Bivalve facts for kids

Quick facts for kids BivalvesTemporal range: Cambrian – Recent

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Mussels in the intertidal zone in Cornwall, England | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: |

Bivalvia

Linnaeus, 1758

|

Bivalves are a big group of molluscs, also known as pelecypods. Think of them as animals with two shells!

They have a hard shell made of two parts, called 'valves'. These shells are usually made of calcium carbonate, which is a strong, chalky material. The soft body of the bivalve stays safe inside these two shells. Often, their shells look the same on both sides, like a mirror image.

There are more than 30,000 different kinds of bivalves, including those that are now fossils. About 9,200 types are still alive today. Most bivalves live in the ocean or in brackish water (water that's a mix of fresh and salty). Some even live in fresh water. All bivalves are filter feeders. This means they get their food by filtering tiny bits of food from the water. Some are even carnivores, eating much larger prey than the tiny algae other bivalves eat.

Some of the most famous bivalves you might know are clams, mussels, scallops, and oysters.

Contents

What is a Bivalve Shell Like?

Bivalves have two shells, or valves, that are joined together by a special hinge. This hinge often has tiny "teeth" that help the shells fit together perfectly. The shells are made of a hard mineral like calcite or aragonite.

On the outside, the shells are covered by a layer called the periostracum. This is an organic, tough layer that gives the shell its color and protects it.

Strong muscles, called adductor muscles, usually keep the shells tightly shut. But some bivalves, like scallops, can use these muscles to quickly open and close their shells, which helps them swim!

How Do Bivalves Eat?

Bivalves are amazing at filtering food from the water. They take in water that has tiny bits of plankton and other food floating in it.

Many bivalves have special tubes called siphons. They usually have two siphons: one to suck water in and another to push water out.

When water comes into the bivalve through the "incurrent" siphon, any tiny food particles get caught in a sticky mucus on their gills. The food then moves to the bivalve's mouth. After digestion in its stomach and intestine, anything not digested leaves through the "excurrent" siphon with the water.

Siphons are super helpful for bivalves that burrow into the sediment (like mud or sand). Bivalves that live on top of the ground, like scallops and oysters, don't usually need siphons.

How Do Bivalves Move Around?

Bivalves have different ways to get around or stay safe.

Digging into the Ground

Many bivalves are great at digging into soft ground like mud or sand. They can move quickly through it. For example, razor shells can dig into the sand really fast to escape from enemies. Cockles are also good at digging.

Swimming Away from Danger

Some bivalves can actually swim! Scallops and file clams can clap their shells together to create a jet of water, which pushes them away from a predator. Cockles can use their strong foot to leap out of danger. However, these swimming and leaping methods use a lot of energy, so the animals get tired quickly.

Special Defenses of Bivalves

Some bivalves have unique ways to protect themselves. For instance, file shells can release a bad-smelling liquid when they feel threatened. Other bivalves, like fan shells, have a special organ that can produce acid!

Bivalves and Brachiopods: A Comparison

Bivalves might look a bit like another group of shelled animals called brachiopods, but they are actually quite different. In brachiopods, their two shells are on their top and bottom sides. But in bivalves, the two shells are on their left and right sides.

Bivalves first appeared a very long time ago during the Cambrian explosion. They became more common during the Palaeozoic Era and started to become more dominant than brachiopods during the Mesozoic Era.

After a huge event called the Permian–Triassic extinction event, which greatly affected many animals, bivalves grew rapidly in numbers and types. Brachiopods, however, lost most of their different kinds. This meant that bivalves took over the best places to live, especially near the shore. Today, brachiopods usually live in deeper waters where there isn't as much food.

Images for kids

-

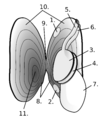

Drawing of freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) anatomy: 1: posterior adductor, 2: anterior adductor, 3: outer left gill demibranch, 4: inner left gill demibranch, 5: excurrent siphon, 6: incurrent siphon, 7: foot, 8: teeth, 9: hinge, 10: mantle, 11: umbo

-

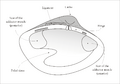

Interior of the left valve of a venerid

-

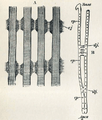

Four filaments of the gills of the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) a) part of four filaments showing ciliated interfilamentar junctions (cj) b) diagram of a single filament showing the two lamellae connected at intervals by interlamellar junctions (ilj) and the position of the ciliated interfilamentar junctions (cp)

-

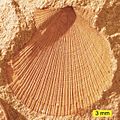

A fossil Jurassic brachiopod with the lophophore support intact

-

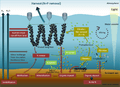

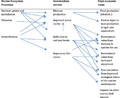

Nutrient extraction services provided by bivalves. Blue mussels are used as examples but other bivalves like oysters can also provide these nutrient extraction services.

-

Carved nacre in a 16th-century altarpiece

-

Mussels in the intertidal zone in Cornwall, England

-

Aviculopecten subcardiformis; a fossil of an extinct scallop from the Logan Formation of Wooster, Ohio (external mold)

See also

In Spanish: Bivalvos para niños

In Spanish: Bivalvos para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |