Uluru facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Uluru |

|

|---|---|

| Ayers Rock | |

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 863 m (2,831 ft) |

| Prominence | 348 m (1,142 ft) |

| Geography | |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 550–530 Ma |

| Mountain type | Inselberg |

| Type of rock | Arkose |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park |

| Criteria | v, vi, vii, ix |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

Uluru is a giant sandstone rock formation in the middle of Australia. It is also known as Ayers Rock. It is located in the southern part of the Northern Territory, about 335 kilometers southwest of the town of Alice Springs.

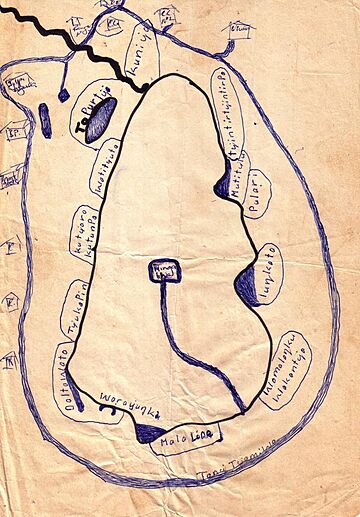

Uluru is a sacred place for the local Aboriginal people, known as the Aṉangu. The area around Uluru has many springs, waterholes, and ancient rock paintings. Because of its importance to both nature and culture, Uluru is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

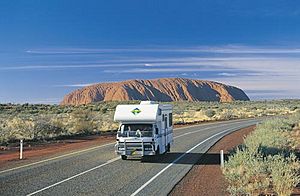

Uluru is one of Australia's most famous natural landmarks. Along with the nearby rock formations of Kata Tjuta, it is part of the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park. It is a popular place for tourists and a very important site for Australia's Indigenous people.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The local Aṉangu people have called this landmark Uluṟu for thousands of years. The word Uluṟu is a proper name and is also used as a family name by some Aṉangu families.

In 1873, a surveyor named William Gosse saw the rock and named it Ayers Rock. He named it after Sir Henry Ayers, who was an important politician in South Australia at the time.

In 1993, a "dual naming" policy was created. This meant that official places could have both their Aboriginal and English names. The rock was first named "Ayers Rock / Uluru." In 2002, the order was changed to Uluru / Ayers Rock to honor the original Aboriginal name.

Description of the Giant Rock

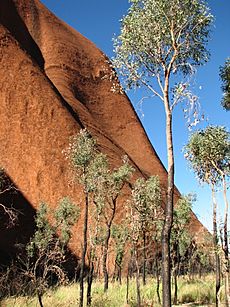

Uluru is a huge sandstone rock that stands 348 meters (1,142 feet) tall. However, most of its size is hidden underground. The total distance around its base is 9.4 kilometers (5.8 miles).

One of the most amazing things about Uluru is how it seems to change color. At sunrise and sunset, it can glow a brilliant red. This red color comes from the iron in the sandstone, which is rusting over time.

About 25 kilometers (16 miles) away from Uluru is another group of large rock domes called Kata Tjuta. Both sites are very important to the Aṉangu people. They lead walking tours to teach visitors about the local plants, animals, and the Dreamtime stories of the land.

History of Uluru

Ancient Times

Scientists have found evidence that people have lived in the area around Uluru for more than 10,000 years.

European Arrival

European explorers first came to this part of Australia in the 1870s. In 1872, an explorer named Ernest Giles saw Kata Tjuta and called it Mount Olga. The next year, William Gosse saw Uluru and named it Ayers Rock.

After the explorers, more settlers arrived. This led to disagreements and difficult times for the Aṉangu people, as they had to compete for resources like food and water.

Becoming a National Park

In the 1920s, the Australian government created reserves where Aboriginal people were encouraged to live. In 1958, the area including Uluru and Kata Tjuta was made into a national park.

Tourism began to grow in the 1950s. Roads were built, and bus tours started bringing visitors to see the rock. In 1964, a chain was installed to help people climb Uluru.

Return to Aṉangu Ownership

On October 26, 1985, the Australian government officially returned the ownership of Uluru to the Aṉangu people. This was a very important event.

As part of the agreement, the Aṉangu leased the land back to the government for 99 years. They decided to manage the park together with Parks Australia. This way, they could protect the land while still allowing visitors to experience its beauty.

Visiting Uluru Today

To protect the environment around Uluru, a special tourist town called Yulara was built outside the national park in the 1970s. Yulara has hotels, campgrounds, and an airport for visitors.

Tourism is important for the area, but it's also a challenge to balance the needs of visitors with protecting the sacred site.

Why Climbing Uluru is Not Allowed

For the Aṉangu people, Uluru is a deeply spiritual place. They believe that the path up the rock is part of a sacred Dreamtime story. For this reason, they have always asked visitors not to climb it. They also felt responsible for the safety of people on the rock, as the climb could be dangerous.

For many years, visitors were allowed to climb, but the Aṉangu continued to share their wishes. Finally, on November 1, 2017, the board of the national park, which includes Aṉangu leaders, voted to close the climb permanently.

The climb was officially closed on October 26, 2019. This date was chosen because it was the 34th anniversary of the day the land was returned to the Aṉangu. The chains that helped climbers were also removed.

Taking Photographs

The Aṉangu ask visitors not to take photos or videos of certain parts of Uluru. These areas are used for special ceremonies and are connected to their spiritual beliefs.

This request helps protect their culture. It prevents Aṉangu from accidentally seeing images of places that are forbidden to them according to their traditions.

Waterfalls on the Rock

Although the area is a desert, it does rain sometimes. When there is heavy rain, amazing waterfalls appear and cascade down the sides of Uluru. This is a rare and beautiful sight.

How Was Uluru Formed?

Geologists call Uluru an inselberg, which means "island mountain." It's a hard rock that has remained while the softer rock around it has worn away over millions of years.

What is Uluru Made Of?

Uluru is made of a type of sandstone called arkose. Arkose is full of a mineral called feldspar. The rock was originally grey, but over millions of years, the iron minerals in the arkose have rusted, giving Uluru its famous reddish-brown color.

Age and Origin

The story of Uluru began about 550 million years ago. At that time, huge mountains, much larger than any we see today, existed in the area.

Rain and rivers washed sand and gravel down from these mountains, creating a huge fan of sediment. Over time, this sand was buried and hardened into the sandstone that forms Uluru.

Later, massive forces within the Earth pushed the layers of rock and tilted them almost vertically. The rock layers of Uluru are now tilted at about 85 degrees. What we see today is just the tip of a huge slab of rock that continues for many kilometers underground.

Dreaming Stories and Traditions

The Aṉangu people believe that ancestral beings created the world and all its features during a time called the Tjukurpa, or the Dreaming. These spirits still live in the land today.

According to the Aṉangu:

The world was once a featureless place. None of the places we know existed until creator beings, in the forms of people, plants and animals, travelled widely across the land. Then, in a process of creation and destruction, they formed the landscape as we know it today. Aṉangu land is still inhabited by the spirits of dozens of these ancestral creator beings...

There are many Dreaming stories about Uluru. One story tells of two tribes of ancestral spirits who were invited to a feast. They were distracted by beautiful Sleepy Lizard Women and never arrived. The angry hosts created a great battle, and the earth rose up in sadness, becoming Uluru.

Another important story is about the Kuniya (woma python) and the Liru (poisonous snake), who fought a great battle at Uluru, creating many of the cracks and scars on the rock.

It is sometimes said that people who take rocks from Uluru will be cursed with bad luck. Many people have mailed rocks back to the park to try to remove the curse.

Plants and Animals

The area around Uluru is home to many unique plants and animals. There are 21 native mammal species, including the mulgara, a small carnivorous marsupial, and the black-flanked rock-wallaby.

The park also has 73 species of reptiles, such as the woma python and the great desert skink. After it rains, four different species of frogs can be found in the waterholes at the base of the rock.

The Aṉangu people have a deep knowledge of the local plants. They use trees like the mulga and centralian bloodwood to make tools like spears and bowls. The red sap from the bloodwood tree is also used as a traditional medicine.

Some plants in the park are very rare. Many of them grow only in the moist areas at the base of Uluru, where water runs off the rock.

Climate and Five Seasons

The park has a hot desert climate. In summer, temperatures can reach over 45°C (113°F). In winter, temperatures can drop below freezing at night.

The Aṉangu people do not follow the four seasons of summer, autumn, winter, and spring. Instead, they recognize five seasons:

- Wanitjunkupai (April/May) – Cooler weather arrives.

- Wari (June/July) – The cold season with morning frost.

- Piriyakutu (August/September/October) – Animals breed and plants flower.

- Mai Wiyaringkupai (November/December) – The hot season when food is harder to find.

- Itjanu (January/February/March) – Stormy season with sudden rain.

| Climate data for Yulara Aero (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1983–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 46.8 (116.2) |

45.8 (114.4) |

45.3 (113.5) |

39.6 (103.3) |

35.7 (96.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

38.7 (101.7) |

42.3 (108.1) |

45.2 (113.4) |

47.1 (116.8) |

47.1 (116.8) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 43.5 (110.3) |

42.4 (108.3) |

40.1 (104.2) |

36.5 (97.7) |

31.4 (88.5) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

36.2 (97.2) |

39.7 (103.5) |

41.8 (107.2) |

43.0 (109.4) |

44.4 (111.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 38.5 (101.3) |

37.2 (99.0) |

34.5 (94.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

24.3 (75.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.9 (84.0) |

32.6 (90.7) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 30.7 (87.3) |

29.7 (85.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

22.2 (72.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.6 (67.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.1 (70.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 17.4 (63.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.7 (58.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 29.5 (1.16) |

34.6 (1.36) |

30.9 (1.22) |

13.9 (0.55) |

13.0 (0.51) |

19.1 (0.75) |

14.7 (0.58) |

4.8 (0.19) |

9.6 (0.38) |

21.7 (0.85) |

33.5 (1.32) |

41.4 (1.63) |

269.0 (10.59) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 3.5 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 28.8 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Uluru (1967–1983) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 45.0 (113.0) |

45.0 (113.0) |

43.5 (110.3) |

38.0 (100.4) |

32.8 (91.0) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.5 (99.5) |

42.0 (107.6) |

44.5 (112.1) |

46.0 (114.8) |

46.0 (114.8) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 43.2 (109.8) |

41.4 (106.5) |

38.6 (101.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.1 (93.4) |

38.4 (101.1) |

40.7 (105.3) |

42.2 (108.0) |

43.9 (111.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 37.5 (99.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

31.4 (88.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

36.8 (98.2) |

29.3 (84.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 29.2 (84.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 20.9 (69.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

12.7 (54.8) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.5 (47.3) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 47.7 (1.88) |

45.8 (1.80) |

49.5 (1.95) |

25.0 (0.98) |

21.6 (0.85) |

21.1 (0.83) |

9.2 (0.36) |

13.2 (0.52) |

18.7 (0.74) |

23.5 (0.93) |

34.5 (1.36) |

18.8 (0.74) |

328.6 (12.94) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 35.3 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology | |||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Uluru para niños

In Spanish: Uluru para niños

- Death of Azaria Chamberlain

- Indigenous Australian art

- List of individual rocks

- List of mountains of the Northern Territory

- Pitjantjatjara § Recognition of sacred sites

- Protected areas of the Northern Territory

- Tietkens expedition of 1889

- Uluru Statement from the Heart

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |