Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National ParkNorthern Territory |

|

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category II (National Park)

|

|

Uluru (close) and Kata Tjuta (far)

|

|

| Nearest town or city | Yulara |

| Established | 23 January 1958 |

| Area | 1,333.72 km2 (515.0 sq mi) |

| Managing authorities |

|

| Website | Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park |

| Footnotes | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Criteria | Cultural: v, vi; Natural: vii, viii |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Extensions | 1994 |

| See also | Protected areas of the Northern Territory |

Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park is a special national park in Australia. It is located in the Northern Territory, about 440 kilometers (273 miles) southwest of Alice Springs. The park is famous for two giant rock formations: Uluṟu (also known as Ayers Rock) and Kata Tjuṯa (also called The Olgas). The park is named after these amazing rocks.

History of Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park

Ancient Stories and Aṉangu Culture

People have lived near Uluṟu for at least 22,000 years. They were hunter-gatherers, meaning they found their food by hunting animals and gathering plants. These people, called the Aṉangu, often moved around to find enough food and water. About 10,000 years ago, they started living in the area all year.

The Aṉangu believe that Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa were created by ancestral spirits. This is part of their creation story, called tjukurpa (the "Dreamtime"). They believe that in the Dreamtime, the world was empty. Then, creator beings traveled across the land. They made all the rocks, rivers, trees, and living things we see today.

The Aṉangu feel that these spirits still live in the land. Each rock formation represents a different ancestral spirit. They connect with these spirits by touching the rocks. This helps them feel blessed or guided. Many spirits, like the kaḻaya (emu) and liru (poisonous snake), are said to travel around the park. Other spirits, like kuniya (a python), stay in one area, like Uluṟu. The great snake king wanambi is believed to live at the top of Kata Tjuṯa.

There are many stories about how Uluṟu was formed. One story says it came from a big battle between ancestral spirits. After many spirits were killed, the earth rose up in sadness, becoming Uluṟu. Another story tells of two serpent spirits, kuniya and liru, who fought many wars there. Their battles left cracks and scars on the rock. Kata Tjuṯa is believed to hold very powerful and secret knowledge. Only initiated men are allowed to know its creation stories. All these stories show that places like Uluṟu are physical proof of what ancestral beings did.

The Aṉangu believe they are directly related to these ancestral beings. They feel their ancestors live within the land. Many places in the park are sacred because of this. The Aṉangu are connected to the land like family. This is because a main idea of tjukurpa is that people and the land are linked. Tjukurpa is passed down through stories, songs, dances, and art. It is their belief system, moral code, and legal code.

Europeans Arrive in the Desert

Europeans first came to the Western Desert of Australia in the 1870s. They were on expeditions, exploring the land. The first European explorer to see Kata Tjuṯa was Ernest Giles in 1872. He named it "Mount Olga" after Queen Olga of Württemberg. He couldn't reach it because a lake blocked his way. The next year, William Gosse reached Uluṟu and named it "Ayers Rock" after Sir Henry Ayers.

More explorers came to find land for raising livestock. But the land was too dry, so they left. The Aṉangu people had little contact with these early explorers. Few white people visited the area after this.

In 1920, the area became an Aboriginal reserve called the Petermann Reserve. It was meant to be a safe place for the Aṉangu. The government hoped they would continue their traditional lifestyle there. In the 1930s, Aṉangu people had more contact with white people. They traded with dingo hunters, getting new foods, tools, and clothes. Many became curious about the white world.

At this time, more land around the reserve was used for livestock. Long droughts caused problems between the Aṉangu and farmers over food and water. Sometimes, meetings with stockmen on nearby cattle stations were violent. In 1934, a man was shot at Uluṟu by police. Aṉangu people became scared and many left the area. Some groups started working on the stations for food. Others moved to towns, wanting the things white people had. Many in the government thought the reserve was not protecting the Aṉangu lifestyle.

Creating the National Park

In the late 1930s, people thought there might be gold in the area. There was a famous story about a lost gold deposit called Lasseter's Reef. In 1940, the Petermann Reserve was made smaller so people could look for gold. At the same time, more people became interested in visiting Uluṟu. A road for vehicles was built in 1948. Tour groups from Alice Springs started arriving a few years later.

In 1958, the government took the area around Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa from the Aṉangu reserve. They created the Ayers Rock–Mt Olga National Park. The government said the rocks were no longer important to the Aṉangu. The new park was managed by the Territory government, which rented the land to tour companies. An airstrip was built near Uluṟu in 1959. Campsites and motels were built in 1967.

The Aṉangu were told not to enter the park, but they still did. Uluṟu was an important stop on their journeys because of the water there. At first, park rangers allowed them to stay. But as more tourists came, there were problems between tourists and Aṉangu. The government tried to move the Aṉangu away by building the Docker River village, 200 km (124 mi) to the west, in 1968.

Because their homeland and lifestyle changed, the Aṉangu had to find new ways to live. They started selling handicrafts and artworks to tourists. Those still living at Uluṟu even opened a store, the Ininti Store, in 1972.

In 1971, Aṉangu groups met with the Office of Aboriginal Affairs. They were worried about how mining and tourism were affecting their land. They also said their sacred sites were not being respected. They asked the government for help.

In 1973, a government report said that Aṉangu should help manage the park. It suggested hiring them as rangers and protecting their sacred sites. It also said that all tourist buildings should be moved out of the park because they were harming the environment. In 1975, the area called Yulara, 15 km (9 mi) to the north, was chosen for this. The airstrip was moved to Yulara in 1982. The resort at Yulara opened in 1983. After that, the campground and motels inside the park were closed, and everything was removed by the end of 1984.

Modern History and Land Ownership

In 1976, the Aboriginal Land Rights Act was passed for the Northern Territory. This law allowed native people to claim ownership of land if they lived on it before Europeans arrived. The Aṉangu asked for ownership of the park's land in 1979. But since it was already a national park, their claim was not allowed. Still, the court decided that the Aṉangu were the "traditional" owners (nguraṟitja) of the land.

There was a long legal case about who truly owned the land. This case continued until November 1983. Then, Prime Minister Bob Hawke agreed that the Aṉangu had rights to Uluṟu. On October 26, 1985, they were given the official ownership papers for the park. The Territory government protested this decision. They had tried hard to stop it. In return for ownership, the Aṉangu agreed to rent the land back to the federal government. This way, it could stay a national park. They started managing the park together in April 1986.

Uluru National Park became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. This meant it was important for its natural beauty. It had already been named a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO in 1977, meaning it was an important natural environment. The park's name changed to Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park in 1993. The next year, it was added to the World Heritage list again, this time as a cultural landscape. This means it is one of the few places in the world important for both its nature and its culture. The listing recognized tjukurpa as the best way to look after the park. In 1995, Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park won a top UNESCO award for setting new ways to manage a World Heritage site.

Geography of the Park

Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park is in the southwest of the Northern Territory, in the middle of Australia. It is about 440 km (273 mi) southwest of Alice Springs. The park covers 1,326 square kilometers (512 sq mi) of flat, red-sand plains. The huge rock formations of Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa are the only big landmarks.

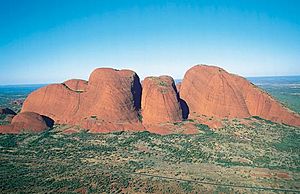

Uluṟu is a sandstone inselberg, which means it's an isolated rock hill. It rises 348 meters (1,142 ft) above the plains. Most of its size is actually hidden underground. Kata Tjuṯa, 25 km (16 mi) west of Uluṟu, is a group of 36 rounded rock domes. These domes are separated by steep valleys. The tallest dome, Mount Olga, is 546 meters (1,791 ft) above the surrounding plain. It is the highest point in the park, at 1,066 meters (3,497 ft) above sea level.

The only permanent village in the park is Muṯitjulu. It is on the eastern side of Uluṟu, and about 350 people live there.

How the Rocks Formed

Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa are made of different types of sedimentary rock. Uluṟu is mostly made of arkose. This is a hard type of sandstone with a lot of feldspar mineral. Kata Tjuṯa is made of conglomerate. This rock has bits of other rocks cemented together by sand and mud.

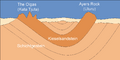

Even though they are different, Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa are thought to be about the same age. They became visible because of folding, faulting, and the erosion of the rock around them.

The park is in a geological area called the Amadeus sedimentary basin. This basin formed about 900 million years ago. Over millions of years, layers of sediment covered it. About 550 million years ago, mountains to the south and west were pushed up. These mountains broke down quickly, and huge pieces of sediment were carried north by rivers. These rivers spread out into at least two fan-shaped deposits. What we see today as Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa are the remains of these ancient deposits.

Around 500 million years ago, a shallow inland sea formed in the basin. Over many years, sand and mud fell to the bottom of the sea. This layer cemented everything together, forming the arkose of Uluṟu and the conglomerate of Kata Tjuṯa. The sea dried up between 400 and 300 million years ago. Then, a long period of folding tilted the horizontal rock layers. The layers of Uluṟu arkose were tilted almost straight up. The conglomerate of Kata Tjuṯa was tilted about 15 to 20 degrees. This means Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa are just the tips of huge rock slabs that go deep underground.

A valley formed between the two rocks about 65 million years ago. Newer layers of sediment were added. These were covered by the red sand we see today, which was brought by wind.

Shaping and Color of the Rocks

The big canyons of Kata Tjuṯa likely formed from faults that appeared when the rock was folding millions of years ago. Many years of weathering made these faults bigger. Water then eroded the rock into the valleys and domes we see today. Uluṟu has deep parallel cracks that run down its sides. These are caused by erosion, mainly from rainwater running off its domed top. The caves around the base of Uluṟu were also formed by water weathering. Erosion of the rock is very slow because its surface is very hard.

The bright orange-red color of the rock surfaces comes from the oxidation (or rusting) of the iron in the arkose. When the arkose is fresh (not exposed to air), it is grey. Uluṟu seems to change color at different times of the day and year. It glows a deep red during sunrise and sunset. The red light in the sky at these times reflects off the rock, sand, and clouds, creating a bright glowing effect.

Water in the Park

Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa is usually arid (dry). Most of the water in the park is underground. This water can stay under the park for thousands of years. Eventually, it all drains through the ground to Lake Amadeus in the north. Knowing where to find this underground water has always been important for people to survive here. It is the only reliable water supply. Both Muṯitjulu and Yulara get their water from ancient underground aquifers. The water has salt, which is removed before use. These aquifers are refilled by rare, heavy rains, usually every ten years or so.

There are no permanent rivers or streams in the park. Creek beds and gullies are mostly found in the valleys around Kata Tjuṯa. These are usually dry, except after heavy rains. However, water can stay under the sand for months. The soils in the park have a lot of clay, which stops water from soaking into the ground too quickly. The only lasting surface water in the park is Muṯitjulu Waterhole (Kapi Muṯitjulu). It is at the base of Uluṟu. It has many waterholes formed by rain running off the rock. These are the only lasting spots of water above ground for hundreds of kilometers. They usually have some water all year.

Climate and Seasons

The park gets about 307.7 millimeters (12 inches) of rain each year. Temperatures can be very hot, reaching 45°C (113°F) in summer. Winter nights can be cold, dropping to -5°C (23°F). On the hottest summer days, UV readings are very high, between 11 and 15.

Even though the Central Australian environment might seem empty, it is a complex ecosystem full of life. Plants and animals have adapted to the extreme conditions. Because of this, the park has some of the most unusual plants and animals on Earth. Many of these have long been important sources of bush tucker (food) and medicine for the local Aboriginal people.

The Aboriginal Australians recognize six seasons:

- Piryakatu (August/September) – Animals breed and food plants flower.

- Wiyaringkupai (October/November) – The really hot season when food becomes scarce.

- Itanju (January/February) – Sudden storms can happen.

- Wanitjunkupai (March) – Cooler weather arrives.

- Tjuntalpa (April/May) – Clouds come from the south.

- Wari (June/July) – Cold season with morning frosts.

Ecology and Wildlife

The park is one of the most important dry land ecosystems in the world. It is one of 15 biosphere reserves in Australia under UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere system. The landscape might look empty, but it is actually a complex ecosystem with many types of life. Plants and animals have adapted to the extreme conditions. As a result, it has some of the most unusual plants and animals on the planet.

Much of the park is made up of flat plains with many kinds of spinifex grasses. There are also large areas of sand dunes, rocky scrubland, and open woodland. The gullies and creek lines that spread out from the rock formations create their own special habitats. This is because water gathers in the ground there.

Park Management

The park is managed jointly by the Aṉangu people and Parks Australia. Parks Australia is the government group that looks after national parks in Australia. The Aṉangu own the land, and they rent it to the government. This rental agreement started in 1985 and lasts for 99 years.

Decisions about the park are made by a Board of Management. The Aṉangu always have more members on this board than anyone else. There are 12 people on the board:

- Eight are from the Aṉangu community.

- One represents the government's tourism department.

- One represents the government's environment department.

- One represents the Northern Territory government.

- The Director of National Parks, who represents Parks Australia.

The Director of National Parks is always on the board. All other members serve for five years, and then new people are chosen. All choices must be approved by the Aṉangu. The staff who work in the park every day are from Parks Australia. A general park manager leads this team and reports to the Director.

Tjukurpa, the Aṉangu legal code, is the main guide for how the park is managed. It explains how to solve problems and what happens if rules are broken. The Aṉangu have used the Australian legal system to protect tjukurpa and their sacred values. Sacred sites are officially registered under Territory law. It is against the law for visitors to enter them. Laws also protect traditional designs from being copied. Aṉangu people have the right to gather food and hunt in the park.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

Mala Walk Uluru

See also

In Spanish: Parque nacional Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa para niños

In Spanish: Parque nacional Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa para niños