History of New Zealand facts for kids

The history of New Zealand (Aotearoa) began between 1320 and 1350 CE. This is when the first people, Polynesians, discovered and settled the islands. They developed a unique Māori culture. Unlike other Pacific cultures, Māori society was built around family connections and a strong bond with the land. It also adapted to New Zealand's cooler climate, which was different from the warm, tropical islands they came from.

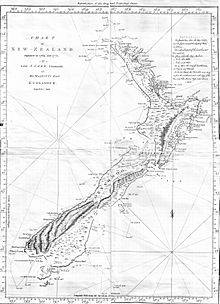

The first European explorer known to visit New Zealand was Dutch sailor Abel Tasman. He arrived on December 13, 1642. In 1643, he mapped the west coast of the North Island but didn't land. British explorer James Cook reached New Zealand in October 1769. He was the first European to sail all the way around and map New Zealand. From the late 1700s, more explorers, sailors, missionaries, traders, and adventurers visited the country.

In 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. This agreement was between representatives of the United Kingdom and various Māori chiefs. It brought New Zealand into the British Empire and aimed to give Māori the same rights as British citizens. However, disagreements over how the Treaty was translated and the desire of settlers to buy Māori land led to the New Zealand Wars starting in 1843. Many British settlers arrived throughout the rest of the 1800s and early 1900s. European diseases, the New Zealand Wars, and new European laws and economy meant that much of New Zealand's land moved from Māori to Pākehā (European) ownership. This made many Māori poor.

New Zealand gained responsible government in the 1850s, meaning local leaders could make decisions. From the 1890s, the New Zealand Parliament introduced new laws. These included giving women the right to vote and creating old age pensions. New Zealand became a self-governing Dominion within the British Empire in 1907. It remained a strong supporter of the empire, and over 100,000 New Zealanders fought in World War I. After the war, New Zealand signed the Treaty of Versailles (1919) and joined the League of Nations. It started to make its own foreign policy decisions, but Britain still controlled its defense. When World War II began in 1939, New Zealand helped defend Britain and fought in the Pacific War. About 120,000 troops from New Zealand took part.

From the 1930s, the government controlled the economy more, and a large welfare system was created. From the 1950s, Māori started moving to cities in large numbers. This led to a Māori renaissance, a time of renewed interest and pride in Māori culture. A Māori protest movement also grew, which led to the Treaty of Waitangi being recognized more in the late 1900s.

The country's economy struggled after the 1973 global energy crisis. Britain also joined the European Economic Community, meaning New Zealand lost its biggest export market. There was also a lot of inflation. In 1984, the Fourth Labour Government was elected during a time of economic trouble. The government changed the economy to a more "free market" system. After 1984, New Zealand's foreign policy became more independent, especially in pushing for a nuclear-free zone. Later governments generally kept these policies, though they made the free market ideas a bit softer.

Contents

Māori Arrival and Early Life

New Zealand was first settled by Polynesians from the eastern Pacific. Scientists believe that people traveled from Taiwan through Southeast Asia to Melanesia. From there, they spread eastward into the Pacific, discovering and settling islands like Samoa, Tonga, Hawaii, Easter Island, and finally, New Zealand.

There are no human items or remains in New Zealand that are older than the Kaharoa Tephra. This is a layer of volcanic ash from the Mount Tarawera eruption around 1314 CE. Some scientists thought that widespread forest fires before the eruption might mean humans were there earlier. However, the most recent studies suggest that the main settlement happened after the eruption, between 1320 and 1350 CE. This might have been a large, planned migration. Old Māori family histories also suggest 1350 AD as a likely arrival date for the main canoes.

The descendants of these settlers became known as the Māori. They developed their own unique culture. Later, around 1500 CE, some Māori settled the tiny Chatham Islands to the east of New Zealand. These people became the Moriori. There is no evidence that any other group lived in mainland New Zealand before the Māori.

The first settlers quickly hunted the large animals in New Zealand, like the moa. Moa were huge flightless birds that became extinct by about 1500. As moa and other large game became harder to find, Māori culture changed a lot. In areas where taro and kūmara (sweet potato) could grow, gardening became very important. This wasn't possible in the south of the South Island. Instead, people gathered wild plants like fernroot and harvested cabbage trees for food.

Warfare also became more common as groups competed for land and resources. During this time, fortified villages called pā became more widespread.

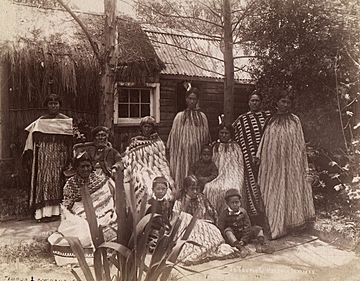

Leadership was based on a system of chieftainship. Chiefs, both male and female, often inherited their roles. However, they also needed to show strong leadership skills. The most important groups in Māori society before Europeans arrived were the whānau (extended family) and the hapū (a group of whānau). Above these was the iwi (tribe), made up of several hapū. Related hapū often traded goods and worked together on big projects. But conflicts between hapū were also common.

Traditional Māori society passed down history through stories, songs, and chants. Skilled experts could recite tribal family trees (whakapapa) going back hundreds of years. Māori arts included oratory (public speaking), composing songs, and dance forms like haka. They also excelled at weaving, detailed wood carving, and tā moko (tattooing).

New Zealand has no native land mammals except for some rare bats. So, birds, fish, and sea mammals were important sources of food. Māori grew food plants they brought from Polynesia. These included sweet potatoes (kūmara), taro, gourds, and yams. They also grew the cabbage tree, a plant found only in New Zealand. They also used wild foods like fern root, which provided a starchy paste.

Early European Contact

First Explorers

The first Europeans known to reach New Zealand were the crew of Dutch explorer Abel Tasman. He arrived in his ships Heemskerck and Zeehaen. Tasman anchored in Golden Bay (which he called Murderers' Bay) in December 1642. After an attack by local Māori, Ngāti Tūmatakōkiri, he sailed north to Tonga. Tasman drew maps of parts of the two main islands' west coasts. He named them Staten Landt. In 1645, Dutch mapmakers changed the name to Nova Zeelandia in Latin, from Nieuw Zeeland, after the Dutch province of Zeeland.

Over 100 years passed before Europeans returned. In 1769, British naval captain James Cook on HM Bark Endeavour visited New Zealand. By chance, just two months later, Frenchman Jean-François de Surville also reached the country. Cook returned to New Zealand on his next two voyages as well.

From the 1790s, British, French, and American whaling, sealing, and trading ships visited New Zealand's waters. Their crews traded European goods, like guns and metal tools, for Māori food, water, and wood. Māori were known as keen and clever traders. Even though there were some conflicts, most contact between Māori and Europeans was peaceful.

Early European Settlers

More European (Pākehā) settlers arrived in the early 1800s. Many trading posts were set up, especially in the North Island. Christianity was brought to New Zealand in 1814 by Samuel Marsden. He started a mission station in the Bay of Islands. By 1840, over 20 mission stations had been created. From missionaries, Māori learned about Christianity, European farming, and how to read and write. In 1820, linguist Samuel Lee worked with Māori chief Hongi Hika to write down the Māori language. In 1835, the first successful printing in the country was two books from the Bible, translated into Māori.

The first European settlement was at Rangihoua Bay. Land was bought there on February 24, 1815. Kerikeri, founded in 1822, and Bluff, founded in 1823, both claim to be the oldest European settlements in New Zealand. Many European settlers bought land from Māori. However, different ideas about land ownership often led to arguments and bad feelings.

Colonial Period

New Zealand was first managed from Australia as part of the Colony of New South Wales. But these rules didn't have much real effect. In 1832, the British Government appointed James Busby as British Resident in New Zealand. This was because missionaries complained about lawless sailors and adventurers. In 1834, Busby encouraged Māori chiefs to declare their independence by signing the Declaration of Independence in 1835. Britain recognized this declaration. However, Busby had no real power or military support, so he couldn't control the European population.

Treaty of Waitangi

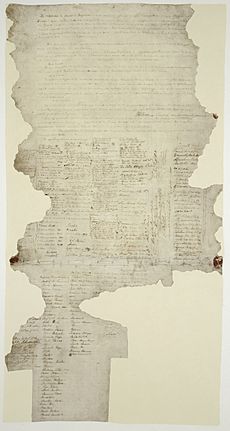

In 1839, the New Zealand Company announced plans to buy large areas of land and set up colonies in New Zealand. This, along with growing business interests, pushed the British Government to act. Captain William Hobson was sent to New Zealand. His job was to convince Māori to give their sovereignty (power to rule) to the British Crown.

On February 6, 1840, Hobson and about forty Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi at Waitangi. The British then took copies of the Treaty around New Zealand for other chiefs to sign. Many chiefs refused to sign, or were not asked. But in total, over five hundred Māori eventually signed.

The Treaty gave Māori power over their lands and belongings, and all the rights of British citizens. What it gave the British depends on which language version of the Treaty you read. The English version seems to give the British Crown sovereignty over New Zealand. But in the Māori version, the Crown receives kāwanatanga, which means a lesser power, like governorship. The debate over the "true" meaning of the Treaty is still an issue today.

Britain wanted to stop the New Zealand Company and other European countries (like France) from taking over. They also wanted to make it easier for British people to settle and to stop the lawlessness of European whalers and traders. Māori chiefs wanted protection from foreign powers. They also wanted the British to govern European settlers and traders, and to allow more European settlement for trade and prosperity.

Establishing the Colony

At first, New Zealand was managed from Australia. But in May 1841, New Zealand became its own colony. Settlement continued under British plans. In 1846, the British Parliament passed a law for self-government for the 13,000 settlers in New Zealand. However, the new Governor, George Grey, stopped these plans. He argued that the Pākehā could not be trusted to protect Māori interests, as there had already been Treaty violations.

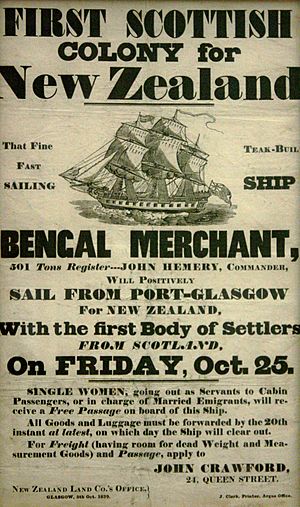

The Church of England helped set up the Canterbury Association colony in the early 1850s, offering assisted travel from Britain. Because of many new settlers, the Pākehā population grew very quickly. It went from fewer than 1,000 in 1831 to 500,000 by 1881. About 400,000 settlers came from Britain, and 300,000 stayed permanently. Most were young people, and 250,000 babies were born.

New Zealand Wars

Māori had welcomed Pākehā for the trading chances and guns they brought. But soon it became clear that they had underestimated how many settlers would arrive. Iwi (tribes) whose land was near the main settlements quickly lost much of their land and control. Others did well. Until about 1860, the city of Auckland bought most of its food from Māori who grew and sold it. Many iwi owned flour mills, ships, and other European technology. Some even exported food to Australia during the 1850s gold rush. Although relations were generally peaceful, there were arguments over who had the most power in certain areas. One such conflict was the Northern or Flagstaff War of the 1840s.

As the Pākehā population grew, there was more pressure on Māori to sell land. Land was used by the whole community under the authority of chiefs. In Māori culture, the idea of "selling" land didn't exist until Europeans arrived. Land was usually gained by defeating another hapu or iwi in battle. Land was not usually given up without discussion. When an iwi was divided over selling land, it could lead to big problems.

Pākehā didn't fully understand Māori views on land. They accused Māori of holding onto land they didn't use "efficiently." Competition for land was a major cause of the New Zealand Wars in the 1860s and 1870s. During these wars, the Taranaki and Waikato regions were invaded by colonial troops. Māori in these regions had some of their land taken from them. The wars and land confiscations left bad feelings that still exist today.

Some iwi sided with the government and fought alongside them. They hoped an alliance with the government would benefit them. They also had old rivalries with the iwi they fought against. One result of their cooperation was the creation of four Māori electorates in Parliament in 1867.

After the wars, some Māori began to resist peacefully. The most famous example was the ploughing campaigns at Parihaka in Taranaki in 1879. Most iwi, like NgaPuhi and Arawa, continued to work with Pākehā. For example, Te Arawa started tourism businesses around Rotorua. Both resisting and cooperating iwi found that Pākehā still wanted their land. In the late 1800s, most iwi lost a lot of land through the actions of the Native Land Court. This court's rules, high fees, and unfair practices by some Pākehā land agents often made it easier for Māori to sell their land without tribal agreement.

Diseases, war, land confiscations, and other factors caused the Māori population to fall. It went from around 86,000 in 1769 to about 70,000 in 1840, and then to a low of 42,000 in 1896. After that, their numbers began to grow again.

Self-Government, 1850s

As more British settlers arrived, they asked for self-governance. In response, the British Parliament passed the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. This set up a central government with an elected General Assembly and six provincial governments. The settlers soon gained the right to responsible government. This meant that the executive government was supported by the elected assembly. However, the governor and London still controlled policies related to Māori until the mid-1860s.

Farming and Mining

At first, Māori tribes sold land to settlers. But the government made these sales invalid in 1840. After that, only the government could buy land from Māori, who received cash. The government bought almost all the useful land. Then, it resold it to the New Zealand Company, which encouraged immigration, or leased it for sheep farms.

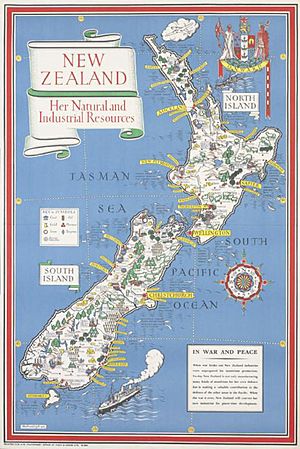

Because of the huge distances, the first settlers were self-sufficient farmers. But by the 1840s, large sheep farms were sending huge amounts of wool to England. Most early settlers came through a program run by the New Zealand Company. They settled in the central region, including Wellington, Wanganui, New Plymouth, and Nelson. These settlements had access to some of the richest plains. After refrigerated ships appeared in 1882, these areas became closely settled regions with small farms.

Gold discoveries in Otago (1861) and Westland (1865) caused a worldwide gold rush. This more than doubled the population quickly, from 71,000 in 1859 to 164,000 in 1863. The value of trade increased five times. As the gold boom ended, Colonial Treasurer Julius Vogel borrowed money from British investors. In 1870, he started a big program of public works and infrastructure, like railways and roads. He also encouraged assisted immigration.

From about 1865, the economy went into a long downturn. This was due to British troops leaving, gold production peaking, and Vogel's borrowing creating debt. Prices for farm products fell. Hard times led to unemployment in cities. Many people left New Zealand, mostly for Australia.

Vogel Era Developments

In 1870, Julius Vogel started his "grand go-ahead policy." He aimed to end the economic slump by increasing immigration and borrowing money from overseas. This money funded new railways, roads, and telegraph lines. The public debt grew from £7.8 million in 1870 to £18.6 million in 1876. But 718 miles (1,155 km) of railway were built, and 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of road were opened. Electric telegraph lines also greatly increased. A record number of immigrants arrived in 1874 (32,000 of 44,000 were government-assisted). The population rose from 248,000 in 1870 to 399,000 in 1876.

Women's Rights

Even though men's roles were dominant, strong women started a feminist movement in the 1860s. This was well before women gained the right to vote in 1893. Middle-class women used newspapers to share ideas and decide their goals. Important feminist writers included Mary Taylor and Mary Ann Colclough.

Māori women developed their own type of feminism, which came from Māori nationalism rather than European ideas.

In 1893, Elizabeth Yates was elected mayor of Onehunga. This made her the first woman in the British Empire to hold such an office. She was a good leader: she cut debt, reorganized the fire brigade, and improved roads and sanitation. However, many men were against her, and she lost re-election. After 1890, women became very organized through groups like the National Council of Women of New Zealand. By 1910, they were campaigning for peace and against forced military training. They argued that women, because of motherhood, had better moral values and knew best how to solve conflicts.

Education

Before 1877, schools were run by local governments, churches, or private groups. Education was not required, and many children, especially farm children, did not attend school. The quality of education varied a lot. The Education Act of 1877 created New Zealand's first free national system of primary education. It set standards for teachers and made education compulsory for children aged 5 to 15.

Immigration and South Island Growth

From 1840, many Europeans settled in New Zealand. Most came from England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Some also came from the United States, India, China, and parts of Europe like Croatia and the Czech Republic. By 1859, Europeans were already the majority. Their numbers quickly grew to over one million by 1916.

In the 1870s and 1880s, thousands of Chinese men, mostly from Guangdong, came to New Zealand to work in the South Island goldfields. Although the first Chinese migrants were invited, they soon faced hostility from white settlers. Laws were made specifically to discourage them from coming to New Zealand.

In 1861, gold was found at Gabriel's Gully in Central Otago, starting a gold rush. Dunedin became the richest city in the country. Many people in the South Island didn't like paying for the North Island's wars. In 1865, Parliament voted against a proposal to make the South Island independent.

The South Island had most of the Pākehā population until around 1911. Then, the North Island took the lead again. The North Island has continued to have a larger majority of the country's total population throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Scottish immigrants were very common in the South Island. They formed many local Caledonian societies. These groups organized sports for young people and kept alive an idealized Scottish national story. This helped Scots fit into New Zealand society as Scottish New Zealanders. The large number of Scots in the South Island is why Presbyterianism is still very common there.

Early 1900s: Politics and Economy

Politics and Reforms

Before World War I, party politics began with the Liberal Government. Before 1891, wealthy landowners largely controlled New Zealand politics. The Liberal Party aimed to change this with a policy called "populism." Their goal was to create a large group of small land-owning farmers who would support Liberal ideas.

To get land for farmers, the Liberal government (1891-1911) bought 3.1 million acres of Māori land. The government also bought 1.3 million acres from large landowners to divide into smaller farms for more settlers. The Advances to Settlers Act of 1894 provided low-interest loans for mortgages. The Agriculture Department shared information on the best farming methods.

The 1909 Native Land Act allowed Māori to sell land to private buyers. By 1920, Māori still owned five million acres. They leased three million acres and used one million acres for themselves. The Liberals claimed success in creating a fair land policy that was against monopolies. This policy gained support for the Liberal party in rural North Island areas. By 1903, the Liberals were so strong that there was no organized opposition in Parliament.

The Liberal government set up the basis for the later welfare state. They introduced old age pensions, rules for maximum working hours, and early minimum wage laws. They also developed a system for settling industrial disputes, which was accepted by both employers and trade unions at first. In 1893, New Zealand gave women the right to vote, making it the first country in the world to allow all women to vote.

New Zealand gained international attention for its reforms, especially how the government managed worker relations. These changes had a strong impact on the reform movement in the United States.

Economic Growth

In the 1870s, Julius Vogel's policy of borrowing money from overseas had increased public debt. But it also built many miles of railways, roads, and telegraph lines, and attracted many new immigrants.

In the 1880s, New Zealand's economy changed. It went from being based on wool and local trade to exporting wool, cheese, butter, and frozen meat to Britain. This change was possible because refrigerated steamships were invented in 1882. New Zealand's very productive agriculture gave it probably the world's highest standard of living. There were fewer very rich or very poor people.

During this time (around 1880-1914), the banking system was weak, and there was little foreign investment. So, business people had to build their own capital. New Zealanders found ways to succeed despite difficult conditions. Successful businesses used methods that saved capital and reinvested profits instead of borrowing. This led to slow but steady growth and long-lasting family-owned companies.

Dominion and World Wars

New Zealand was at first interested in joining the proposed Federation of the Australian colonies. But interest faded, and New Zealand decided not to join the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901. Instead, New Zealand changed from being a colony to a separate "Dominion" in 1907. This meant it had equal status to Australia and Canada. Dominion status showed that New Zealand had been governing itself for over 50 years. Just under one million people lived in New Zealand in 1907, and cities like Auckland and Wellington were growing fast.

First World War

New Zealand remained a strong supporter of the British Empire. World War I began on August 4. During the war, over 120,000 New Zealanders joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Around 100,000 served overseas. 18,000 died, 499 were taken prisoner, and about 41,000 men were wounded. Conscription (forced military service) had been in place since 1909. The labor movement was against the war, saying that rich people were benefiting at the expense of workers. They formed the New Zealand Labour Party in 1916. Māori tribes that were close to the government sent their young men to volunteer. Unlike in Britain, relatively few women were involved. Women did serve as nurses; 640 joined the services, and 500 went overseas.

New Zealand forces captured Western Samoa from Germany early in the war. New Zealand then governed the country until Samoa became independent in 1962. However, Samoans strongly disliked this rule.

More than 2,700 New Zealand men died in the Gallipoli Campaign. The bravery of the soldiers in this failed campaign became a very important part of New Zealand's history. It is often seen as helping the nation gain a sense of its own identity.

Between the Wars

After the war, New Zealand signed the Treaty of Versailles (1919) and joined the League of Nations. It started to make its own foreign policy decisions, but Britain still controlled its defense. New Zealand relied on Britain's Royal Navy for its military safety in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Labour Party became a strong force in 1919 with a socialist platform. It won about 25% of the vote. However, many working-class people voted for conservative parties. So, the Labour Party changed its policies to appeal to middle-class voters. This led to a big increase in their support. From 1935, the First Labour Government showed some idealism in foreign policy. For example, they were against Germany and Japan's aggressive actions.

Great Depression

Like many other countries, New Zealand suffered during the Great Depression of the 1930s. This affected the country through its international trade. Farm exports dropped sharply, which then affected money supply, spending, and imports. The country was most affected around 1930–1932. For a short time, average farm incomes fell below zero, and the unemployment rate was very high.

There were no unemployment benefits like today. Unemployed people were given "relief work," much of which was not very useful. Women also increasingly registered as unemployed. Māori received government help through other ways, like land-development schemes organized by Sir Āpirana Ngata.

Building the Welfare State

Attempts by the previous government to deal with the depression by cutting spending and offering relief work were not effective or popular. In 1935, the First Labour Government was elected. By then, economic conditions had improved a bit. Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage said that "Social Justice must be the guiding principle."

The new government quickly made many important changes. These included reorganizing the social welfare system and creating the state housing scheme. Labour also gained Māori votes by working closely with the Rātana movement. Savage was greatly admired by working-class people. The new welfare state promised government support to individuals "from the cradle to the grave." This included free health care and education, and state help for the elderly, sick, and unemployed. The opposition criticized Labour's policies, saying they harmed free enterprise. The Reform Party and the United Party merged to become the National Party. They became Labour's main rival. However, the welfare state system was kept and expanded by later National and Labour governments until the 1980s.

Second World War

When war broke out in 1939, New Zealanders felt it was their duty to defend their place in the British Empire. New Zealand sent about 120,000 troops. They mostly fought in North Africa, Greece/Crete, and Italy. New Zealand relied on the Royal Navy and later the United States to protect it from Japanese forces. Japan had little interest in New Zealand. The 3rd New Zealand Division fought in the Solomons in 1943–44. But New Zealand didn't have enough people to keep two divisions, so it was disbanded. Its men returned to civilian life or reinforced the 2nd Division in Italy. The armed forces reached their highest number, 157,000, in September 1942. 135,000 served abroad, and 10,100 died.

New Zealand, with a population of 1.7 million (including 99,000 Māori), was highly organized for the war. The Labour party was in power and encouraged unions and the welfare state. Agriculture grew, sending record amounts of meat, butter, and wool to Britain. When American forces arrived, they were also fed.

The nation spent £574 million on the war. 43% came from taxes, 41% from loans, and 16% from American Lend Lease aid. It was a time of prosperity as national income soared. Rationing and price controls kept inflation low.

The war greatly increased the roles of women, especially married women, in the workforce. Most took traditional female jobs. Some replaced men, but these changes were temporary and reversed in 1945. After the war, women left traditional male jobs, and many stopped paid work to return home. There wasn't a huge change in gender roles, but the war sped up job trends that had started in the 1920s.

Post-War Era

Political Changes

Labour stayed in power after World War II. In 1945, Labour Prime Minister Peter Fraser played an important role in setting up the United Nations. New Zealand was a founding member. However, at home, Labour had lost its desire for big reforms from the 1930s. Its support dropped after the war. After Labour lost power in 1949, the conservative National Party began to govern for almost 30 years straight. This was only broken by short Labour governments from 1957 to 1960 and 1972 to 1975. National Prime Minister Sidney Holland called a quick election after the 1951 waterfront dispute. This event strengthened National's power and greatly weakened the union movement.

Cooperation with the United States led to the ANZUS Treaty between New Zealand, America, and Australia in 1951. New Zealand also participated in the Korean War.

The British Connection and Changes

New Zealand culture in the 1950s was very British and traditional. New immigrants, still mostly British, arrived as New Zealand remained wealthy by exporting farm products to Britain. In 1953, New Zealanders were proud that a countryman, Edmund Hillary, was the first to reach the summit of Mount Everest.

From the 1890s, the economy was almost entirely based on exporting frozen meat and dairy products to Britain. In 1961, over 51% of New Zealand's exports still went to the United Kingdom.

The 1960s was a time of growing wealth for most New Zealanders. But from 1965, there were also protests. People protested for women's rights, for the environment, and against the Vietnam War. New Zealand's involvement in the Vietnam War showed a big move away from British influence. This was mainly due to New Zealand's duties under the ANZUS Treaty and worries about Communist influence in Asia. The Vietnam War was the first conflict New Zealand entered that didn't involve Britain or other Commonwealth nations (except Australia). Although the war was largely unpopular in New Zealand, it brought closer military ties between New Zealand and the United States. This lasted until 1986, when New Zealand was suspended from ANZUS because of its anti-nuclear policy.

Many New Zealanders still saw themselves as a unique part of the United Kingdom until at least the 1970s. In 1973, Britain joined the European Community. This ended its special trade agreements with New Zealand. This forced New Zealand to find new markets and rethink its national identity.

Māori Moving to Cities

Māori always had a high birth rate. But this was balanced by a high death rate until modern public health improved in the 1900s. Life expectancy grew, and the total numbers of Māori increased quickly. Many Māori served in World War II and learned how to live in modern cities. Others moved from their rural homes to cities to take jobs left by Pākehā servicemen. The move to cities was also caused by high birth rates in the early 1900s. Existing Māori farms struggled to provide enough jobs. Meanwhile, Māori culture experienced a rebirth, partly thanks to politician Āpirana Ngata. By the 1980s, 80% of the Māori population lived in cities, compared to only 20% before World War II. This move led to better pay, higher living standards, and more schooling. But it also showed problems of racism and discrimination. By the late 1960s, a Māori protest movement had started. It aimed to fight racism, promote Māori culture, and ensure the Treaty of Waitangi was honored.

Cities grew quickly across the country. In the late 1940s, city planners noted that New Zealand was "possibly the third most urbanized country in the world." Two-thirds of the population lived in cities or towns.

The Muldoon Years, 1975–1984

The country's economy suffered after the 1973 global energy crisis. New Zealand lost its biggest export market when Britain joined the European Economic Community. There was also a lot of inflation. Robert Muldoon, Prime Minister from 1975 to 1984, and his Third National Government tried to keep New Zealand as it was in the 1950s. He tried to maintain New Zealand's "cradle to the grave" welfare state, which began in 1935. His government wanted to give retirees 80% of the current wage. Critics said this would make the country go bankrupt. Muldoon also froze wages, prices, interest rates, and dividends across the country.

Muldoon's traditional and confrontational style made conflicts worse in New Zealand. The most violent example was during the 1981 Springbok Tour. In the 1984 elections, Labour promised to calm tensions. They won by a large amount.

However, Muldoon's government wasn't entirely stuck in the past. Some new things happened, like the Closer Economic Relations (CER) free-trade program with Australia. This aimed to make trade easier, starting in 1982. The goal of total free trade between the two countries was reached in 1990, five years early.

Radical Reforms of the 1980s

In 1984, the Fourth Labour Government, led by David Lange, was elected. This happened during a time of economic trouble. The new government decided to change New Zealand's economic system greatly. They reduced the government's role a lot.

The economic changes were led by Roger Douglas, the finance minister from 1984 to 1988. These changes, called Rogernomics, involved quickly removing government rules and selling public assets. Subsidies (government payments) to farmers and consumers were stopped. Financial rules were relaxed. Restrictions on foreign money were eased, and the New Zealand dollar was allowed to float freely on the world market. The tax on high incomes was cut in half. The stock market experienced a boom, which then crashed. Economic growth fell. Douglas's reforms were similar to policies at the time in Britain and the United States.

Strong criticism of Rogernomics came from the left, especially from Labour's traditional union supporters. Lange disagreed with Douglas's policies in 1987. Both men were forced out, and Labour was in disarray.

In line with the mood of the 1980s, the government supported liberal policies in social areas. This included Homosexual Law Reform, introducing 'no-fault divorce', reducing the gender pay gap, and drafting a Bill of Rights. Immigration policy was made more open, allowing more immigrants from Asia. Before this, most immigrants to New Zealand had been European. The Treaty of Waitangi Amendment Act 1985 allowed the Waitangi Tribunal to investigate claims of Treaty breaches going back to 1840 and to settle grievances.

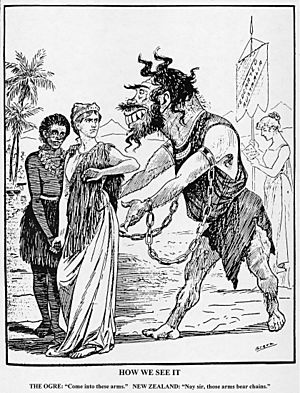

The Fourth Labour Government completely changed New Zealand's foreign policy. They made the country a nuclear-free zone. This effectively ended its military alliance with the US (ANZUS). The French intelligence service's sinking of the Rainbow Warrior ship, and the diplomatic problems that followed, helped make the anti-nuclear stance an important symbol of New Zealand's national identity.

Continuing Reforms

Voters were unhappy with how fast and far-reaching the reforms were. So, they elected a National government in 1990, led by Jim Bolger. However, the new government continued the economic reforms of the previous Labour government. Unhappy with governments not reflecting the public's mood, New Zealanders voted in 1992 and 1993 to change the electoral system to mixed-member proportional (MMP). This is a type of proportional representation. New Zealand's first MMP election was held in 1996. After the election, National returned to power in a coalition with the New Zealand First party.

After the Cold War ended in 1991, New Zealand's foreign policy focused more on its nuclear-free status and other military issues. It also focused on adjusting to free trade rules and its involvement in humanitarian, environmental, and other international matters.

21st Century

In the 21st century, international tourism was a big part of the New Zealand economy. This stopped almost completely due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The service sector (jobs like retail, hospitality, and healthcare) has generally grown. Meanwhile, traditional agricultural exports like meat, dairy, and wool have been joined by other products like fruit, wine, and timber as the economy has become more diverse.

2000s and 2010s

The Fifth Labour Government, led by Helen Clark, was formed after the December 1999 election. In power for nine years, it kept most of the previous governments' economic reforms. It limited government involvement in the economy more than earlier governments. But it put more focus on social policies and results. For example, employment law was changed to give more protection to workers. The student loan system was changed to remove interest payments for New Zealand students and graduates.

New Zealand still has strong but informal ties to Britain. Many young New Zealanders travel to Britain for their "OE" (overseas experience) because of good working visa arrangements. Even though New Zealand made immigration easier in the 1980s, Britons are still the largest group of migrants to New Zealand. This is partly because recent immigration laws favor fluent English speakers. One link to Britain remains: New Zealand's head of state, the Queen in Right of New Zealand, lives in Britain. However, British imperial honors were stopped in 1996. The governor-general has taken a more active role in representing New Zealand overseas. Appeals from the Court of Appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council were replaced by a local Supreme Court of New Zealand in 2003. There is public discussion about whether New Zealand should become a republic.

Foreign policy has been mostly independent since the mid-1980s. Under Prime Minister Clark, foreign policy focused on promoting democracy and human rights. It also aimed to strengthen the United Nations, advance anti-militarism and disarmament, and encourage free trade. She sent troops to the War in Afghanistan. But she did not send combat troops to the Iraq War, though some medical and engineering units were sent.

John Key led the National Party to victory in the November 2008. Key became Prime Minister of the Fifth National Government. This government took office at the start of the late-2000s recession. In February 2011, a major earthquake in Christchurch, the country's third-largest city, greatly affected the national economy. The government formed the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority in response. In foreign policy, Key announced the withdrawal of New Zealand Defence Force personnel from Afghanistan. He also signed the Wellington Declaration with the United States.

2020s

The COVID-19 pandemic first reached New Zealand in early 2020. It had widespread economic, social, and political effects. In March 2020, New Zealand's borders were closed to all non-residents. The government imposed a national lockdown starting March 25, 2020. All restrictions (except border controls) were lifted on June 9. The government's approach to eliminate the virus has been praised internationally. The government has a plan to deal with the expected severe economic impact from the pandemic.

The 2020 general election resulted in a victory for the Labour Party. This was the first time a single party won an outright majority since the introduction of MMP. The Labour party made a cooperation agreement with the Green Party.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern resigned in January 2023. She was replaced by Chris Hipkins. He is expected to lead the party into the 2023 general elections.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Nueva Zelanda para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Nueva Zelanda para niños

- Europeans in Oceania

- History of Oceania

- Military history of New Zealand

- Māori history

- Natural history of New Zealand

- Timeline of New Zealand history

- Timeline of the New Zealand environment

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |