Dutch East India Company facts for kids

|

|

Company flag (1630)

|

|

|

Native name

|

|

|---|---|

| Partially state-owned enterprise | |

| Industry | Proto-conglomerate |

| Fate | Dissolved and nationalised as Dutch East Indies |

| Predecessor |

Voorcompagnieën / Pre-companies (1594–1602)

|

| Founded | 20 March 1602, by a government-directed consolidation of the voorcompagnieën/pre-companies |

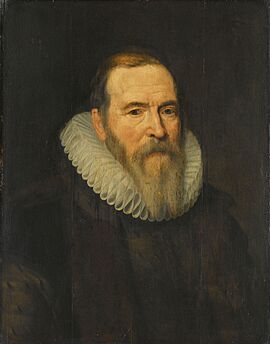

| Founder | Johan van Oldenbarnevelt and the States General |

| Defunct | 31 December 1799 |

| Headquarters |

|

|

Area served

|

|

|

Key people

|

|

| Products | Spices, silk, porcelain, metals, livestock, tea, grain, rice, soybeans, sugarcane, wine, coffee |

The Dutch East India Company, also known as the VOC (from its Dutch name, Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), was a very powerful trading company. It was one of the first companies where many people could buy shares, making it a "joint-stock company." The Dutch government created the VOC on March 20, 1602, by combining several smaller companies. It was given special permission, a "charter," to be the only Dutch company allowed to trade in Asia for 21 years. People in the Dutch Republic could buy and sell parts of the company, called shares, in places like the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. The VOC had amazing powers, almost like a government itself. It could start wars, make treaties, create its own money, and even set up new settlements. Because it traded in so many different places, it's often called the world's first "multinational corporation."

Statistically, the VOC was incredibly successful, far bigger than any other company trading in Asia. From 1602 to 1796, it sent almost a million Europeans on 4,785 ships to work in Asia. These ships brought back over 2.5 million tons of goods from Asia. The company also transported people for labor, which was a sad part of its history. To compare, all other European countries together sent fewer people to Asia during a similar time. The British East India Company, its closest rival, used far fewer ships and carried much less cargo. The VOC made enormous profits, especially from its control over the spice trade in the 1600s.

The VOC started in 1602 to make money from the valuable spices found in the Maluku Islands. In 1619, it set up its main base in the port city of Jayakarta, which it renamed Batavia (now Jakarta). For the next two centuries, the company gained more ports and land to protect its trade. It was a very important company, paying good profits to its shareholders for nearly 200 years. However, by the late 1700s, problems like illegal trading, corruption, and high costs led the company into trouble. The VOC went bankrupt and officially closed down in 1799. The Dutch government then took over all its lands and debts.

Contents

The VOC: Name, Logo, and Flag

In Dutch, the company's full name was Vereenigde Nederlandsche Geoctroyeerde Oostindische Compagnie. This means 'United Dutch Chartered East India Company'. It was shortened to VOC. The company's famous logo was a big letter 'V' with an 'O' on one side and a 'C' on the other. Many people think this was the world's first widely recognized company logo. You could see it on flags, cannons, and even coins.

Sometimes, the first letter of the city where a VOC office was located was added to the top of the logo. The logo was well-designed, simple, and easy to recognize. This helped the company stand out when most businesses didn't think about a "corporate identity." Even today, an Australian wine maker uses the VOC logo, having registered the old company's name.

Many people, especially in English-speaking countries, call it the 'Dutch East India Company'. This helps tell it apart from other similar companies, like the British East India Company or the French East India Company. Other names for the VOC included 'United East India Company' or 'Jan Company'.

The Story of the Dutch East India Company

How the VOC Began its Journey

Before the Dutch Revolt started around 1566, the city of Antwerp was a major trading hub in northern Europe. Later, Portuguese traders worked with powerful German, Spanish, and Italian families. They used Hamburg as a main port, which meant Dutch merchants were left out of the spice trade. Also, the Portuguese couldn't bring enough spices, especially pepper, to meet everyone's needs. When there wasn't enough pepper, its price would go up very quickly.

In 1580, Portugal joined with Spain under one ruler. Since the Dutch Republic was at war with Spain, Portugal's empire became a target for Dutch attacks. These events pushed Dutch merchants to start their own spice trade across the oceans. Explorers like Jan Huyghen van Linschoten and Cornelis de Houtman learned the secret Portuguese trade routes. This gave the Dutch a great chance to join the valuable spice business.

Soon, Dutch ships began sailing to the Indonesian islands. Early expeditions included those led by Cornelis de Houtman in 1595 and Jacob Van Neck in 1598. Houtman's first trip to Banten, a major pepper port, involved clashes with Portuguese and local Javanese people. His crew faced many dangers, losing half their members. Yet, they returned to the Netherlands in 1596 with enough spices to make a good profit.

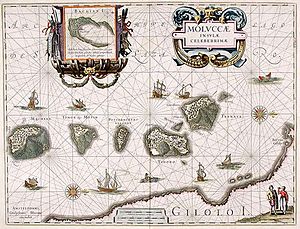

By 1598, many Dutch merchant groups were sending their own fleets to Asia. While some ships were lost, most trips were very successful and brought huge profits. That year, a fleet of eight ships led by Jacob van Neck reached the famous 'Spice Islands' (Maluku). They bypassed the usual Javanese traders. This expedition made an incredible 400 percent profit when the ships returned in 1599 and 1600.

In 1600, the Dutch teamed up with the Muslim Hituese people on Ambon Island against the Portuguese. In return, the Dutch gained the sole right to buy spices from Hitu. The Portuguese later gave up their fort in Ambon to this Dutch-Hituese alliance. The Dutch also took over a Portuguese fort on Solor island in 1613. However, the Portuguese briefly recaptured it before the Dutch took it back for good in 1636.

East of Solor, on the island of Timor, the Dutch faced strong resistance from a powerful group of Portuguese Eurasians called the Topasses. They controlled the valuable Sandalwood trade. Their fight against the Dutch lasted for many years, keeping Portuguese Timor under Portuguese control.

Building the Company's Power

In the early days, companies were often funded for just one trip and then closed. Investing in these trips was very risky due to pirates, diseases, and shipwrecks. Also, too many spices could make prices drop, ruining profits. To handle this, companies started working together. In 1600, the English formed their own monopoly, the English East India Company.

In 1602, the Dutch government created the VOC, giving it a monopoly over Asian trade. For a time, the VOC controlled the trade of nutmeg, mace, and cloves. They sold these spices in Europe and the Mughal Empire for 14 to 17 times what they paid in Indonesia.

While the Dutch made huge profits, the local economies in the Spice Islands suffered. The VOC, as the only buyer, forced down the prices paid to local farmers. The new company started with 6.4 million guilders. Its charter allowed it to build forts, keep armies, and make treaties with Asian rulers. The company was set up to last for 21 years, with financial reports every decade.

In February 1603, the VOC captured the Santa Catarina, a large Portuguese merchant ship, near the Malay Peninsula. Later that year, Dutch and English forces captured another Portuguese ship near Macau. The money from selling the goods on these two ships was worth more than half of the VOC's starting capital.

In 1603, the first permanent Dutch trading post in Indonesia was set up in Banten, West Java. Another was established in Jayakarta in 1611. To better manage its business in Asia, the VOC created the position of governor-general in 1610. A "Council of the Indies" was also formed to advise and oversee the governor-general. The governor-general became the main leader of the VOC's operations in Asia, though the "Heeren XVII" (Lords Seventeen) in the Dutch Republic still had overall control.

The VOC's first headquarters were in Ambon (1610–1619), but it wasn't ideal. It was in the spice-producing area but far from other Asian trade routes. So, the company looked for a location further west. The Strait of Malacca was important but dangerous due to Portuguese control. The first Dutch settlement in Banten was also challenging, with a powerful local ruler and competition from Chinese and English traders.

In 1604, a second English East India Company voyage reached the islands of Ternate, Tidore, Ambon, and Banda. In Banda, they faced strong opposition from the VOC, leading to competition for spices. From 1611 to 1617, the English set up trading posts in various parts of Indonesia, threatening the Dutch goal of a spice monopoly.

In 1620, agreements in Europe led to a period of cooperation between Dutch and English spice traders. This ended with the terrible Amboyna massacre, where ten Englishmen were executed for plotting against the Dutch. This caused anger in Europe, but the English mostly left Indonesia, focusing on other parts of Asia.

Expanding Trade and Influence

In 1619, Jan Pieterszoon Coen became the governor-general of the VOC. He believed the VOC could become a major political and economic power in Asia. On May 30, 1619, Coen, with 19 ships, attacked Jayakarta. He drove out the local forces and built Batavia as the new VOC headquarters. In the 1620s, many people in the Banda Islands were killed or forced to leave their homes. This was done to replace them with Dutch plantations for growing nutmeg. Coen wanted many Dutch colonists to move to the East Indies, but few were willing to go.

Coen had another successful idea. Europeans often had to pay for Asian goods with silver and gold, which were scarce in Europe. Coen realized the VOC could trade goods within Asia itself. The profits from this "intra-Asiatic trade" could then fund the spice trade with Europe. This meant less precious metal had to be sent from Europe. The VOC invested a lot of its profits into this system until 1630.

The VOC traded across Asia, especially benefiting from Bengal. Ships from the Netherlands brought supplies to VOC settlements. Silver and copper from Japan were used to trade with wealthy empires like Mughal India and Qing China. They bought silk, cotton, porcelain, and textiles. These items were then traded for spices in Asia or sent back to Europe. The VOC also brought European ideas and technology to Asia. They supported Christian missionaries and traded modern technology with China and Japan.

On Dejima, an artificial island near Nagasaki, the VOC had a peaceful trading post. For over 200 years, this was the only place where Europeans could trade with Japan. When the VOC tried to force Ming dynasty China to trade using military power, the Chinese defeated them in a war over the Penghu islands (1623–1624). This forced the VOC to leave Penghu for Taiwan. The Chinese defeated the VOC again in 1633.

The Vietnamese Nguyen lords defeated the VOC in a battle in 1643, blowing up a Dutch ship. The Cambodians also defeated the VOC in a war on the Mekong River from 1643 to 1644.

In 1640, the VOC took the port of Galle in Ceylon from the Portuguese, breaking their control over the cinnamon trade. In 1658, Gerard Pietersz Hulft captured Colombo with help from King Rajasinghe II of Kandy. By 1659, the Portuguese were driven from the coastal areas, giving the VOC a monopoly on cinnamon. To prevent the Portuguese or English from retaking Sri Lanka, the VOC conquered the entire Malabar Coast from the Portuguese, almost completely removing them from western India.

In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck set up a resupply station at the Cape of Storms (now Cape Town, South Africa). This was for company ships traveling to and from East Asia. The cape was later renamed Cape of Good Hope. Other ships could use the station but were charged high fees. This post eventually grew into a full colony, the Cape Colony, as more Dutch and other Europeans settled there.

Throughout the 1600s, VOC trading posts were also established in Persia, Bengal, Malacca, Siam, and Formosa (now Taiwan). They also had posts on the Malabar and Coromandel coasts in India. Direct trade with mainland China began in 1729 with a factory in Canton. In 1661, Ming general Koxinga led a fleet to defeat the Dutch. After Koxinga's forces defeated Dutch reinforcements in 1662, the Dutch commander surrendered Taiwan.

In 1663, the VOC signed the "Painan Treaty" with local lords in the Painan area. These lords were rebelling against the Aceh Sultanate. The treaty allowed the VOC to build a trading post and eventually control the trade there, especially the gold trade.

By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company ever seen. It had over 150 merchant ships, 40 warships, 50,000 employees, and a private army of 10,000 soldiers. It paid a huge 40% profit on the original investments. Many VOC employees married local people, leading to a mixed population.

Changing Times and New Challenges

Around 1670, the VOC's trade growth slowed down. First, the very profitable trade with Japan began to decline. The loss of the Formosa outpost to Koxinga in 1662 and unrest in China ended the silk trade after 1666. Although the VOC found new silk sources, Japan also limited the export of silver and gold. This made trade with Japan less favorable for the VOC by 1685.

More importantly, the Third Anglo-Dutch War temporarily stopped VOC trade with Europe. This caused pepper prices to rise sharply, encouraging the English East India Company (EIC) to enter the market aggressively after 1672. The VOC usually kept pepper prices low to discourage competitors. A fierce price war with the EIC followed, as the English flooded the market with new supplies. The VOC, with its greater financial resources, eventually outlasted the EIC. By 1683, the EIC was almost bankrupt.

However, other companies like the French and Danish East India Companies also started to challenge the Dutch. The VOC closed the busy pepper market of Bantam in 1684 through a treaty. On the Coromandel Coast, it moved its main base to Nagapattinam to secure a pepper monopoly against the French and Danes. But the importance of these traditional spices in Asian-European trade was quickly decreasing. The military costs to maintain these monopolies were no longer worth the profits.

This lesson was slow to be learned. At first, the VOC tried to strengthen its military position on the Malabar Coast. They hoped to reduce English influence and save money on garrisons. In 1710, the local ruler of Calicut was forced to sign a treaty to trade only with the VOC. This seemed to help for a short time. However, in 1715, with English encouragement, the ruler broke the treaty. Even after a Dutch army put down a rebellion, the ruler continued trading with the English and French. By 1721, the VOC decided it was no longer worth trying to control the Malabar pepper trade. They reduced their military presence and effectively gave the area to English influence.

In the 1741 Battle of Colachel, warriors from Travancore under Raja Marthanda Varma defeated the Dutch. The Dutch commander, Captain Eustachius De Lannoy, was captured. Marthanda Varma spared his life on the condition that he joined his army and trained his soldiers. This defeat showed that an organized Asian power could overcome European military technology. It marked the decline of Dutch power in India.

The VOC's strategy of focusing on low-volume, high-profit spice trade was failing. The company had to (reluctantly) follow its European rivals and diversify into other Asian goods. These included tea, coffee, cotton, textiles, and sugar. These items had lower profit margins, so the VOC needed to sell much larger quantities to make the same amount of money. This shift in trade began in the early 1680s.

Two main reasons caused this change. First, European tastes changed dramatically around 1700, with a new demand for Asian textiles, coffee, and tea. Second, there was a new era of easily available money at low interest rates. This allowed the company to easily fund its expansion into these new areas of trade. Between the 1680s and 1720s, the VOC greatly expanded its fleet and acquired much precious metal to buy Asian goods for Europe. This effectively doubled the company's size.

The amount of goods brought back by ships increased by 125% during this time. However, the money the company made from selling these goods in Europe only rose by 78%. This showed a basic change: the VOC was now in new markets with more competition and lower profit margins. The company's managers found this hard to understand at the time. The directors, who were mostly politicians, had also lost touch with merchant circles.

Low profit margins alone don't explain the drop in income. Many of the VOC's costs, like military expenses and fleet maintenance, were fixed. Profits could have been maintained if the increased trade volume led to greater efficiency. However, even with larger ships, worker productivity didn't rise enough. Overall, the company's costs grew with trade volume, leading to lower profits on invested capital. This period of expansion was one of "profitless growth."

For example, the average annual profit in the VOC's "Golden Age" (1630–1670) was 2.1 million guilders. About half was paid as dividends, and the rest was reinvested. In the "Expansion Age" (1680–1730), the average annual profit was 2.0 million guilders. But three-quarters was paid as dividends, and only one-quarter reinvested. Profits dropped from 18% of total revenues to 10%. The return on invested capital fell from 6% to 3.4%.

Despite these issues, investors still saw the VOC as a good investment. The share price stayed around 400 from the mid-1680s and reached a high of about 642 in the 1720s. VOC shares offered a return of 3.5%, only slightly less than Dutch government bonds.

Why the VOC Declined and Ended

After 1730, the VOC's fortunes began to worsen. Five main reasons contributed to its decline between 1730 and 1780:

- Trade within Asia slowly decreased. This was due to political and economic changes in Asia that the VOC couldn't control. The company was gradually pushed out of Persia, Suratte, the Malabar Coast, and Bengal. Its operations became limited to the areas it physically controlled, from Ceylon through Indonesia. This meant less trade and lower profits.

- The company's organization in Asia, centered in Batavia, became inefficient. Everything had to be shipped to this central point first. This was a big problem for the tea trade, where competitors shipped directly from China to Europe.

- Corruption among VOC employees was a major issue. While other East India Companies also faced this, it seemed worse for the VOC. Salaries were low, and private trading by employees was officially forbidden but happened a lot. This hurt the company's performance. By the 1790s, people joked that VOC stood for "perished under corruption."

- High rates of illness and death among its employees weakened the company. Many workers died, and survivors were often too sick to work effectively.

- The VOC's dividend policy also caused problems. The company paid out more in profits to shareholders than it earned in Europe for most decades between 1690 and 1760. While they initially invested money in Asia, after 1730, profits dropped, but directors barely lowered dividends. This meant the company had to use its capital in Asia and Europe to pay shareholders. They had to borrow money to stay afloat.

Despite these problems, the VOC was still a huge operation in 1780. Its assets in the Netherlands (ships, goods) were worth 28 million guilders. Its assets in Asia (trading funds, goods en route) were 46 million guilders. The company's total value, after debts, was 62 million guilders. So, its situation wasn't hopeless if reforms had been made. However, in 1780, the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War broke out. British attacks cut the VOC's fleet in half and severely weakened its position in Asia. The war caused damages of up to 43 million guilders. Loans to keep the company running wiped out its remaining value.

From 1720 onwards, the market for sugar from Indonesia declined. This was because cheap sugar from Brazil created more competition. European markets became flooded. Many Chinese sugar traders went bankrupt, leading to widespread unemployment and gangs of jobless workers. The Dutch government in Batavia didn't handle these problems well. In 1740, rumors of deporting these gangs led to riots. The Dutch military searched Chinese homes for weapons. When a house accidentally burned down, soldiers and poor citizens began attacking and harming the Chinese community. This massacre of the Chinese was so serious that the VOC board launched its first official investigation into the Dutch East Indies government.

After the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War ended in 1783, the VOC's financial problems grew much worse. After failed attempts to reorganize, the VOC's directors were dismissed in 1796. A new committee took over the company's management. The start of the French Revolutionary Wars sealed the VOC's fate. The fall of the Dutch Republic and its replacement by the Batavian Republic in 1795 meant the Dutch and British were now at war. British attacks on VOC ships and settlements led to more losses. Although the VOC's charter was renewed several times, it was allowed to expire on December 31, 1799, and the company became part of the government.

How the VOC Was Organized

The VOC mainly operated in what is now Indonesia, but it also had important operations elsewhere. It hired people from many different places and backgrounds for the same jobs. Although it was a Dutch company, its employees came from the Netherlands, Germany, and other countries. The VOC also hired many local Asian workers. So, its offices in Asia had both European and Asian employees. Asian workers could be sailors, soldiers, writers, carpenters, smiths, or simple laborers. At its peak, the VOC had 25,000 employees in Asia and 11,000 traveling by sea. Most shareholders were Dutch, but about a quarter of the first investors were from what is now Belgium and Luxembourg, and some were German.

The VOC had two types of shareholders: participanten, who were like regular investors, and 76 bewindhebbers (later 60), who were the managing directors. This was common for Dutch joint-stock companies. The new thing about the VOC was that both types of shareholders had "limited liability." This meant they were only responsible for the money they invested, not more. Also, the company's capital was "permanent." Investors who wanted to sell their shares could only do so by selling them to others on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. A book from 1688, Confusion of confusions, by Joseph de la Vega, described how this stock exchange worked.

The VOC had six main offices, called Chambers (Kamers), in port cities: Amsterdam, Delft, Rotterdam, Enkhuizen, Middelburg, and Hoorn. Representatives from these chambers met as the Heeren XVII (the Lords Seventeen). They were chosen from the bewindhebber shareholders.

Of the Heeren XVII, eight delegates were from the Amsterdam Chamber, four from Zeeland, and one from each of the smaller Chambers. The seventeenth seat rotated. This meant Amsterdam had the most power. The Zeelanders were worried about this arrangement, and their fears were true, as Amsterdam often made the final decisions.

The six chambers raised the starting money for the Dutch East India Company:

| Chamber | Capital (Guilders) |

|---|---|

| Amsterdam | 3,679,915 |

| Middelburg | 1,300,405 |

| Enkhuizen | 540,000 |

| Delft | 469,400 |

| Hoorn | 266,868 |

| Rotterdam | 173,000 |

| Total: | 6,424,588 |

Raising money in Rotterdam was a bit harder, with many investors coming from Dordrecht. Although Enkhuizen didn't raise as much capital as Amsterdam or Middelburg-Zeeland, it had the largest number of individual investors. The minimum investment was 3,000 guilders, making it possible for many merchants to buy shares.

Many immigrants played an important role among the early VOC shareholders. Among the first 1,143 investors, 39 were German and 301 were from the Southern Netherlands (modern Belgium and Luxembourg). Isaac le Maire was the largest investor, with ƒ85,000. The Heeren XVII met alternately in Amsterdam and Middelburg-Zeeland. They set the VOC's general rules and divided tasks among the Chambers. The Chambers handled all the work, built ships and warehouses, and traded goods. The Heeren XVII gave ship captains detailed instructions on routes, winds, currents, and landmarks. The VOC also created its own maps.

During the Dutch–Portuguese War, the company set up its headquarters in Batavia, Java (now Jakarta, Indonesia). Other trading outposts were also established in the East Indies, such as on the Maluku Islands. This included the Banda Islands, where the VOC used force to maintain a monopoly over nutmeg and mace. To keep this monopoly, they used harsh methods, including violence against the local population. VOC representatives sometimes burned spice trees to force local people to grow other crops, artificially reducing the supply of spices like nutmeg and cloves.

Early Investor Voices and Company Rules

Dutch businessmen in the 1600s, especially VOC investors, were perhaps the first to seriously think about how companies should be run. Isaac Le Maire, known as the first recorded "short seller," was also a big VOC shareholder. In 1609, he complained about the VOC's management. On January 24, 1609, Le Maire filed a petition against the VOC. This was the first recorded example of a shareholder speaking up. In this first corporate governance dispute, Le Maire claimed the VOC's directors (the Heeren XVII) wanted to "keep another's money for longer or use it in ways other than the latter wishes." He asked for the VOC to be closed, as was standard business practice. Le Maire, who was once the largest shareholder and a director, had tried to make profits for himself through his own expeditions. Since his large shares didn't give him more voting power, other directors removed him in 1605 for misusing company funds. He was forced to agree not to compete with the VOC. Still owning shares, Le Maire wrote what is considered the "first recorded expression of shareholder advocacy" in 1609.

In 1622, the first recorded "shareholder revolt" happened among VOC investors. They complained that the company's account books were unclear, saying they had been "smeared with bacon" so that they might be "eaten by dogs." The investors demanded a proper financial audit. This 1622 campaign by VOC shareholders showed the beginning of "corporate social responsibility." Shareholders protested by handing out flyers and complaining about management enriching themselves and keeping secrets.

Key Trading Posts and Settlements

The company's main headquarters were in Amsterdam. Other offices were in the Dutch cities of Delft, Enkhuizen, Hoorn, Middelburg, and Rotterdam. In Africa, the VOC had trading posts and settlements in Dutch Mauritius (1638-1658 and 1664–1710) and the Dutch Cape Colony (1652–1806). The company's South Asian and Indonesian posts included Batavia, Dutch East Indies, Dutch Coromandel (1806–1825), Dutch Suratte (1616-1825), Dutch Bengal (1827–1825), Dutch Ceylon (1640–1796), and Dutch Malabar (1661–1795).

The Japanese post was in Hirado, Nagasaki (1609–1641), then moved to Dejima (1641–1853). In Taiwan, the company had bases in Anping (Fort Zeelandia), Tainan (Fort Provincia), Wang-an, Penghu on the Pescadores Islands (Fort Vlissingen; 1620–1624), Keelung (Fort Noord-Holland and Fort Victoria), and Tamsui (Fort Antonio).

In Malaysia, the company was based in Dutch Malacca (1641-1795 and 1818–1825). In Thailand, the company was based in Ayutthaya (1608–1767). In Vietnam, the company had bases in Hanoi/Tonkin (1636–1699) and in Hội An (1636–1741).

The "VOC Mentality" Debate

(...) I don't understand why you're all being so negative and unpleasant. Let's just be happy with each other. Let's just say "the Netherlands can do it" again: that VOC mentality. Look across our borders. Dynamism! Don't you think?

The VOC's history, especially its darker aspects, has always been a topic of discussion. In 2006, the former Dutch Prime Minister Jan Pieter Balkenende used the term "VOC mentality" (VOC-mentaliteit) to describe the pioneering spirit and business drive of the Dutch during their Golden Age.

For Balkenende, the VOC represented Dutch business skill, entrepreneurship, adventurous spirit, and determination. However, this sparked a lot of criticism. Many felt that such a positive view of the Dutch Golden Age ignored the historical connections to colonialism, exploitation, and violence. Balkenende later clarified that he "had not intended to refer to that at all." Despite the criticism, the "VOC-mentality" has been seen as a key part of how Dutch cultural policy views the Golden Age for many years.

Preserving the VOC's History

The VOC's operations created not only warehouses full of spices, coffee, tea, textiles, porcelain, and silk, but also many documents. Information about political, economic, cultural, religious, and social conditions across a huge area was shared between VOC settlements, the main administrative center in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta), and the directors (the Heeren XVII/Gentlemen Seventeen) in the Dutch Republic. Twenty-five million pages of VOC records still exist today. They are kept in Jakarta; Colombo, Sri Lanka; Chennai, India; Cape Town, South Africa; and The Hague, the Netherlands. In 2003, UNESCO added this collection of records to its Memory of the World international register, recognizing their global importance.

See also

- East India Company (disambiguation)

- Muscovy Company

- Levant Company

- British East India Company

- Danish East India Company

- Dutch West India Company

- Portuguese East India Company

- Compagnie des Indes

- Danish West India Company

- Hudson's Bay Company

- Mississippi Company

- South Sea Company

- Ostend Company

- Swedish East India Company

- Emden Company

- Austrian East India Company

- Swedish West India Company

- Russian-American Company

- 10649 VOC, a minor planet, the asteroid VOC (Dutch: Vereeniging van de Oostindische Compagnie, lit. 'East India Company'), the 10649th asteroid registered, a main-belt asteroid

See also

In Spanish: Compañía Neerlandesa de las Indias Orientales para niños

In Spanish: Compañía Neerlandesa de las Indias Orientales para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |