Dodo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids DodoTemporal range: late Holocene

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

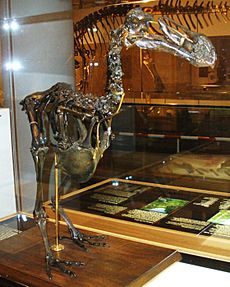

| Dodo reconstruction at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History |

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: |

Raphus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Raphus cucullatus (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

|

|

| Former range (in red) | |

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was a type of flightless bird that is now extinct. Like many other birds living on islands, dodos did not need to fly because there were no large predators where they lived. Dodos were related to pigeons and lived only on the island of Mauritius. The dodo is one of the first animal species known to have disappeared because of humans. Dodos have been extinct since the late 1600s.

Contents

What Does the Name 'Dodo' Mean?

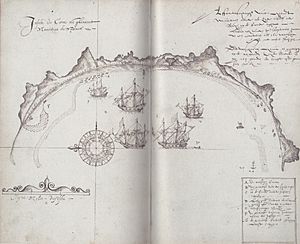

The exact meaning of the word 'dodo' is not fully clear. A Dutch captain named Wybrand van Warwijck found the island and the bird in 1598. He called the bird 'walgvogel', which means "disgusting bird." This was because its meat was not pleasant to eat. Four years later, another Dutch captain, Willem van Westsanen, used the word 'Dodo' for the first time.

Some dictionaries suggest that "dodo" comes from the Portuguese word doido, meaning "fool" or "crazy." Another idea is that 'dodo' was a sound that copied the bird's own call, which was a two-note sound like a pigeon's "doo-doo."

What Did the Dodo Look Like?

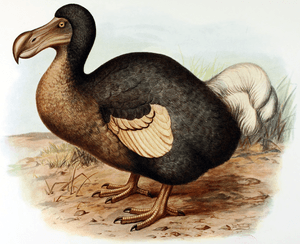

Since no complete dodo bodies exist today, it is hard to know exactly what they looked like, including their feathers and colors. We mostly rely on drawings and written stories from people who saw dodos between 1598 and 1662. Most pictures show the dodo with grayish or brownish feathers. It had lighter feathers on its wings and a tuft of curly light feathers on its rear end. Its head was gray and bare, and its beak was green, black, and yellow. Its legs were strong and yellowish, with black claws.

Dodos were very large birds, standing up to 1 meter (about 3 feet) tall. Male dodos were bigger and had longer beaks than females. Scientists have different ideas about how much dodos weighed. Some estimates say they weighed between 10.6 and 17.5 kilograms (23 to 38 pounds) in the wild. Some dodos kept by people might have been overfed and weighed more, up to 27.8 kilograms (61 pounds). It is also thought that their weight might have changed with the seasons, being fatter in cooler times.

The dodo's skull was very different from other pigeons. It was much stronger, and its beak had a hooked tip. The upper part of the beak was almost twice as long as the main part of the skull. The dodo's eyes were small and set far back on its head.

Dodo Bones and Body

The dodo had a strong neck, likely to support its heavy skull and beak. Its breastbone (sternum) was large but small compared to its body size, especially when compared to smaller pigeons that can fly. The bones in its wings and shoulders were smaller than those of flying pigeons. This shows that dodos had lost the ability to fly.

Many of the dodo's bone features that make it different from flying pigeons are because it could not fly. Its hip bones were thicker to support its heavy weight. Its small wings were underdeveloped, keeping features usually seen in young birds.

Old Drawings of Dodos

The travel journal of a Dutch ship called Gelderland (from 1601–1603) has the only known drawings of live or recently killed dodos made on Mauritius. It is not known how many of the other 17th-century dodo pictures were drawn from live birds or from stuffed ones. This affects how accurate they are.

After 1638, most dodo pictures seem to be based on earlier drawings. This was around the time that reports of dodos became less common. The traditional image of the dodo is a very fat and clumsy bird. However, scientists now believe this might be an exaggeration. Many old European pictures may have been based on dodos that were overfed in captivity or poorly stuffed after they died.

The Dutch painter Roelant Savery drew the most dodos. He made at least ten pictures. A famous painting of his from 1626, called Edwards's Dodo, is now in the Natural History Museum in London. This picture shows a very fat bird and has been used as a model for many other dodo drawings.

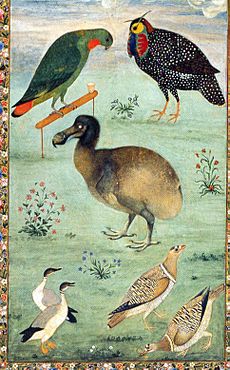

An Indian painting found in the 1950s shows a dodo with other Indian birds. This picture shows a thinner, brownish bird. Many experts believe it is one of the most accurate pictures of a living dodo. It is thought to be from the 1600s and was likely painted by Ustad Mansur. The bird in the painting probably lived in the zoo of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir.

Dodo Behavior and Environment

We do not know much about how dodos behaved because most old descriptions are very short. Studies of their leg bones suggest they could run quite fast. Their legs were strong to support their large bodies, making them quick and able to move well in the thick forests where they lived. Even though their wings were small, their bones show that they had strong muscles. They might have used their wings for showing off or for balance, just like some flying pigeons do.

The dodo probably used its large, hooked beak to fight over its territory. The island of Mauritius gets more rain and has less seasonal changes than Rodrigues, which would mean more food was available. This might have made the dodo less aggressive than its relative, the Rodrigues solitaire.

Where Dodos Lived

We do not know the dodo's favorite place to live. However, old descriptions suggest they lived in the drier forest areas along the coast of southern and western Mauritius. This idea is supported because most dodo bones have been found in the Mare aux Songes swamp, which is near the sea in southeastern Mauritius. Living in only a small part of the island might have made them more likely to become extinct.

Before humans arrived, Mauritius was completely covered in forests. Now, very little of these forests remain because of deforestation. The dodo lived alongside many other Mauritian birds that are now extinct, such as the flightless red rail and the broad-billed parrot.

What Dodos Ate

A Dutch document from 1631, which is now lost, is the only record of what dodos ate. It also said that they used their beak for defense. The document mentioned that dodos ate fruit.

Besides fallen fruits, dodos probably ate nuts, seeds, bulbs, and roots. Some scientists think they might have also eaten crabs and shellfish, like their relatives, the crowned pigeons. Dodos likely ate many different kinds of food, especially since captive dodos were given a variety of foods during long sea trips.

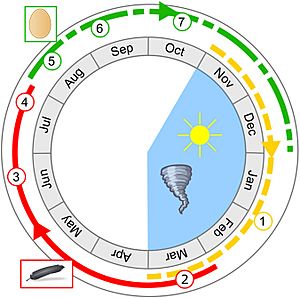

Mauritius has distinct dry and wet seasons. It is thought that dodos might have eaten a lot of ripe fruits at the end of the wet season to get fat. This fat would help them survive the dry season when food was scarce. Old reports describe the dodo as having a "greedy" appetite.

In 2016, scientists made the first 3D model of a dodo's brain. They found that the dodo had a very good sense of smell. This strong sense of smell might have helped them find fruit and small prey.

It is not known how young dodos were fed. However, related pigeons produce "crop milk" to feed their young. Dodos had a large crop, which was probably used to store food and make this milk.

In 1973, it was thought that the tambalacoque tree, also known as the dodo tree, was dying out on Mauritius. There were supposedly only 13 trees left, all about 300 years old. A scientist named Stanley Temple suggested that the tree needed the dodo to spread its seeds. He believed the seeds would only grow after passing through the dodo's digestive system. He claimed the tambalacoque was almost extinct because the dodo was gone. However, other experts have disagreed, saying that the tree's decline was exaggerated and that its seeds could grow without the dodo, though rarely. Other animals like tortoises or fruit bats might have also helped spread the seeds.

Dodo Life Cycle

A 2017 study looked at dodo bones and old records to learn about the dodo's life. The study suggested that dodos probably bred around August. They might have gotten fat before this time. The chicks grew very quickly, reaching almost adult size and being able to reproduce before the Austral summer or cyclone season. Adult dodos would then shed their old feathers (moult) after the Austral summer, around March. This moulting would finish by the end of July, just in time for the next breeding season. Different stages of moulting might explain why old descriptions of dodo feathers were not always the same.

Dodos and Humans

Dodos Sent Abroad

People found the dodo interesting enough that live ones were sent to Europe and the East. We do not know for sure how many dodos survived these long journeys. Based on old stories and paintings, at least eleven dodos were sent alive to other places.

The earliest known picture of a dodo in Europe is from around 1610. It is part of a collection of paintings of animals in the royal zoo of Emperor Rudolph II in Prague. This dodo might have been a young one, and it seems to have been dried or preserved. The fact that whole stuffed dodos were in Europe suggests they were brought alive and then died there.

One dodo was reportedly sent all the way to Nagasaki, Japan, in 1647. Documents from 2014 confirmed this story, showing that it arrived alive. It was a gift and was considered very valuable. This is the last recorded live dodo in captivity.

Why the Dodo Became Extinct

Like many animals that grew up without big predators, the dodo was not afraid of humans. This lack of fear and its inability to fly made the dodo easy for sailors to catch. While some reports mention large numbers of dodos being killed for ship food, archaeological digs have found little proof of widespread hunting by humans.

The human population on Mauritius was never more than 50 people in the 1600s. However, they brought other animals with them, such as dogs, pigs, cats, rats, and monkeys. These animals raided dodo nests and competed for the limited food. At the same time, humans destroyed the dodo's forest habitat. Today, scientists believe that the impact of these introduced animals, especially pigs and monkeys, was more harmful to the dodo population than human hunting.

Some people have suggested that the dodo might have already been rare or lived in only a few places before humans arrived. This is because it would be unlikely for them to become extinct so quickly if they lived all over the island. However, the dodo survived hundreds of years of volcanic activity and climate changes, showing it was strong within its natural environment.

There is some debate about the exact date of the dodo's extinction. The last widely accepted report of a dodo sighting is from 1662. A sailor named Volkert Evertsz described birds caught on a small island off Mauritius. He said:

These animals stared at us and stayed still, not knowing whether they had wings to fly away or legs to run off. They let us get as close as we wanted. Among these birds were those they call Dod-aersen (a kind of very big goose); these birds cannot fly, and instead of wings, they only have a few small pins, yet they can run very swiftly. We gathered them together so we could catch them with our hands, and when we held one by its leg, and it made a loud noise, the others all of a sudden came running as fast as they could to help it, and by which they were caught and made prisoners also.

The dodos on this small island might not have been the very last ones. The last claimed sighting of a dodo was reported in hunting records from 1688. Statistical analysis suggests a new estimated extinction date of 1693. However, some experts believe that later descriptions using the name "Dodo" might have actually been talking about the red rail, another bird. The IUCN Red List accepts the 1662 date as the last reliable observation. In any case, the dodo was likely extinct by 1700, about a century after it was first discovered in 1598.

Even though the dodo's rarity was known in the 1600s, its extinction was not fully understood until the 1800s. This was partly because, for religious reasons, people did not believe that species could become extinct. Also, many scientists doubted that the dodo had ever existed, thinking it was too strange to be real. The dodo was first used as an example of human-caused extinction in a magazine in 1833. Since then, it has become a symbol of extinction.

Dodo Remains Found

Old Specimens from the 1600s

The only dodo remains that still exist from the 1600s are:

- A dried head and foot at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

- A skull at the University of Copenhagen Zoological Museum.

- An upper jaw and leg bones at the National Museum, Prague.

Several stuffed dodos were mentioned in old museum lists, but none of them survived.

The Oxford head and foot are the only known soft tissue remains. They belonged to the last known stuffed dodo, which was first mentioned in 1656. Many sources say that the museum burned the stuffed dodo around 1755 because it was decaying badly, saving only the head and leg. However, it is now believed that the specimen was simply removed from display to protect what was left of it. This remaining soft tissue has continued to decay. Very few feathers are left on the head. This specimen is probably from a female dodo.

The Copenhagen skull is thought to be the oldest surviving dodo remains brought to Europe in the 1600s. It is smaller than the Oxford skull and may have belonged to a female.

Dodo Bones from the Ground

Until 1860, the only dodo remains known were the few incomplete specimens from the 1600s. In 1865, a schoolmaster named George Clark found many dodo bones in the Mare aux Songes swamp in Southern Mauritius. He had his workers wade through the swamp, feeling for bones with their feet. They found the remains of over 300 dodos.

Clark's reports about these finds renewed interest in the dodo. The swamp yielded many bones, but few skull and wing bones. This might be because the upper bodies were washed away or eaten by scavengers, while the lower bodies were stuck in the swamp.

In 2005, a part of the Mare aux Songes swamp was dug up again by an international team of researchers. They found many remains, including bones from at least 17 dodos of different ages. They also found several bones from one individual bird that were still in their natural position. These findings were announced in December 2005. Scientists believe that dodos and other animals got stuck in the Mare aux Songes while trying to find water during a long drought about 4,200 years ago.

Around 1900, an amateur naturalist named Louis Etienne Thirioux also found many dodo remains. These included the first complete skeleton of a single dodo, found in 1904 in a cave near Le Pouce mountain. This is the only known complete skeleton of an individual dodo. Thirioux gave this specimen to the Museum Desjardins (now the Natural History Museum at Mauritius Institute). In 2006, explorers found another complete skeleton of a dodo in a lava cave in Mauritius. This was only the second time a complete skeleton from one individual dodo had been found.

Today, 26 museums around the world have important dodo remains. Most of these bones were found in the Mare aux Songes swamp. Many museums have almost complete skeletons, put together from the bones of several different dodos.

The White Dodo

The idea of a "white dodo" from Réunion island is now thought to be a mistake. It was based on old reports of another bird called the Réunion ibis and 17th-century paintings of white, dodo-like birds. The confusion started when a Dutch visitor to Réunion around 1619 mentioned fat, flightless birds. Later, a white, stocky, and flightless bird was first mentioned as part of Réunion's animals in 1625.

When 17th-century paintings of white dodos were found in the 1800s, people thought they showed these Réunion birds. However, experts now believe that all pictures of white dodos were based on Roelant Savery's 1611 painting Landscape with Orpheus and the animals. This painting shows a whitish dodo, which was likely based on a stuffed specimen in Prague. Savery's later pictures all show grayish birds, perhaps because he had seen a different specimen by then. Some scientists think the painted specimen was white because of albinism (a lack of color). Others suggest it was a young bird, or that the old stuffed specimen had faded.

In 1987, scientists found fossils of a recently extinct species of ibis from Réunion. This ibis had a relatively short beak. Later, it was suggested that these fossils might be from the "Réunion solitaire" that people had described. This ibis is now known as Threskiornis solitarius. Birds of this type are white and black with slender beaks, which matches the old descriptions of the Réunion solitaire. No fossils of dodo-like birds have ever been found on Réunion island.

Images for kids

-

The Nicobar pigeon is the closest living relative of the dodo.

-

Labeled sketch from 1634 by Sir Thomas Herbert, showing a broad-billed parrot ("Cacato"), a red rail ("Hen"), and a dodo.

-

Illustration of Dutch sailors pursuing dodos, by Walter Paget, 1914. Hunting by humans is not believed to have been the main cause of the bird's extinction.

See also

In Spanish: Dodo para niños

In Spanish: Dodo para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |