George Grey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Grey

|

|

|---|---|

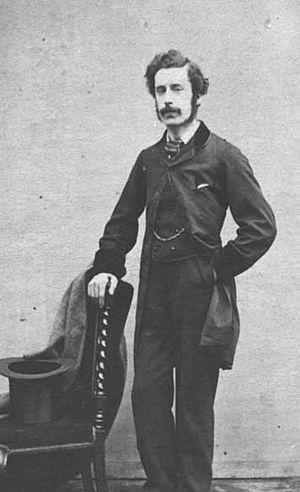

Sir George Grey in 1861

|

|

| 11th Premier of New Zealand | |

| In office 13 October 1877 – 8 October 1879 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governor | George Phipps Hercules Robinson |

| Preceded by | Harry Atkinson |

| Succeeded by | John Hall |

| 3rd Governor of New Zealand | |

| In office 18 November 1845 – 3 January 1854 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | Robert FitzRoy |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Gore Browne |

| In office 4 December 1861 – 5 February 1868 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Premier | William Fox Alfred Domett Frederick Whitaker Frederick Weld Edward Stafford |

| Preceded by | Thomas Gore Browne |

| Succeeded by | Sir George Bowen |

| Governor of Cape Colony | |

| In office 1854–1861 |

|

| Preceded by | George Cathcart (Charles Henry Darling acting) |

| Succeeded by | Philip Edmond Wodehouse (Robert Wynyard acting) |

| 3rd Governor of South Australia | |

| In office 15 May 1841 – 25 October 1845 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Preceded by | George Gawler |

| Succeeded by | Frederick Robe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 April 1812 Lisbon, Portugal |

| Died | 19 September 1898 (aged 86) South Kensington, London, England |

| Spouse |

Eliza Spencer

(m. 1839; died 1898) |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | John Gray (uncle) |

| Education | Royal Grammar School, Guildford |

| Alma mater | Royal Military College, Sandhurst |

| Signature |  |

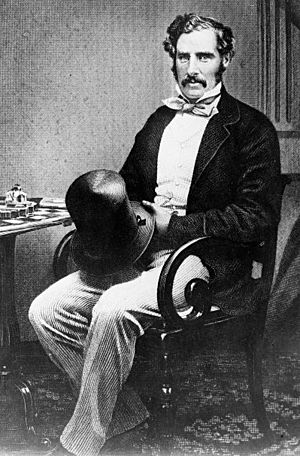

Sir George Grey (born 14 April 1812 – died 19 September 1898) was an important British figure. He was a soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and writer. He held many powerful jobs, including Governor of South Australia, Governor of New Zealand (twice!), Governor of Cape Colony, and even the 11th premier of New Zealand. He played a big part in the colonisation of New Zealand and how Māori land was bought and taken over.

Grey was born in Lisbon, Portugal. This was just a few days after his father was killed in a battle in Spain. He grew up and went to school in England. After serving in the military from 1829 to 1837, he explored Western Australia. In 1841, he became Governor of South Australia. He helped the colony during a tough time. He managed money carefully, making sure the colony was in good shape when he left for New Zealand in 1845.

Grey was the most important person during the European settlement of New Zealand. He was Governor of New Zealand from 1845 to 1853. This was during the early parts of the New Zealand Wars. He learned to speak Te Reo Māori fluently and became an expert in Māori culture. He even wrote about Māori mythology and oral history. He became friends with a powerful Māori leader, Potatau Te Wherowhero, to stop Ngāpuhi from attacking Auckland. He was made a knight in 1848.

In 1854, Grey became Governor of Cape Colony in South Africa. He was praised for helping to end conflicts between local South Africans and European settlers. After some personal difficulties, Grey was made Governor of New Zealand again in 1861. This was three years after Te Wherowhero, who had become the first Māori King, had died. The Kingitanga (Māori King movement) was a big challenge to British rule. Grey found it hard to keep peace with Māori this time. His friendship with Te Wherowhero's successor, Tāwhiao, became very bad. Grey then started an aggressive attack on the Tainui people. He launched the Invasion of the Waikato in 1863. About 14,000 British and colonial soldiers attacked 4,000 Māori and their families.

Grey became Premier of New Zealand in 1877 and served until 1879. He remained a symbol of British control. Some people saw Grey as a "great British leader." However, he could also be difficult and demanding. He is still a debated figure in New Zealand because of the wars he started against Māori to take their land.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Grey was born in Lisbon, Portugal. He was the only son of Lieutenant-Colonel George Grey, who died in battle just days before Grey was born. His mother, Elizabeth Anne Vignoles, heard about her husband's death, which caused Grey to be born early.

Grey went to the Royal Grammar School, Guildford in England. He then joined the Royal Military College, Sandhurst in 1826. In 1830, he became an ensign in the 83rd Regiment. While his regiment was in Ireland, he felt great sympathy for the poor Irish people. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1833.

Exploring Australia

In 1837, when he was 25, Grey led an expedition to explore North-West Australia. At that time, British settlers didn't know much about the area. Grey and his team hoped to find a large river that might make the land good for settlement. They landed at Hanover Bay in December. They faced many challenges, including boat wrecks, getting lost, and Grey being injured by a spear during a fight with Aboriginal people. The expedition failed, and they were rescued by a ship.

In 1839, Grey went on a second exploration trip to the north. Again, his party was shipwrecked at Kalbarri. They were the first Europeans to see the Murchison River. They then had to walk to Perth. They survived thanks to a Whadjuk Noongar man named Kaiber, who found food and water for them. Around this time, Grey learned the Noongar language.

Because of his interest in Aboriginal culture, Grey was promoted to captain in July 1839. He became a temporary Resident Magistrate at King George Sound, Western Australia.

Family Life

On 2 November 1839, Grey married Eliza Lucy Spencer. Their only child, born in 1841, died when he was five months old. Their marriage was not a happy one. Grey and his wife separated in 1860. They formally reunited in 1897, shortly before they both died.

In 1861, Grey adopted Annie Maria Matthews after her father, his half-brother, passed away.

Governor of South Australia

Grey was the third Governor of South Australia from May 1841 to October 1845. The British government was impressed by Grey's ideas on how to govern indigenous people. This led to his appointment as governor.

Grey took over from George Gawler, who had spent a lot of money on public buildings, causing the colony to go bankrupt. Grey quickly cut spending. The colony soon had full employment, and exports of goods increased. The discovery of copper at Burra Burra in 1845 also greatly helped the colony's finances.

Aboriginal Witnesses Act

In 1844, Grey introduced a law called the Aboriginal Witnesses Act. This law said that unsworn statements from Aboriginal Australians could not be used in court. This had a big impact later on, as it often meant that evidence from Aboriginal people about massacres against them by European settlers was not accepted in court.

Governor of New Zealand

Grey was Governor of New Zealand two times: from 1845 to 1853, and from 1861 to 1868.

During this time, more and more Europeans settled in New Zealand. By 1859, the number of Pākehā (Europeans) was about the same as the number of Māori, around 60,000 each. Settlers wanted land, and some Māori were willing to sell. However, there was also strong pressure from the Māori King Movement to keep Māori land. Grey had to balance the settlers' demand for land with the promises made in the Treaty of Waitangi. The treaty said that Māori chiefs would keep "exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands." It also said that Māori would only sell land to the British Crown.

First Term as Governor

Grey became the third Governor of New Zealand in 1845. Before he arrived, there had been violence over land in the Wairau Valley in 1843. This was known as the Wairau Affray. In 1846, Grey arrested the Māori war leader Te Rauparaha on a different charge. This arrest was controversial among the Ngāti Toa people.

Hōne Heke and the Flagstaff War

In March 1845, Māori chief Hōne Heke started the Flagstaff War. This war happened because the Ngāpuhi people felt that the British were not keeping the promises of the Treaty of Waitangi (1840). On 18 November 1845, George Grey arrived as governor. Hōne Heke showed his anger by cutting down the flagstaff at Kororareka. This flagstaff used to fly the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand, but now it flew the Union Jack (British flag).

Heke had several complaints about the Treaty of Waitangi. The rebellion was against the colonial forces. Many Ngāpuhi people, led by Tāmati Wāka Nene, sided with the government. The British forces were small and had been defeated in one battle. But Grey had more money and troops, including powerful cannons. He ordered an attack on Kawiti's fort at Ruapekapeka on 31 December 1845. This forced Kawiti to retreat. Heke realized the British had many more resources than he did.

After the Battle of Ruapekapeka, Heke and Kawiti wanted peace. They asked Tāmati Wāka Nene to help them talk with Governor Grey. Grey accepted Nene's advice that Heke and Kawiti should not be punished. The fighting in the north ended, and no Ngāpuhi land was taken.

Land Disputes and Conflicts

European settlers arrived in Wellington in 1839. The New Zealand Company claimed to buy huge amounts of land. Disputes over who owned the land continued when Grey became governor.

Unresolved land disputes led to fighting in the Hutt Valley in 1846. The Ngati Rangatahi people wanted to keep their land. Their leader was Te Rangihaeata. Governor Grey sent troops into the area. By February, he had nearly a thousand men, including some Māori allies.

Māori attacked Taita on 3 March 1846 but were pushed back. Grey declared martial law in the Wellington area. Fighting continued, including a big attack on Boulcott's Farm on 6 May. On 6 August 1846, the Battle of Battle Hill was fought, after which Te Rangihaeata left the area.

Grey learned that Te Rauparaha was secretly helping the Māori who were attacking settlers. In a surprise attack on his pā (fortified village) at Taupo (now Plimmerton) on 23 July, Te Rauparaha was captured. He was held prisoner until January 1848. His son, Tāmihana, stopped a planned uprising by his people. Tāmihana sold the Wairau land to the government. Grey spoke to Te Rauparaha and convinced him to give up all claims to land in the Wairau valley. Te Rauparaha was then allowed to return to his people.

Government in Auckland

Auckland became the new capital in March 1841. By the time Grey became governor in 1845, it was a busy commercial center. After the war in the north, the government wanted to create a buffer zone of European settlement between the Ngāpuhi and Auckland. Later, fears that Waikato Māori might attack Auckland also played a part in the Invasion of Waikato in 1863.

Grey had to deal with newspapers that strongly supported the settlers' interests. Some newspapers attacked Governor Grey, while others supported ordinary settlers and Māori. During the northern war, some newspapers and official communications blamed missionaries for the Flagstaff War. However, Grey later changed his mind about the missionaries' role.

Grey was very clever and sometimes manipulative. His main goal was to make sure British rule was strong in New Zealand. He used force when he felt it was needed. But his first way to get land was to weaken the close ties between missionaries and Māori chiefs.

Self-Government and Laws

In 1846, the British Parliament passed the New Zealand Constitution Act 1846. This law gave the colony some self-government. However, Māori had to pass an English test to take part in the new government. Grey told the British government that this law would cause more fighting. He felt the settlers were not ready for self-government.

The British government agreed and suspended most of the 1846 Act. Grey then wrote a draft for a new Constitution Act in 1851. This draft suggested having both local and central elected assemblies. It also allowed for special Māori districts. The British Parliament adopted Grey's constitution, which became the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852.

After the first parliament was elected in 1853, the colony gained more control over its own government in 1856. However, the governor kept control over "native affairs," meaning Māori affairs and land. This caused arguments between the Governor and the elected parliament.

The Treaty of Waitangi was meant to stop Māori land from being sold to anyone other than the Crown. This was to protect Māori from unfair land deals. At first, this system worked well. Māori were keen to sell land, and settlers were keen to buy.

Grey's Legacy from His First Term

Grey tried to assure Māori that he was following the Treaty of Waitangi and would respect their land rights. In the Taranaki district, Māori were unwilling to sell their land. But elsewhere, Grey was more successful. About 33 million acres (130,000 km2) were bought from Māori. This allowed British settlements to grow quickly. Grey was less successful in his efforts to make Māori adopt British ways. He didn't have enough money for his plans.

During his first time as Governor of New Zealand, Grey was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1848. He chose Tāmati Wāka Nene as one of his special attendants for the ceremony.

Grey gave land for the Auckland Grammar School in 1850. The school was officially recognized in 1868. Some historians believe Grey's administration was "ramshackle" and involved "broken promises" to Māori. Grey's collection of Māori artifacts, one of the earliest from New Zealand, was given to the British Museum in 1854.

Second Term as Governor

Grey was appointed Governor again in 1861 and served until 1868. His second term was very different because he had to deal with an elected parliament, which had been set up in 1852.

Invasion of the Waikato

Before Grey's return, there were growing tensions in Taranaki over land ownership. This led to the First Taranaki War from 1860 to 1862.

The leaders of the King movement (Kīngitanga) told Governor Browne that the Waikato tribes had never signed the Treaty of Waitangi. They said they were a separate nation. Browne saw this as disloyalty and planned to invade Waikato.

Grey launched the Invasion of the Waikato in June 1863. This happened because of growing tension between the Kingites and the government. Grey worried about a violent attack on Auckland by Kingite Māori. He gave an ultimatum on 9 July 1863: all Māori living between Auckland and the Waikato River had to promise loyalty to Queen Victoria or be moved south of the river.

The war brought thousands of British troops to New Zealand. At its peak in March 1864, there were about 14,000 troops. The invasion included the Battle of Rangiriri in November 1863, which had more casualties than any other battle in the New Zealand Wars. It also included the attack on Rangiaowhia in February 1864, a village mostly with women, children, and older men. The 100 Māori deaths there are seen by some as murder, not an act of war.

The campaign ended with the Kingitanga Māori retreating into the North Island's rugged interior. The colonial government then confiscated about 12,000 km2 of Māori land. This defeat and land loss caused poverty and bitterness for the King Movement tribes. In 1995, the government admitted that the 1863 invasion and land confiscation were wrong and apologized.

In the late 1860s, the British government decided to remove its troops from New Zealand. At this time, Māori chiefs Te Kooti and Titokowaru were having military successes, alarming the government and settlers. Grey tried to stop the troops from leaving. In the end, the British government removed Grey from his position as Governor in February 1868. He was replaced by Sir George Bowen.

Legacy of Grey's Second Term

Some Māori greatly respected Grey. He often traveled with Māori chiefs. He encouraged leading chiefs to write down their Māori traditions, legends, and customs. His main teacher, Wiremu Maihi Te Rangikāheke, taught Grey to speak Te Reo Māori.

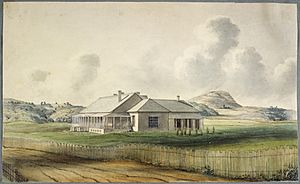

Grey bought Kawau Island in 1862. He spent a lot of his own money developing the island for 25 years. He made Mansion House bigger and planted many native and non-native trees. He also brought in many exotic birds and animals, like possums and wallabies. These animals later became harmful invasive species. He also collected many rare books, manuscripts, artworks, and Māori artifacts.

In 1865, during Grey's second term, the capital of New Zealand was moved to Wellington. This was seen as a better choice because it was closer to the South Island.

Governor of Cape Colony

Grey was Governor of Cape Colony from 1854 to 1861. He helped start Grey College, Bloemfontein in 1855 and Grey High School in Port Elizabeth in 1856. In 1859, he laid the foundation stone for the New Somerset Hospital, Cape Town. When he left in 1861, he gave the National Library of South Africa a wonderful collection of old manuscripts and rare books.

As governor, Grey faced a growing rivalry between the eastern and western parts of the Cape Colony. There was also a small but growing movement for local democracy and more independence from British rule. Grey handled the local people firmly. He tried to protect them from white settlement while also using reservations to make them less military. He often helped settle disputes between the government and local people. He believed that a federated South Africa would be good for everyone.

Grey was recalled (removed from his post) in 1859. However, a change in the British government led to him being offered another term. He was told to stop pushing for a federation of South Africa and to follow instructions. Grey believed the South African colonies should be larger, but the British government didn't support him. He was still working on this when war broke out with the Māori. It was then decided that Grey should become governor of New Zealand again.

Later Political Career in New Zealand

After his time as governor, Sir George Grey returned to New Zealand and became involved in politics. In 1875, he was elected Superintendent of Auckland Province. He also became a Member of Parliament for Auckland West and Thames.

Grey was against getting rid of the provinces, but he couldn't stop it. The provincial system was ended in 1876. On 13 October 1877, he became Premier of New Zealand. His time as premier was difficult, and he often argued with the governor. Historians generally see his time as premier as unsuccessful. He resigned as prime minister in October 1879.

Grey continued to be elected to Parliament for different areas, including Thames, Auckland East, and Auckland Central. In 1889, Grey suggested a new law that would allow a "British subject" to be elected as Governor.

By 1890, Grey was not well. He retired from politics and went to Australia to recover. While there, he took part in the Australian Federal Convention. When he returned to New Zealand, people asked him to run for a seat in Auckland again. He agreed, but only if he didn't have to fight a contested election. He was elected without opposition in 1891 and again in 1893. He left for England in 1894 and resigned his seat in 1895.

Death

Grey died in London on 19 September 1898, at the age of 86. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral.

Places and Institutions Named After Grey

Many places are named after Sir George Grey. In New Zealand, these include Greytown, the Grey River (and so the town of Greymouth), and the Auckland suburb of Grey Lynn. In Australia, there is the Division of Grey, an electoral area in South Australia, and the town of Grey in Western Australia. Grey Street, Melbourne and Grey Street, Onehunga are also thought to be named after him. Grey's Bay in Geraldton, Western Australia, is also named after him.

In South Africa, Grey helped found the Grey Institute (now Grey High School) in Port Elizabeth, Grey College, Bloemfontein, and Grey's Hospital in Pietermaritzburg. Grey's Pass near Citrusdal and the towns of Greytown, KwaZulu-Natal and Greyton, Western Cape are named for him. Lady Grey, Eastern Cape is named after his wife. The main street in Paarl (Western Cape) is named Lady Grey Street after his wife. Cape Town has Sir George Grey Street.

Grey's Spring, also called Grey's Well, is a historic site in Kalbarri, Western Australia.

The Rhodesian Grey Scouts was also named after George Grey.

Animals and Plants Named After Grey

Several living things are named after Grey. These include Menetia greyii, a type of lizard, and two other mammals and a bird.

The plant genus Greyia (wild bottlebrush), which grows only in southern Africa, was also named after him.

Popular Culture

The Governor, a TV show based on Grey's life, was made in New Zealand in 1977. It starred Corin Redgrave as Grey. The show was praised but also caused some debate because of its large budget at the time.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: George Grey para niños

In Spanish: George Grey para niños