New Zealand Company facts for kids

The New Zealand Company was a British company that aimed to set up new settlements in New Zealand during the first half of the 1800s. It followed ideas from Edward Gibbon Wakefield. He imagined creating a new English society in the Southern Hemisphere. In his plan, rich people would buy land, and then workers would come to help them. These workers would save money to buy their own land later.

The company started settlements in Wellington, Nelson, Wanganui and Dunedin. It also helped with settling New Plymouth and Christchurch. The first New Zealand Company began in 1825 but didn't do well. It then joined with Wakefield's New Zealand Association in 1837. The company received official permission from the King (a royal charter) in 1840. It faced money problems from 1843 and eventually closed down in 1850, with its final report in 1858.

How the Company Started and Grew

The New Zealand Company had many important people on its board. These included noblemen, members of Parliament, and a famous magazine publisher. They used their connections to push the British government to support their goals.

The company bought a lot of land from Māori. However, the agreements were often unclear. In many cases, the company resold land even though its ownership was uncertain. The company also used big, fancy, and sometimes misleading advertisements. It strongly criticized anyone who disagreed with it, especially the British government's Colonial Office and governors of New Zealand. The company also opposed the Treaty of Waitangi. This treaty made it harder for the company to get huge amounts of New Zealand land very cheaply.

The Colonial Office and New Zealand governors often criticized the company for its "trickery" and lies. Missionaries in New Zealand were also worried. They feared the company's actions would harm or even lead to the destruction of Māori people.

The company saw itself almost as a government for New Zealand. In 1845 and 1846, it suggested splitting the colony into two parts. The north would be for Māori and missionaries. The south would be a self-governing area called "New Victoria," managed by the company. The British Colonial Secretary said no to this idea.

Only about 15,500 settlers came to New Zealand through the company's plans. But three of its settlements, along with Auckland, became important cities. They also helped create the system of local government that started in 1853.

Early Attempts in 1825

The first organized attempt to settle New Zealand happened in 1825. This was when the New Zealand Company was formed in London. It was led by a rich Member of Parliament named John George Lambton.

The company asked the British Government for special trading rights for 31 years. They hoped to make a lot of money from New Zealand flax, kauri timber, whaling, and sealing. They also wanted a small military force to protect their settlements.

Even without government support, the company sent two ships to New Zealand in 1826. Captain James Herd was in charge. He was meant to look for trade opportunities and good places for settlements. On March 5, 1826, the ships Lambton and Rosanna reached Stewart Island. Herd explored it but decided it wasn't right. He then sailed north to Otago Harbour and then to Te Whanganui-a-Tara (now Wellington Harbour). Herd named this Lambton Harbour. He found a good spot for a European settlement, even though a large pā (Māori village) was already there.

The ships then sailed up the east coast, looking for trade. In January 1827, Herd explored Hokianga. There, he or the company's agent bought land from Māori in Hokianga, Manukau, and Paeroa. The price was "five muskets, fifty three pounds powder, four pair blankets, three hundred flints and four musket cartridge boxes." After a few weeks, they decided it was too expensive to export goods. The company lost £20,000 on this trip.

Wakefield's Ideas for Colonization

The failure of the 1825 project caught the eye of Edward Gibbon Wakefield. He was a young politician who was in jail at the time. Wakefield was interested in ideas about helping poor British people move to other colonies.

In 1829, Wakefield started writing about his plan for "systematic emigration" to places like Australia and New Zealand. His idea was for a company to buy land from the local people very cheaply. Then, they would sell it for a much higher price to rich settlers. The money from these sales would help pay for workers to travel to the colony. These workers would first work for the rich settlers. Eventually, they could save enough to buy their own land. But high land prices would make sure they worked for others for many years first.

After being released from prison, Wakefield joined the National Colonisation Society. His ideas quickly became the main focus of the group.

Lord Durham, who led the 1825 company, was still interested in colonization. He joined with other politicians like Charles Buller and Sir William Molesworth. They supported Wakefield's plans. In 1834, a law was passed to create the British Province of South Australia. Wakefield claimed credit for this, but he wasn't happy with how cheaply the land was sold there.

So, in late 1836, he turned his attention to New Zealand. He believed his colonization ideas could work perfectly there. He formed the New Zealand Association in May 1837. This group included many important people. Wakefield then wrote a bill (a proposed law) to make his plans happen.

This bill faced strong opposition. Officials from the Colonial Office and the Church Missionary Society were worried. They feared the "unlimited power" the company would have. They also worried about the "conquest and extermination" of Māori people. Missionaries were especially concerned that the company's plans would harm their efforts to help and civilize Māori. Wakefield had written that Māori "craved" colonization and looked up to the English as superior. He suggested that Māori chiefs would sell their land cheaply and then be "adopted" by English families to be taught new ways. The Church Missionary Society decided to use "all suitable means" to stop the company's plans.

Getting a Royal Charter

In September 1837, the New Zealand Association started talking with the 1825 New Zealand Company about joining together. The 1825 company claimed to own a million acres of New Zealand land. Lord Durham, who was in charge of that company, became the chairman of the new group.

The New Zealand Association pushed the British government hard for their plans. On December 20, 1837, they were offered a royal charter. This charter would let them manage the colony's government, laws, military, and money. But to get it, the association had to become a joint stock company with a certain amount of money invested. The government was worried because the South Australian colony, also based on Wakefield's ideas, was already in debt. They wanted shareholders to invest their own money. But the association members didn't want to invest their own money or risk stock market changes. So, they said no. On February 5, 1838, the charter offer was taken back.

Public and political opinion was still against the company. The Times newspaper made fun of Wakefield's "radical Utopia." In Parliament, a bill supporting the company was defeated. Lord Howick called it "the most monstrous proposal I ever knew made to the House."

After this defeat, the New Zealand Association decided to keep trying. On August 29, 1838, supporters from both groups formed a new company, the New Zealand Colonisation Association. This company aimed to buy and sell land, encourage emigration, and build public works. They decided to buy a ship called the Tory.

Meanwhile, the British Government was worried about the safety of Māori and the growing lawlessness among British people in New Zealand. They decided that colonization was unavoidable. In late 1838, they chose to appoint a Consul (an official representative) to New Zealand. This was a step towards Britain taking control of New Zealand. When a new Colonial Secretary, Lord Normanby, took over, he refused the New Zealand Colonisation Association's request for a royal charter.

On March 20, 1839, the company learned that the government's new bill for New Zealand would say that land could only be bought from the government. This was terrible news for the company. Their plan relied on buying land cheaply from Māori and selling it for a high profit. Wakefield urged them to act fast: "Possess yourselves of the soil and you are secure."

So, the two colonization groups formed a new organization: the New Zealand Land Company. Lord Durham was its governor. They quickly prepared the Tory ship. Colonel William Wakefield, Edward's brother, was chosen to lead the expedition. He was given £3000 worth of goods to trade for land. By May 12, 1839, when the Tory left England, the company was already advertising and selling land in New Zealand. By the end of July, all sections for their first settlement were sold, even before the Tory had arrived in New Zealand. The government had warned the company that they couldn't guarantee ownership of land bought from Māori.

The company's plan, published on May 2, explained how they would colonize. They would sell 1100 sections of land in London. Each section included one "town acre" and 100 "country acres." They would sell them for £1 per acre. The money would pay for bringing emigrants to New Zealand. Emigrants would be either rich investors or workers. Workers would have to work for the investors for several years before they could buy their own land. One out of every ten surveyed sections would be saved for Māori who had been displaced. The company would keep 25 percent of the money from land sales to cover its costs. Workers would travel for free, and those who bought land and moved could get 75 percent of their travel costs back.

1839 Expedition and Land Purchases

The Tory was the first of three New Zealand Company ships sent quickly to prepare for settlers. In August, the Cuba sailed with a team of surveyors. A month later, on September 15, 1839, the Oriental left London. It was the first of five ships hired to carry immigrants. These ships were told to meet on January 10, 1840, at Port Hardy on d'Urville Island. There, they would learn their final destination. William Wakefield was expected to have bought and surveyed land for the first settlement by then.

The company gave Wakefield detailed instructions. He was to find land with safe harbors for trade, rivers for transport, and waterfalls for power. They especially wanted land around harbors on both sides of Cook Strait. He was told to explain to Māori that the company wanted to buy land for large-scale European settlement. He also had to emphasize that one-tenth of the land in every sale would be saved for Māori. This land would become much more valuable after English settlement. The company wanted Māori land mixed with settler land, not in large separate blocks.

Wakefield arrived at Cook Strait on August 16. He spent weeks exploring the bays in the northern South Island. On September 20, the Tory crossed Cook Strait. With help from a trader named Dicky Barrett, Wakefield began offering guns, tools, and clothes to buy land from Māori near Petone. Within a week, he claimed to have secured the entire harbor and surrounding hills. From then until November, he collected signatures and marks on documents. These documents supposedly gave the company ownership of 20 million acres (8 million hectares). This was about one-third of New Zealand's land, bought for about half a penny an acre.

On October 25, he convinced 10 chiefs at Kapiti to sign a document. It said they were permanently giving up all their "rights, claims, titles and interests" to huge areas of land in both the South and North Islands. On November 8, in Queen Charlotte Sound, he got signatures from an exiled Taranaki chief, Wiremu Kīngi, and 31 others for land that was almost the same as the Kapiti deal. On November 16, three chiefs came aboard the Tory near Wanganui. They negotiated the sale of their entire district from Manawatu to Patea. The areas in each agreement were so vast that Wakefield described them using lists of place names and even degrees of latitude.

Wakefield knew that land ownership in the Port Nicholson area was complicated due to past wars. From late October, he heard rumors that Māori had sold land that didn't belong to them, but he ignored them. Problems with some purchases soon appeared. Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha told Wakefield that in their October agreement, Ngāti Toa meant for the company to have only two small areas, not millions of acres. In December, Ngāpuhi chiefs told Wakefield that the New Zealand Land Company could only claim about one square mile at Hokianga. There was nothing for them at Kaipara or Manukau Harbour. However, Wakefield did buy the Wairau Valley for £100 on December 13. This land was bought from the widow of a whaler who claimed to have bought it from Te Rauparaha. This sale later led to the 1843 Wairau Affray, where 22 English settlers and four Māori were killed.

More land was bought in Taranaki (60,000 acres in February 1840) and Wanganui (May 1840). The company explained that these new agreements were with the people living on the land, to prevent them from resisting.

By July, the company had sent 1108 working emigrants and 242 cabin passengers to New Zealand on 13 ships. More immigrant ships followed later that year.

The Treaty of Waitangi's Impact

The New Zealand Company had always expected the British Government to get involved. This happened after the Treaty of Waitangi was signed on February 6, 1840. The treaty gave control of New Zealand from Māori to the British Crown. It also said that Māori could only sell land to the Government.

Lieutenant-Governor Hobson immediately stopped all land sales. He said all existing purchases were invalid until they could be investigated. This put the New Zealand Company in a very difficult spot. They didn't have enough land for the arriving settlers, and they couldn't legally sell the land they claimed to own.

Hobson was told by the Colonial Office to set up a system where money from land sales would cover government costs and development. Some funds would also be used to send more emigrants to New Zealand. This plan showed how much Wakefield's ideas influenced things.

In April, Reverend Henry Williams was sent south by Hobson to get more signatures for the treaty. He had to wait 10 days for local chiefs to meet him. He blamed William Wakefield for their hesitation. However, on April 29, Williams reported that Port Nicholson chiefs had "unanimously" signed the treaty. William Wakefield strongly criticized the treaty and Williams. He often attacked the missionary in the company's newspaper.

Williams, in turn, criticized the company's land deals. He noted that the purchase documents for land were written in English, which Māori didn't understand. He also found that company representatives had met Māori chiefs where neither side understood the other.

Hobson became worried about the company's growing power. He heard they tried to arrest a ship captain. On March 2, they had raised the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand at Port Nicholson. They claimed to be a "colonial council" with power from local chiefs. Hobson saw this as "high treason." On May 21, 1840, he declared British control over the entire North Island. On May 23, he declared the council illegal. He sent his Colonial Secretary, Willoughby Shortland, with soldiers and police to Port Nicholson on June 30, 1840. They took down the flag. Shortland told the residents to stop their "illegal association" and obey the Crown. Hobson said the company's actions forced his hand. He then declared British control over all of New Zealand.

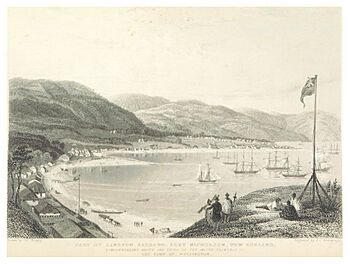

Building Wellington

William Wakefield wanted the first settlement on the southwest side of the harbor, where ships could anchor well. But Surveyor-General William Mein Smith started laying out 1100 one-acre sections in January 1840. This town, first called "Britannia," was on the flat land at Pito-one (now Petone), at the north of the harbor. The plan included wide streets and public parks. Settlers who bought a town section also bought 100 "country acres" (about 40 hectares) to grow food. Smith thought it was important to have the town and country areas close together. The Hutt Valley seemed to offer this space.

However, the chosen area was a mix of dense forest, swamp, and flax. The river often flooded, and the beach was so flat that ships had to anchor far from shore. But temporary houses were built, and wooden houses brought on ships were put together. Tents also appeared on the sand dunes. Local Māori helped with building and provided food like fish, potatoes, and pork.

Eight weeks later, in March, settlers voted to move the town. The swamps, floods, and poor anchorage at Pito-one were too much. They moved to Wakefield's preferred spot at Thorndon in Lambton Bay (later Lambton Quay). This area was named after Lord Durham.

Surveyors quickly found problems. The land chosen for the new settlement was still lived on by Māori. They were surprised to see Europeans walking through their homes, gardens, and cemeteries. Surveyors had arguments with Māori, who often refused to move. The surveyors were given weapons to continue their work.

Wakefield had bought this land during a busy week in September. He paid with iron pots, soap, guns, ammunition, axes, fish hooks, clothes, slates, pencils, umbrellas, and musical instruments. He and Barrett told local chiefs that the land would no longer be theirs once payment was made. Later, an investigation found three big problems:

- Chiefs from the Māori villages of Te Aro, Pipitea, and Kumutoto, where Thorndon was to be built, were not asked or paid.

- Te Wharepōuri, a young chief, sold land he didn't control.

- Barrett's explanation of the sale terms was very poor. Barrett later said he told them, "when they signed their names the gentlemen in England who had sent out the trade might know who were the chiefs."

Wakefield promised Māori that they would get land reserves equal to one-tenth of the area. These would be mixed among the European settlers. The reserves were meant to stay with Māori so they wouldn't sell them quickly. Jerningham Wakefield, William's nephew, hoped that mixing Māori with white settlers would help Māori change their "rude and uncivilised habits."

In November 1840, the company directors decided to name the town at Lambton Harbour after the Duke of Wellington. This was because he supported their colonization ideas. Settlers liked the name. The New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator newspaper was published in Wellington from 1840 to 1844. It was seen as speaking for the New Zealand Company.

Establishing Nelson

In April 1841, the company told the Colonial Secretary they planned a second, much larger colony. It was first going to be called Molesworth, after a supporter of Wakefield. But it was renamed Nelson, after the British admiral Horatio Nelson. The colony was planned to be 201,000 acres (81,000 km2). It would have 1000 lots, each with 150 acres of rural land, 50 acres of accommodation land, and one "town acre." Half the money from land sales would go to emigration, and about £50,000 would be company profits. Land would be sold for £301 per lot, or 30 shillings an acre.

Three ships, the Arrow, Whitby, and Will Watch, sailed to New Zealand that month. They carried surveyors and workers to prepare the land for the first settlers. However, land sales were disappointing. By early June, only 326 lots had been sold, and only 42 buyers planned to move to New Zealand.

The ships arrived at Blind Bay (now Tasman Bay). The expedition leaders looked for suitable land and chose the site of present-day Nelson. This area was described as marshy land covered with scrub and fern. In a meeting with local Māori, expedition leader Arthur Wakefield claimed to have gotten their agreement for the 1839 land "purchases" by William Wakefield. He gave them "presents" like axes, a gun, gunpowder, blankets, biscuits, and pipes. By January 1842, the advance group had built over 100 huts for the first settlers. A month later, the town had 500 people and farm animals. But the company still hadn't found or bought the rural land that buyers had paid for.

The search for this remaining 200,000 acres (81,000 km2) led to the Wairau Affray on June 17, 1843. This event, also called the "Wairau Massacre," resulted in 22 Europeans and four Māori dying in a fight over land in the Wairau Valley. Arthur Wakefield claimed to have bought the land from a whaler's widow, who said she bought it from chief Te Rauparaha. The chief denied selling it. Governor Robert FitzRoy investigated and blamed the New Zealand Company representatives.

The New Zealand Company also tried to get German emigrants. They appointed an agent in Bremen. In September 1841, they tried to sell the Chatham Islands to a German company for £10,000. But the British Government stopped this, saying the islands were part of New Zealand. German settlers would be treated as foreigners. A group of German migrants on the St Pauli went to Nelson instead.

Government Steps In

The New Zealand Company started its colonization without the British government's approval. In May 1839, a government official warned the company that land titles bought from Māori might not be recognized. In January and February 1840, Governor George Gipps of New South Wales and Hobson in New Zealand announced that all land bought from Māori had to be confirmed by the government. Any future direct purchases from Māori were invalid.

Gipps introduced a bill in May 1840 to investigate all land bought from Māori. The bill also said that Māori only owned land they lived on or farmed. All other land was considered "waste" and belonged to the Crown. The law, passed on August 4, said no land purchase could be larger than four square miles (2560 acres). The New Zealand Company had already claimed to buy two million acres (8,000 km2), some of which they had sold to settlers. When this news reached Wellington in August, it caused panic. Many settlers prepared to leave for Valparaíso, Chile. To calm the settlers, a group went to Sydney to meet Gipps. In December, they returned with news that Gipps would confirm their ownership of 110,000 acres in Wellington. This was subject to conditions, including that the land be in one continuous block, and that reserves be made for Māori and for public use.

In late 1840, New Zealand Company Secretary Charles Buller asked the Colonial Office for help. Over the next month, the two sides negotiated an agreement. Colonial Secretary Lord John Russell agreed to offer a royal charter for 40 years. This would allow the company to buy, sell, settle, and farm lands in New Zealand. The Colonial Land and Emigration Commission would oversee the company's activities. Russell also agreed to give the company four acres of land for every pound it had spent on colonization. In return, the company would give up its claim to 20 million acres. He also promised the company a discount on buying 50,000 acres from the government.

The company started giving the Colonial Office figures for its total spending. This included money paid to the 1825 company and the 1838 New Zealand Colonisation Company, as well as the cost of the Tory ship. Spending on advertisements, salaries, and food and transport for emigrants was also included. The cost of goods, including firearms, used to buy land was added too. By May 1841, it was calculated that the company was entitled to 531,929 acres, with possibly another 400,000 to 500,000 acres to come. In May, Russell agreed to give the company a 20 percent discount on 50,000 acres they wanted to buy in New Plymouth and Nelson.

Hobson visited the Wellington area for the first time in August 1841. He heard complaints directly from Māori that they had never sold their land. Hobson promised that their unsold villages and farms would be protected. But within days, he gave William Wakefield a list, dated September 1, of 110,000 acres at Port Nicholson, Porirua, and Manawatu; 50,000 acres at Wanganui; and 50,000 acres (later 60,000 acres) at New Plymouth. The government would not claim these areas. In a secret note, Hobson promised that the government would approve any fair agreement to get Māori living in these areas to give up their homes, as long as no force was used. FitzRoy later pressured Te Aro Māori to accept £300 for valuable land in Wellington that they had never been paid for. He told them their land was almost worthless.

New Zealand Land Commission

In May 1842, William Spain, an independent Land Commissioner, began his official investigation into the New Zealand Company's land claims. Spain quickly found that Māori strongly disputed the company's purchases in the Port Nicholson, Wanganui, and New Plymouth areas. In Wellington, several important chiefs did not take part in the hearings. Those who agreed to "sell" the land gave two main reasons: European weapons and settlement would protect them from enemies, and they knew a European settlement would bring them wealth through trade and jobs. Some sales were also part of complex power struggles among Māori tribes.

The company and the Colonial Office argued about who should pay if Māori needed to be compensated for land they hadn't sold. The Colonial Office said its 1840 agreement assumed the company's claims were valid. The company didn't want to have to prove that Māori understood the contracts and had the right to sell. Company representatives in London tried to challenge Spain's investigation and told William Wakefield not to answer it.

Spain decided how much land the company would get after each investigation. The company was given 151,000 acres (61,155 hectares) at Nelson after paying £800, but their claim on the Wairau valley was rejected. At Wellington, the company was ordered to pay £1500 to complete the Port Nicholson agreement and was then given 71,900 acres (29,100 hectares). Spain refused to grant any land at Porirua and promised only 100 acres (40.5 hectares) at Manawatu. He awarded 40,000 acres (16,200 hectares) at Wanganui and 60,000 acres (24,300 hectares) at Taranaki. In London, the Colonial Office had already decided that land claimed by settlers but not awarded to them by the Land Claims Commission should go to the Crown, not back to the Māori owners.

Spain's decision about Taranaki led to his downfall. He had based his decision on information from William Wakefield that much of the Taranaki region had few Māori living there at the time of purchase. Many local Te Āti Awa people had moved away or been enslaved after wars in the 1820s, but many were now returning. Spain ruled that Te Āti Awa had lost the land, and the company's purchase from the few remaining residents was valid. Tensions were very high between settlers and Māori in Taranaki. Governor FitzRoy sailed to New Plymouth in August 1844. He reversed Spain's decision. Instead of 60,000 acres in Taranaki, the company would get only 3800 acres, where settlers were already located. This decision angered settlers. FitzRoy later wrote that giving the company land they hadn't bought would cause bloodshed. Spain was furious, and the Governor demanded his resignation.

Spain's award in Wanganui also wasn't fully delivered. Some chiefs refused to sell, no matter how much compensation was offered. Spain offered to return four sections of land to Māori along with £1000. But when they still refused, Spain told them their refusal wouldn't stop the land from going to the settlers.

More Settlements

The New Zealand Company also started a settlement at Wanganui in 1840. This was mainly a place for settlers who couldn't find land in Wellington. A traveler at the time called Wanganui "one of the unhealthy, mushroom settlements" created by the company to deal with angry land buyers. The Wanganui settlement had problems when settlers arrived to find Māori on the land, saying it hadn't been sold. The company also sent surveyors down the east coast of the South Island to look for more sites. They met a small French colony at Akaroa.

The company also helped with the settlement of New Plymouth in 1841. It sold 60,000 acres to the Plymouth Company. The Plymouth Company's surveyor chose Taranaki for the settlement in January 1841. The Plymouth Company had money problems and joined with the New Zealand Company on May 10, 1841.

In July 1843, the New Zealand Company announced a plan to sell 120,550 acres (48,000 hectares) for a new settlement called New Edinburgh. The location was still undecided. An office was set up in Edinburgh to attract Scottish emigrants. In January 1844, a 400,000-acre (160,000-hectare) area was chosen around the harbor at Otago. The company worked with the Free Church of Scotland to sell land. The first settlers sailed for what became Dunedin in late November 1847.

A month later, Gibbon Wakefield started promoting a plan he had suggested in 1843: a Church of England settlement. The company first hoped to put this settlement in the Wairarapa region in the lower North Island. But local Māori refused to sell. So, their surveyor looked at Port Cooper (Lyttelton Harbour) on the east coast of the South Island and chose that spot. Land was bought from 40 members of the Ngāi Tahu tribe in June 1848. The colonization efforts were then taken over by the Canterbury Association, Gibbon Wakefield's new project. The New Zealand Company became a quiet partner, mostly providing the initial money. The first group of 1512 Canterbury settlers sailed on September 8, 1850.

Money Problems and Closing Down

The New Zealand Company started having money problems from mid-1843. This was for two main reasons. The company planned to buy land cheaply and sell it for a lot more. They hoped that higher land prices would attract wealthy colonists. The profits from land sales were supposed to pay for free travel for working-class colonists and for public works like churches and schools. For this plan to work, there needed to be the right number of workers for the rich landowners. But this balance was never achieved. There were always more workers, whose travel was heavily paid for by the company, than rich landowners.

The second big problem was that many people bought land for speculation. This means they bought it hoping its value would go up, with no plan to move to New Zealand and develop the land. This meant the new colonies didn't have enough employers, and therefore not enough work for the working class. From the start, the New Zealand Company had to be the main employer in the new colonies. This cost the company a lot of money. They repeatedly asked the British government for financial help. In late 1846, the company accepted an offer for a £236,000 loan. This loan came with strict rules and government oversight.

In June 1850, the company admitted that land sales in Wellington, Nelson, and New Plymouth were still poor. Their land sales for the year ending April 1849 were only £6,266. With little hope of making a profit, the company gave up its charter. A report concluded that the company's losses were "mainly attributable to their own proceedings, characterised as they were in many respects by rashness and maladministration."

Gibbon Wakefield, who had left the company in anger after its 1846 deal with the government, remained firm. In 1852, he said that if the company had been left alone, it would have made a profit and there would now be 200,000 settlers in New Zealand.

The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 said that a quarter of the money from land sales (from land the New Zealand Company had bought) would go to pay off its debt.

In its final report in May 1858, the company admitted it had made mistakes. But it also said that the communities they had started were now growing well. They looked forward to the day when "New Zealand shall take her place as the offspring and counterpart of her Parent Isle ... the Britain of the Southern Hemisphere."

Images for kids

See also

- New Zealand Company ships

- Canterbury Association

- Otago Association

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |