Dingo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dingo |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: |

C. l. dingo

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus dingo (Meyer, 1793)

|

|

|

|

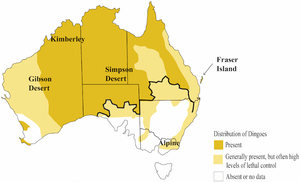

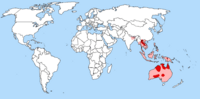

| Dingo range | |

The Dingo (plural: dingoes) is a wild mammal that lives in Australia and parts of South-East Asia. Dingoes look a lot like regular dogs. They arrived in Australia from South-East Asia around 4,000 years ago. You won't find dingoes in Tasmania because the island separated from mainland Australia about 10,000 years ago when sea levels rose. Today, most wild dingoes are not "purebred" anymore; they have mixed with domestic dogs. Their scientific name, Canis lupus dingo, shows they are related to the white-footed wolf found in Asia.

Contents

- What Does a Dingo Look Like?

- How Dingoes Communicate

- Dingo Behavior

- Dingo Reproduction

- Dingoes and Domestic Dogs Mixing

- Dingo Migration

- Dingo Attacks on Humans

- Where Dingoes Live

- Dingoes and Their Impact

- Dingo Legal Status

- How Dingoes Are Controlled

- Protecting Dingoes

- Dingoes as Pets

- Images for kids

- See Also

What Does a Dingo Look Like?

Dingoes are usually about 117 to 124 centimeters (46-49 inches) long, not including their tail. Their tail adds another 30 centimeters (12 inches). They typically weigh between 10 and 20 kilograms (22-44 pounds). Most dingoes have yellow-ginger fur, but some can be tan, black, white, or sandy colored. They usually live for about 14 years.

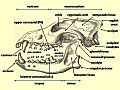

A study in 2014 looked at dingoes from before the 1900s to understand what a "pure" dingo looked like. These dingoes had wider mouths, longer snouts, and flatter skulls compared to domestic dogs. Their fur color could vary a lot, including yellow, white, ginger, and darker shades like tan or black.

A dingo has a wide head, a pointed muzzle, and upright ears. Their eyes can be yellow, orange, or brown. Compared to similar-sized domestic dogs, dingoes have longer muzzles, bigger chewing teeth (called carnassials), longer canine teeth, and flatter skulls. Their tail is somewhat flat and hangs low, not curving over their back.

How Big Are Dingoes?

The average Australian dingo stands about 52 to 60 centimeters (20-24 inches) tall at the shoulders. From nose to tail tip, they measure 117 to 154 centimeters (46-61 inches). Their average weight is 13 to 20 kilograms (29-44 pounds). Some dingoes have been recorded weighing up to 27 to 35 kilograms (60-77 pounds). Male dingoes are usually bigger and heavier than females. Dingoes from northern Australia are generally larger than those from central and southern areas. Their legs are about half the length of their body and head combined.

Dingo Fur Colors

Adult dingoes have short, soft fur that is bushy on their tail. The fur's thickness and length change depending on the climate. Most dingoes are sandy to reddish-brown. They can also have tan patterns, or sometimes be black, light brown, or white. Pure dingoes often have small white markings on their chest, muzzle, tail tip, legs, and paws. Some reddish dingoes might have small, dark stripes on their shoulders.

How Long Do Dingoes Live?

In the wild, dingoes usually live for 3 to 5 years, with a few reaching 7 or 8 years. Some have lived up to 10 years. Dingoes kept in zoos or as pets can live longer, usually between 12 and 14 years.

How Dingoes Communicate

Dingoes communicate using sounds, just like other dogs. However, dingoes howl and whimper more, and bark less, than most domestic dogs. Scientists have found 8 main types of sounds with 19 different variations.

Dingo Barking Sounds

A dingo's bark is short and usually just one sound. They don't bark very often, making up only about 5% of their sounds. Dingo barks are different from wolf barks. Australian dingoes mainly make whooshing noises or a mix of harsh and musical sounds when they bark. They mostly bark to warn others. Sometimes, they combine barks with howls to warn their pups or other pack members. Dingoes also make a "wailing" sound, often near watering holes, to warn other dingoes already there.

Dingo Howling Sounds

Dingoes have three main types of howls: long and steady, rising and falling, and short and sudden. Each type has several variations, but we don't know why they have so many. Howling changes with the seasons and time of day. It's also affected by breeding, moving around, and how stable their social groups are. Dingoes might howl more when food is scarce because they spread out more to find it.

Howling also helps the group stay together. Sometimes, it's a sign of happiness, like when they greet each other. One dingo might start howling, and others will join in, sometimes barking too. In the wild, dingoes howl over long distances to find pack members or to keep other animals away. When many dingoes howl together, their sounds have different pitches. This might help them figure out how many dingoes are in a pack without seeing them.

Other Ways Dingoes Communicate

Dingoes often growl, which makes up about 65% of their sounds. They growl when they are trying to show who is in charge or to defend themselves. They also use scent to mark things like plants, water sources, and hunting grounds. They do this by using their urine, feces, and scent glands. Male dingoes mark more often, especially during mating season. They also "scent-rub" by rolling their neck, shoulders, or back on something that smells like food or other dingoes.

Unlike wolves, dingoes can understand social signals and gestures from humans.

Dingo Behavior

Dingoes are usually active at night in warmer places. In cooler areas, they are active both day and night. Their busiest times are around dusk and dawn. They have short bursts of activity, often less than an hour, with short rests in between. Dingoes move in two ways: searching for food or exploring to find other dingoes.

Generally, dingoes are shy around people. However, some dingoes near human camps, roads, or towns can become less shy. Some experts call all wild dogs in Australia "wild dogs," which includes dingoes and dingo-dog mixes. Other experts see dingoes as domestic dogs that have returned to the wild. Studies in Queensland show that wild dogs can move freely through urban areas at night and seem to get along well.

What Dingoes Eat

Dingoes eat many different things, from insects to large buffalo. Livestock usually makes up only a small part of their diet. Across Australia, 80% of what wild dogs eat comes from 10 main animals: red kangaroo, swamp wallaby, cattle, dusky rat, magpie goose, common brushtail possum, long-haired rat, agile wallaby, European rabbit, and the common wombat. This shows that dingoes are quite specialized hunters. However, in tropical rainforests, they hunt many different mammals. They often prefer medium to large-sized mammals. They have also been known to eat domestic cats.

What dingoes eat changes from place to place. In Queensland's gulf region, they mainly eat feral pigs and agile wallabies. In northern rainforests, they eat magpie geese, rodents, and agile wallabies. In central Australia, they eat rabbits, rodents, lizards, and red kangaroo. On Fraser Island, dingoes eat fish, bandicoots, rodents, echidnas, crabs, small skinks, fruits, plants, and insects.

Dingoes usually drink about one liter of water a day in summer and half a liter in winter. In dry areas during winter, they might get enough water from their prey. Mothers have been seen bringing water back to their pups.

How Dingoes Hunt

Dingoes often kill their prey by biting the throat. They change their hunting methods depending on the situation. For larger animals, two or more dingoes work together because the prey is strong and dangerous. They don't need to hunt in groups for small prey like rabbits.

Kangaroo hunts are more successful in open areas. Dingoes often chase kangaroos towards other pack members who are waiting to cut them off. Young kangaroos are caught more often than adults. Dingoes can also catch birds that don't fly away fast enough. They have even been seen stealing prey from eagles. Three dingoes were once seen working together to kill a large monitor lizard.

Some dingoes live mostly on human food by stealing, scavenging, or begging. This behavior is common in some parts of Australia. It's thought that this might make them lose their natural hunting skills or change their social groups.

Studies have shown that dingoes can quickly learn to hunt and kill sheep, even if they've never seen sheep before. When dingoes attack sheep, they often chase them from behind, causing injuries to the sheep's back legs. Rams are usually attacked from the side to avoid their horns. Dingoes sometimes kill many sheep without eating them all. This might happen because the sheep panic and run, causing the dingo to attack repeatedly.

Dingo attacks on cattle and water buffalo mostly target calves. The success of the hunt depends on how healthy the adult cows are and how well they can protect their calves. Dingoes might try to distract the mother, stir up the herd, or wait for hours to find the weakest animals. They have been seen taking turns biting a buffalo's legs during a chase.

Dingo Social Behavior

Dingoes have flexible social behavior, similar to coyotes or gray wolves. Young male dingoes often live alone and move around a lot. However, adult dingoes that breed often form a stable pack. In areas where dingoes are spread out, breeding pairs might stay together away from other dingoes.

When conditions are good, dingo packs are stable and have their own territory, with little overlap with other packs. The size of a pack often matches the size of the prey available in their territory. In desert areas, dingo groups are smaller and share water sources more freely. The average pack size is usually between 3 and 12 members.

A dingo pack typically includes a male and female pair that mate, their pups from the current year, and sometimes pups from the previous year. There are leaders in the pack, with males usually being more dominant than females. The breeding male is often the leader when the pack travels, eats, or approaches water. Dingoes that are lower in rank will approach a dominant dingo in a slightly crouched position with flat ears and a low tail to keep peace in the pack.

Dingo Reproduction

Dingoes breed once a year. The mating season in Australia is usually between March and May, or sometimes April and June. During this time, dingoes might defend their territories using sounds, growling, and barking.

Most wild female dingoes start breeding when they are two years old. Males become ready to breed between one and three years old. The exact time they start breeding depends on their age, social status, where they live, and the season.

Usually, only the main male and female in a pack (the alpha pair) have pups. Other pack members help raise the pups. The alpha pair actively stops lower-ranking dingoes from breeding. However, if the pack breaks up, lower-ranking or solitary dingoes can successfully breed.

A litter can have 1 to 10 pups, but usually has 5. More males are born than females. The alpha female often kills pups born to other females, which keeps the population from growing too fast. Pups are usually born between May and August (winter), but in tropical areas, they can be born any time of year.

Pups leave their den for the first time at three weeks old and leave completely at eight weeks. Dingo dens in Australia are mostly underground. They can be in old rabbit burrows, rock formations, under large rocks in dry creeks, in hollow logs, or in burrows made by monitor lizards and wombats. Pups usually stay within 3 kilometers (1.8 miles) of the den. Older dingoes go with them on longer trips. Pups start eating solid food when they are 9 to 12 weeks old. Young dingoes become independent at three to six months old, or they leave their family at 10 months when the next mating season begins.

Dingoes and Domestic Dogs Mixing

When Europeans came to Australia, they brought domestic dogs. Some of these dogs escaped or were let go into the wild. These feral dogs then bred with the dingoes. Today, mixes of dingoes and domestic dogs exist in all wild dog groups in Australia. Their numbers have grown so much that there might not be any completely "pure" dingoes left. In some city and country areas, there are large groups made up only of these mixed dogs. In the 1990s, it was thought that about 78% of wild dogs were dingo-hybrids. We don't know the exact number of hybrids today.

Dingo-like domestic dogs and dingo-hybrids can often be told apart from "pure" dingoes by their fur color, as hybrids have more colors and patterns. Hybrids also bark more like domestic dogs. There are also differences in their breeding cycles, skull shapes, and genetics. However, it's hard to be completely sure if a dog is a "pure" dingo because there's no clear definition, and not all features are always reliable.

Scientists have different ideas about this mixing. Many believe that "pure" dingoes should be protected by controlling wild dog populations. They think only "pure" or "nearly pure" dingoes should be saved. A newer idea is that people should accept that dingoes have changed and that it's impossible to bring back the "pure" dingo. This view suggests that conservation should focus on where and how these dogs live, and their role in nature and culture, rather than just their "genetic purity." Both ideas are strongly debated.

Because of this mixing, today's wild dog populations have a wider range of fur colors, skull shapes, and body sizes than before Europeans arrived. Over the last 40 years, the average size of wild dogs has increased by about 20%. It's not clear what would happen if "pure" dingoes disappeared and only hybrids remained. We don't know how this would affect other animals or the Australian environment. However, it's unlikely to cause major problems for the ecosystems.

Dingo Migration

Dingoes usually stay in one area and don't move around much with the seasons. But during times of food shortage, they might travel into farming areas where humans try to control them. In Western Australia in the 1970s, young dingoes were seen traveling long distances. About 10% of young dingoes (under 12 months old) that were caught were later found far from where they were first caught. Males traveled about 21.7 kilometers (13.5 miles) and females about 11 kilometers (6.8 miles). Dingoes traveling into new areas had a lower chance of survival. The longest recorded journey for a dingo with a radio collar was about 250 kilometers (155 miles).

Dingo Attacks on Humans

Even though dingoes are large enough to be dangerous, they usually avoid people. There have been several confirmed dingo attacks, especially on Fraser Island, where tourists often feed them. Most attacks are minor, but some can be serious, and a few have been deadly. Many Australian national parks have signs telling visitors not to feed wildlife. This is because feeding animals is not healthy for them and can encourage unwanted behaviors like snatching food or biting.

Where Dingoes Live

Dingoes live in many different places, including snowy mountain forests, central Australian deserts, and tropical forest wetlands in northern Australia. They are not found in many Australian grasslands, likely because humans have hunted them there. It's hard to find clear differences in dingoes across Australia based on their skulls, size, fur color, or breeding cycles.

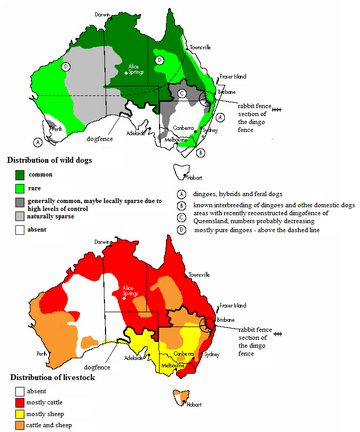

The wild dog population in Australia now includes dingoes and many types of feral domestic dogs (mostly mixed-breeds and dingo-hybrids) with various colors. This population is growing because there is more water, native and introduced prey, livestock, and human food available. Some reports say that wild dogs now hunt in packs in areas where they used to hunt alone. Dingo numbers can be as high as 0.3 per square kilometer in some areas, especially during a rabbit plague.

"Pure" dingoes are common in Northern, North West, and Central Australia. They are rare in Southern and Northeast Australia, and might be gone from Southeastern and Southwestern areas.

Farming caused a big drop in dingo numbers, and they were mostly driven out of sheep farming areas. This was helped by building the Dingo Fence. While dingoes were removed from most areas south of the Dingo Fence, they still live in about 60% of Australia's land, especially in the dry northern areas north of the fence.

In Victoria, wild dogs are mostly found in the thick forests of the Eastern Highlands and in semi-dry areas in the northwest. In New South Wales, they live along the Great Dividing Range and coastal areas, as well as in Sturt National Park.

Across the rest of Australia, dingoes are common, except for the dry eastern half of Western Australia. In parts of South Australia and the Northern Territory, they are naturally scarce. Wild dogs are widespread in the Northern Territory, but rare in the Tanami and Simpson Deserts due to lack of water. However, they gather near man-made water sources there. DNA tests from 2004 suggest that the dingoes on Fraser Island are "pure." A 2013 study showed that dingoes in the Tanami Desert are among the "purest" in Australia.

Dingoes and Their Impact

Dingoes have affected Australia's environment, culture, and economy. Some people believe they caused the extinction of the thylacine on mainland Australia.

Past Extinctions

The dingo is thought to have caused the extinction of the thylacine, the Tasmanian devil, and the Tasmanian nativehen on mainland Australia. This idea comes from the fact that these animals disappeared around the same time dingoes arrived. However, recent studies question this, suggesting that climate change and more humans might have been the cause. Dingoes don't seem to have had the same big impact on the environment as red foxes did later. This might be because of how dingoes hunt and the size of their favorite prey, as well as their lower numbers before Europeans arrived.

The idea that dingoes and thylacines competed for the same food comes from their similar looks. The thylacine had a stronger bite but probably ate smaller prey. The dingo's stronger skull and neck might have allowed it to hunt bigger animals. Dingoes were likely better hunters because they hunted in groups and could defend food better, while thylacines were probably more solitary.

Some argue that the thylacine was a flexible predator that should have survived dingo competition. Instead, it might have been wiped out by humans. This theory doesn't explain how Tasmanian devils and dingoes lived together for so long before devils disappeared from the mainland.

Dingoes and the Environment

Many environmentalists and biologists see the dingo as a natural part of Australian wildlife. This is because dingoes were on the continent before Europeans arrived, and they adapted to the environment.

We don't fully understand the role of wild dogs in Australia's environment, especially in cities. While we know a lot about dingoes in Northern and Central Australia, we know less about wild dogs in the east. Dingoes are thought to have a positive effect on biodiversity where feral foxes are present.

Dingoes are considered apex predators, meaning they are at the top of the food chain. They likely play a key role in controlling the number of prey animals and keeping competition in check. Wild dogs hunt feral livestock like goats and pigs, as well as native animals and introduced animals. The low number of feral goats in Northern Australia might be due to dingoes, but this is still debated.

Studies suggest that dingoes limit how much foxes and cats can access certain resources. If dingoes disappear, there might be more red foxes and feral cats, which would put more pressure on native animals. Where dingo numbers are low, red fox numbers are often high.

It's also possible that dingoes can live with red foxes and feral cats if there's enough food and hiding places. We know very little about the relationship between wild dogs and feral cats, except that they often live in the same areas. Even though wild dogs eat cats, we don't know if this affects cat populations.

The disappearance of dingoes might also lead to an increase in kangaroo, rabbit, and turkey numbers. In areas outside the Dingo Fence, there are fewer dingoes and emus than inside. Since the environment is the same on both sides of the fence, dingoes are thought to control these species. Because of this, some people want to increase dingo numbers or reintroduce them to areas where they are few. This could help protect endangered native species.

Dingoes and the Economy

Wild dogs cause many problems for Australia's livestock industry. They have been seen as pests since Europeans started farming. Sheep are their most common prey, followed by cattle and goats. It's hard to know the exact amount of damage because livestock can die from many causes. Also, if a carcass is found, it's hard to tell if a dingo killed it or just ate from it. Even if livestock isn't a big part of a dingo's diet, they can cause a lot of damage by killing animals without eating them all.

The main problem with dingoes as pests is their attacks on sheep and, to a lesser extent, cattle. It's not just about animals being killed. Harassing sheep can make them use grasslands less well and cause miscarriages.

The cattle industry can handle some wild dogs, so dingoes are not always seen as pests in those areas. But for sheep and goat farmers, any dingo presence is a problem. The biggest threats are dogs living near or inside fenced areas. It's hard to measure sheep losses because of the large grazing lands. Cattle losses vary more and are less documented, but can range from 0-10%, sometimes up to 30%.

Factors like the availability of native prey and how well cattle defend themselves play a big role in losses. A 2003 study in Central Australia found that dingoes had little impact on cattle numbers when there was enough other prey like kangaroos and rabbits. Some cattle owners believe that it's better for a weak mother to lose her calf during a drought so she doesn't have to care for it. These owners are less likely to kill dingoes. The cattle industry might even benefit from dingoes eating rabbits, kangaroos, and rats.

Domestic dogs are the only land predators in Australia big enough to kill adult sheep. Few sheep recover from severe injuries. For lambs, death can have many causes, but predators are often blamed because they eat the carcasses. Attacks by red foxes are rarer than once thought. The sheep and goat industries are more affected by wild dogs than the cattle industry. This is because sheep tend to flock together and panic when scared, and wild dogs are very good at hunting them.

So, the damage to livestock doesn't always match the number of wild dogs in an area. However, a Queensland government report said that wild dogs cost the state about $30 million each year due to livestock losses, disease spread, and control efforts. Livestock losses alone were estimated at $18 million. In Barcaldine, Queensland, up to one-fifth of all sheep are killed by dingoes annually.

Dingoes were also useful to indigenous Australians for hunting, as "living hot water bottles," and as camp dogs. Their scalps were used as money, their teeth for decorations, and their fur for traditional clothes. In some parts of Australia, people pay for dingo fur and scalps. Dingo fur usually isn't worth much, and exporting it is forbidden in states where dingoes are protected. There isn't a big business of catching and killing dingoes just for their fur.

"Pure" dingoes are sometimes important for tourism, attracting visitors. This is especially true on Fraser Island, where dingoes are a symbol used to promote the island. Tourists are drawn to the idea of seeing dingoes up close. Pictures of dingoes are on brochures, websites, and postcards advertising the island.

Dingo Legal Status

Australia has over 500 national parks. The legal status of the dingo changes between different states and territories, and sometimes even within different parts of the same state.

- Australian Government: The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 says that a native species is one that was in Australia before the year 1400. Dingoes are protected in all national parks, reserves, and World Heritage Areas managed by the Australian government.

- Australian Capital Territory: Dingoes are listed as a "pest animal" and require a management plan. However, native animals are protected in national parks, but this protection does not apply to "pest animals."

- New South Wales: Dingoes are considered "wildlife" but are also "unprotected fauna" in some areas. The Wild Dog Destruction Act (1921) applies to the western part of the state and includes dingoes as "wild dogs." Landowners must destroy wild dogs on their property. Owning a dingo or half-bred dingo without a permit can lead to a fine. In other parts of the state, dingoes can be kept as pets.

- Northern Territory: Dingoes are "protected wildlife" because they are native to Australia. A permit is needed for anything involving protected wildlife.

- Queensland: Dingoes are listed as "least concern wildlife," meaning they are protected in National Parks and conservation areas. However, they are also listed as a "pest," requiring landowners to keep their lands free of pests.

- South Australia: Dingoes are considered a protected animal but are also listed as an "unprotected species." The Dog Fence Act 1946 aims to stop wild dogs from entering farming areas south of the dingo-proof fence. Dingoes are listed as "wild dogs" under this act, and landowners must maintain the fence and destroy any wild dog near it.

- Tasmania: Tasmania does not have native dingoes. Dingoes are "restricted animals" and cannot be brought in without a permit. Once in Tasmania, a dingo is considered a dog.

- Victoria: Dingoes are "wildlife" and protected. A permit is needed to keep a dingo, and it must not be mixed with a dog. An order allows dingoes to be trapped, shot, or baited on private land in certain areas to protect livestock, while still protecting them on state-owned land.

- Western Australia: Dingoes are considered "unprotected" native animals. They are also listed as a "declared pest," meaning landowners must take steps to deal with them. The government's policy is to remove dingoes from livestock areas but leave them alone elsewhere.

How Dingoes Are Controlled

Dingo attacks on livestock led to big efforts to keep them away from farms. All states and territories have laws to control dingoes. In the early 1900s, fences were built to keep dingoes away from sheep areas. Some farmers started regularly killing dingoes. Methods for controlling dingoes in sheep areas included hiring "doggers" to reduce dingo numbers using steel traps, baits, firearms, and other methods. Over time, governments also got involved in controlling dingo numbers. All dingoes were seen as a possible danger and were hunted.

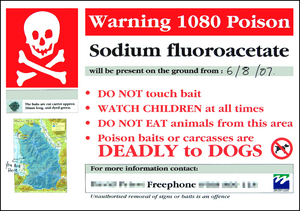

Besides the poison 1080 (used for 40 years), the ways of controlling wild dogs haven't changed much. There's often not enough information about how important dingoes are to indigenous people or how control measures affect other animals. Historically, the needs of indigenous people were not considered when dingoes were controlled. Today, ongoing population control is seen as necessary to reduce the impact of all wild dogs and to help "pure" dingoes survive in the wild.

Keeping Dingoes Away

One method that doesn't work is hanging dead dogs along property borders, thinking it will scare wild dogs away.

Guardian Animals

To protect livestock, people use livestock guardian dogs (like Maremmas), donkeys, alpacas, and llamas.

To keep wild dogs out of certain areas, people try to make those areas unattractive to them, for example, by getting rid of food waste. This forces the dingoes to move somewhere else. Spreading diseases to control them is usually not considered because typical dog diseases are already present, and pets would also get sick.

The Dingo Fence

In the 1920s, the Dingo Fence was built. By 1931, thousands of miles of dingo fences were put up in South Australia. In 1946, these efforts were combined, and the Dingo Fence was completed. It connected with other fences in New South Wales and Queensland. Landowners whose properties border the fence are mainly responsible for maintaining it and get financial help from the government.

Rewards for Killing Dingoes

A reward system for killing dingoes was active from 1846 until the late 1900s. However, despite billions of dollars spent, there's no proof it was an effective control method. So, its importance declined over time.

Poisoning Dingoes

Strychnine is still used in Australia. Baits with the poison 1080 are considered the fastest and safest way to control dogs because dingoes are very sensitive to it. Even small amounts of poison are enough. Aerial baiting (dropping baits from planes) is regulated. Concerns that the tiger quoll might be harmed by the poison led to fewer areas where aerial baiting could be done. In these areas, baits must be placed on the ground.

In recent years, cyanide-ejectors and special collars (filled with 1080) have been tested. The killing of dingoes due to livestock damage decreased in the 1970s as the sheep industry became less important and strychnine use declined. The number of "doggers" also went down, and government-approved aerial baiting increased.

Neutering Dingoes

Owners of dingoes and other domestic dogs are sometimes asked to neuter their pets and keep them supervised. This helps reduce the number of stray dogs and prevents them from mixing with wild dingoes.

How Well Do Control Methods Work?

The effectiveness of control methods is often questioned, as is whether they are worth the cost. The reward system was easily tricked and not useful on a large scale. Animal traps are seen as cruel and not very effective for large areas. Studies suggest that traps mostly catch young dogs that might have died anyway. Also, wild dogs can learn to avoid traps.

Poisonous baits can be very effective if they are made of good meat. However, they don't last long and are sometimes taken by red foxes, quolls, ants, and birds. Aerial baiting can almost wipe out entire dingo populations. Livestock guardian dogs can greatly reduce livestock losses, but they are less effective in large, open areas. Fences are good at keeping wild dogs out of certain areas, but they are expensive to build and need constant upkeep. They also just move the problem somewhere else.

Control measures often lead to smaller dingo packs and break up their social structure. This might actually be bad for the livestock industry because young dingoes take over the empty territories, and then attacks on livestock might increase. However, it's unlikely that control measures could completely get rid of dingoes in Central Australia.

Protecting Dingoes

Until 2004, the dingo was listed as "least concern" on the Red List of Threatened Species. But since then, it has been changed to "vulnerable" because the number of "pure" dingoes has dropped to about 30% due to mixing with domestic dogs.

Dingoes are quite common in many parts of Australia. However, some argue they are endangered because they are interbreeding with other dogs. Dingoes are not a protected species everywhere, but their status varies in different states and territories. They receive different levels of protection in national parks, nature reserves, and other protected areas. In some states, dingoes are considered pests, and landowners are allowed to control them. All other wild dogs in Australia are considered pests.

The dingoes on Fraser Island are very important for conservation. Because they are geographically and genetically isolated, they are considered the most similar to the original dingoes and the "purest" population. These dingoes are not "threatened" by mixing with other domestic dogs. In 2013, two dingo pups were found dead on Fraser Island, sparking outrage. The area manager said there would be serious penalties for anyone who kills or harms Fraser Island dingoes.

In February 2013, a report on Fraser Island dingo management suggested options like ending the intimidation of dingoes, changing tagging practices, regular vet checkups, and creating a permanent dingo sanctuary on the island.

Groups like the Australian Native Dog Conservation Society and the Australian Dingo Conservation Association work to protect "pure" dingoes through breeding programs. However, their efforts are currently seen as ineffective because most of their dogs are not tested or are known to be hybrids.

Dingo conservation mainly focuses on stopping dingoes from breeding with other domestic dogs to save the pure dingo population. This is very difficult and expensive. Conservation efforts are also hard because we don't know how many pure dingoes are left in Australia. Steps to save the pure dingo can only work if we can reliably identify pure dingoes from other domestic dogs. Also, conservation efforts often conflict with control measures.

Protecting pure and healthy dingo populations is more likely to succeed in remote areas where there is little contact with humans and other domestic dogs. In New South Wales, in parks and other non-farming areas, these populations are only controlled if they threaten other native species. Creating "dog-free" buffer zones around areas with pure dingoes is seen as a way to stop mixing. This means all wild dogs outside these conservation areas can be killed. However, studies from 2007 suggest that even strong control in core areas might not stop the mixing process.

We don't currently know what the public thinks about dingo conservation. There is no agreement on what a "pure" dingo is or how much they should be controlled.

Dingoes as Pets

In 1976, the Australian Native Dog Training Society of NSW Ltd. was founded, but it no longer exists. In 1994, the Australian National Kennel Council recognized a dingo breed standard. However, the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (an international dog organization) does not recognize the dingo as a dog breed.

A 2017 study looked at dingoes and older dog breeds to see if they had less desirable traits than newer breeds. The study found that both modern and ancient dog breeds were easier to train than dingoes. They also stared less and were less likely to roll in animal dung. Dingoes' "staring at nothing" behavior might be a reaction to high-frequency sounds that humans and some dogs can't hear. Modern breeds were less afraid of strangers and less likely to escape. Dingo behavior was outside the range of typical dog behaviors, showing that dingoes act like true wild canids and are different from modern domestic dogs. The study concluded that these behaviors might not be good for humans living with dingoes, and they show natural selection rather than human selection. Some people disagree that the dingo should be considered a dog breed, believing that "true" dingoes can be tamed but not truly domesticated.

Dingoes can become very tame if they spend a lot of time with humans. Many indigenous Australians and early European settlers lived with dingoes. Indigenous Australians would take dingo pups from their dens and tame them until they were old enough to leave. Some dingoes were completely tame and acted like other domestic dogs, even helping with herding livestock. Others remained wild and shy. Some dingoes were aggressive and hard to control, but this often depended on how they were raised as pups.

According to Austrian researcher Eberhard Trumler, dingoes are very smart and loving. He suggested that people who want to own dingoes should provide a large, escape-proof enclosure and a partner of the opposite sex. Dingoes can be harder to manage during mating season. They are very attached to their owners and will try to follow them. Dingoes are known for finding any weak spot in a fence or house and escaping to wander through towns. Their intelligence is linked to a great ability to learn and quick understanding. Dingoes are thought to not handle pressure well, but this goes against their history as working dogs. They are good as shepherd dogs because keeping a group together is natural for them. Some dingoes are still used as shepherd dogs today. Dingoes also have strong instincts for cleanliness and can be easily housebroken.

Images for kids

-

Dingo on the beach at Fraser Island, Queensland

-

Portrait of a Large Dog from New Holland by George Stubbs, 1772. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

-

"Dog of New South Wales" illustrated in The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay in 1788

-

The Sahul Shelf and the Sunda Shelf during the past 12,000 years: Tasmania separated from the mainland 12,000 YBP, and New Guinea separated from the mainland 6,500–8,500 YBP.

See Also

In Spanish: Dingo para niños

In Spanish: Dingo para niños