Fossil facts for kids

A fossil is the remains or a sign of an ancient living thing. Fossils tell us about life from millions of years ago.

You can find fossils of animals, plants, or tiny protists. They are usually found in sedimentary rock. This type of rock forms from layers of sand, mud, and other materials that build up over time.

Most fossils keep the shape of the original living thing. However, the original parts of the body are replaced by hard, inorganic materials. These materials can be things like calcium carbonate (which is in shells) or silica (which is in sand). So, a fossil feels and is made of rock. It has been "turned into rock," a process called petrification or mineralization.

Sometimes, a fossil is not the actual body. It can be an imprint or impression left in ancient mud. This mud later turned into rock.

Some organisms turn into fossils easily, while others do not. The most common fossils come from creatures with hard parts. For example, the hard, calcitic shells of molluscs (like clams and snails) and brachiopods are very common. These sea creatures have created many fossil-rich layers of limestone in the Earth.

Soft-bodied organisms can also become fossils, but only in very special conditions. The Ediacaran biota are a good example of soft-bodied fossils.

The most famous fossils are often those of giant, prehistoric dinosaurs. You can see their fossilized bones and tracks in many museums.

The study of fossils is called paleontology. Geologists and biologists are the scientists who study them. If they study how ancient living things fit into their environment, it is called paleobiology.

Contents

Where Are Special Fossils Found?

There are some places where fossils are found with amazing details. Or, they might be found in very large numbers. Scientists call these special sites Lagerstätten. This is a German word.

One famous example is the La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles. Another is the Solnhofen limestone quarries in Bavaria, Germany. These places give us a lot of information about ancient life.

Different Kinds of Fossils

Fossils can be different sizes and types.

Microfossils and Macrofossils

- Microscopic or very tiny fossils are called "microfossils." You need a microscope to see them.

- Larger, macroscopic fossils are called "macrofossils." These are things you can see with your eyes, like seashells or mammal bones.

Pseudofossils

Some stones look like fossilized organisms but are not fossils at all. These are called "pseudofossils." They are natural rock formations that just happen to look like living things.

Trace Fossils and Other Signs

Even without the actual body, there can be indirect signs of prehistoric life. These are called trace fossils.

- Examples include a worm's trail or an animal's footprint. These are quite common.

- Fossilized excrement (poop) is known as a coprolite.

- Chemical traces of ancient organisms are called chemofossils.

- Objects made by prehistoric people are called artifacts. These are not fossils, but they also tell us about the past.

Sometimes, even soft-bodied animals can leave permanent impressions or carbon traces. This happens in special cases, giving us fossils of small, soft creatures.

Other Ways Fossils Form

Fossils can also form in other ways, not just by turning into rock.

- Sometimes, dryness (desiccation), freezing, or pine resin can preserve living things.

- Examples include mummified animals, ice-covered wooly mammoths, and insects trapped in amber.

Living Fossils

Living fossils are not fossils in the traditional sense. They are modern-day organisms that look very similar to their ancient ancestors from millions of years ago. They have changed very little over time. Good examples are the ginkgo tree, the coelacanth fish, and the horseshoe crab.

How Were Fossils First Understood?

Many people in ancient times noticed fossils. But not everyone understood that they were the remains of living things.

One of the first to write about his ideas was the Ancient Greek philosopher Xenophanes (around 570–470 BC). Other writers reported his thoughts: He noticed that shells were found on land and mountains. He saw impressions of fish and seaweed in quarries. He thought these were formed when everything was covered in mud long ago, and the impressions dried in the mud.

These ideas were rediscovered in Europe in the 1600s. Scientists like Nicolas Steno in the Netherlands and Robert Hooke in London wrote and lectured about fossils. In the 1700s, people started collecting fossils, and serious thinking about geology began. By the 1800s, geology became a modern science. Fossils played a big part in understanding the theory of evolution.

Related pages

- Extinction

- Evolution

- Palaeontology

- Earth history

- List of extinction events

- Age of the Earth

- Lagerstätte

Images for kids

-

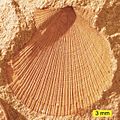

External mold of a bivalve from the Logan Formation, Lower Carboniferous, Ohio

-

Recrystallized scleractinian coral (aragonite to calcite) from the Jurassic of southern Israel

-

The wasp Leptofoenus pittfieldae trapped in Dominican amber, from 20 to 16 million years ago. It is known only from this specimen.

-

Eroded Jurassic plesiosaur vertebral centrum found in the Lower Cretaceous Faringdon Sponge Gravels in Faringdon, England. An example of a remanié fossil.

-

A subfossil dodo skeleton

-

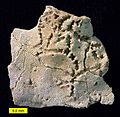

An example of a pseudofossil: Manganese dendrites on a limestone bedding plane from Solnhofen, Germany; scale in mm

-

Fossil shells from the cretaceous era sea urchin, Micraster, were used in medieval times as both shepherd's crowns to protect houses, and as painted fairy loaves by bakers to bring luck to their bread-making.

-

Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus from the 1834 Czech edition of Cuvier's Discours sur les revolutions de la surface du globe

-

Phacopid trilobite Eldredgeops rana crassituberculata. The genus is named after Niles Eldredge.

-

Carbonized fossil of a possible leech from the Silurian Waukesha Biota of Wisconsin.

-

Cambrian trace fossils including Rusophycus, made by a trilobite

-

A coprolite of a carnivorous dinosaur found in southwestern Saskatchewan

-

Densely packed, subaerial or nearshore trackways (Climactichnites wilsoni) made by a putative, slug-like mollusk on a Cambrian tidal flat

-

Eocene fossil fish Priscacara liops from the Green River Formation of Wyoming

-

Megalodon and Carcharodontosaurus teeth. The latter was found in the Sahara Desert.

-

Fossil shrimp (Cretaceous)

-

Petrified wood in Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

-

Petrified cone of Araucaria mirabilis from Patagonia, Argentina dating from the Jurassic Period (approx. 210 Ma)

-

Silurian Orthoceras fossil

-

Micraster echinoid fossil from England

-

Productid brachiopod ventral valve; Roadian, Guadalupian (Middle Permian); Glass Mountains, Texas.

-

Fossils from beaches of the Baltic Sea island of Gotland, placed on paper with 7 mm (0.28 inch) squares

-

Dinosaur footprints from Torotoro National Park in Bolivia.

See also

In Spanish: Fósil para niños

In Spanish: Fósil para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |