town near Baltimore on the Bay.

- MeatEater by Steven Rinella, Season 8, Episode 3-4 "Ghosts of the Chesapeake" features the Bay's eastern shore.

Other Media

- Singer and songwriter Tom Wisner, known as the Bard of the Chesapeake Bay, recorded albums about the Bay.

- The Chesapeake Bay is mentioned in the musical Hamilton, in the song "Yorktown (The World Turned Upside Down)". It describes the Battle of Yorktown, where the French fleet was waiting in Chesapeake Bay.

See also

In Spanish: Bahía de Chesapeake para niños

In Spanish: Bahía de Chesapeake para niños

- Chesapeake Bay Interpretive Buoy System

- Chesapeake Bay Retriever

- Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation

- Great Ireland

- National Estuarine Research Reserve

- Old Bay Seasoning

Images for kids

-

Boundaries of the Chesapeake Bay impact crater.

-

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge, near Annapolis, Maryland

-

Food chain diagram for waterbirds of the Chesapeake Bay

-

Revised map of John White's original by Theodore DeBry. In this 1590 version, the Chesapeake Bay appears named for the first time.

-

Oyster boats at war off the Maryland shore (1886 wood engraving). Regulation of the oyster beds in Virginia and Maryland has existed since the 19th century.

-

Lighthouses and lightships such as Chesapeake have helped guide ships into the Bay.

-

A skipjack, part of the oystering fleet in Maryland

-

The Thomas Point Shoal Light in Maryland

-

Tidal wetlands of the Chesapeake Bay

-

Dissolved oxygen levels (Milligrams per liter) required by various marine animals living in the Chesapeake Bay.

-

Population density and elevation above sea level around the Chesapeake Bay. The Chesapeake Bay is especially vulnerable to sea level rise.

-

Chesapeake Bay Interpretive Buoy System smart buoy on the Patapsco River.

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |