Flax in New Zealand facts for kids

New Zealand flax refers to two common New Zealand plants: Phormium tenax and Phormium colensoi. The Māori people call them harakeke and wharariki. Even though they are called 'flax', they are very different from the flax plant found in other parts of the world (like Linum usitatissimum).

P. tenax grows naturally in New Zealand and Norfolk Island. P. colensoi is only found in New Zealand. Both plants have been very important in the history of New Zealand, both for the Māori people and for European settlers who arrived later.

Today, these plants are grown all over the world in places with similar climates. People use them as beautiful garden plants. Some also grow them to make fiber.

Contents

How Māori Used New Zealand Flax

Making Clothes and Textiles

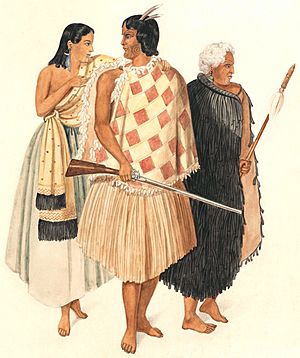

The Māori people used many plants for textiles. But harakeke and wharariki were the most important. This was because they were easy to find, had long fibers, and could be made into different widths. Captain Cook wrote that Māori used these leaves to make all their everyday clothes. They also made strings, lines, and ropes from them.

Māori also made baskets, mats, and fishing nets from raw flax. They were very skilled at weaving cloaks from flax fibers.

Māori recognized almost 60 types of flax. They even grew their own flax in special nurseries. To get the fiber, leaves were cut near the bottom of the plant. They used sharp mussel shells or special stones like greenstone (pounamu). The green, soft part of the leaf was scraped off. This left the strong fiber, which was called muka.

The muka fiber was then washed, pounded, and squeezed by hand. This made it very soft for clothing. It was hard to dye harakeke fibers. However, a special iron-rich mud called paru could dye the fabric black. These muka cords formed the base for beautiful cloaks (kākahu). Some of the most special cloaks were feather cloaks (kahu huruhuru). Different cloaks, like kahu kiwi, were decorated with colorful feathers from native birds. These included kiwi, kaka (parrot), tui, huia, and kereru (woodpigeon).

Other Uses for Flax Fibers

Māori used flax fibers of different strengths for many things. They made eel traps (hinaki) and large fishing nets (kupenga). They also made lines for fishing, bird snares, and ropes. Baskets (kete), bags, mats, clothing, and sandals (paraerae) were also made. They even made buckets, food baskets (rourou), and cooking tools.

The handmade flax ropes were so strong that they were used to tie together parts of hollowed logs. This created huge ocean-going canoes (waka). With these canoes, Māori used seine nets that could be over a thousand meters long. These nets were woven from green flax. They had stone weights and light wood or gourd floats. Hundreds of men were needed to pull them.

Flax was also used for boat rigging, sails, and long anchor ropes. It was even used for roofs on houses. The ends of flax leaves were frayed to make torches for night. The dried flower stalks are very light. They were tied together with flax twine to make river rafts called mokihi.

Flax for Medicine and Healing

For hundreds of years, Māori used the sweet liquid (nectar) from flax flowers as medicine and a sweetener. They boiled and crushed harakeke roots. This paste was put on boils, tumors, and skin problems. Juice from pounded roots was used as a disinfectant. It was also taken to help with constipation or to get rid of worms.

Pounded flax leaves were used as bandages for wounds from bullets or bayonets. The sticky sap from harakeke has special qualities. It helps blood clot and fights germs, which helps wounds heal. It also acts as a mild pain reliever. Māori traditionally put the sap on boils, wounds, aching teeth, and skin problems. They also used it for burns.

Splints for broken bones were made from the flower stalks (korari) and leaves. Fine cords of muka fiber were used to stitch wounds. The gel from flax helped stop bleeding. Harakeke was used like bandages and could hold broken bones in place, much like plaster casts today.

Scientists have found chemicals in flax that fight fungus, reduce swelling, and act as a laxative.

Flax in Defense

During the Musket Wars and later New Zealand Wars, Māori used thick flax mats. These mats covered entrances and lookout holes in their forts, called "gunfighter's pā". Some warriors wore coats made of tightly woven Phormium tenax. These coats were like medieval padded armor. They could slow down musket balls, making them less deadly.

Later Uses by Europeans

By the early 1800s, people around the world knew about the high quality of rope made from New Zealand flax. The Royal Navy (British navy) was a big customer. The flax trade grew a lot. Māori men, who had not worked with flax before, started helping with harvesting and processing it. They saw the benefits of trading.

Māori needed muskets and ammunition. So, many moved to swampy areas where flax grew. They spent so much time on flax production that they didn't grow enough food. This continued until they had enough muskets, ammunition, and iron tools. The need for workers also led to an increase in taking slaves, who were then put to work processing flax.

A large flax industry developed. The fibers were used for rope, twine, mats, carpet padding, and wool sacks. At first, people harvested wild flax. But soon, flax farms were started. By 1851, there were three flax plantations.

In 1870, a government report looked at all parts of the flax industry. It listed up to 24 different types of flax.

People have also looked into using New Zealand flax fiber to make paper. But today, it is mostly used by artists and craftspeople to make special handmade papers.

Flax Mills and Factories

From about the 1860s, there was a busy industry harvesting and processing flax for export. It reached its highest point in 1916, with 32,000 tons of flax. But the economic downturn of the 1930s caused this trade to almost disappear. In 1963, there were still 14 flax mills. They produced almost 5,000 tons of fiber each year. However, the last of these mills closed in 1985.

In 1860, Purchas and Ninnis received the first patent for a flax machine in New Zealand. This machine could process a ton of leaves a day. It produced about 200 kilograms of fiber. A large mill in Halswell had six of these machines by 1868. Another inventor, Johnstone Dougall, also created a flax-stripping machine around 1868. He used it in his first mill at Waiuku.

Many others patented their own versions of flax machines. But the main idea was the same: leaves were fed between rollers. Then, iron beaters, spinning faster than the rollers, hit the leaves. This stripped the outer layer (epidermis) from the fiber.

Flax was very profitable during good times. In 1870, a news report said that one acre of flax, with two harvests a year, could produce two tons of fiber. This could earn £40 a year in profit.

These new machines were quickly adopted. The number of flax mills grew from 15 in 1867 to 110 in 1874. By 1870, there were 161 mills, employing 1,766 people. A & G Price built almost 100 flax machines in 1868. By August 1869, they had sold 166. Machine-stripped flax was rougher than hand-stripped flax. But by 1868, machines could produce about 250 kilograms per day. This was much more than the 1 kilogram produced by hand. By 1910, improvements increased this to 1.27 tonnes a day.

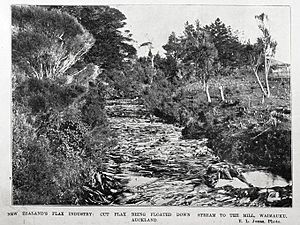

Flax leaves were cut, tied in bundles, and taken to the mill. There, they went through a stripping machine. The slimy fiber was then bundled, washed, and hung to dry. About ten days later, the fiber (muka) was cleaned (scutched) and pressed into bales for shipping. Some mills also had special areas (ropewalks) to make ropes for local use.

Flax production was highest between 1901 and 1918. But plant diseases (rust), the Great Depression, and swamps being turned into pastures led to most mills closing by the 1930s.

Mills were powered by water wheels, small stationary steam engines, or portable engines.

Fires were a big danger for buildings, especially with lots of bush burning and few fire departments. Flax was no different. In 1890, a report about a fire in a large area of growing flax said that most fires were due to carelessness. Many mills also burned down.

By 1890, 3,198 people worked in the flax industry. But their average pay was only £73 a year, which was very low. Workers were also often caught in the machines. At first, companies resisted unions. For example, in an 1891 strike, a mill owner planned to hire new workers from Auckland. However, the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1894 and the growth of unions helped improve low pay and working conditions. By 1913, one person wrote that flax milling used to be done by boys for little pay. But now, a boy could earn a man's wage. For instance, the lowest wage at Mr Rutherford's Te Aoterei mill was 11 shillings 3 pence for a ten-hour day.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |