Māori culture facts for kids

Māori culture (called Māoritanga in Māori) includes the customs, practices, and beliefs of the Māori people. They are the original people of New Zealand. This culture comes from the wider Eastern Polynesian culture. It is also a special part of New Zealand's culture. Because many Māori live around the world, and Māori designs are popular, you can find parts of their culture everywhere. The word Māoritanga means "a Māori way of life."

Māori culture has changed over four main periods. First, when it was similar to other Polynesian cultures (Archaic period). Second, before many Europeans arrived (Classical period). Third, the 1800s, when Māori met European visitors and settlers. Finally, the modern era since the 1900s. Today, Māoritanga is shaped by more people living in cities. It is also shaped by closer contact with New Zealanders of European descent (called Pākehā). There has also been a strong effort to bring back traditional practices.

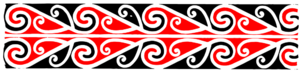

Traditional Māori arts are a big part of New Zealand art. These include whakairo (carving), raranga (weaving), kapa haka (group performance), whaikōrero (public speaking), and tā moko (tattoo). The patterns and figures in these arts tell stories about Māori beliefs and family histories (Whakapapa). Artists often use old techniques. But today, Māoritanga also includes modern arts like film, TV, poetry, and theatre. The Māori language is called te reo Māori. Sometimes it is just called te reo (meaning "the language"). In the early 1900s, it seemed like te reo Māori and other parts of Māori life might disappear. But in the 1980s, schools like Kura Kaupapa Māori started teaching te reo. This helped both Māori and European students learn the language.

Contents

How Māori Culture Changed Over Time

Māori culture is closely linked to the culture of Polynesia. New Zealand is at the southwest corner of the Polynesian Triangle. This is a part of the Pacific Ocean with three main island groups. These are the Hawaiian Islands, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and New Zealand (called Aotearoa in Māori). The many island cultures in this triangle share similar languages. These languages came from a very old language used in Southeast Asia 5,000 years ago. Polynesians also share traditions like religion, social groups, myths, and tools.

Experts believe all Polynesians came from a group of people who moved from Southeast Asia. Other main Polynesian cultures include Rapa Nui, Hawaii, Marquesas, Samoa, Tahiti, Tonga, and Cook Islands. Over thousands of years, people made amazing long sea journeys. They used their navigation skills to reach distant places like Hawaii, Rapa Nui, and Aotearoa.

Polynesian sailors were skilled navigators and astronomers. They traveled long distances by sea. The fact that many women were among the first settlers in New Zealand suggests these trips were planned, not accidental. The best evidence shows that New Zealand was first settled around 1280 CE. The settlers came from the Society Islands. In 1769, a skilled Society Island navigator named Tupaia joined Captain Cook on his ship, the Endeavour. Even after hundreds of years, Tupaia could understand the Māori language. It was very similar to his own language. His ability to translate helped avoid many problems between European explorers and Māori in New Zealand.

The Archaic Period (around 1300 AD)

The time from about 1280 to 1450 is often called the Archaic period. It's also known as the "Moa-hunter period." This is because the moa, a large flightless bird, was a big part of the early settlers' diet. During this time, Māori got used to their new home. But their culture changed little from the tropical Pacific peoples they came from. Many edible plants were brought from their home islands. Of these, kūmara (sweet potato) became the most important. In the far South, it was too cold to grow these crops. Large amounts of tī tubers were eaten. These were slow-cooked in big umu or hāngi (earth ovens). This removed poison and made them slightly sweet. Shellfish, fish, sharks, and seals were also common foods. Native dogs (kurī) and rats came from the Pacific Islands. The rats had a huge impact on New Zealand wildlife. Dogs were used for hunting and also as food.

The new environment brought challenges. The cold climate meant tropical crops needed careful care to grow. Some did not grow at all. Kūmara was a key crop. Much of the work to grow kūmara became part of rituals. It was even linked to Rongomātāne (Rongo), a high-ranking god (atua). Kūmara appeared in some proverbs (whakataukī). For example, "Kaore te kūmara e kōrero mo tōna māngaro" (the kūmara does not speak of its own sweetness) taught people to be humble.

Seasonal activities included gardening, fishing, and bird hunting. Some tasks were for men, others for women. But many group activities involved gathering and growing food.

These early settlers explored New Zealand to find good stones for tools. Main stone areas included Mayor Island, Taupo, and Kerikeri for obsidian (volcanic glass). They soon found pounamu (greenstone or jade) and argillite (pakohe) in the South Island. Stone was used for everything: chopping wood, cutting food, as anchors for waka (canoes) and fishing nets. It also kept heat in a hangi (earth oven). These practices were typical of East Polynesian culture at the time.

Two Polynesian items connect early settlers to Polynesia. One is a shell from the South Pacific islands, made into a small chisel. It was found at Wairau Bar and is about 1300 years old. The other is a 6 cm long pearl fishing lure found at Tairua in 1962. This lure is from the early to mid-14th century. It was found at a small moa-hunter camp. Finding Mayor Island obsidian on the Kermadec Islands (halfway to Polynesia) suggests people made return journeys.

The new land also offered new chances. Māori learned to use local things like pounamu, native timber, harakeke (flax), and many birds. They made tools, food, beautiful ornaments, and clothes. This adapting to the new environment led to the Classical Māori culture.

The Classical Period (around 1500 AD)

Around the 15th century, Māori items started to change. They moved from an East Polynesian style to a "classical" Māori style. This style lasted into the 18th and 19th centuries. At the same time, Māori groups became less nomadic. They settled in specific areas and relied more on gardening for food. Stored food like kūmara needed protection from other groups. So, large forts called pā were built on hills. This shows a more warlike, tribal culture developed. Not all parts of this culture were adopted everywhere, especially in the South Island where kūmara was harder to grow.

Cultural Changes from European Contact (around 1800 AD)

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, very few Europeans visited New Zealand. So, Māori culture's main values changed little. Henry Williams thought there were only 1100 Europeans in the North Island in 1839. About 200 were missionaries. The total European population in the Bay of Islands was about 500-600. The northern Māori population at that time was about 30,000 to 40,000. This was down from about 100,000 fifty years before. This drop was mostly due to diseases and the Musket Wars.

For decades, European missionaries, mostly in the North Island, had little effect on Māori behavior. Missionaries were often shocked by the violence they saw.

In the South Island, the Māori population was very small. Whalers set up stations along the coast. They formed communities where Māori and Europeans worked together. In the early 1800s, chiefs often gave whalers Māori wives, sometimes their daughters. By the 1820s, European men had married about 200 Māori women in the coastal area. This was about half of all marriageable women in the South Island. Māori men found it hard to find wives.

Contact with Europeans gave Māori access to goods from England. By 1800, the desire for iron objects like ship nails was strong. This led to Māori trading behavior. Māori were generally very curious about European culture. They showed a great ability to accept changes and fit them into their lives. Marion Du Fresne gave northern Māori potatoes, wheat, onions, goats, pigs, chickens, and other food to raise. Potatoes and pigs quickly became a key part of Māori farming in the north. But these new foods were mostly for trading. Māori still ate fish and fern roots, plus kūmara. Later, as Māori grew large potato fields, whalers would visit to trade for fresh supplies.

One big change was how quickly trade happened. In traditional Māori custom (tikanga), if you gave something, you didn't expect an immediate return. Gifts were mainly food, which depended on the season. When dealing with Europeans, Māori learned that immediate payment was expected. Gift-giving was different in Māori culture. Gifts were given to show respect for mana (power or authority).

Burial practices also changed to include Christian ideas. Bodies were usually buried by the mid-1840s. Sometimes, coffins decorated with Māori designs were used. These were hung in trees or on poles. These were considered very tapu (sacred).

Cultural Concepts

Some basic ideas of Māoritanga are found throughout Polynesia. But they have all been shaped by New Zealand's unique history and environment.

Mana (Power and Prestige)

Mana is a Māori cultural idea meaning sacred power or authority. It is a special gift from the gods to chiefs and experts (tohunga). A chief can either lose or increase their mana. Historian Judith Binney says that keeping and growing the mana of family groups (whanau and hapū) is central to Māori culture. She explains that Māori history can be confusing because it uses myths that go back a long time. Also, the exact time doesn't matter as much in Māori stories. A person today might tell a story about their family from centuries ago, but they appear as if they were there.

A key part of leadership is linking the storyteller to a famous historical figure with mana. This is why knowing your family history (whakapapa) is so important. In Māori culture, names of people and places can change. People might have several names depending on the situation. In the past, family groups (hapū) changed names if they moved to a new area where a different name was better. One reason for changing names was to get access to resources. As a hapū moved with the seasons to use different resources, its name changed to reflect an ancestor who had rights to that resource. Being connected to a powerful hapū with many famous ancestors was important for safety and survival. Since Māori communication was mostly spoken, stories changed to fit the needs of each family group.

Whakapapa (Genealogy)

Whakapapa is the history and family line of a person, object, or place. A person's whakapapa shows their mana and tribal connections. It can be recited as an introduction (mihimihi).

Utu (Balance and Harmony)

Utu is often thought of as 'revenge'. But more broadly, "utu" means keeping balance and harmony in a community. In "utu," a mistake must always be fixed, and a kindness must be repaid. How this is done can vary a lot. When gifts are exchanged, "utu" creates and keeps social connections. "Utu" brings back balance if social relationships are broken. A type of "utu," called "muru," means taking a person's belongings as payment for a wrong deed against a person, group, or society.

Gift exchange followed three main rules. First, giving had to seem free and unplanned, with no demand for a return gift. Second, the receiver had to give back something of equal or greater value. Third, the system meant that new social ties were made to keep the exchanges going. Not responding meant losing mana or influence. If people traveled far to give a gift, an immediate return gift was expected. But often, because food supplies depended on seasons, it was accepted that a return gift would be given later. While a gift created an obligation to return the favor, so did an insult. The response might be a fight. Historian Angela Ballara says that fighting was a "learned, culturally determined [response] to offenses against the rules of Māori society."

Kaitiaki (Guardianship)

Kaitiaki (or kaitiakitanga) means guardianship or protection. Today, it mostly refers to protecting the natural environment.

Tapu (Forbidden and Sacred)

Tapu is similar to mana. Together, they help keep things in harmony. Tapu supports order in society. It can be seen as a legal or religious idea. It focuses on being "forbidden" and "sacred." When something is "tapu," it is often seen as very valuable and important. It is set aside by the gods.

Kaumātua (Tribal Elders)

Kaumātua (or sometimes Kuia for women) are respected tribal elders in a Māori community. They are chosen by their people. People believe these elders can teach and guide current and future generations. It is against the rules of mana for anyone to say they are an elder. Instead, the community recognizes an elder's kaumātua status. In the past, kaumātua were thought to be "the reincarnation of a person who had gained a special status after death, and who had become the protector of the family."

Koha (Gifts)

Koha are gifts given to hosts. They are often food or traditional items. Today, money is most common. Traditionally, koha is given freely and from the heart. So, saying how much to give goes against its spirit. More and more, the koha is a set amount per person. This is told to guests privately to avoid embarrassment. Those receiving the koha trust the givers' aroha (empathy), manaakitanga (caring), and wairua (spirit) to make sure it is enough. Thanks for koha are always very warm.

Matariki (New Year)

Matariki, the "Māori New Year," celebrates the first rising of the Pleiades star cluster. This happens in late May or early June. Traditionally, the exact time for Matariki celebrations varied. Some groups celebrated right away. Others waited until the next full moon. It is a day to remember those who have passed away. It is also a day to celebrate new beginnings. People celebrate with prayers, feasting, singing, and music. After not being widely celebrated for many years, Matariki is now becoming more popular. It is celebrated in different ways over a week or month, from early June to late July.

Art and Entertainment

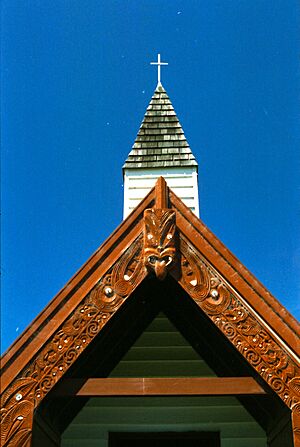

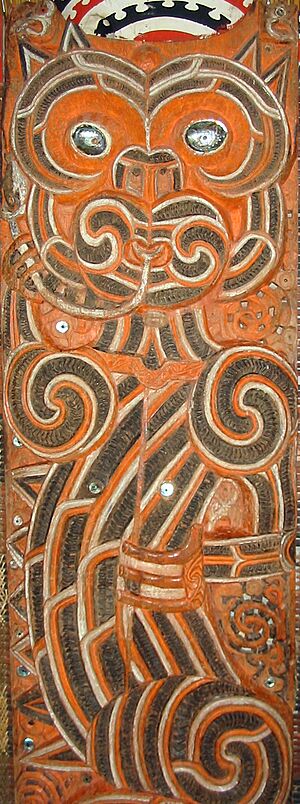

Carving (Whakairo)

Before Europeans arrived, Māori stories and legends were passed down by speaking. They were also shown through weaving and carving. Some surviving Te Toi Whakairo, or carving, is over 500 years old. Tohunga Whakairo are the master carvers. Māori believed that the gods created and spoke through these master craftsmen. Carving was a tapu (sacred) art. It followed strict rules. Wood pieces that fell off during carving were never thrown away. They were also not used for cooking. Women were not allowed near Te Toi Whakairo.

Weaving (Raranga) and Traditional Clothing

From early sealing days, Māori working in sealing camps in the South Island started wearing European clothes. Traditional clothing made from flax and dog skins was not commonly used by 1850. This type of clothing took a long time to make. It also did not offer much protection or warmth. European clothing became widely available from traveling sellers. These sellers also sold pipes, tobacco, axes, and other household items. Blankets were very common. They were worn as kilts, cloaks, or shawls. Blankets were used at night to help keep warm. From the late 1800s until today, traditional clothing is only used for special ceremonies.

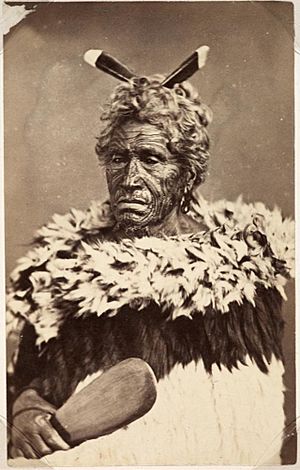

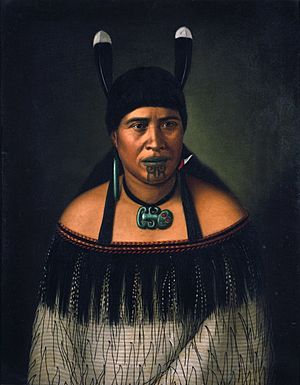

Tattooing (Tā Moko) and Painting

Face carving or tattooing was a traditional practice. It was especially done by men of high rank, but also by women. The facial tattoo showed details about the wearer's family line, status, origin, and achievements. Before Europeans arrived, tattooing was a sacred activity with many rituals.

Music (Te Pūoro) and Dance (Kapa Haka)

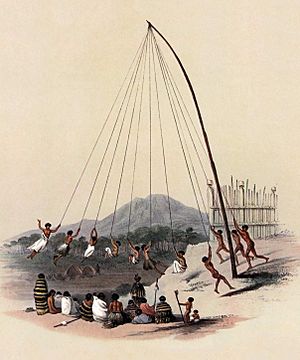

Kapa haka (haka groups) often meet to practice and perform cultural items. These include waiata (songs), especially action songs, and haka for entertainment. Poi dances may also be part of their performance. Traditional instruments sometimes play with the group. But the guitar is also commonly used. Many New Zealand schools now have a kapa haka group as part of their Māori studies. Today, national kapa haka competitions are held. Groups are judged to find the best performers. These events draw large crowds.

The haka is an action chant. It is often called a "war dance." But it is more of a chant with hand gestures and foot stomping. Warriors originally performed it before a battle. They showed their strength by challenging the other side. Now, New Zealand rugby and rugby league teams often perform the haka before a game. There are many different haka. One, "Ka mate" by Te Rauparaha, is much more famous than any other.

Sport

Māori fully participate in New Zealand's sports culture. Both the national Rugby league and Rugby Union teams have had many Māori players. Other sports also feature many Māori players. There are also national Māori rugby union, rugby league, and cricket teams. These teams play in international competitions, separate from the main national ones.

Ki-o-rahi and tapawai are two sports of Māori origin. Ki-o-rahi got a big boost when McDonald's chose it to represent New Zealand.

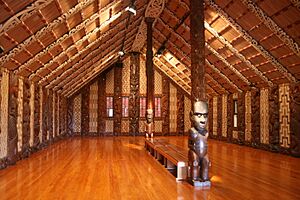

Marae (Community Meeting Place)

The best place for any Māori cultural event is a marae. This is a special area of land where a meeting house or wharenui (meaning "big house") stands. A marae is the center for much of Māori community life. The Māori language is generally used in ceremonies and speeches. But translations are given when the main people are not Māori speakers. More and more, New Zealand schools and universities have their own marae. This helps teach Māori language and culture.

The marae is a community center for ceremonies. Meetings and ceremonies happen there following traditional rules. The marae shows group unity. It usually has an open area in front of a large carved meeting house. There is also a dining hall and other buildings for visitors. Official events happen on the marae. These include formal welcomes, celebrations, weddings, christenings, reunions, and tangihanga (funerals). Older people have authority on the marae. They pass down traditions and cultural practices to younger people. This is mainly done through oral tradition. These traditions include genealogy, spirituality, public speaking, and politics. They also include arts like music, performance, weaving, or carving.

A hui or meeting usually takes place on a marae. It starts with a pōwhiri (a welcoming ceremony). If a visitor is important, they might be welcomed with a challenge by a warrior. The warrior uses a taiaha (traditional fighting staff). Then, they offer a sign of peace, like a fern frond. Accepting the sign shows the visitor's courage and mana (authority, prestige). The pōwhiri has a strict structure. Speeches from both hosts and guests follow a traditional pattern. Their order is set by the kawa (protocol) of that place. Songs (waiata) follow the speeches. Hui are held for business, parties, or life events like baptisms, marriages, and deaths. It is nice if foreign guests can say a few words in Māori and sing a familiar song together.

Marae Protocols

The details of the rules, called "tikanga" or "kawa", differ by iwi (tribe). But in all cases, locals and visitors must follow certain rules. This is especially true during welcoming ceremonies. When a group of people comes to stay on a marae, they are called manuhiri (guests). The hosts of the marae are known as tangata whenua. If other groups of manuhiri arrive, the first group of manuhiri becomes tangata whenua for welcoming the new group.

Marae Food

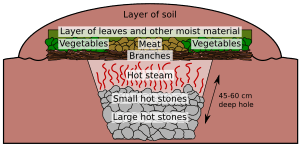

Marae have modern cooking facilities. But the traditional hāngi is still used for large groups. This is because the food it makes is very tasty. A hāngi involves digging a shallow hole in the ground. A fire is made in the hole, and stones are placed on top. When the stones are hot, food is placed on them. Meat goes first, then vegetables like kūmara, potatoes, and pumpkin. The hāngi is then covered with leaves, flax mats, or wet sacks. Soil is piled over it to seal in the heat and cook the food.

Marae Events

Just like in old times, marae are still used for many ceremonies. These include birthdays, weddings, and anniversaries. The most important events on marae are tangihanga. Tangihanga are how the dead are farewelled. They also support the family members left behind in Māori society. The importance of tangihanga on the marae means they take priority over any other gathering.

The "tangi" is a Māori funeral. It almost always happens at the deceased person's home marae. The rituals followed are mostly Christian. The tangi begins with a pōwhiri to welcome guests. It is normal for Māori to travel very long distances to attend a loved one's tangi. Black clothes are often worn, following old European customs. Guests will speak formally about the deceased on the Marae atea. They often refer to tribal history and use humor. Sadness is often shown to create comfort and unity. Speeches are supported by Waiata (songs). The deceased's family sits by the coffin on the wharenui porch. They do not speak or reply. The family may hold or display photos of the deceased or important ancestors. A tangi can last for several days, especially for a person of great mana. Rain during a tangi is seen as a sign of sorrow from the gods.

Marae Oral Tradition

The history of each tribal group is kept through stories, songs, and chants. This shows how important music, stories, and poetry are. Public speaking is especially important in welcoming ceremonies. It is important for a speaker to include hints to traditional stories and a complex system of proverbs, called whakataukī. Oral traditions include songs, calls, chants, haka, and special speech patterns that remember the people's history.

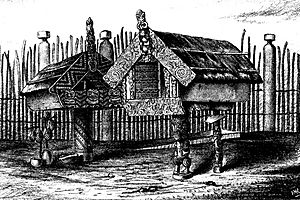

Other Traditional Buildings

The usual building in an old Māori settlement was a simple sleeping whare puni (house/hut). It was about 2 by 3 meters. It had a low roof, an earth floor, no window, and one low doorway. A small open fire provided heat in winter. There was no chimney.

Materials used for building changed by area. But raupo reeds, flax, and totara bark shingles for the roof were common. Similar small whare, but with drains inside, were used to store kūmara on sloped racks.

In the classical period, more whare were inside pa (forts) than after Europeans arrived. A chief's whare was similar but larger. It often had full headroom in the middle, a small window, and a partly covered front porch. During conflicts, the chief lived in a whare on the tihi (summit) of a hill pa. In colder areas, like the North Island central plateau, whare were often partly dug into the ground for better warmth.

Food was not cooked in the sleeping whare. It was cooked outside or under a kauta (lean-to). Young trees with branches removed were used to store and dry items like fishing nets or cloaks. Valuable items were kept in raised storage shelters called pataka. Other structures included large racks for drying fish.

During the building of important structures, slaves were sometimes sacrificed. This was done to show the building's importance and to get protection from the gods. For smaller buildings, small animals were sacrificed to make them special.

Traditional Māori whare continued to be used in rural areas even after Europeans arrived. They were usually very small with dirt floors and many pests, especially fleas. In winter, a central fire filled the whare with smoke. This smoke slowly went out through the roof. Even in 1849, George Cooper described a village as "a wretched place, containing about a dozen miserable raupo huts all tumbling to pieces." In the 19th century, settlements were based on family groups (hapū). Five buildings became standard: the sleeping whare, Kauta (communal cookhouse/shelter), whata (wood store), pataka (storehouse), and from the 1870s, the wharepuni (community meeting house). A lot of money and mana was put into making meeting houses more detailed. They became a source of pride for the hapū or iwi.

A meeting house likely had carvings outside. As European tools were used, they had intricate carvings and woven panels inside. These showed tribal history. Rotorua became a center for excellent carving. This was encouraged by Māori Members of Parliament (MPs) in the Young Māori party. Skilled carvers traveled widely, using their talents in many places. Meeting houses became places for tribal celebrations or political meetings, especially after the Land Wars in the 1860s. They were a place to show generosity and increase mana with big feasts and entertainment. By the 1900s, Wharepuni were common. They averaged 18–24 meters long by 8 meters wide. There were no Māori buildings this size before Europeans arrived. As Māori learned about European building styles, they added features like chimneys, fireplaces, bigger doorways, and windows. They also used sawn timber.

Mythology and Religion

Traditional Māori religion has changed little from its tropical Eastern Polynesian roots. So, all things were thought to have a life force or mauri. The god Tangaroa was the spirit of the ocean and the ancestor of all fish. Tāne was the spirit of the forest and the origin of all birds. Rongo was the spirit of peaceful activities and farming. He was the ancestor of cultivated plants.

Today, Christianity plays an important role in Māori religion. In the early 1800s, many Māori accepted Christianity. Many joined the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church. Both are still very important in Māori society.

Missionaries

Christian missionaries insisted Māori stop cannibalism before they could be baptized. They also tried to stop polygamy (having multiple wives). Some early missionaries felt bad for abandoned wives. But Henry Williams said that polygamy meant Māori could not be baptized. Missionaries also banned traditional funeral rites. Catholic missionaries arrived 20 years after the Church of England missionaries. They were less worried about stopping these customs before Christian conversion. They thought they could influence Māori better after baptism. They were successful in getting many converts in the western Hokianga district.

Missionaries did not arrive in the Waikato until about 1834-35. Mission stations were set up in several places. Missionaries helped explain the Treaty of Waitangi to the Tainui people in 1840.

Early Māori Interpretation of Christianity

In the 1830s, Te Atua Wera started the Papahurihia Faith. It was against the missionaries. It mixed Christian, Jewish, and Māori customs. They held services on Saturday and called themselves Hurai or Jews. Te Atua Wera went back to being more of a traditional tohunga (expert) by the late 1830s. Te Atua Wera taught that heaven was a happy place. There was no cold or hunger. There was plenty of flour, sugar, guns, and ships.

Education

Māori knew about schooling in traditional times. It was taught by tohunga (experts). Bishop Selwyn took adult Māori to Sydney. There, they had some schooling to learn English. When missionaries arrived in the Bay of Islands, they realized they needed schools. This was to introduce Christianity and change practices they saw as wrong. Both missionaries and their wives built schools. They provided slates and Bibles for reading. The first school was set up by T. Kendal in 1816. Some adults went to school. But most students were the sons or daughters of chiefs or other important people.

By 1853, Mr and Mrs Ashwell had been running a mission school in the Waikato for 50 Māori girls for three years. The girls learned arithmetic and reading. In the early 1860s, Governor Grey provided money for a trade school near Te Awamutu in the Waikato. The goal was to train Māori workers who could read and write. They would also work with and fix farm machinery. In 1863, Rewi Maniapoto attacked and burned down the school. He stole the printing press. He wanted to kill leading Europeans in the area. But they were warned by friendly Māori and left before the attack. Because of bad influences, the school had poor attendance before this. Only about 10 boys attended regularly. All teaching by missionaries was in Māori. This continued in native schools until 1900. Then, at the request of Māori MPs from the Young Māori Party, schools started teaching in English. Influential Māori MPs Ngata and Pōmare wanted Māori to learn modern ways. They supported the Suppression of Tohungaism Act in parliament. Pōmare worked hard to ban old Māori practices that caused harm in the Māori community.

Food

Traditional Māori Foods

Eating shellfish like mussels and oysters was very common. In summer, sea fish like kahawai were caught. They used bone or mangemange hooks, two-piece lures, or large flax nets. In creeks and lakes, many eels were caught. This happened when they migrated along known waterways using hinaki, a long cone-shaped net. Birds like ducks were hunted during their moulting season. Young birds like petrels and gannets were taken from nests. They were cooked in their own fat to preserve them. Such preserved birds were favorite gifts to fulfill social gift duties. Māori watched nature closely to use seasonal opportunities. Native pigeons ate Miro berries, which made them thirsty. Māori carved wooden bowls with many neck snares. They placed these in Miro trees to catch these large birds.

Evidence from recent digs shows that local shellfish and fish bones were most common in food waste. Dog (kurī) bones and rat bones were next. Less common were bones from small birds and sea mammals. These sites were used from 1450 to 1660 AD, well into the Classical period. The coastal sites showed that Māori had made soils in the sand dunes. These ranged from small to very large areas. The natural soil had been changed by adding dark, rich soil near the surface. This was common where kūmara was grown. In many cases, sand, gravels, and pumice were mixed with rich soil. Kūmara grow slowly in New Zealand's climate. They need well-drained soil. In Eastern Golden Bay, north-facing slopes were preferred.

The warmer climate of the north allowed better growth of subtropical plants. These included kūmara, yam, and gourds. In Auckland and on Mayor Island, volcanic land was cleared of rocks. These rocks were used for low shelter walls. In some areas, piles of volcanic rock stayed warm at night. They were used to train gourd vines.

Many special methods were created to grow and store kūmara so it wouldn't rot. Careful storage and use of tapu were essential to prevent unauthorized use. Seed kūmara were especially tapu. The main problem for kūmara growers was native caterpillars. Early European explorers reported that Māori often circled a garden with burning plants. This was to try and control caterpillars. Māori continued to eat traditional fern roots (aruhe) as a normal part of their diet into the mid-19th century.

Introduced Foods

The arrival of European foods changed many parts of Māori farming. Traditionally, Māori farmland was left after a few crops. This was because production went down. This was the usual pattern, except for a few very fertile river valleys. Fertilizer was not used. But Māori had found ways to improve production. For example, they added pumice to improve drainage on heavy soils. Māori let gardens return to shrubs. Plantations were moved to other areas. The introduction of foreign weeds was a big problem from the 1820s. But this was balanced by the widespread growth of the introduced potato. The traditional types of these potatoes are still grown and known as taewa or Māori potatoes.

European farms and their methods attracted Māori in the North. Later, this happened in the Te Awamutu area of the Waikato. With missionary help, Māori learned to mass-produce food, especially potatoes. They grew far more than they needed for trading until the late 1850s. In 1858, European numbers equaled Māori numbers. More and more, European farmers could supply towns like Auckland. At the same time, the strong demand for food to supply gold rush markets in Australia and California ended.

Trade and Travel

Transport

The usual Māori way to travel was on foot. The North Island had a large network of single-lane tracks. These tracks went across beaches, plains, valleys, and mountain passes. Some tracks were used by many tribes and were considered neutral ground. Missionaries who traveled with Māori guides found that canoes were left at river crossings for any traveler to use. Between 1840 and 1850, explorers, artists, and government officials traveled inland with Māori guides. The guides carried heavy loads and would carry Europeans across creeks. Crossing swamps was common. They carried some food but relied on buying basic foods like potatoes or native pigeons from Māori settlements. The most popular payment was tobacco, which was in high demand. In more remote areas, travelers sometimes found Māori living alone. They grew a few potatoes.

Canoes (waka) were used a lot. These ranged from small river boats to large waka taua (war vessels). War vessels could carry up to 80 paddlers and be up to 40 meters long. Waka were used for long-distance travel down the east coast and to cross Cook Strait. In 1822-23, Te Rauparaha explored the upper South Island in waka. He then launched a sea invasion against other tribes. Henry Williams saw as many as 50 waka taua traveling together. But he said they only went to sea in calm weather. From 1835, many European ships entered the Bay of Islands each year. Henry Williams reported an average of 70-80 ships per year. Many Māori men worked on the ships. About eight Māori seamen were on each whaling ship. Ten-meter-long whaleboats began to be used by Māori. They could be rowed and sailed. In the 1850s, Māori developed a large fleet of small trading schooners. All the first European towns were supported by Māori.

During the mid-19th century, Māori in Auckland and Northland controlled shipping trade. In 1851, 51 vessels were registered, and 30 smaller vessels were licensed. By 1857, there were 37 schooners. The fleet grew during the Tasman trade boom of 1853–56. Māori paid customs duties to the government. They invested heavily in vessels. So, they suffered a lot when a big market slump hit New Zealand. This especially affected the Auckland-Waikato-Hauraki area. During the Musket War period, Māori hid in isolated places. They lived off small vegetable gardens. This was common in Taranaki, which had been badly affected by Waikato attacks. European explorers often found these survivors.

Trade

When Europeans arrived, Māori slowly started to trust British money. They began using it to buy and sell things instead of trading goods. This was rare before 1834. But it became more common as more Māori worked as sailors on European ships. They gained a good reputation as strong, capable workers.

By 1839, a large part of Māori trade was paid for in cash. Māori preferred coins over paper money. Northern Māori learned they could hide cash more easily from their relatives. This helped them avoid the traditional sharing of goods with their hapu (family group). From 1835 to 1840, the northern Māori economy changed completely. Māori left many old trading habits and adopted European ones. They became dependent on European goods to maintain their new way of life.

Trading increased the influence of chiefs over their hapu. Northern traders assumed the chief was the leader of the hapu. All trade and payments went through him. This gave chiefs much more influence, especially after 1835, because trade was so regular. In old times, the power of chiefs was not very great. It was mostly limited to leading in warfare. Early European observers noted that at hapu and whanuau hui (meetings), everyone, including women, had their say. The chief had no more influence than anyone else on the final decision. If a chief had great mana and could persuade people, they had more influence because of their personality, not their authority.

Not all tribes had regular contact with Europeans. The French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville visited Tasman Bay in 1827. He could talk to local Māori using what he learned in the Bay of Islands. He found that they knew a little about Europeans and firearms. But their understanding was far less than that of the Northern Māori.

In the Waikato, regular contact did not start until 50 years after contact in the north. It was not until the Ngāti Toa were forced out of Kawhia in 1821 that most of the Tainui people met Europeans. In 1823, a man named Te Puaha visited the Bay of Islands. He brought back Captain Kent, who arrived by ship at Kawhia.

By 1859, trade was the main way Māori interacted with Europeans. Māori expected to control trade. From the first contact, they sold or exchanged fresh food. First, for high-value goods like axes, and later for money. George Grey wanted to encourage Māori trade. He made new laws in 1846 to help them. Māori brought many cases under this law and won. This was their first and most successful legal experience. Māori began to include European ideas into their own culture. In 1886, banknotes were printed (but not issued) by Te Peeke o Aotearoa. This was a bank started by Tāwhiao, the Māori King. The notes had Māori text and a picture of a flax bush. The bank's checks had Māori figures and native birds and plants drawn on them.

Land Negotiations

The Māori relationship with the land is complex. Traditionally, the resources on the land were controlled by systems of mana (power) and whakapapa (ancestral right). The land itself was both sacred and abstract. Often, many groups felt connected to the same important river or mountain. Oral tradition recorded the movements of groups and their connection to an ancestral place.

In the early 19th century, many Europeans dealt with Māori to get land. Some settlers thought they were buying land to own it completely, like freehold title in British law. Māori said that the agreements they signed were more limited. They did not mean giving up the land entirely. It has been argued that the word "tuku" in agreements, meaning to let or allow or give freely, was not the same as selling. This and other ways of understanding early land deals have caused much disagreement.

Māori, especially after 1830, wanted Europeans to live on their land under their protection. This way, they could benefit from European knowledge and trade. Missionaries wanted to buy land so they could grow their own food. This made them less dependent on tribal "protectors," who sometimes used food supplies to pressure them. Settlers allowed Māori to stay on the land they had "bought." They often continued to give gifts to tribal chiefs. This was often at the chiefs' request, to keep friendly relationships. These agreements stopped when the Treaty of Waitangi was signed.

Another reason for Māori to "sell" land to missionaries was to protect the land from other tribes. Māori who had become Christian wanted to protect their land without fighting. Some control passed to the missionaries. Māori trusted them to allow continued access and use of the land.

From 1840, older chiefs were generally unwilling to sell land. But younger chiefs were in favor. The situation was complicated because Māori often had overlapping rights on poorly defined land. The settlers and government also had very few trained surveyors. Even fully owned land boundaries were unclear. Surveying was a new skill and involved hard physical work, especially in hilly areas. New farmers could buy a small farm from Māori. They would build their home and farm buildings there. Then, they would lease much larger areas of land from Māori owners. Short-term leases gave Māori a strong position. There was a high demand for grazing land.

The Native Lands Act was a government policy in 1865. It allowed Māori people to get individual titles for their land to sell. This act ended the traditional shared landholdings. It made it easier for European settlers to buy land directly.

From the late 1840s, some Māori tribes felt that the Crown was not keeping its promises under the Treaty of Waitangi or individual land deals. These claims against the government became a major part of tribal politics. Each generation of leaders was judged by their ability to advance a land claim.

Leadership and Politics

Māori Kingship

When they first arrived in New Zealand, Māori lived in tribes. Each tribe was independent under its own chiefs. But by the 1850s, Māori faced more and more British settlers. They also faced less political power and growing demands from the Crown to buy their lands. From about 1853, Māori began bringing back the old tribal runanga or chief war councils. Land issues were discussed there. In May 1854, a large meeting was held in south Taranaki. As many as 2000 Māori leaders attended. Speakers urged strong opposition to selling land.

Te Rauparaha's son, Tamihana Te Rauparaha, was inspired by a trip to England where he met Queen Victoria. He used the runanga to promote the idea of forming a Māori kingdom. One king would rule over all tribes. The kotahitanga or unity movement aimed to bring Māori the unity that Europeans clearly had. It was believed that having a monarch like Queen Victoria would let Māori deal with Pākehā (Europeans) as equals. It also aimed to create a system of law and order in Māori communities. The Auckland government had shown little interest in this so far.

Several North Island leaders were asked to become king but declined. But in February 1857, Wiremu Tamihana, a chief from the Ngāti Hauā tribe, suggested the elderly and high-ranking Waikato chief Te Wherowhero. Despite his first doubts, he was crowned at Ngaruawahia in June 1858. He later took the name Pōtatau Te Wherowhero or simply Pōtatau. People widely respected the movement's efforts to create a "land league" to slow land sales. But Pōtatau's role was strongly supported only by Waikato Māori. Tribes in North Auckland and south of Waikato showed him little recognition. Over time, the King Movement gained a flag, a council, laws, a "King's Resident Magistrate," police, a bank, a surveyor, and a newspaper, Te Hokioi. All this made the movement look like an alternative government.

Pōtatau died in 1860. He was followed by Matutaera Tāwhiao. His 34-year reign happened during the military invasion of the Waikato. This invasion partly aimed to crush the Kingitanga movement. The government saw it as a challenge to the British monarchy. Five Māori monarchs have held the throne since then. This includes Dame Te Atairangikaahu, who reigned for 40 years until her death in 2006. Her son Tūheitia is the current king. Old traditions like the poukai (annual visits by the monarch to marae) and the koroneihana (coronation celebrations) continue.

Today, the Māori monarch has no legal power from the New Zealand government. But reigning monarchs are still the main chiefs of several important tribes. They have some power over these tribes, especially within Tainui.

Warfare

From the Classical period, warfare was an important part of Māori culture. This continued through the time of European contact. It was shown in the 20th century by many Māori volunteers in the First and Second World Wars. Today, Māori men are a large part of the New Zealand Army, Navy, and private military groups. New Zealand's army is known as its own tribe, Ngāti Tūmatauenga (Tribe of the War God).

Images for kids

-

Taika Waititi at the 2019 San Diego Comic-Con.

-

A Māori war canoe, drawing by Alexander Sporing, from Cook's first voyage, 1769.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |