New Zealand Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids New Zealand WarsNgā pakanga o Aotearoa |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Memorial in the Auckland War Memorial Museum for all who died in the New Zealand Wars. "Kia mate toa" translates as "fight unto death" or "be strong in death", and is the motto of the Otago and Southland Regiment of the New Zealand Army. The flags are the Union Jack and the flag of the Māori defenders of Gate Pā. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Māori iwi | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 18,000 (peak deployment) | 5,000 (peak deployment) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 745 killed (including civilians) | 2,154 killed (including civilians) | ||||||||

The New Zealand Wars were a series of conflicts that happened in New Zealand between 1845 and 1872. They were fought between the New Zealand government (and some Māori allies) and other Māori groups (sometimes with European settlers who sided with them). These wars were also known as the Land Wars or the Māori Wars. In the Māori language, they are called Ngā pakanga o Aotearoa, meaning "the great New Zealand wars," or Te riri Pākehā, meaning "the white man's anger."

At first, these conflicts were small and local. They started because of disagreements over land sales. However, from 1860, the wars grew much bigger. The government believed Māori were uniting to stop land sales and challenge British rule. Thousands of British soldiers were brought in to fight the Kīngitanga (Māori King) movement. The government also wanted to take land for British settlers. Later, fighting also involved the Hauhau movement, a part of the Pai Mārire religion. This group strongly opposed the taking of Māori land and wanted to strengthen Māori identity.

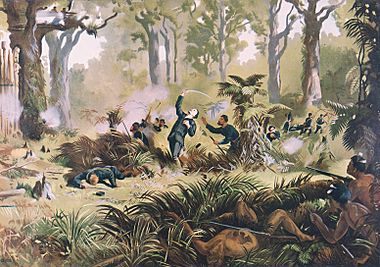

During the busiest time of the wars in the 1860s, about 18,000 British soldiers fought against roughly 4,000 Māori warriors. Even though they were greatly outnumbered, Māori used clever tactics. They built special bunkers to protect against artillery and used well-placed pā (fortified villages). These pā helped them block enemy advances and cause heavy losses, but Māori could also leave them quickly without losing many fighters. Both sides used guerrilla tactics later in the wars, often fighting in thick bush. Around 1,800 Māori and 800 Europeans died during the Taranaki and Waikato campaigns. The total number of Māori deaths across all the wars might have been more than 2,100.

The first violence over land happened in the Wairau Valley in the South Island in June 1843. But serious fighting involving British troops began in Taranaki in March 1860. The war between the government and Kīngitanga Māori spread across the North Island. The biggest fight was the invasion of the Waikato in 1863–1864. The wars ended with the pursuits of Riwha Tītokowaru in Taranaki (1868–1869) and Chief Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki on the east coast (1868–1872).

At first, British soldiers fought Māori. But the New Zealand government also created its own army. This included local militia, volunteer groups, special Forest Rangers, and kūpapa (Māori who supported the government). About 2,500 men from Australia joined the New Zealand militia. The government also passed laws to imprison Māori opponents and take large areas of land in the North Island. This land was then sold to settlers, and the money helped pay for the wars. These harsh actions made Māori resistance even stronger.

Contents

Why the Wars Started

The 1840 English version of the Treaty of Waitangi promised that Māori iwi (tribes) would keep their lands, forests, fishing areas, and other taonga (treasures). In return, Māori would become British subjects, sell land only to the government, and give up their rule to the British Crown. However, in the Māori language version of the Treaty, the word for "sovereignty" was translated as kawanatanga. This was a new word meaning "governance," which led to big disagreements about what the Treaty really meant. Some Māori signed to bring peace and end the Musket Wars (1807–1842) between tribes. Others, like the Tūhoe people, wanted to keep their tino rangatiratanga (full authority and control).

Before the Treaty, land sales happened directly between Māori and Europeans. Early on, Māori often wanted to trade with Europeans. British and French missionaries set up stations and received land from iwi for homes, schools, churches, and farms.

Traders, businessmen from Sydney, and the New Zealand Company bought large areas of land before 1840. The Treaty of Waitangi included the government's right to be the first to buy land (called the right of pre-emption). The New Zealand government, pushed by European settlers, tried to speed up land sales to create farms. This was met with resistance from the Kīngitanga (Māori King) movement, which started in the 1850s. This movement opposed more European settlement on their lands.

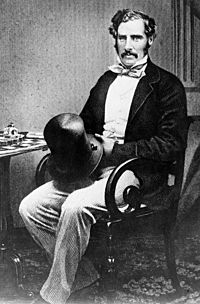

Governor Thomas Gore Browne bought a disputed piece of land at Waitara in 1859. This action put the government on a path to conflict with the Kīngitanga movement. The government saw the Kīngitanga's reaction as a challenge to the Crown's power. Governor Gore Browne brought 3,500 British soldiers from Australia to stop this challenge. Within four years, 9,000 British troops arrived in New Zealand. They were helped by over 4,000 colonial and kūpapa (pro-government Māori) fighters. The government wanted a clear victory over the "rebel" Māori.

From 1865, the government used a harsh policy of taking land. This took away Māori people's way of life and made them even angrier. This fueled more conflict in Taranaki (1863–1866) and on the east coast (1865–1866).

Key Conflicts and Campaigns

The New Zealand Wars happened over a long time, and their causes and results varied a lot. In the 1840s, Māori were still the main power. But by the 1860s, there were many more settlers and resources. From about 1862, British troops arrived in much larger numbers. Governor George Grey called for them for his Waikato invasion. By March 1864, the total number of troops reached about 14,000. This included 9,000 British soldiers, over 4,000 colonial troops, and a few hundred kūpapa.

Wairau Valley Clash (1843)

The first armed conflict between Māori and European settlers happened on 17 June 1843 in the Wairau Valley. This was in the north of the South Island. The fight started when settlers, led by someone from the New Zealand Company, tried to clear Māori off land. The company had a false land deed. The settlers also tried to arrest Ngāti Toa chiefs Te Rauparaha and Te Rangihaeata. Fighting broke out, and 22 Europeans died, along with four to six Māori. Nine Europeans were killed after being captured. In early 1844, the new governor, Robert FitzRoy, investigated. He said the settlers were at fault. This event was the only armed conflict of the New Zealand Wars to happen in the South Island.

Northern War (1845–1846)

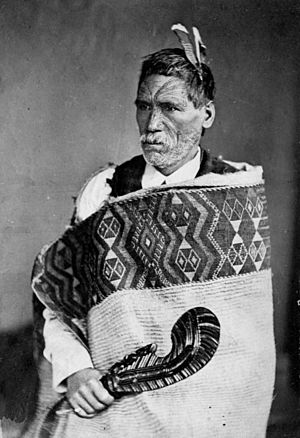

The Flagstaff War took place in the far north of New Zealand, around the Bay of Islands. It happened between March 1845 and January 1846. In 1845, George Grey became governor. At this time, Hōne Heke challenged British rule. He started by cutting down the flagstaff on Flagstaff Hill at Kororāreka. This flagstaff used to fly the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand. But now it had the Union Jack, which showed Heke and his ally Te Ruki Kawiti's unhappiness with changes after the Treaty of Waitangi.

Heke had several complaints about the Treaty of Waitangi. While land purchases by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) were debated, Heke's rebellion was against the colonial forces. CMS missionaries tried to convince Heke to stop fighting. Most of the Ngāpuhi tribe, led by Tāmati Wāka Nene, sided with the government. The British forces were small and not well-led, and they were defeated at the Battle of Ōhaeawai. Governor Grey, with more money and troops armed with powerful cannons, attacked and took Kawiti's fort at Ruapekapeka. This forced Kawiti to retreat. Heke's confidence dropped after he was wounded fighting Tāmati Wāka Nene's warriors. He also realized the British had far more resources, including some Pākehā Māori who supported them.

After the Battle of Ruapekapeka, Heke and Kawiti wanted peace. They asked Tāmati Wāka Nene to help them talk with Governor Grey. Grey agreed with Nene that Heke and Kawiti should not be punished. The fighting in the north ended, and no Ngāpuhi land was taken.

Hutt Valley and Wanganui Conflicts (1846–1848)

The Hutt Valley campaign in 1846 followed the Wairau Affray. The reasons were similar: questionable land purchases by the New Zealand Company and settlers wanting to move onto land before ownership disputes were settled. Key events included a Māori attack on a British army post at Boulcott's Farm on 16 May 1846. Eight British soldiers and about two Māori died. Another was the Battle of Battle Hill from 6–13 August. British troops, local militia, and kūpapa chased a Ngāti Toa force led by chief Te Rangihaeata through thick bush. Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha was also arrested during this time and held without charge for two years.

This fighting made settlers in nearby Wanganui very worried. The town was given a strong military force. In April 1847, a minor Wanganui Māori chief was accidentally shot. This led to a violent attack on a settler family. When the attackers were caught and hanged, a large raid was launched on the town. Homes were looted and burned, and animals were stolen. Māori surrounded the town before attacking it in July 1847. A peace agreement was reached in early 1848.

First Taranaki War (1860–1861)

The main reason for the First Taranaki War was a disputed land sale at Waitara. The Crown wanted to buy 240 hectares of land. But the main chief of the Te Āti Awa tribe, Wiremu Kīngi, said no. Local Māori also had a "solemn contract" not to sell. Governor Browne knew all this but still accepted the purchase. He tried to take the land, expecting it would lead to war. He wanted to show the British had full power, as they believed they gained from the Treaty of Waitangi. Fighting began on 17 March 1860. More than 3,500 British soldiers from Australia, along with volunteers and militia, fought against Māori forces. Māori numbers varied between a few hundred and about 1,500. The Victorian government sent its ship HMVS Victoria to bring men, fire cannons from the coast, and patrol the sea. It also kept supply routes open between Auckland and New Plymouth. After many battles, the war ended in a ceasefire. Neither side fully accepted the other's peace terms. About 238 British and colonial soldiers died, and around 200 Māori. Many at the time felt the British had suffered a humiliating result. Historians still debate who won. Historian James Belich believes Māori stopped the British from fully taking control, so they were victorious. However, he also says this Māori victory led to the invasion of the Waikato.

Invasion of the Waikato (1863–1864)

Governor Browne started planning a campaign to destroy the Kīngitanga stronghold in Waikato after the First Taranaki War. These plans were paused in December 1861 when Sir George Grey replaced him. But Grey restarted the invasion plans in June 1863. He convinced the Colonial Office in London to send over 10,000 British soldiers to New Zealand. General Sir Duncan Cameron was chosen to lead the campaign. Cameron used soldiers to build the 18 km long Great South Road to the Kīngitanga border. On 9 July 1863, Grey ordered all Māori living between Auckland and the Waikato to swear loyalty to Queen Victoria. If they refused, they would be sent south of the Waikato River. When they refused, the army crossed into Kīngitanga land and set up a camp. Many small attacks on his supply lines forced Cameron to build many forts and strongholds. Cameron eventually had 14,000 British and colonial soldiers. This included 2,500 volunteers from Australia who joined the Waikato militia. He also had steamers and armored boats for the Waikato River. They fought against about 4,000 Māori.

Cameron and the Kīngitanga forces fought several big battles, including the Battle of Rangiriri and a three-day siege at Orakau. The British captured the Kīngitanga capital of Ngāruawāhia in December 1863. The Waikato conquest was finished in April 1864. The Waikato campaign cost the lives of 700 British and colonial soldiers and about 1,000 Māori.

The Kīngitanga Māori retreated into the rugged central North Island. In 1865, the New Zealand Government took about 12,000 km2 of Māori land (4% of New Zealand's land area) for white settlement. This action quickly led to the Second Taranaki War.

Second Taranaki War (1863–1866)

Between 1863 and 1866, fighting restarted between Māori and the New Zealand Government in Taranaki. This is sometimes called the Second Taranaki War. This conflict happened at the same time as wars in Waikato and Tauranga. It was caused by several things: Māori were still angry about the land sale at Waitara in 1860, and the government was slow to fix the problem. Also, the government started a large-scale land confiscation policy in late 1863. The rise of the Hauhau movement, an extreme part of the Pai Marire religion, also played a role. This movement strongly opposed the loss of Māori land and wanted to strengthen Māori identity. The Hauhau movement helped unite Taranaki Māori when they didn't have single commanders.

The way of fighting changed after 1863. In the 1860–1861 conflict, Māori had taken fixed positions and openly challenged the army. From 1863, the army, with more troops and heavy cannons, systematically took Māori land by driving out the people. They used a "scorched earth" strategy, destroying Māori villages and farms. They attacked villages, whether they were fighting or not. Historian Brian Dalton noted: "The goal was no longer to conquer land, but to cause the most 'punishment' to the enemy. This often led to much brutality, burning of undefended villages, and widespread looting, where loyal Māori often suffered." As the troops moved forward, the government built more forts. Behind these, settlers built homes and farms. This led to the gradual taking of almost 4,000 km2 of land. Little difference was made between the land of loyal or rebel Māori owners. The result of the fighting in Taranaki between 1860 and 1869 was a series of forced land takings from Taranaki tribes. These tribes were all labeled as being in rebellion against the government.

East Cape War (1865–1866)

Fighting on the east coast began in April 1865. Like the Second Taranaki War, it started because Māori were angry about the government taking their land. It was also fueled by the spread of the radical Pai Marire religion. This religion arrived on the east coast from Taranaki in early 1865. The killing of missionary Carl Volkner by Pai Mārire (or Hauhau) followers at Opotiki on 2 March 1865 made settlers fear more violence. Later that year, the New Zealand government launched a long expedition to find Volkner's killers and stop the movement's influence. Growing tensions between Pai Mārire followers and more traditional Māori led to wars between and within Māori iwi. The government armed kūpapa (pro-government Māori) to try and destroy the movement.

Major battles included a cavalry and artillery attack on Te Tarata pā near Opotiki in October 1865, where about 35 Māori were killed. Another was the seven-day siege of Waerenga-a-Hika in November 1865. The government took northern parts of Urewera land in January 1866. They did this to break down what they thought was Māori support for Volkner's killers. They took more land in Hawke's Bay a year later after defeating a Māori group they saw as a threat to the settlement of Napier.

Titokowaru's War (1868–1869)

War started again in Taranaki in June 1868. Riwha Titokowaru, chief of Ngāruahine, reacted to the continued surveying and settlement of confiscated land. He launched well-planned and effective attacks on settlers and government troops. He wanted to stop the occupation of Māori land. These attacks happened at the same time as a violent raid on a European settlement on the East Coast by Te Kooti. The attacks shattered what European colonists thought was a new era of peace. They created fears of a "general uprising of hostile Māoris."

Titokowaru had fought in the Second Taranaki War. He was the most skilled West Coast Māori warrior. He also acted as a priest and prophet of the extreme Hauhau movement. Titokowaru's forces were small and at first outnumbered 12 to one by government troops. But their fierce attacks scared settlers. Many militia volunteers resigned or ran away. This led to most government troops leaving South Taranaki. Titokowaru gained control of almost all land between New Plymouth and Wanganui. Titokowaru provided the strategy and leadership that had been missing among tribes in the Second Taranaki War. His forces never lost a battle during their intense campaign. However, they mysteriously left a strong position at Tauranga-ika Pā, and Titokowaru's army quickly began to break up.

Once Titokowaru was defeated and the East Coast threat reduced, the taking of Māori land and the political control over Māori continued even faster.

Te Kooti's War (1868–1872)

Te Kooti's War was fought in the East Coast region and across the heavily forested central North Island and Bay of Plenty. It was between government forces and followers of the spiritual leader Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki. The conflict began when Te Kooti returned to New Zealand. He had escaped from the Chatham Islands after two years of being held there. He escaped with almost 200 Māori prisoners of war and their families. Te Kooti, who had been held without trial, asked to be left in peace with his followers. But within two weeks, they were being chased by militia, government troops, and Māori volunteers. This chase turned into a four-year guerrilla war. It involved more than 30 expeditions by colonial and Māori troops against Te Kooti's shrinking number of warriors.

At first, Te Kooti fought defensively against the chasing government forces. But from November 1868, he went on the attack. This started with the Poverty Bay massacre. It was a well-planned, quick attack on selected European settlers and Māori opponents in the Matawhero district. Fifty-one men, women, and children were killed, and their homes were burned. This attack led to another strong pursuit by government forces. This included a siege at Ngatapa pā. It ended in a bloody way: Te Kooti escaped, but Māori forces loyal to the government caught and killed over 130 of his supporters, as well as prisoners he had taken earlier. Te Kooti was unhappy with the Māori King Movement's unwillingness to keep fighting against European invasion and land taking. He offered Māori a vision of hope from the Old Testament. He promised a return to a promised land. He was wounded three times in battle and gained a reputation for being impossible to kill. He made prophecies that seemed to come true. In early 1870, Te Kooti found safety with Tūhoe tribes. As a result, the Tūhoe suffered many damaging raids where crops and villages were destroyed. This happened after other Māori iwi were tempted by a £5,000 reward for Te Kooti's capture. Te Kooti was finally given safety by the Māori king in 1872. He moved to the King Country, where he continued to develop the rituals and prayers of his Ringatū faith. The government officially pardoned him in February 1883, and he died in 1893.

A 2013 Waitangi Tribunal report said that the actions of Crown forces on the East Coast from 1865 to 1869 (the East Coast Wars and the start of Te Kooti's War) caused more Māori deaths, proportionally, than in any other area during the New Zealand Wars. The report criticized the "illegal imprisonment" of a quarter of the East Coast's adult male population on the Chatham Islands. It also said that the loss of about 43 percent of the male population in the war, many through "lawless brutality," was a stain on New Zealand's history.

Who Fought in the Wars

The New Zealand Wars involved Māori warriors from many different iwi (tribes). Most of these tribes were allied with the Kīngitanga movement. They fought against a mix of Imperial troops, local militia groups, the special Forest Rangers, and kūpapa (Māori who were loyal to the government).

British and Colonial Forces

In 1855, there were only 1,250 British soldiers in New Zealand. Although they were supposed to leave, Governor Browne managed to keep one regiment in New Plymouth. Settlers there were worried about tribal violence spreading. When fighting started in Taranaki in 1860, more soldiers came from Auckland. This brought the total number of regular troops to 450. For many months, the number of Māori fighters was more than the number of troops in Taranaki. In mid-April, three warships and about 400 soldiers arrived from Australia. This marked the start of more and more British troops arriving.

The number of troops grew quickly under Governor Grey. When the second round of fighting began in Taranaki in May 1863, he asked London for three more regiments. He also wrote to Australian governors asking for any British troops they could spare. Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron, the commander of British troops, started the Waikato invasion in July with fewer than 4,000 effective troops in Auckland. But more regiments kept arriving from overseas, quickly increasing his force.

Colonial Defence Force

The Colonial Defence Force was a cavalry (horse-riding) unit of about 100 men. Colonel Marmaduke Nixon formed it in May 1863, and it served in Waikato. Militia forces were also used throughout the New Zealand Wars. The Militia Ordinance 1845 law said that all able-bodied European men aged 18 to 60 had to train or serve within 40 km of their town. The Auckland Militia and Volunteers had about 1,650 active members early in the Waikato campaign. The last force, the Taranaki Militia, finished its service in 1872.

A special 65-man bush-fighting group, the Forest Rangers, was formed in August 1863. These were local farmers who knew the bush well, used guerrilla tactics, and could handle tough conditions. The Forest Rangers split into two companies in November, with the second led by Gustavus von Tempsky. Both companies served in Waikato and Taranaki. Other ranger groups during the wars included the Taranaki Bush Rangers, Patea Rangers, Opotiki Volunteer Rangers, Wanganui Bush Rangers, and Wellington Rangers. From September 1863, the first groups of military settlers also began service in the Waikato. The plan was to have 5,000 of them. They were recruited from the goldfields of Australia and Otago with promises of free land taken from "rebel" Māori. By the end of October, there were over 2,600 military settlers, known as the Waikato Militia, mostly from Australia. By March 1864, troop numbers reached their highest: 9,000 British soldiers, 4,000 Colonial troops (3,600 of them Australians), and a few hundred kūpapa. This made a combined force of about 14,000.

In November 1864, Premier Frederick Weld introduced a policy of "self-reliance" for New Zealand. This meant gradually removing all British troops and replacing them with a colonial force of 1,500. This happened during a growing disagreement between Governor Grey and General Cameron. Grey wanted more military operations to "pacify" the west coast of the North Island. Cameron thought such a campaign was unnecessary and against British policy. Grey stopped Cameron from sending the first regiments away in May 1865. The first regiment finally left in January 1866. By May 1867, only one regiment remained. Their departure was delayed by political pressure, as settlers still felt in "peril." The last British soldiers finally left in February 1870.

Māori Fighters

About 15 of the 26 main North Island tribal groups sent fighters to join the Waikato campaign. Sometimes, these groups were just a single hapū (clan) from a tribe. It was hard for most to stay on battlefields for a long time. This was because they constantly needed to work in their home communities. So, small tribal groups were always coming and going. At Meremere, Paterangi, Hangatiki, and Maungatatauri, between August 1863 and June 1864, Māori kept forces of 1,000 to 2,000 men. But fighters had to leave after each campaign because of work and family needs at home. Belich has estimated that at least 4,000 Māori warriors were involved in total. This was about one-third of all available men.

Even though they didn't have a strict command system, Māori generally followed a consistent plan. They united to build skillfully designed defensive lines, some up to 22 km long. Māori united under skilled military leaders, including Rewi Maniapoto and Tikaokao of Ngāti Maniapoto and Wiremu Tamihana of Ngāti Hauā.

Fighting Styles and Fortifications

Both sides in the New Zealand Wars developed unique ways of fighting. The British aimed to fight a European-style war. This meant directly engaging enemy forces, surrounding, and then capturing fortified positions. The British Army had professional soldiers with experience fighting in different parts of the Empire, including India and Afghanistan. Their officers were trained by men who had fought at Waterloo.

Many Māori fighters had grown up during the Musket Wars. These were decades of fierce intertribal fighting where warriors had perfected building defensive forts around a pā. During the Flagstaff War, Kawiti and Heke seemed to follow a plan of luring colonial forces into attacking a fortified pā. From these strong defensive positions, safe from cannon fire, Māori warriors could fight.

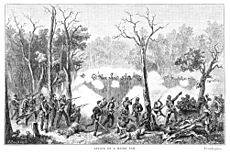

The word pā means a fortified strong point near a Māori village or community. They were built for defense, but also to safely store food. Puketapu Pā and then Ōhaeawai Pā were the first "gunfighter pā." These were built to fight enemies with muskets and cannons. They had strong wooden fences (palisades) in front. These palisades were covered with woven flax leaves (Phormium tenax). The tough flax absorbed much of the force from bullets. The palisade was lifted a few centimeters off the ground. This allowed muskets to be fired from underneath, rather than over the top. Sometimes there were gaps in the palisade that led to traps. There were trenches and rifle pits to protect the people inside. Later, very effective shelters against artillery were added. Pā were usually built so they were almost impossible to surround completely. They often had at least one exposed side to invite attack from that direction. They were cheap and easy to build. For example, the L-Pa at Waitara was built by 80 men overnight. They were also easily given up if needed. The British often launched long expeditions to surround a pā. The pā would withstand their bombing and perhaps one or two attacks, and then Māori would abandon it. Soon after, a new pā would appear in another hard-to-reach place. Many such pā were built, especially during the First Taranaki War, where they formed a ring around New Plymouth, and in the Waikato campaign.

For a long time, the modern pā helped Māori greatly reduce the huge difference in numbers and weapons. At Ōhaeawai Pā in 1845, at Rangiriri in 1863, and again at Gate Pā in 1864, British and colonial forces found that direct attacks on a defended pā were very costly. At Gate Pā, during the 1864 Tauranga Campaign, Māori stayed safe in their underground shelters and trenches during a day-long bombing. When the palisade was destroyed, British troops rushed the pā. Māori then fired at them from hidden trenches, killing 38 and injuring many more. This was the most costly battle for the Pākehā (Europeans) in the New Zealand Wars. The troops retreated, and Māori abandoned the pā.

British troops soon found an easy way to deal with a pā. While cheap and easy to build, a gunfighter pā needed a lot of work and resources. Destroying the Māori food sources and economy around the pā made it hard for the hapū (clan) to support the fighters. This was why Chute and McDonnell led bush-clearing expeditions in the Second Taranaki War.

The biggest challenge for Māori was that their society was not set up for long wars. A long campaign would disrupt food supplies. Also, diseases caused many deaths among Māori. While the British could defeat Māori in battle, these defeats were often not final. For example, taking Ruapekapeka Pā was a British tactical victory. But it was built as a target for the British, and losing it wasn't a big blow. Heke and Kawiti managed to escape with their forces still together. The British army had professional soldiers supported by an economic system that could keep them fighting almost forever. In contrast, the Māori warrior was a part-time fighter who also needed to produce food.

Weapons Used

The main weapon used by British forces in the 1860s was the Pattern 1853 Enfield. This was a rifled musket. It was loaded down the barrel like a regular musket, but the barrel had grooves (rifling). While muskets were accurate up to about 60–80 meters, an 1853 Enfield was accurate to about 300–400 meters in the hands of a skilled soldier. At 100 meters, a skilled soldier could easily hit a person. The rifle was 1.44 meters long, weighed 4 kg, and had a 53 cm bayonet. This rifle was also commonly used by both sides in the American Civil War.

The Calisher and Terry carbine (short rifle) was ordered by the New Zealand Government in 1861. Earlier fighting against Māori showed the need for a shorter rifle suited for fighting in thick bush. This was the favorite weapon of the New Zealand Forest Rangers. They liked it because it was short, light, and could be reloaded while the shooter lay down. The Enfield, however, required the soldier to stand to load the powder. This feature led to a clear victory for the Forest Rangers at Orakau. Several groups of soldiers chased the fleeing Māori, but only the Forest Rangers, with their carbines, could follow them 10 km to the Puniu River, shooting as they went.

Revolvers were mainly used by officers but were given to the Forest Rangers. The most common revolver seemed to be the five-shot Beaumont–Adams .44 percussion revolver. Other revolvers used were the Colt Navy .36 1851 model. The Colt was favored by the Forest Rangers because it was light and accurate. Von Tempsky's second company of the Forest Rangers also used the Bowie knife.

Aftermath of the Wars

Large areas of land were taken from Māori by the government under the New Zealand Settlements Act in 1863. This was supposedly as punishment for rebellion. But in reality, land was taken from both "loyal" and "rebel" tribes. More than 16,000 km2 of land was taken. About half of this was later paid for or given back to Māori control, but often not to the original owners. These land takings had a lasting impact on the social and economic life of the affected tribes.

Right after the wars in Taranaki and the land confiscations, a new town called Parihaka was founded by Te Whiti o Rongomai. It was based on ideas of non-violent resistance. Parihaka's population grew to over 2,000. But the government sent police to arrest Te Whiti and his supporters on 5 November 1881. Another event after the New Zealand Wars was the Dog Tax War of 1898.

The effects of the New Zealand Wars are still felt today. But now, the battles are mostly fought in courtrooms and at negotiation tables. Many reports by the Waitangi Tribunal have criticized the Crown's actions during the wars. They have also found that Māori, too, sometimes broke the Treaty. As part of agreements to settle tribes' historical claims, the Crown has been formally apologizing to tribes since 2011.

Remembering the Wars

The National Day of Commemoration for the New Zealand Wars started in 2017. It is held on 28 October. In 2019, a special plaque was put up for the New Zealand Wars in the New Zealand House of Representatives.

Teaching New Zealand History

The Day of Commemoration came about after a group of students from Otorohanga College in New Zealand. In 2015, they asked parliament to recognize the Wars more. They wanted this part of New Zealand history to be taught in schools. The government agreed. In 2019, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced that teaching history would become compulsory in New Zealand. A draft curriculum was created and tested in 2021. In March 2022, Aotearoa New Zealand Histories and Te Takanga o te Wa (in English and Māori) were officially launched.

Last Veterans

- Edwin Bezar (1838–1936), the last British soldier (and possibly last fighter) from the wars.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de las Tierras de Nueva Zelanda para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de las Tierras de Nueva Zelanda para niños