Tahiti facts for kids

Flag

|

|

|

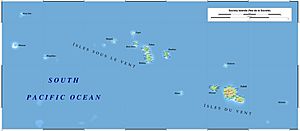

Tahiti, the largest island of the Society islands

|

|

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 17°40′S 149°25′W / 17.667°S 149.417°W |

| Archipelago | Society Islands |

| Major islands | Tahiti |

| Area | 1,044 km2 (403 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,241 m (7,352 ft) |

| Highest point | Mont Orohena |

| Administration | |

|

France

|

|

| Overseas collectivity | French Polynesia |

| Largest settlement | Papeʻete (pop. 136,777) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 189,517 (August 2017 census) |

| Pop. density | 181 /km2 (469 /sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Tahitians |

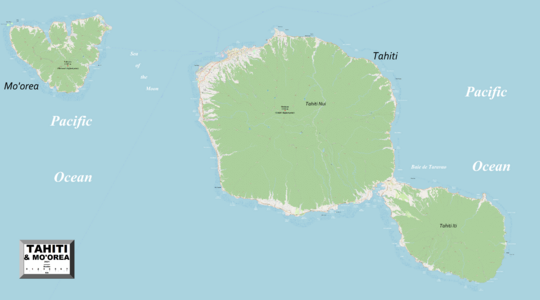

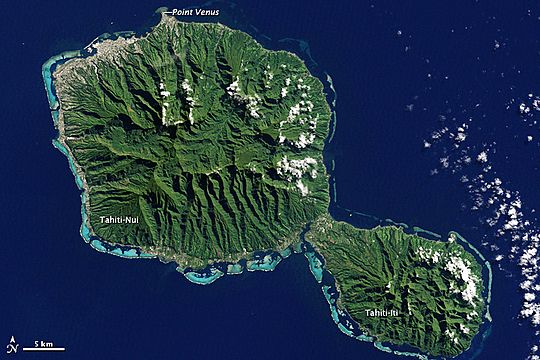

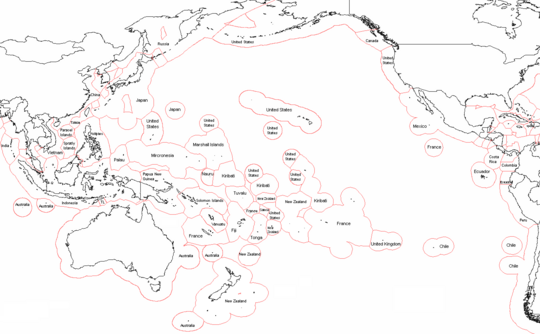

Tahiti is the biggest island in the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It's in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, far from big landmasses like Australia. The island has two parts: Tahiti Nui (the bigger, northwest part) and Tahiti Iti (the smaller, southeast part). Tahiti was made by volcanoes, so it has tall mountains and is surrounded by beautiful coral reefs. In 2017, about 189,517 people lived there, making it the most populated island in French Polynesia.

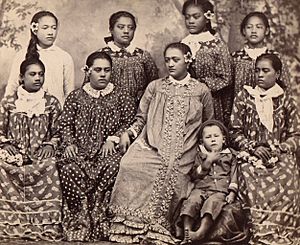

Tahiti is super important for French Polynesia. It's the main place for business, culture, and government. Papeʻete, the capital, is on Tahiti's northwest coast. The only international airport in the area, Faʻaʻā International Airport, is also near Papeʻete. The first people to live on Tahiti were Polynesians, who arrived between 300 and 800 CE. Today, they make up about 70% of the island's population. The rest are people from Europe, China, and those with mixed backgrounds. Tahiti used to be its own kingdom until France took it over in 1880. Then, the people became French citizens. French is the official language, but the Tahitian language (Reo Tahiti) is also spoken a lot.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Discovering Tahiti's Geography

Tahiti is the tallest and largest island in French Polynesia. It's very close to Moʻorea island. Tahiti is about 4,400 kilometers (2,734 miles) south of Hawaiʻi. It's also about 7,900 kilometers (4,909 miles) from Chile. And it's about 5,700 kilometers (3,542 miles) from Australia.

The island is about 45 kilometers (28 miles) wide at its widest point. It covers an area of about 1,045 square kilometers (403 square miles). The highest mountain is Mont Orohena (Mouʻa ʻOrohena), which is 2,241 meters (7,352 feet) tall. Another peak, Mount Roonui (Mouʻa Rōnui), in the southeast, rises to 1,332 meters (4,370 feet).

Tahiti looks like two round parts connected by a small strip of land called the Isthmus of Taravao. The bigger northwest part is called Tahiti Nui ("big Tahiti"). The much smaller southeast part is Tahiti Iti ("small Tahiti"). Tahiti Nui has a lot of people living along its coast, especially around the capital, Papeʻete.

The middle of Tahiti Nui is mostly empty. Tahiti Iti is more isolated. Its southeastern half, called Te Pari, can only be reached by boat or by walking. A main road goes around the rest of the island, between the mountains and the sea. Tahiti has beautiful rainforests, many rivers, and waterfalls. Some famous ones are the Papenoʻo on the north side and the Fautaua Falls near Papeʻete.

How Tahiti's Mountains Were Formed

The Society Islands, where Tahiti is located, were formed by a "hotspot" in the Earth's mantle. This is like a fixed point where hot rock rises. As the Pacific Plate (a huge piece of the Earth's crust) moves over this hotspot, new islands are created. This means the islands get older as you move away from the hotspot.

Tahiti itself was formed by two shield volcanoes, Tahiti Nui and Tahiti Iti. These volcanoes were active between 1.67 million and 0.25 million years ago.

Tahiti's Climate and Weather

Tahiti has a wet season from November to April. January is usually the wettest month. August is the driest month.

The temperature stays pretty warm all year round. It usually ranges between 21 and 31 degrees Celsius (70 and 88 degrees Fahrenheit). There isn't much change between seasons. The lowest temperature ever recorded in Papeʻete was 16 degrees Celsius (61 degrees Fahrenheit). The highest was 34 degrees Celsius (93 degrees Fahrenheit).

| Climate data for Tahiti, 1961-1990 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.3 (86.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.8 (85.6) |

29.5 (85.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.8 (80.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.4 (74.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 315.2 (12.41) |

233.0 (9.17) |

195.3 (7.69) |

140.8 (5.54) |

92.0 (3.62) |

60.2 (2.37) |

60.5 (2.38) |

48.0 (1.89) |

46.3 (1.82) |

90.8 (3.57) |

162.1 (6.38) |

317.0 (12.48) |

1,761.2 (69.32) |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization | |||||||||||||

Tahiti's Rich History

Early Settlers and Their Way of Life

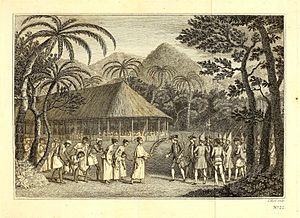

The first people to live in Tahiti came from Western Polynesia. They arrived sometime before 500 BC. They traveled long distances from Southeast Asia. They used large outrigger canoes, which could carry families and animals.

Before Europeans arrived, Tahiti was divided into areas. Each area was controlled by a different family group, called a clan. The most important clans were the Teva i Uta and the Teva i Tai.

Clan leaders included a chief (ariʻi rahi) and nobles (ariʻi). These leaders were also religious figures. They were respected for their mana, which was like spiritual power. They wore special belts made of red feathers to show their power. Decisions, especially about conflicts, were made by councils of leaders.

Each clan had its own marae, which was a stone temple. Priests led the religious practices at these temples.

First European Visitors to Tahiti

The first European to possibly see Tahiti was Juan Fernández in 1576. Another explorer, Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, might have seen it in 1606. However, it's not certain if they actually landed on Tahiti itself.

The first confirmed European visit was by Captain Samuel Wallis. He was sailing around the world in his ship, HMS Dolphin. He saw Tahiti on June 18, 1767. His crew landed in Matavai Bay. At first, there were some difficulties, but peace was made with a local leader named Oberea (Purea).

Then, on April 2, 1768, the French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville arrived. He stayed for about ten days.

Captain James Cook arrived in Matavai Bay on April 12, 1769. He was on a scientific mission to study astronomy and plants. Cook set up a camp at Point Venus for his observatory. His team, including botanist Joseph Banks, gathered lots of information. They learned about Tahiti's animals, plants, society, language, and customs. Cook left Tahiti on July 13, 1769. He thought about 200,000 people lived on Tahiti and nearby islands.

Spain also sent expeditions to Tahiti. In 1772, the Viceroy of Peru sent an expedition. Some Tahitians even traveled back to Peru with the Spanish.

Captain Cook returned to Tahiti in 1773 and again in 1777. He met with many Tahitian clans.

British Influence and the Pōmare Dynasty

The Bounty Mutiny and Its Impact

On October 26, 1788, HMS Bounty arrived in Tahiti. Captain William Bligh was in charge. Their mission was to take breadfruit trees from Tahiti to the Caribbean. The crew stayed for about five months. Three weeks after leaving Tahiti, on April 28, 1789, some of the crew rebelled. This was the famous Mutiny on the Bounty. The mutineers took over the ship. Some of them later returned to live in Tahiti.

These mutineers helped a local chief named Tū. They gave him weapons. Tū used this help to become more powerful on the island. Around 1790, Tū became king and took the name Pōmare. He became Pōmare I, starting the Pōmare Dynasty. This family was the first to unite Tahiti under one rule. They also expanded Tahitian influence to other islands.

In 1791, another British ship, HMS Pandora, came to Tahiti. They captured fourteen of the mutineers.

Whalers and Missionaries Arrive

In the 1790s, whalers started visiting Tahiti. They were hunting whales in the southern oceans. These visits brought big changes to Tahitian society. The sailors brought weapons and new diseases. These interactions caused the Tahitian population to drop quickly. From 16,000 people, it fell to 8,000-9,000 in just ten years.

On March 5, 1797, missionaries from the London Missionary Society arrived. They wanted to convert the local people to Christianity. Their arrival had a lasting impact on Tahitian culture.

The missionaries worked closely with the Pōmare family. In 1803, Pōmare II became king. He learned to read and studied the Gospels from the missionaries. They also encouraged him to unite the island. In 1812, Pōmare II converted to Protestantism. This helped Protestantism spread quickly across Tahiti.

In 1815, Pōmare II won a major battle. This victory made him the king of all Tahiti. It was the first time the island was united under one family. This also meant the end of the old feudal system. Protestantism quickly replaced traditional beliefs. In 1817, the Gospels were translated into Tahitian. In 1818, the city of Papeʻete was founded and became the capital.

In 1819, Pōmare II, with the missionaries' help, introduced the first Tahitian legal code. These laws banned nudity, traditional dances, chants, tattoos, and flower costumes. By the 1820s, almost everyone in Tahiti had converted to Protestantism.

When Pōmare II died in 1821, his son Pōmare III was very young. His uncle and religious leaders ruled for him. In 1824, the missionaries held a coronation for Pōmare III. Local chiefs gained more power during this time. The missionaries also tried to make the Tahitian monarchy more like the English system. They created the Tahitian Legislative Assembly in 1824.

In 1827, Pōmare III died suddenly. His half-sister, Pōmare IV, became queen at age thirteen. She was Protestant and favored England. She often sought England's protection.

In 1835, Charles Darwin visited Tahiti on HMS Beagle. He was impressed by the missionaries' positive influence on the people.

French Protectorate and the End of the Kingdom

In 1836, two French Catholic priests were expelled from Tahiti. In response, France sent Admiral Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars in 1838. He later annexed the Marquesas Islands in 1842. In August 1842, Admiral Du Petit-Thouars returned to Tahiti. He convinced some Tahitian chiefs to ask for French protection. He then made Queen Pōmare sign a treaty. This treaty made Tahiti a French protectorate. France would handle foreign relations and defense. The Queen would manage internal affairs.

There was a struggle for influence between English Protestants and French Catholics. The Protestants kept a strong hold at first.

Conflict and French Control (1844–1847)

In 1843, Queen Pōmare was persuaded to fly the Tahitian flag instead of the French Protectorate flag. In response, Admiral Dupetit-Thouars announced that France was taking over the Kingdom of Pōmare. He set up a governor for the new colony. This led to a conflict between France and Tahiti in March 1844.

The conflict ended in December 1846, with France winning. The Queen returned from exile in 1847. She signed a new agreement that greatly reduced her powers. France now had more control over the Kingdom of Tahiti. In 1863, French Protestant missions replaced the British ones.

Around this time, about a thousand Chinese workers came to Tahiti. They were hired to work on a large cotton plantation. When the plantation failed, many Chinese workers stayed in Tahiti and mixed with the local population.

In 1866, elected district councils were formed. These councils took over the powers of the traditional chiefs. They tried to protect the traditional way of life from European influence.

In 1877, Queen Pōmare died after ruling for fifty years. Her son, Pōmare V, became king. He was not very interested in ruling. In 1880, he agreed to give Tahiti to France. On June 29, 1880, Tahiti became a French colony. All subjects of the Pōmare Kingdom became French citizens. On July 14, 1881, people celebrated Tahiti becoming part of France. In 1890, Papeʻete became a French commune.

The famous French painter Paul Gauguin lived in Tahiti in the 1890s. He painted many scenes of Tahitian life. There is a small Gauguin museum in Papeari.

Tahiti in the 20th Century and Today

In 1903, the French Establishments in Oceania were created. This group included Tahiti and other islands like the Society Islands and Marquesas Islands.

During World War I, two German warships attacked Papeʻete. A French gunboat was sunk. From 1966 to 1996, the French Government conducted 193 nuclear bomb tests near Tahiti. The last test was on January 27, 1996.

In 1946, Tahiti and French Polynesia became an overseas territory of France. Tahitians were given French citizenship.

In 2003, French Polynesia's status changed again. It became an overseas collectivity. In 2004, it was called an overseas country of France.

In 2009, a person named Tauatomo Mairau tried to claim the Tahitian throne in court.

How Tahiti is Governed

Tahiti is part of French Polynesia. French Polynesia is a territory of France that has some self-rule. It has its own assembly, president, budget, and laws. France's role is mainly in providing money, education, and security.

People in Tahiti are French citizens. They have full civil and political rights. French is the official language. However, Tahitian and French are both used. In the 1960s and 1970s, children were not allowed to speak Tahitian in schools. Now, Tahitian is taught in schools. Sometimes, you even need to know Tahitian for a job.

In 2006, French President Jacques Chirac said he didn't think most Tahitians wanted independence. But he said a referendum (a vote by the people) could happen in the future.

Elections for the Assembly of French Polynesia were held on May 23, 2004. A group that wanted independence, led by Oscar Temaru, won by one seat. They formed a government. But in October 2004, the opposing party, led by Gaston Flosse, caused a political crisis.

Who Lives in Tahiti: Demographics

The native Tahitians are of Polynesian background. They make up about 70% of the population. Other people living there include Europeans, East Asians (mostly Chinese), and people of mixed heritage.

In 2017, out of 189,517 residents:

- 75.4% were born in Tahiti.

- 9.3% were born in Metropolitan France.

- 5.9% were born elsewhere in the Society Islands.

- 2.8% were born in the Tuamotu-Gambier islands.

- 1.8% were born in the Marquesas Islands.

- 1.6% were born in the Austral Islands.

- 1.3% were born in other French overseas areas.

- 0.5% were born in East and Southeast Asia.

- 0.3% were born in North Africa.

- 1.1% were born in other foreign countries.

Most people from France live in Papeʻete and its nearby towns. For example, in Punaʻauia, they made up 16.8% of the population in 2017.

Tahiti's Population Over Time

| 1767 | 1797 | 1848 | 1897 | 1911 | 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | 1941 | 1951 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50,000 to 200,000 |

16,000 | 8,600 | 10,750 | 11,800 | 11,700 | 14,200 | 16,800 | 19,000 | 23,100 | 30,500 | ||

| 1956 | 1962 | 1971 | 1977 | 1983 | 1988 | 1996 | 2002 | 2007 | 2012 | 2017 | ||

| 38,140 | 45,430 | 79,494 | 95,604 | 115,820 | 131,309 | 150,721 | 169,674 | 178,133 | 183,645 | 189,517 | ||

| Official figures from past censuses. | ||||||||||||

Tahiti's Local Government

The island of Tahiti is divided into 12 local areas called communes. These communes, along with Moʻorea-Maiao, form the Windward Islands administrative area.

The capital city is Papeʻete. The commune with the most people is Faʻaʻā. The commune with the largest land area is Taiarapu-Est.

Communes of Tahiti: A Closer Look

| Commune | Population | Area | Density | Subdivisions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arue | 9,494 | 21.45 km2 (8.28 sq mi) | 443/km2 (1,150/sq mi) | Tetiaroa, an atoll north of Arue, belongs to this commune. | |

| Faʻaʻā | 29,781 | 34.2 km2 (13.2 sq mi) | 871/km2 (2,260/sq mi) | This is the largest commune in Tahiti and French Polynesia by population. | |

| Hitiaʻa O Te Ra | 8,691 | 218.2 km2 (84.2 sq mi) | 40/km2 (100/sq mi) | Hitiaʻa, Mahaʻena, Papenoʻo, Tiarei | The main town of this commune is Hitiaʻa. |

| Māhina | 14,356 | 51.6 km2 (19.9 sq mi) | 278/km2 (720/sq mi) | It's located near the Papenoʻo River. | |

| Pāʻea | 12,084 | 64.5 km2 (24.9 sq mi) | 187/km2 (480/sq mi) | ||

| Paparā | 10,634 | 92.5 km2 (35.7 sq mi) | 115/km2 (300/sq mi) | ||

| Papeʻete | 26,050 | 17.4 km2 (6.7 sq mi) | 1,497/km2 (3,880/sq mi) | This is the capital of French Polynesia and the second largest city. | |

| Pīraʻe | 14,551 | 35.4 km2 (13.7 sq mi) | 411/km2 (1,060/sq mi) | It's located between Papeʻete and Arue. | |

| Punaʻauia | 25,399 | 75.9 km2 (29.3 sq mi) | 335/km2 (870/sq mi) | French painter Paul Gauguin lived here in the 1890s. Punaʻauia is the third largest city in French Polynesia. | |

| Taiʻarapu-Est | 11,538 | 218.3 km2 (84.3 sq mi) | 53/km2 (140/sq mi) | Afaʻahiti, Faʻaone, Pueu, Tautira | An island called Mehetia also belongs to this commune. |

| Taiʻarapu-Ouest | 7,007 | 104.3 km2 (40.3 sq mi) | 67/km2 (170/sq mi) | Teahupoʻo, Toahotu, Vairao | This commune covers half of the Tahiti Iti peninsula. |

| Teva I Uta | 8,591 | 119.5 km2 (46.1 sq mi) | 72/km2 (190/sq mi) | Mataiea, Papeari | The main town of this commune is Mataiea. |

Tahiti's Economy and Resources

Tourism is a very important part of Tahiti's economy. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, it made up 17% of the island's total income.

Tahiti trades a lot with Metropolitan France. France accounts for about 40% of Tahiti's imports and 25% of its exports. Other important trading partners include China, the US, South Korea, and New Zealand.

Tahitian pearl (Black pearl) farming is another big source of money. Most of these pearls are sent to Japan, Europe, and the United States. Tahiti also sells vanilla, fruits, flowers, monoi (a scented oil), fish, copra oil, and noni (a fruit). Tahiti even has a winery on the Rangiroa atoll.

About 15% of the working population in Tahiti is unemployed. This especially affects women and young people without specific job skills.

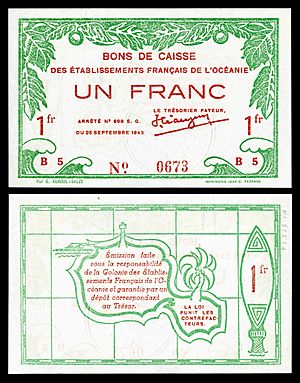

Tahiti uses the French Pacific Franc (CFP or XPF) as its money. This currency is linked to the euro. Hotels and banks can exchange money for visitors.

Tahiti has a sales tax called Taxe sur la valeur ajoutée (TVA), which is like a VAT. In 2009, the VAT was 10% for tourist services and 6% for hotels, guesthouses, food, and drinks. For buying goods, the VAT was 16%.

Energy and Electricity

French Polynesia gets all its petroleum from other countries. It doesn't have its own oil refineries or production. Tahiti uses about 7,430 barrels of imported oil products every day.

Exploring Tahitian Culture

Tahitian culture has a rich oral tradition. This includes stories about gods, like ʻOro, and beliefs. It also includes old traditions like tattooing and navigation. The yearly Heivā I Tahiti Festival in July celebrates traditional culture. It features dance, music, and sports. One sport is a long-distance race between islands using modern outrigger canoes (vaʻa).

The Paul Gauguin Museum is about the life and art of French artist Paul Gauguin. He lived in Tahiti for many years and painted famous works like Two Tahitian Women.

The Musée de Tahiti et des Îles (Museum of Tahiti and the Islands) is in Punaʻauia. It's a museum that collects and protects Polynesian artifacts and cultural practices.

The Robert Wan Pearl Museum is the only museum in the world dedicated to pearls. The Papeʻete Market is a great place to find local arts and crafts.

Traditional Tahitian Dance

One of the most famous things about Tahiti is its traditional dance. The ʻōteʻa is a traditional Tahitian dance. Dancers stand in rows and perform figures. This dance is known for its fast hip-shaking and grass skirts. People sometimes confuse it with the Hawaiʻian hula, which is usually slower and focuses more on hand movements and storytelling.

The ʻōteʻa was one of the few dances that existed before Europeans arrived. Back then, it was mostly a male dance. Today, the ʻōteʻa can be danced by men (ʻōteʻa tāne), by women (ʻōteʻa vahine), or by both genders (ʻōteʻa ʻāmui). The dance is performed only with music from drums, no singing. Drums used include the tōʻere (a wooden log struck with sticks) or the pahu (an ancient standing drum covered with shark skin). A smaller drum, the faʻatete, can also be used.

Dancers use gestures to show everyday life activities. Men might use spears or paddles to act out warfare or sailing. Women's themes are often about home or nature, like combing hair or a butterfly flying. The story of the theme should be clear throughout the entire dance.

The group dance called ʻAparima is often performed with dancers wearing pareo (wrap-around garments). There are two types: the ʻaparima hīmene (sung handdance) and the ʻaparima vāvā (silent handdance), which has music but no singing.

Newer dances include the hivinau and the paʻoʻa.

Beliefs About Death

Tahitians believed in an afterlife, a paradise called Rohutu-noʻanoʻa. When someone died, their body was wrapped in cloth and placed on a special funeral stand. Food was placed nearby for the gods. Mourners would sometimes cut themselves and smear blood on cloth. The Chief Mourner wore a special costume called the parae. This costume had an iridescent mask made of polished pearl shells. It also included red feathers and other shells representing the moon goddess and stars.

Popular Sports in Tahiti

The national sport of Tahiti is Vaʻa, also known as outrigger canoe paddling. Tahitians are often world champions in this sport.

Other major sports include rugby union and association football. Tahiti has a national basketball team that is part of FIBA Oceania.

Surfing is also popular. Famous surfers like Malik Joyeux and Michel Bourez are from Tahiti. Teahupoʻo is known as one of the most challenging surf spots in the world.

Rugby union in Tahiti is managed by the Tahiti Rugby Union. The Tahiti national rugby union team has been playing since 1971.

Football in Tahiti is run by the Tahitian Football Federation. The Tahiti Division Fédérale is the top football league. In 2012, the national team won the 2012 OFC Nations Cup. This allowed them to play in the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup in Brazil. They were the first team from outside Australia or New Zealand to win the OFC Nations Cup.

The Tahiti Cup is the island's main football knockout tournament. The winner plays the winner of the Tahiti Division Fédérale in the Tahiti Coupe des Champions.

In 2010, Tahiti was chosen to host the 2013 FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup.

Tahiti is also very good at Pétanque, a game similar to bocce ball. This is likely due to their strong ties with France.

For the 2024 Summer Olympics, Tahiti will host the surfing competition. This is the only Olympic event that will be held outside of France.

Tahiti in Film

Tahiti is shown in the 2017 French film Gauguin: Voyage to Tahiti. This movie tells the story of painter Paul Gauguin's life on the island.

Many films also tell the story of the 1789 mutiny on HMS Bounty. Examples include Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) with Marlon Brando and The Bounty (1984) with Mel Gibson.

Education and Learning in Tahiti

Tahiti is home to the University of French Polynesia (Université de la Polynésie Française). It is a growing university with 3,200 students and many researchers. Students can study subjects like law, business, science, and literature. There is also a school called Collège La Mennais in Papeʻete.

Getting Around Tahiti: Transport

Air Travel

Faʻaʻā International Airport is about 5 kilometers (3 miles) from Papeʻete. It's the only international airport in French Polynesia. Because there isn't much flat land, the airport was built mostly on land reclaimed from the coral reef.

You can fly to international places like Auckland, Honolulu, Los Angeles, and Tokyo. Airlines like Air France, Air New Zealand, and Air Tahiti Nui (French Polynesia's main airline) fly here.

Flights within French Polynesia and to New Caledonia are available from Aircalin and Air Tahiti. Air Tahiti's main office is at the airport.

Ferry Services

The Moʻorea Ferry runs from Papeʻete to Moʻorea. The trip takes about 45 minutes. Other ferries, like the Aremiti 5 and Aremiti 7, can get you to Moʻorea in about half an hour. There are also several ferries that transport people and goods to other islands. The main place for these ferries is the Papeʻete Wharf.

Roads and Driving

Tahiti has a freeway along its west coast. This freeway starts in Arue and goes through the Papeʻete city area. It then continues along the west coast of Tahiti Nui through smaller villages. The freeway turns east towards Taravao, where Tahiti Nui meets Tahiti Iti. Tahiti's west coast freeway continues until Teahupoʻo, where it becomes a narrower paved road.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tahití para niños

In Spanish: Tahití para niños