Whadjuk facts for kids

The Whadjuk (also called Wadjak or Witjari) are an important group of Noongar people, who are Aboriginal Australians. They traditionally lived in the area around Perth in Western Australia, especially on the Swan Coastal Plain. Their history and culture are deeply connected to this land.

Contents

Whadjuk Name Meaning

The name Whadjuk likely comes from the Noongar word whad, which means "no".

Whadjuk Traditional Country

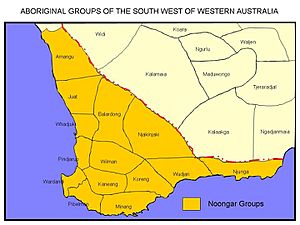

The Whadjuk people's traditional land covered about 6,700 square kilometers (2,587 square miles). This area stretched from the Swan River and its smaller rivers, extending inland towards Mount Helena and York. It included places like Kalamunda and Armadale. To the south, their land reached near Pinjarra. Their neighbors were the Yued to the north, the Balardong to the east, and the Pindjarup along the southern coast.

Whadjuk Culture and Ancient History

The Whadjuk people are part of the larger Noongar language group, but they had their own special dialect. Their culture included a unique social system with two main family groups, called moieties:

- Wardungmat: This group was named after the wardung, which is the Australian raven.

- Manitjmat: This group was named after the manitj, or western corella (a type of parrot).

Children belonged to their mother's moiety. Each moiety also had two smaller "sections" or "skins" that helped organize families and marriages.

The Whadjuk also shared many stories about the Wagyl, a powerful water-python spirit. They believed the Wagyl created many of the rivers and lakes around Perth. This ancient story helps us understand how important water was to their way of life.

Coastal Whadjuk people have stories passed down through generations about how Rottnest Island became separated from the mainland. Scientists believe this happened between 12,000 and 8,000 years ago, when sea levels rose after the last ice age.

Six Seasons of the Whadjuk Year

Like other Noongar groups, the Whadjuk followed six distinct seasons, moving between the coast and inland areas depending on the weather and food availability. This helped them find the best resources throughout the year.

- Birak (November to December): This was the "fruiting" season, with hot easterly winds. Whadjuk people carefully used controlled fires to manage the land, helping animals for hunting and encouraging new plant growth for food. They harvested wattle seeds to make flour for bread.

- Bunuru (January to February): The "hot-dry" season brought very hot, dry easterly winds, often followed by cooling afternoon sea-breezes (known as the Fremantle doctor). People moved to coastal areas to fish and collect shellfish like abalone.

- Djeran (March to April): This season marked the "first rains and first dew." The weather became cooler with winds from the southwest. Fishing continued, sometimes using special fish traps. They gathered nuts from zamia palms and other seeds. Zamia nuts needed careful preparation to remove natural poisons before eating.

- Makuru (May to June): "The wet" season saw heavy rains. Whadjuk groups moved inland towards the Darling Scarp to hunt animals like grey kangaroos and tammars, as inland water sources refilled.

- Djilba (July to August): This was the "cold-wet" season. People moved to drier areas like Guildford and Canning-Kelmscott. They collected roots and hunted emus, ringtail possums, and kangaroos.

- Kambarang (September to October): "The flowering" season was when wildflowers bloomed everywhere. Rains started to decrease. Families moved back towards the coast, catching frogs, tortoises, and freshwater crayfish like gilgies and blue marron. Birds returning from their long migrations also added to their diet.

These seasons were not fixed by dates but by natural signs, like the call of the motorbike frog or the flowering of specific plants.

Whadjuk Ceremonies and Trade

Whadjuk people used high-quality red ochre in their ceremonies. They got this ochre from a site where Perth Railway Station now stands. They traded this valuable ochre with other groups, even as far away as Uluru. Before European settlement, they used it to color their long hair. They also traded quartz from the Darling Scarp with Balardong groups to make spears.

Early Encounters and Challenges

The Whadjuk people were among the first to experience the arrival of European settlers, as the cities of Perth and Fremantle were built on their traditional lands.

Whadjuk people had likely seen Dutch explorers like Vlamingh and occasional whalers along the coast before Governor James Stirling arrived with settlers. Early meetings, like the one between Captain Irwin and Yellagonga's family near what is now the University of Western Australia, were important first contacts.

As more settlers arrived, they began claiming and fencing off land. This meant Aboriginal people lost access to their traditional hunting grounds and food sources. They did not understand or accept the idea of private land ownership. This led to conflicts, as Aboriginal people sometimes hunted settler's animals or gathered food from gardens, which settlers saw as stealing. These misunderstandings often escalated into violence.

A significant confrontation, sometimes called the "Battle for Perth," occurred when settlers tried to capture Aboriginal people who had gathered at a place called Galup. The Aboriginal people managed to escape. As more land was settled, leaders like Yellagonga had to move their camps, eventually struggling to find food and resources.

The situation was also difficult for Midgegooroo, a Whadjuk leader. His son, Yagan, became a well-known resistance fighter. After a settler was killed, Yagan was arrested. He later escaped and continued to fight for his people's land and rights. Tragically, Yagan was killed by a European boy he knew. His remains were taken to England, but thanks to the efforts of Ken Colbung and others, they were returned to Australia in 1997.

Following a tragic event near Pinjarra, the Whadjuk people faced immense hardship. Many were forced to rely on handouts and settled at places like Mount Eliza. Early efforts by people like Francis Armstrong tried to help, but resources were often limited.

Different governors had different approaches. Governor Stirling used harsh methods, but his replacement, Governor John Hutt, tried to protect Aboriginal rights and offer education. However, many settlers wanted to take Aboriginal lands without fair payment, leading to more conflicts. In 1887, a special area was set aside for the remaining Whadjuk people near Lake Gnangara. This reserve was re-established in 1975.

In 1893, when Western Australia gained self-government, decisions about Aboriginal affairs remained with the British Crown. The state's constitution stated that a small percentage of government money should go to Aboriginal people, but this condition was never fully met.

In 1907, researcher Daisy Bates interviewed some of the last fully initiated Whadjuk Noongar people, including Fanny Balbuk and Joobaitj. They shared important oral traditions about the arrival of Europeans, helping to preserve their history and perspectives.

Whadjuk Social Groups and European Observers

The Whadjuk people were organized into four main groups, each with its own territory, divided by the Swan and Canning Rivers:

- Beeliar: Lived southwest of Perth, between the Canning and Swan Rivers. Midgegooroo was a leader of this group.

- Beeloo: Lived south of the Swan River, extending to the Helena River and Darling Ranges. They moved between the hills in winter and the rivers in spring.

- Mooro: Lived north and west of the Swan River, led by Yellagonga.

- Upper Swan people: Also known as the "mountain people," their specific name is not known today, but early settlers believed Weeip was a leader.

Several Europeans made important efforts to understand Whadjuk Noongar language and culture:

- Robert Menli Lyon befriended Yagan during his exile.

- Francis Armstrong initially tried to build friendships with Aboriginal people.

- George Fletcher Moore quickly learned the Whadjuk dialect and helped in legal matters involving Whadjuk people.

- Lieutenant George Grey also learned the Whadjuk language and was even seen by some Whadjuk as a returned spirit. He later had a distinguished political career.

The Whadjuk people initially called European settlers Djanga, a term for spirits of the dead. This was because the settlers:

- Came from the west, which was the direction of the setting sun and Kuranyup, the land of the dead for the Whadjuk.

- Had pale skin, which was seen as the pallor of people after death.

- Often changed their clothes, making their appearance seem inconsistent.

- Had different smells and sometimes poor dental health, reflecting different hygiene standards of the time.

- Seemed unaffected by diseases that were devastating to Aboriginal people, who had no natural resistance.

The arrival of Europeans brought many new diseases that caused a high number of deaths among Aboriginal people. This was a huge challenge for their communities and traditional ways of understanding health and illness.

Important Aboriginal Camping Sites Around Perth

Many places around Perth hold deep historical and cultural significance for the Whadjuk people:

- Goonininup and Goodinup: These sites, now covered by the Swan Brewery, were important meeting places for trade and ceremonies, especially for red ochre. A sacred birthing stone, the Boya, was moved by settlers, making it difficult for Aboriginal people to continue their traditions there.

- Galup: This was a camping site until the 1920s. When it was closed, Aboriginal groups moved to Jolimont and Innaloo.

- Heirisson Island: The shallow waters here, known as Matagarup (meaning "leg deep"), provided a crossing point for the Swan River. This site was later moved to Burswood.

- Wanneroo: Meaning "the place where women dig yams," this area had many Aboriginal camp sites well into the 20th century.

- Welshpool: A camping site where Daisy Bates conducted many of her interviews with Perth Aboriginal people.

- Bennett Brook: This place is sacred to Aboriginal people, believed to have been formed by the Waugal. It was a traditional camping area with wells for fresh water and fish traps.

- Munday Swamp: Located near Perth Airport, this was an ancient site used for turtle-fishing.

- Bibra Lake: A frequently used camping ground, as shown by many Aboriginal artifacts found there.

- Walyunga: Now a National Park, this is one of the largest known Aboriginal campsites near Perth, used for over 60,000 years.

- Gnangara: Hosted a large Aboriginal camping site and was home to the Aboriginal Community College for many years.

- Allawah Grove: Located near Perth Airport, this was gazetted as an Aboriginal reserve in 1911. After facing harassment and homelessness, many Aboriginal families settled here in the late 1950s, seeking a stable place to live.

- Weld Square: In Northbridge, this was often used as a camping spot, and the Aboriginal Advancement Council established its headquarters there in the 1940s.

Other Whadjuk Names and Spellings

You might see the Whadjuk people referred to by other names or spellings, such as:

- Caractterup tribe

- Derbal

- Ilakuri wongi (language name)

- Juadjuk

- Karakata (a place name for Perth)/Karrakatta (bank of Swan River at Perth)

- Minalnjunga (Yued term meaning 'south man')

- Minnal Yungar

- Wadjuk, Wadjug, Whajook

- Wadjup (a place name for the flats of the Canning River)

- Witja:ri

- Yooadda

- Yooard

A Few Whadjuk Words

Here are a few words from the Whadjuk language:

- gengar (white man)

- mamman (father)

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |