Pā facts for kids

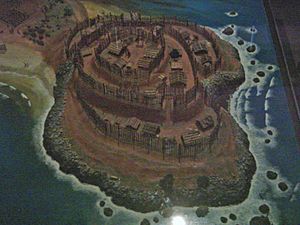

The word pā (often spelled pa in English) refers to a Māori village or settlement. It often means a hillfort, which is a fortified settlement built with strong fences called palisades and defensive terraces. Pā were also built as fortified villages.

Most pā sites are found in the North Island of New Zealand, especially north of Lake Taupō. Over 5,000 pā sites have been found and studied. No pā have been found from the very early days when Polynesian-Māori settlers first arrived in the lower South Island. Similar types of fortified settlements can be found in other parts of central Polynesia, like Fiji, Tonga, and the Marquesas Islands.

In Māori culture, a large pā showed the mana (prestige or power) and smart planning of an iwi (tribe). This was often shown through the rangatira (chieftain) who led the tribe. Māori built pā in easily defended places around their tribal land (rohe). This helped protect their fertile farms and food supplies.

Almost all pā were built on high ground, like volcanic hills. The natural slopes of these hills were then shaped into terraces. Dormant volcanoes were often used for pā in the area where Auckland is today. Pā had many uses. Studies have shown that pā protected food and water storage areas, including wells. They also had food-storage pits (especially for kūmara, a type of sweet potato) and small gardens inside the pā walls.

Recent studies suggest that not many people lived in one pā all the time. Instead, an iwi often had several pā at once, often managed by a hapū (subtribe). The areas between pā were mostly used for homes and farming. If you visit Auckland, you can see an amazing example of pā engineering at Maungawhau / Mount Eden.

Contents

Types of Traditional Pā Designs

Traditional pā came in many different designs.

Simple Pā: Tuwatawata

The simplest pā was called a tuwatawata. It usually had a single wooden palisade (a strong fence made of pointed logs) built around the village stronghold. It also had several raised platforms from which defenders could fight.

Complex Pā: Pā Maioro and Pā Whakino

A pā maioro was built with multiple earth walls called ramparts. It also had ditches that could be used for hiding and ambushes, along with many rows of palisades.

The most advanced pā was known as a pā whakino. These included all the features of other pā, plus more food storage areas and wells for water. They had more terraces, ramparts, palisades, and fighting platforms. Some even had outpost platforms, underground dug-outs, and mountain or hill summits called "tihi." These summits were protected by multiple palisade walls with secret underground passages for communication or escape. Pā whakino also featured beautifully carved entrance ways and main posts.

An important difference between Māori pā and British forts was that pā included food storage pits. Some pā were even built just to keep food safe. Pā were built in many different locations, including volcanoes, spurs (ridges of land), headlands (narrow pieces of land sticking out into the sea), ridges, peninsulas, and small artificial islands.

Inside a Pā

Standard features of a pā included a community well for water, special areas for waste, and an outpost or raised platform on the summit. On this platform, a pahu would be hung. A pahu was a large, oblong piece of wood with a groove in the middle. When a heavy piece of wood was struck from side to side of the groove, it made a sound to warn residents of an attack.

The whare (a Māori dwelling or hut) of the rangatira (chief) and ariki (high chief) were often built on the summit, along with a place to store weapons. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the taiaha (a long, flat weapon) was the most common weapon. The chief's stronghold on the summit could be larger than a normal whare, sometimes measuring 4.5 meters by 4 meters.

Tools and Weapons

Archaeological digs at pā sites in Northland have given us many clues about how Māori made tools and weapons. They found evidence of making tools from obsidian (volcanic glass), chert, argillite basalt, and flakes. They also found pounamu (greenstone) chisels, adzes, weapons made from bone and ivory, and many different hammer tools that had been collected over hundreds of years.

Chert, a smooth stone that is easy to shape, was the most common stone used. Thousands of pieces have been found in some Northland digs. Small pieces or flakes of chert were used as drills for building pā and for making other tools like Polynesian fish hooks. Another discovery in Northland pā studies was the use of "kokowai," or red ochre. This is a red dye made from red iron or aluminum oxides, which is finely ground and then mixed with an oily substance like fish oil or plant resin. Māori used this mixture to keep insects away in pā built on more difficult platforms during war. This mixture is still used today on whare and waka (canoes) to protect the wood from drying out.

Food Storage and Homes

Studies of pā showed that on the lower terraces, there were semi-underground whare (huts) about 2.4 meters by 2 meters. These were used for storing kūmara. These storage huts had wide racks to hold hand-woven kūmara baskets at an angle, so water would drain off.

These storage whare also had internal drains to remove water. In many pā, kūmara were stored in special pits called rua. The whare of common or lower-ranking Māori were on the lower or outer land, sometimes partly dug into the ground by 300-400mm.

On the lower terraces, you would find the ngutu (entrance gate). This gate had a low fence that forced attackers to slow down and take an awkward high step. The entrance was usually watched over by a raised platform, making attackers very vulnerable.

Most food was grown outside the pā. However, in some higher-ranking pā designs, there were small terraced areas to grow food inside the palisades. Guards were stationed on the summit during times of danger. The blowing of a polished shell trumpet or banging a large wooden gong would signal an alarm. In some pā built in rocky areas, large boulders were used as weapons.

Some iwi, like Ngāi Tūhoe, did not build pā in early times. Instead, they used forest locations for defense, attack, and refuge. These were called pā runanga. Lady Aileen Fox, a leading British archaeologist, noted in 1976 that there were about 2,000 hillforts in Britain. She said New Zealand had twice that number, but further work has since found over 5,000 known pā.

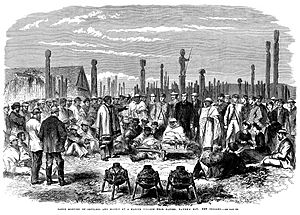

Pā played a very important role in the New Zealand Wars. They are also known from earlier periods of Māori history, going back about 500 years. This suggests that as Māori iwi grew in power and competed for resources and land, warfare became more common, leading to the development of pā.

How Pā Were Fortified

The main defense of pā was the use of earth ramparts (or terraced hillsides), topped with stakes or woven barriers. Later versions of pā were built by Māori fighting with muskets and close-combat weapons (like spears, taiaha, and mere). They were fighting against the British Army and armed constables, who had swords, rifles, and heavy artillery like howitzers and rocket artillery.

Simpler "gunfighter pā" from the period after Europeans arrived could be built very quickly, sometimes in just two to fifteen days. However, the more complex classic pā took months of hard work and were often rebuilt and improved over many years.

The usual ways to attack a classic pā were:

- A surprise attack at night when defenses were not fully manned.

- A siege, where attackers would surround the pā and wait for the defenders to run out of food.

- Using a device called a Rou. This was a half-meter piece of strong wood attached to a thick rope made from raupō leaves. The Rou was slipped over the palisade and then pulled by a team of warriors until the wall fell.

Gunfighter pā could withstand heavy shelling for days with few casualties. However, the loud noise and constant attack usually made defenders leave if the attackers were patient and had enough ammunition. Some historians have mistakenly said that Māori invented trench warfare. But serious military earthworks were first used by French military engineers in the 1700s and were widely used in the Crimean War and the American Civil War. Māori's great skill at building earthworks came from their traditional pā, which by the late 18th century already involved a lot of earthworks for food storage pits (rua), ditches, earth ramparts, and many terraces.

Gunfighter Pā Design

Warrior chiefs like Te Ruki Kawiti understood that these strong defenses could counter the British's greater firepower. With this in mind, they sometimes built pā specifically for defense, like at Ruapekapeka. This was a new pā built to draw the British away, rather than to protect a specific village. At the Battle of Ruapekapeka, the British had 45 casualties, while the Māori had only 30. The British learned from their mistakes and listened to their Māori allies. The pā was shelled for two weeks before it was successfully attacked. Hone Heke won the battle, and the British never tried to put the flagstaff back up at Kororareka while Kawiti was alive. Afterward, British engineers studied the fortifications, made a model, and presented the plans to the British Parliament.

The defenses of such a purpose-built pā included palisades made of hard puriri tree trunks, sunk about 1.5 meters into the ground. They also used split timber and bundles of protective flax padding in later gunfighter pā. Two lines of palisades covered a firing trench with individual pits, while more defenders could use the second palisade to fire over the heads of those below. Simple communication trenches or tunnels were also built to connect different parts, as seen at Ohaeawai Pā or Ruapekapeka. These forts could even have underground bunkers, protected by a thick layer of earth over wooden beams. These bunkers sheltered the people inside during heavy artillery shelling.

One challenge for Māori fortifications that were not permanent was that the people living in them often needed to leave to grow food or gather it from the wilderness. Because of this, pā would often be left empty for 4 to 6 months each year. In Māori tradition, a pā would also be abandoned if a chief was killed or if a disaster happened that a tohunga (spiritual expert) believed was caused by an evil spirit (atua). In the 1860s, Māori, even though many were Christian, still followed parts of their traditional customs (tikanga). Normally, once the kūmara were harvested in March–April and stored, the inhabitants could live a more traveling lifestyle, trading or gathering other foods for winter. However, this did not stop wars from happening outside this time if the desire for utu (payback) was strong. For Māori, summer was the usual fighting season. This put them at a big disadvantage against the British Army, which had good supplies and could fight effectively all year round.

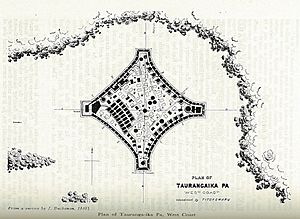

Swamp Pā

Fox noted that pā built near lakes were quite common inland, for example, in the Waikato region. These were often built for whānau (extended family) groups. The land was often flat, but a headland or spur location was preferred. The side facing the lake was usually protected with a single row of palisades, but the landward side was protected by a double row.

Mangakaware swamp pā in Waikato covered about 3400 square meters. Archaeologists found 137 palisade post holes, suggesting there were likely about 500 posts in total. It had eight buildings inside the palisades; six were identified as whare, the largest being 2.4 meters by 6 meters. One building was possibly a cooking shelter, and the last was a large storehouse. There was also a rectangular structure, 1.5 meters by 3 meters, just outside the swamp-side palisades. This was most likely a drying rack or another storehouse. Swamps and lakes provided eels, ducks, weka (swamp hen), and sometimes fish.

The largest swamp pā of this type was found at Lake Ngaroto in Waikato, an ancient settlement of the Ngāti Apakura tribe, very close to the battle of Hingakaka. This pā was built on a much larger scale. Many carved wooden artifacts were found preserved in the peat (a type of soil). These are now on display at the nearby Te Awamutu museum.

Kaiapoi is another famous example of a pā that used a swamp as a key part of its defense.

Examples of Pā Sites

- The old pā remains on One Tree Hill, near the center of Auckland, are one of the largest known sites. It is also one of the largest prehistoric earthwork fortifications found anywhere in the world.

- Pukekura at Taiaroa Head, Otago, was built around 1650 and was still used by Māori in the 1840s.

- Rangiriri (Waikato) was a gunfighter pā built in 1863 by Kingites (supporters of the Māori King Movement). This pā looked like a very long trench running east to west between the Waikato River and Lake Kopuera, with swampy edges. At the highest point, there were strong earthworks with trenches and protective walls. The pā was attacked by bombs from ships and land using Armstrong Guns.

- Nukuhau pā, on the Waikato River near Stubbs Road, is shaped like a triangle. It was built on a flat, raised spur with the Waikato River on one side (200 meters long). A gully with a stream ran along the long west side (200 meters long), and two man-made ditches were on the narrower southern side (107 meters long). The average slope down to the river is 12 meters at an angle of 70 degrees.

- Huriawa, near Karitane in Otago, was built on a narrow, jagged, and easily defended peninsula in the mid-18th century by the Kai Tahu chief Te Wera.

See also

In Spanish: Pa (Maorí) para niños

In Spanish: Pa (Maorí) para niños