Ruapekapeka facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Ruapekapeka |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Flagstaff War | |||

|

|||

| Belligerents | |||

| Māori | |||

| Commanders and leaders | |||

| Royal Navy: Royal Marines; Sailors from HMS Castor, HMS Racehorse, HMS North Star, HMS Calliope East India Company: HEICS Elphinstone British Army: Lieutenant Colonel Henry Despard, 99th Regiment. 58th Regiment ~ 10 officers and 200 men; 99th Regiment ~ 7 officers and 150 men; Board of Ordnance: Captain William Biddlecomb Marlow, Commanding Royal Engineer Auckland Militia: Captain Thomas Ringrose Atkyns. Volunteers ~ 42 men Tāmati Wāka Nene ~ 450 warriors |

Te Ruki Kawiti ~ 150 warriors Hōne Heke ~ 150 warriors |

||

Ruapekapeka is a historic Māori fort located about 20 kilometers (12 miles) southeast of Kawakawa in the Northland Region of New Zealand. It is known as one of the largest and most complex forts ever built by Māori. The Ngāpuhi people designed it specifically to defend against the powerful cannons used by British forces. You can still see the remains of its earthworks today.

Ruapekapeka was the site of the final battle in the Flagstaff War, which took place from 1845 to 1846. This war was fought between the British Colonial forces and the Ngāpuhi Māori, led by chiefs Hone Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti. It was the first major armed conflict between the Colonial government and the Māori.

Contents

What Was Ruapekapeka Pā Like?

This war fort was named Ruapekapeka, which means "bats' nests." This name came from the pihareinga, or dugouts. These were underground shelters with narrow, round entrances at the top. They protected warriors from cannon fire. These ruas, or caves, looked like a calabash buried in the ground, with the narrow part sticking up. Each one could hold 15 to 20 warriors.

How Was Ruapekapeka Pā Designed?

Te Ruki Kawiti and his allies, including Mataroria and Motiti, designed Ruapekapeka Pā. They improved on an earlier fort style called the "gunfighter pā," which was used at the Battle of Ohaeawai. Ruapekapeka was built in 1845 in a strong defensive spot. It was placed far from towns and people, in an area that wasn't important for trade or travel. This was a direct challenge to British rule.

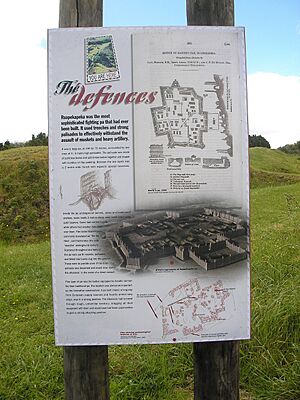

Defenses of the Pā

The outer walls of the fort had deep trenches, called parepare, both in front of and behind the main fences. These fences, or palisades, were 3 meters (10 feet) high and made from strong puriri logs. After muskets were introduced, Māori learned to cover the outside of the palisades with layers of flax leaves. This made them bulletproof, as the flax absorbed the force of musket balls.

Some parts of the fort had three rows of palisades, while others had two. Passages between the front and back trenches allowed warriors to move forward to shoot and then quickly return to safety to reload. On a high point, an observation tower was built to watch for enemies. At the back of the fort, a well about 5 meters (16 feet) deep was dug into sandstone. This provided water during the expected siege of the fort.

The Battle of Ruapekapeka Pā

When the new British Governor, Sir George Grey, could not end the Flagstaff War through talks, he gathered a large British force. This force of 1,168 men was in the Bay of Islands, ready to fight Hone Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti. In early December 1845, the Colonial forces, led by Lieutenant Colonel Despard, traveled by water towards Ruapekapeka. They then spent two weeks moving their heavy cannons over 20 kilometers (12 miles) to reach the fort.

British Artillery and Attack

The British used several powerful cannons in the battle. These included three large 32-pounder naval guns, one 18-pounder, and two 12-pounder howitzers. They also had a 6-pounder brass gun, four 5½-inch brass mortars, and two rocket-tubes. It took two weeks to get these heavy guns close enough to the fort. The cannon attack began on December 27, 1845.

The British bombardment was very accurate, causing much damage to the palisades. However, the Māori inside the fort were safe in their underground shelters. The British began an incomplete siege on December 27, 1845. They did not have enough soldiers to completely surround the fort. Several weeks of siege, with small fights, followed.

Who Fought in the Battle?

The Colonial forces included soldiers from the 58th Regiment and the 99th Regiment. They were joined by 42 volunteers from Auckland. Tāmati Wāka Nene, Eruera Maihi Patuone, Tawhai, Repa, and Nopera Pana-kareao led about 450 Māori warriors who supported the Colonial forces.

The soldiers were also supported by the Royal Marines and sailors from several British ships. These ships included HMS Castor, HMS Racehorse, HMS North Star, and HMS Calliope. The 18-gun sloop HEICS Elphinstone from the Honourable East India Company also took part.

The Māori defenders had a ship's deck-cannon and a field gun. However, a British marine-gunner hit the deck-cannon directly after just three shots, making it useless. The Māori also had limited supplies of gunpowder, so these guns did not help them much. The Māori were mainly armed with double-barrel muzzle-loading muskets, flintlock muskets, and some pistols.

The Fall of the Pā

The siege continued for about two weeks, with small skirmishes to keep everyone alert. Then, early on Sunday, January 11, 1846, William Walker Turau, the brother of Eruera Maihi Patuone, noticed something strange. The fort seemed to be empty. However, Te Ruki Kawiti and a few of his warriors were still inside and appeared surprised by the British attack.

A small group of British troops climbed over the palisade and entered the fort, finding it mostly empty. More British soldiers quickly joined them. Meanwhile, Māori tried to get back into the fort from the rear. After a four-hour gunfight, the remaining Māori left the fort. Lieutenant Colonel Despard called this a "brilliant success."

The "Official Despatches" on January 17, 1846, reported that British forces had 3 soldiers killed and 11 wounded. Also, 2 marines were killed and 10 wounded, and 9 sailors were killed and 12 wounded. Other reports give slightly different numbers. The number of Māori casualties is not known for sure. Heke and Kawiti later said they had lost about 60 people during the entire campaign.

Later, experts examined the fort and found it was very well designed and strongly built. In different situations, it could have held out against a long and costly siege. Lieutenant Balneavis, who was part of the siege, wrote in his diary on January 11:

Pa burnt. Ruapekapeka found a most extraordinary place,--a model of engineering, with a treble stockade, and huts inside, these also fortified. A large embankment in rear of it, full of under-ground holes for the men to live in; communications with subterranean passages enfilading the ditch. Two guns were taken,--a small one, and an 18-pounder, the latter dismantled by our fire. It appeared that they were in want of food and water. It was the strongest pa ever built in New Zealand.

Why Was the Pā Empty?

There is still debate about why the defenders seemed to have left the fort and then tried to re-enter it. One idea is that most of the Māori were at church. Many of them were devout Christians and did not expect an attack on a Sunday. Reverend Richard Davis wrote in his diary on January 14, 1846:

Yesterday the news came that the Pa was taken on Sunday by the sailors, and that twelve Europeans were killed and thirty wounded. The native loss uncertain. It appears the natives did not expect fighting on the Sabbath, and were, the great part of them, out of the Pa, smoking and playing. It is also reported that the troops were assembling for service. The tars, having made a tolerable breach with their cannon on Saturday, took the opportunity of the careless position of the natives, and went into the Pa, but did not get possession without much hard fighting, hand to hand.

However, some historians doubt this explanation. They point out that fighting had happened on a Sunday during the Battle of Ohaeawai in July 1845. Other historians suggest that Heke might have deliberately left the fort to set a trap in the surrounding bush. This would have given Heke a big advantage. In this idea, Heke's ambush only partly worked. Kawiti's men, worried their chief might be in danger, returned towards the fort. The British forces then fought the Māori rebels right behind the fort.

What Happened After the Battle?

It was a Māori custom that a place where a battle had been fought and blood was spilled became sacred or forbidden. Because of this, the Ngāpuhi people left Ruapekapeka Pā. After the battle, Kawiti and his warriors, carrying their dead, traveled about 4 miles (6.4 km) northwest to Waiomio. This was the traditional home of the Ngāti Hine tribe.

After the Battle of Ruapekapeka, Kawiti said he wanted to keep fighting. However, both Kawiti and Heke made it known that they would end the rebellion if the Colonial forces left Ngāpuhi land.

Tāmati Wāka Nene helped as a go-between in talks with Governor Grey. At this time, Governor Grey faced new threats of rebellion in the south. He also would have had trouble supplying his troops for a long fight against Heke and Kawiti. Governor Grey agreed with Tāmati Wāka Nene that being forgiving was the best way to keep peace in the North. Heke and Kawiti were pardoned, meaning they were forgiven, and no land was taken from them.

Lieutenant H. C. Balneavis of the 58th Regiment created a model of Ruapekapeka pā. This model was part of the New Zealand display at The Great Exhibition in London in 1851.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |