Wairau Affray facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Wairau Affray |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the New Zealand Wars | |||

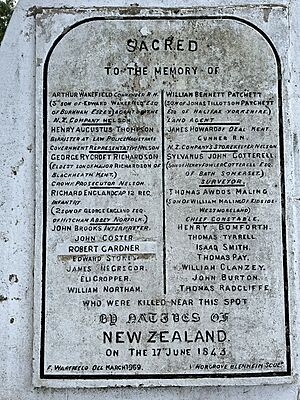

Wairau Memorial in Tuamarina cemetery

|

|||

| Date | 17 June 1843 | ||

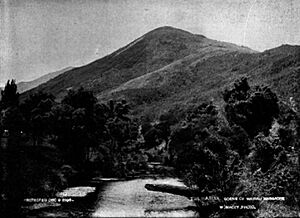

| Location |

Tuamarina, Wairau, New Zealand

41°25′40.5″S 173°57′32.9″E / 41.427917°S 173.959139°E |

||

| Caused by | Possession of lands and estates | ||

| Goals | The arrest of Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata for arson | ||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

|

|||

The Wairau Affray happened on 17 June 1843. It is also known as the Wairau Massacre or Wairau Incident. This event was the first big clash between British settlers and Māori in New Zealand. It happened after the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. It was also the only major fight of its kind in the South Island.

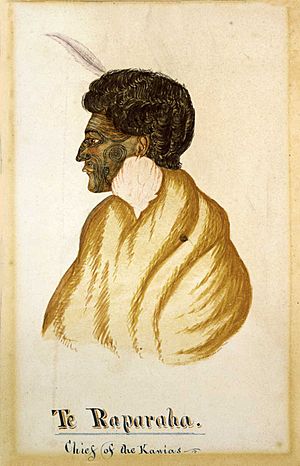

The conflict began when a group of European settlers tried to arrest two important Ngāti Toa chiefs, Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata. The settlers were led by a magistrate and a person from the New Zealand Company. They believed they owned land in the Wairau Valley in Marlborough. However, the Māori chiefs said the land was theirs.

Fighting broke out between the two groups. Twenty-two British settlers were killed, including nine after they had given up. Four Māori people were also killed. One of them was Te Rongo, who was Te Rangihaeata's wife. This event made settlers worried about more fighting with Māori. It also created a big challenge for Governor Robert FitzRoy, who arrived in New Zealand six months later. FitzRoy looked into the incident. He decided that Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata were not to blame. Many settlers and the New Zealand Company were very unhappy with his decision. Years later, in 1944, an investigation found that the Wairau Valley land had not been sold legally. The government decided to pay money to the Rangitāne iwi (Māori tribe). They were the original owners of the land.

Contents

Why the Conflict Started

The New Zealand Company started a settlement near Nelson in the South Island in 1840. They planned to buy a large amount of land, about 200,000 acres (800 square kilometers). But even as they sold land in England, their agents in New Zealand struggled to find and buy enough land from local Māori.

Settlers began buying large areas of land directly from Māori. They often did this without asking the new government. Sometimes, they bought land from people who did not truly own it. This caused problems and arguments between the settlers and Māori.

The Disputed Land

In January 1843, Captain Arthur Wakefield was sent by the New Zealand Company to lead settlers to Nelson. He was the brother of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, a main leader of the company. Arthur wrote that he found the land they needed at Wairau, about 25 kilometers from Nelson.

He claimed he had a paper (a deed) for the land. He said he bought it in 1839 from the wife of a whaling captain, John William Dundas Blenkinsop. This woman, Te Rongo, was later killed in the conflict.

Wakefield wrote in March 1843 that he expected "some difficulty with the natives." The problem was simple: Chiefs Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata, and their Ngāti Toa relatives, believed they owned the land. They said they had not been paid for it. They had controlled the area since the early 1830s. This was after they defeated the previous tribe, the Rangitāne iwi.

Warnings and Disagreements

The Ngāti Toa believed that under British law, they were the true owners. They had not sold the land. They asked the surveyors to stop working until the land claim was checked. This check was being done by Land Commissioner William Spain.

In January 1843, Nohorua, Te Rauparaha's older brother, went to Nelson. He led other chiefs to protest against British activity in the Wairau Plains. Two months later, Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata came to Nelson. They asked for the land ownership issue to be left to William Spain. Spain was based in Wellington and was already checking all the land purchases claimed by the New Zealand Company.

Spain later wrote that Arthur Wakefield tried to pay the chiefs for Wairau during that visit. But the chiefs "positively refused to sell it." They told him they would "never consent to part from it."

Arthur Wakefield did not want to wait for Spain's check. He told Te Rauparaha that if Māori stopped the company's surveyors, he would bring 300 police to arrest him. Wakefield then sent three groups of surveyors to the land. Local Māori quickly warned them to leave. They broke the surveyors' tools but did not hurt the men.

Te Rauparaha and Nohorua wrote to Spain on 12 May. They urgently asked him to come to the South Island to settle the company's claim to Wairau. Spain replied that he would come after finishing his work in Wellington. A month later, Spain still had not arrived. Te Rauparaha led a group to Wairau. They destroyed all the surveyors' equipment and shelters. These shelters were made from plants found on the land. They burned down small huts that held surveying tools. The surveyors were gathered up and sent back to Nelson without harm.

The Day of the Clash

The Nelson Examiner newspaper reported "Outrages by the Maori at Wairoo." Because of this, Wakefield gathered a group of men. This group included Police Magistrate Henry Augustus Thompson and about 50 other men who were ordered to join. Thompson issued a warrant to arrest Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata for burning the huts. Wakefield called the chiefs "traveling bullies."

Thompson took control of a government ship that was in Nelson. On the morning of 17 June, the group, which had grown to about 50 to 60 men, approached the Māori camp. The New Zealand Company's storekeeper gave the British men weapons like swords and pistols.

At a path across a stream, Te Rauparaha stood with about 90 warriors, as well as women and children. He allowed Thompson and five other men to come closer. But he asked the rest of the British group to stay on their side of the stream.

Fighting Breaks Out

Thompson refused to shake hands with Te Rauparaha. He said he had come to arrest him, not about the land, but for burning the huts. Te Rauparaha replied that the huts were made from plants on his own land. He said he had burned his own property. Thompson insisted on arresting Te Rauparaha. He showed handcuffs and told his men to get ready to cross the stream.

As the British began to cross, one of them fired a shot by accident. Te Rangihaeata's wife, Te Rongo, was killed in one of the first shots. This caused gunfire from both sides. The British quickly went back across the stream and up a hill. They were still being shot at by the Ngāti Toa. Several people from both sides were killed.

Te Rauparaha ordered the Ngāti Toa warriors to cross the stream and chase them. The British who had not escaped were quickly caught. Wakefield called for a stop to the fighting and gave up. Thompson, and ten others also surrendered. The Māori immediately killed two of the British.

Te Rangihaeata demanded utu (revenge) for the death of his wife, Te Rongo. The Māori killed all the remaining captives. This included Thompson, Captain Wakefield, and others. In total, four Māori died and three were hurt. The British lost 22 dead and five wounded.

Te Rongo was a chief from the Ngāti Mutunga tribe. Her first husband was Captain John Blenkinsop, who made the land deed that Wakefield bought.

Some survivors ran back to Nelson to get help. A search party, including sailors, returned to Wairau. They buried the bodies where they were found. Thirteen were put in one grave, and the rest were buried in smaller groups. A historian named Michael Belgrave said that the British attempt to survey the land was against the law and caused the disaster.

What Happened Next?

News of the "massacre" reached England. The New Zealand Company almost failed because of reports that "British citizens were murdered by barbarous natives." Land sales almost stopped. It became clear that the company had not been honest about how it bought land. Reports in local newspapers were also not accurate.

In the Nelson area, settlers became very worried. One group complained to the government. They said those who died were doing their "duty as magistrates and British subjects." They believed the Māori who killed them were "murderers."

Governor FitzRoy's Decision

In early 1844, Governor Robert FitzRoy arrived in New Zealand. He visited Wellington and Nelson to calm the anger between Māori and British. He knew there were many different stories about what happened at Wairau. He could not easily decide who was wrong.

He immediately criticized the New Zealand Company and a newspaper for being aggressive towards Māori. He warned that "not an acre, not an inch of land belonging to the natives shall be touched without their consent."

He also asked the magistrates who had ordered the arrests of the Māori chiefs to resign. FitzRoy explained, "Arson is burning another man's house. It is not arson to burn your own house. The natives had never sold the Wairau. The hut which was burned was built on ground which belonged to the natives. So, no arson was committed, and the arrest warrant was illegal."

From Nelson, FitzRoy sailed to Waikanae in the North Island. There, he held his own investigation into the incident. He told a meeting of 500 Māori: "When I first heard of the Wairau massacre... I was very angry... My first thought was to get revenge for the deaths of my friends, and the other Pākehā (European settlers) who had been killed. I thought of bringing many warships... with many soldiers. If I had done so, you would have been destroyed. But when I thought about it, I saw that the Pakeha had been very much to blame first. So I decided to come and find out all the facts and see who was really wrong."

Te Rauparaha, Te Rangihaeata, and other Māori told their side of the story. FitzRoy took notes and asked questions. He ended the meeting by saying his decision: "First, the white men were wrong. They had no right to survey the land... they had no right to build houses on the land. Since they were wrong first, I will not get revenge for their deaths."

But FitzRoy also told the chiefs they had done "a horrible crime, in murdering men who had given up. White men never kill their prisoners." He asked British and Māori to live peacefully, with no more bloodshed.

Settlers and the New Zealand Company were very angry about the Governor's decision. But FitzRoy's choice was smart and practical. Māori outnumbered settlers greatly. Many iwi (tribes) had been collecting weapons for years. They could have destroyed settlements in Wellington and Nelson. FitzRoy knew the British Government would likely not send soldiers to fight the Māori or protect the settlers.

FitzRoy's report was supported by Colonial Secretary Lord Stanley. He said the actions of Thompson and Wakefield were "clearly illegal, unfair, and unwise." He added that their deaths happened as a "natural and immediate result." William Williams, a leading missionary, also blamed "our countrymen, who began with much carelessness and gave much reason for the natives to be angry."

Long-Term Effects

The Wairau Affray and FitzRoy's reaction led to many events that still affect New Zealand today. It immediately worried settlers in New Plymouth. They had bought land in similar ways to Wairau and were not sure if they truly owned it. FitzRoy became very unpopular and was replaced by Governor George Grey.

After the conflict, Te Rauparaha was captured in 1846. This was for organizing an uprising in the Hutt Valley. He was held on a ship in Auckland without any charges. Some people believe this arrest was a delayed punishment for the Wairau killings. The Ngāti Toa iwi sold the Wairau land while Te Rauparaha was held captive. After he was released, Te Rauparaha returned to the Wairau Valley. He was there during the 1848 earthquake.

This rohe (area) has been part of a long but successful land claim by the original Rangitāne iwi. They were forced out of the area in the 1820s by Te Rauparaha's tribe. The Rangitāne iwi are now recognized as the tangata whenua (people of the land). In 1944, a government investigation confirmed that the Wairau land had never been legally sold to the settlers. The New Zealand government is expected to pay about $2 million in compensation.

Remembering the Wairau Affray

In 1869, the Nelson community built a memorial at Tuamarina Cemetery. It remembers the European people who died in the incident. Their names and jobs are listed on the memorial. The plaque had to be replaced soon after because of many spelling mistakes.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |