Huia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids HuiaTemporal range: Holocene

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

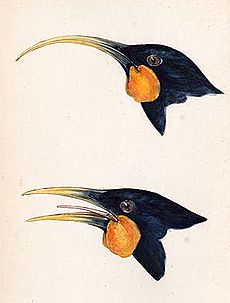

| A pair of huia (male in front of female) Painting by J. G. Keulemans from W. L. Buller's A History of the Birds of New Zealand (1888) |

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Callaeidae |

| Genus: | †Heteralocha Cabanis, 1851 |

| Species: |

†H. acutirostris

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Heteralocha acutirostris (Gould, 1837)

|

|

|

|

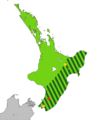

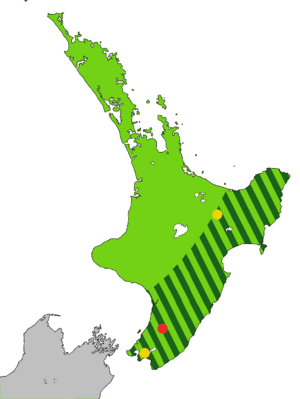

| Light green: original range Dark green stripes: 1840 range Red: site of 1907 last confirmed sighting Yellow: sites of later unconfirmed sightings |

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Neomorpha acutirostris (female) |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) was a beautiful bird that lived only in the North Island of New Zealand. It belonged to a group of birds called New Zealand wattlebirds. Sadly, the last time anyone officially saw a huia was in 1907. However, some people believed they saw them as late as the 1960s.

The huia became extinct mainly for two reasons. First, too many people hunted them. They wanted the huia's skin for stuffed displays and their tail feathers for fancy hats. Second, European settlers cut down huge amounts of forest in the North Island. They cleared the land to make farms. Huia birds needed these old, complex forests to survive. They could not live in the new, younger forests that grew back.

Even before Europeans arrived, the huia was a rare bird. It lived only in certain mountain ranges in the south-east of the North Island. The huia was famous for its beak, which was very different between males and females. This is called sexual dimorphism. The female's beak was long, thin, and curved downwards. The male's beak was short and strong, like a crow's. Males were about 45 cm (18 inches) long. Females were a bit bigger, at 48 cm (19 inches). Both sexes had bright orange wattles (fleshy growths near the beak) and shiny bluish-black feathers. Their tail feathers were special, with a wide white band at the tips.

Huia birds lived in forests both high up in the mountains and down in the lowlands. They might have moved between these areas depending on the season. They ate both insects and fruit. Males and females used their different beaks to find food in different ways. The male would chisel into rotting wood. The female's longer, flexible beak could reach deeper into holes. Even though the huia is famous for its unique beak, scientists did not study it much before it disappeared.

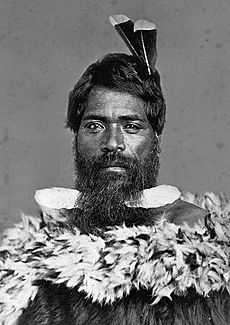

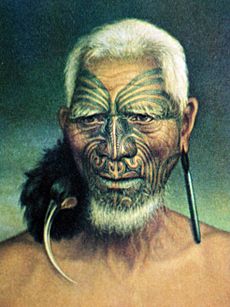

The huia is one of New Zealand's most well-known extinct birds. People remember it for its unique beak, its beauty, and its special place in Māori culture. Māori people thought the bird was tapu (sacred). Only people of high status were allowed to wear its skin or feathers.

Contents

What's in a Name?

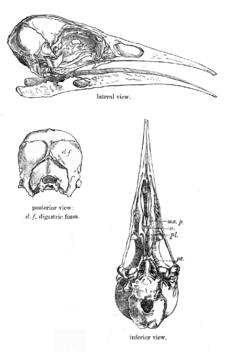

The scientific name for the huia is Heteralocha acutirostris. The name Heteralocha comes from ancient Greek words meaning "different wife". This refers to the big difference in beak shape between the male and female birds. The second part, acutirostris, comes from Latin words meaning "sharp pointed beak". This describes the female's beak.

In 1836, a scientist named John Gould first described the huia. He actually thought the male and female were two different species because their beaks were so unalike! Later, scientists realised they were the same species. The huia is the largest of the three New Zealand wattlebirds. The other two are the saddleback and the kōkako.

Appearance and Unique Beaks

The huia had shiny black feathers with a green shimmer. They had bright orange wattles near their beaks. Their eyes were brown, and their beaks were ivory white with a grey base. Their legs and feet were long and bluish-grey. Huia birds had twelve long, black tail feathers. Each feather had a clear white band about 2.5 to 3 cm (1 to 1.2 inches) wide at the tip. Young huia birds had paler wattles and duller feathers. The white tips on their tail feathers had a reddish tint. Young female huia had only a slightly curved beak.

Some huia were called huia-ariki by Māori. These birds had brownish feathers with grey streaks. Their neck and head feathers were darker. This might have been a type of partial albinism, or perhaps these were very old birds. Some true albino huia (completely white) were also seen.

The huia had the most extreme difference in beak shape between sexes of any bird in the world. The male's beak was about 60 mm (2.4 inches) long. It was strong and slightly curved downwards, similar to the saddleback's beak. The female's beak was thinner and longer, about 104 mm (4.1 inches). It curved downwards like a hummingbird's beak. This difference was not just in the bone. The outer covering of the beak grew far past the bone. This made it flexible and able to reach deep into holes made by beetle larvae.

Scientists have two main ideas about why their beaks were so different. The most popular idea is that it allowed males and females to find different kinds of food. This meant they didn't compete with each other for the same meals. The other idea is that the ivory-coloured beak, which stood out against the black feathers, helped them attract a mate.

Males were about 45 cm (18 inches) long, and females were slightly larger at 48 cm (19 inches). The male's tail was about 20 cm (7.9 inches) long, and his wingspan was 21 to 22 cm (8.3 to 8.7 inches). The female's tail was a bit shorter, 19.5 to 20 cm (7.7 to 7.9 inches), and her wingspan was 20 to 20.5 cm (7.9 to 8.1 inches).

Where They Lived

Old bones and remains show that the huia once lived across the entire North Island of New Zealand. This included both lowland and mountain forests. However, after Māori people settled in New Zealand around 750 years ago, the huia disappeared from the northern and western parts of the island. This was due to hunting, forest clearing, and rats that ate their eggs.

By the time Europeans arrived in the 1840s, the huia was only found in the southern part of the North Island. It lived in broadleaf-podocarp forests, which have many different types of trees and a thick undergrowth. Sometimes, they were also seen in southern beech forests. They were never found in burnt forests or on land cleared for farming.

Life in the Forest

Movements and Feeding

The huia probably stayed in one area for most of its life. It is thought that they moved between mountain forests in summer and lowland forests in winter. This helped them avoid harsh weather and cold temperatures. Like other New Zealand wattlebirds, the huia was not a strong flyer. It could only fly short distances, usually not above the treetops. More often, it used its strong legs to hop and leap through the forest canopy or on the ground. It could also cling to tree trunks.

The huia mainly looked for food in decaying wood. It was known for eating the larvae (grubs) of the huhu beetle, which are large insects that live in wood. But they also ate other insects, spiders, and fruits from native plants.

Huia birds would search for insects and spiders in rotting wood, under bark, in moss, and on the ground. They foraged alone, in pairs, or in small family groups of up to five birds. The male and female used their different beaks to find food in different ways. The male used his strong, chisel-like beak to break open the outer layers of decaying wood. The female's longer, more flexible beak could reach deeper into holes where insect larvae lived, even in living wood. The male had strong head muscles to help him break wood apart.

It was once thought that male and female huia worked together to find food. This idea came from a misunderstanding of a story about captive birds. In reality, their different beaks meant they could find food in different places. This helped them avoid competing with each other for food.

New Zealand forests rely on birds to spread seeds. About 70% of the plants have fruits that birds probably helped to spread. The huia ate fruits from trees like hinau, pigeonwood, and kahikatea. The extinction of the huia and other fruit-eating birds has meant fewer birds are left to spread seeds in the forest. This can affect how well the forest grows back.

Voice and Sounds

We don't know much about the huia's calls. What we do know comes from a few old descriptions. Their calls were mostly a variety of whistles, described as "peculiar and strange" but also "soft, melodious and flute-like." You can even hear a recording from 1909 of a search team member whistling an imitation of the huia's call.

Huia were often quiet. But when they did call, their sounds could travel far, up to 400 meters (1,300 feet) through thick forest. People said the calls were different between males and females, but we don't have many details. They usually called in the early morning. The huia's name itself is a sound word, or onomatopoeic. Māori named it "huia" because of its loud distress call, which sounded like uia, uia, uia or "where are you?". This call was made when the bird was excited or hungry. Young huia chicks had a "pleasant cry" and would respond to people imitating their calls.

Social Life and Reproduction

The huia was a quiet, social bird. They were monogamous, meaning pairs likely stayed together for life. They were usually found in breeding pairs, but sometimes in small groups of four or more, which were probably family groups. People who kept huia as pets noticed that pairs stayed very close. They would make a "low affectionate twitter" sound. There are stories of pairs "caressing each other with their bills" and making these noises. It's thought that the male might have fed the female during courtship. If one bird of a pair died, the other would often die soon after from sadness.

Huia birds were not afraid of people. Females would let people handle them on the nest. Birds could even be caught by hand.

We don't know much about huia reproduction. Only two eggs and four nests have ever been described. The only known huia egg still exists at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. The breeding season was likely in late spring (October–November). They probably nested alone, and pairs stayed in their territory for life.

Huia seemed to raise only one group of chicks per season. They laid between one and five eggs, usually two to four. The eggs were greyish with purple and brown spots, about 45 by 30 mm (1.8 by 1.2 inches). The female did most of the incubation, but the male might have helped a little. The chicks stayed with their family group and were fed by the adults for three months. By then, they looked like adult birds.

Huia and Humans

In Māori Culture

In Māori culture, the huia was not usually eaten. It was a rare bird, highly valued for its beautiful feathers. These feathers were worn by people of high rank. The huia's calm and curious nature made it easy to catch. Māori would attract huia by imitating their call. Then they would catch them using a special pole with a noose or with snares. They also used clubs or long spears. Often, they would catch one bird, and it would call out, attracting its mate, which could then be easily caught too.

Even though the huia only lived in the southern North Island, its tail feathers were very valuable. They were traded among different tribes for other precious items like pounamu (greenstone) and shark teeth. They were also given as gifts of friendship. These feathers were stored in beautifully carved boxes called waka huia, which hung from the ceilings of chiefs' houses. Huia feathers were worn at funerals and used to decorate the heads of the deceased. Special ornaments called pōhoi were made from huia skins, including the beak and wattles. These were worn around the neck or ears. Dried huia heads were also worn as pendants. Sometimes, a captured huia would be kept in a small cage so its tail feathers could be plucked as they grew.

Māori also kept huia as pets. Like the tui, they could be trained to say a few words. European settlers also kept tame huia in the 19th century.

New Zealand has featured the huia on several postage stamps. The New Zealand sixpence coin, made between 1933 and 1966, had a female huia on one side.

Many places in New Zealand are named after the huia. There are roads and streets called Huia Road, especially in Wellington and Auckland. There is even a suburb called Huia in Waitakere. A river on the South Island and the Huiarau Ranges in the North Island are also named after the bird. Huiarau means "a hundred huia," because the birds were once very common there. Businesses like a swimming pool, a winery, and a publishing company also use the name. The name "Huia" is still used today for children, especially girls.

Huia tail feathers are now very rare and valuable to collectors. In 2010, a single huia tail feather sold for NZ$8,000 (about US$5,500) at an auction in Auckland. This made it the most expensive feather ever sold.

In the 2016 New Zealand film Hunt for the Wilderpeople, two characters see a huia and try to find proof of their sighting.

Why the Huia Disappeared

Before humans arrived, the huia lived all over the North Island. After Māori settled in New Zealand, hunting and introduced rats reduced the huia's range. However, Māori hunting was somewhat controlled by traditional rules. The hunting season was only from May to July, when the feathers were best. A rāhui (hunting ban) was put in place during spring and summer.

After European settlers arrived in the 1840s, the huia's numbers dropped much faster. This was mainly due to two reasons: widespread forest clearing and too much hunting.

Huge amounts of forest were cut down in the North Island to create farmland. The huia was very vulnerable to this because it needed old forests with many rotting trees. These trees were full of the insect larvae that huia ate. It seems the huia could not survive in the younger, regrowing forests. Even though the mountain forests were not cut down, the lowland forests in the valleys were destroyed. This loss of habitat would have greatly harmed huia populations. It was especially bad if the birds moved to the lowlands in winter to escape the snow.

New animals brought to New Zealand, like rats, cats, and stoats, also played a part in the huia's decline. These animals were introduced in the 1880s, which was when huia numbers dropped sharply. Because huia spent a lot of time on the ground, they were easy prey for these new predators.

Besides habitat loss and new predators, the huia faced huge pressure from hunting. Its unique beak and beauty made it very popular for wealthy collectors and museums around the world. They paid a lot of money for good specimens. This created a strong reason for hunters in New Zealand to catch huia. For example, an Austrian taxidermist collected 212 pairs over 10 years. A New Zealand scientist collected 18 birds on just one trip. Others joined in to make money. One group of 11 Māori collected 646 huia skins from a forest area in 1883. Thousands of huia were sent overseas. Also, hundreds of huia were shot near new roads and railway lines being built in the forests.

While we were looking at and admiring this little picture of bird-life, a pair of Huia, without uttering a sound, appeared in a tree overhead, and as they were caressing each other with their beautiful bills, a charge of No. 6 brought them both to the ground together. The incident was rather touching and I felt almost glad that the shot was not mine, although by no means loth to appropriate 2 fine specimens.

—Sir Walter Buller, a famous 19th-century New Zealand bird expert, describing how people felt about the declining birds.

The hunting was not just for money. Many Europeans in the 19th century believed that New Zealand's native plants and animals were weaker than European ones. They thought native species would naturally disappear. This idea made people think that trying to save the birds was pointless. So, collectors focused on getting specimens before the rare species vanished forever.

There were some attempts to save the huia, but they were few and not well organised. The idea of protecting nature was very new in New Zealand. Huia numbers dropped sharply in the 1860s and late 1880s. This led Māori chiefs to place a hunting ban on the Tararua Range. In 1892, a law was changed to protect the huia, making it illegal to kill the bird. But this law was not taken seriously.

Bird sanctuaries were set up on islands like Kapiti Island and Little Barrier Island. However, no huia were ever successfully moved to these safe places. Attempts to catch birds for transfer failed. For example, a live pair meant for Kapiti Island in 1893 was instead taken by a scientist to England as a gift for a rich collector.

In 1901, the Duke and Duchess of York (who later became King George V and Queen Mary) visited New Zealand. At a Māori welcome, a guide placed a huia tail feather in the Duke's hat as a sign of respect. Many people in England and New Zealand wanted to copy this royal fashion. The price of huia tail feathers quickly went up. Female huia beaks were also set in gold to make jewellery. In 1901, the huia was no longer listed as a protected species for hunting. A final attempt to protect the feathers failed because there was no law to do so.

The huia disappeared at different rates in different places. Some areas saw big drops in numbers in the 1880s. In the early 1900s, the huia was still common in a few places. A flock of 100–150 birds was seen in 1905. They were still "fairly plentiful" in a river area in 1906. But the last confirmed sighting came just one year later.

The last official sighting of a huia was on 28 December 1907. W. W. Smith saw three birds in the Tararua Ranges. However, some "quite believable" reports suggest the huia might have survived a little longer. A man who knew the species well said he saw three huia in a valley near Wellington Harbour on 28 December 1922. Other sightings were reported there in 1912 and 1913. Sadly, museum scientists did not investigate these reports. The last believable reports of huia come from the forests of Te Urewera National Park. There was one sighting in 1952 and final sightings in 1961 and 1963. Some researchers have suggested that a small group of huia might still exist in the Urewera ranges, but it is considered very unlikely. No recent trips have been made to find a living huia.

In 1999, students at Hastings Boys' High School held a conference to discuss cloning the huia, which was their school's emblem. A Māori tribe agreed to support the idea. However, a bird curator from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa said that the huia's complete DNA could not be recovered from old museum skins. This meant cloning was unlikely to work.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Huia para niños

In Spanish: Huia para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |