Sodium fluoroacetate facts for kids

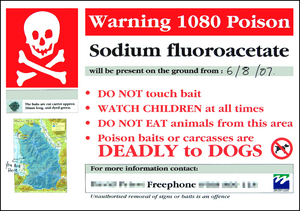

Sodium fluoroacetate, also known as compound 1080, is a chemical compound that contains fluorine. It is a colorless salt that tastes a bit like regular table salt. This substance is mainly used as a rodenticide, which means it helps control rodents like rats and mice.

Contents

What is Sodium Fluoroacetate?

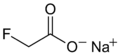

Sodium fluoroacetate is a chemical with the formula FCH2CO2Na. It looks like a fluffy, white powder and doesn't have any smell. It can dissolve easily in water.

History of Compound 1080

Scientists first reported that sodium fluoroacetate was good at controlling rodents in 1942. The name "1080" comes from its catalog number, which then became its common name.

Where is it Found Naturally?

Fluoroacetate is actually found naturally in at least 40 different types of plants! These plants grow in places like Australia, Brazil, and Africa. It's one of only a few natural products that contain fluorine.

Poison Plants in Australia

One group of plants that contain fluoroacetate is called Gastrolobium. These are flowering plants, and most of them grow in southwestern Western Australia. People there call them "poison peas."

These "poison peas" take in fluoroacetate from the soil. Some native Australian animals, like brush-tailed possums, bush rats, and western grey kangaroos, have developed a way to safely eat these plants. However, farm animals and other animals brought to Australia from different places (like red foxes) are very sensitive to the poison. This natural poison has even helped protect some native animals by making it harder for non-native predators, like cats, to survive in areas where these plants grow.

Farmers in Western Australia sometimes have to remove the top layer of soil that contains these poison pea seeds before they can plant crops. Also, after bushfires in north-western Queensland, cattle farmers have to move their livestock away before the poisonous Gastrolobium grandiflorum plants grow back.

Another plant, Dichapetalum cymosum (known as gifblaar or poison leaf), was found to contain a similar compound called potassium fluoroacetate in 1944. Long ago, people in Sierra Leone used extracts from a plant called Chailletia toxicaria to poison rats. Several native Australian plants also contain this toxin, including Gompholobium, Oxylobium, Nemcia, and Acacia. Even New Zealand's native Puha plant has very small amounts of 1080.

How it Affects Animals

Sodium fluoroacetate is toxic to all animals that need oxygen to live, and it's especially harmful to mammals and insects. For humans, eating just a small amount (2–10 milligrams per kilogram of body weight) can be deadly.

Different animals react differently to the poison. Dogs, cats, and pigs are some of the most sensitive animals.

Scientists have found a special enzyme in a soil bacterium that can break down fluoroacetate, making it harmless.

How the Poison Works

Fluoroacetate is very similar in structure to a natural chemical called acetate, which is super important for how cells get energy. Because they are so similar, fluoroacetate tricks the body.

When an animal eats fluoroacetate, its body changes it into another chemical called 2-fluorocitrate. This 2-fluorocitrate then blocks a key process in the body called the citric acid cycle. This cycle is how cells make energy from food. When it's blocked, cells can't get the energy they need, especially in important organs like the brain and heart.

Signs of Poisoning

In humans, signs of poisoning usually show up between 30 minutes and three hours after exposure. At first, people might feel sick to their stomach, throw up, or have stomach pain. They might also sweat, feel confused, or become agitated.

If the poisoning is serious, it can affect the heart, causing it to beat too fast or too slow, or cause low blood pressure. It can also affect the brain, leading to muscle twitches, seizures, and eventually a loss of consciousness. Death usually happens because of heart problems or severe low blood pressure.

For pets, the signs can be different. Dogs often show nervous system problems like seizures, making noises, and running around without control. Larger animals like cattle and sheep mostly show heart problems.

Even small amounts of the poison can damage organs that need a lot of energy, such as the brain, heart, lungs, and a fetus (unborn baby). If the dose is not deadly, the body usually breaks down and gets rid of the poison within four days.

Treatment for Poisoning

There isn't a specific cure for sodium fluoroacetate poisoning. Doctors and veterinarians focus on supporting the animal or person to help their body cope. This might involve giving muscle relaxants, medicines to stop seizures, or using machines to help with breathing.

Some research on monkeys has shown that a substance called glyceryl monoacetate might help if given soon after the poison is eaten. This substance might give the cells the acetate they need to keep making energy. However, few animals or people have fully recovered after eating a lot of sodium fluoroacetate.

In one study, scientists used genetic engineering to make bacteria in sheep's stomachs produce the enzyme that breaks down fluoroacetate. Sheep given these bacteria showed fewer signs of poisoning after eating sodium fluoroacetate.

Using it as a Pesticide

Sodium fluoroacetate is used as a pesticide to control harmful mammals. Farmers use it to protect their crops and pastures from animals that eat plants. In New Zealand and Australia, it's also used to control non-native animals that harm native wildlife and plants.

In Australia

Australia started using sodium fluoroacetate to control rabbits in the early 1950s. It's considered very effective and safe there. It's an important part of programs to control rabbits, foxes, wild dogs, and feral pigs.

Since 1994, using 1080 baits to control foxes in Western Australia has helped increase the numbers of several native animal species. For the first time, three mammal species were even removed from the state's endangered species list. In Australia, some deaths of native animals from 1080 baits are considered acceptable because the introduced animals cause much more harm by eating native plants and preying on native animals.

The Western Shield project in Western Australia drops 1080-baited meat from the air to kill predators like wild dogs and foxes. Cats are harder to control this way because they usually don't eat scavenged meat. Some native Australian animals, like a certain type of tammar wallaby, have developed a partial immunity to fluoroacetate. This means using 1080 can reduce harm to these specific native animals.

In 2011, over 3,750 toxic baits with 1080 were spread across a large area in Tasmania to try and get rid of red foxes. The baits were buried to protect native animals like Tasmanian devils. However, native animals are also sometimes targeted. In 2005, up to 200,000 Bennett's wallabies on King Island were intentionally poisoned with 1080.

In 2016, a new poison called PAPP became available. Some groups, like the RSPCA, prefer PAPP because it kills faster, causes less suffering, and has an antidote. However, 1080 is still used to try and reduce feral cat populations.

In New Zealand

New Zealand uses more sodium fluoroacetate than any other country. This is because New Zealand has very few native land mammals (only two types of bats), and many introduced animals have caused a lot of damage to the native plants and wildlife.

1080 is used in New Zealand to control possums, rats, stoats, deer, and rabbits. The main groups using it are OSPRI New Zealand and the Department of Conservation, even though some people strongly oppose its use.

In the United States

In the United States, sodium fluoroacetate is used to kill coyotes. Before 1972, it was used more widely as a cheap poison for predators and rodents. Now, its use is restricted, mainly for "toxic collars" worn by livestock to kill coyotes that attack them.

Other Countries

1080 is also used as a rodenticide in Mexico, Japan, Korea, and Israel. For example, in Israel, it's used to protect crops from rodents like field mice.

Effects on the Environment

Water

Because 1080 dissolves easily in water, rain, streams, and groundwater can spread and dilute it. When it's in natural water with living things like aquatic plants or tiny organisms, it breaks down into harmless substances.

Studies have shown that it's possible, but not common, for waterways to become significantly contaminated after 1080 baits are spread from the air. Research in New Zealand found that 1080 placed in small streams disappeared from the placement site within 8 hours as it washed downstream.

In New Zealand, water is regularly checked after 1080 is dropped from the air. Out of over 2,400 water samples tested between 1990 and 2010, almost all (96.5%) had no detectable 1080. Only six samples had levels equal to or above the safe drinking water limit, and none of these were from actual drinking water supplies.

Soil

Sodium fluoroacetate dissolves in water, so any leftover poison from baits soaks into the soil. Once in the soil, tiny living things like bacteria and fungi break it down into harmless substances.

Birds

Sometimes, if not done carefully, aerial 1080 operations can affect local bird populations. In New Zealand, some native and introduced birds have been found dead after 1080 drops. Most of these deaths happened in the 1970s when poor-quality baits were used.

However, many native New Zealand bird populations have actually benefited from 1080 operations because it reduces the number of predators. Birds like Kokako, blue duck, kiwi, and kaka have shown increased survival rates for chicks and adults, leading to larger populations.

On the other hand, some kea (a native alpine parrot) have been killed during possum control operations. Kea are known to be curious and omnivorous, which makes them more likely to eat poison baits. Research suggests that kea living near people are more likely to eat poison because they are used to scavenging human food.

Reptiles and Amphibians

Reptiles and amphibians can be affected by 1080, but they are much less sensitive to it than mammals. Studies in Australia show that lizards are generally more tolerant to 1080. Even if lizards ate only poisoned insects, they probably wouldn't get a deadly dose.

In New Zealand, studies suggest that native frogs like Archey's frog and Hochstetter's frog could absorb 1080 from contaminated water, soil, or prey. However, many factors in the wild make this less likely. Also, killing feral cats and stoats (which eat native skinks and geckos) with 1080 can actually help native skink and gecko populations recover.

Fish

Fish are generally not very sensitive to 1080. Tests in the US showed that 1080 is "practically non-toxic" to fish like bluegill sunfish and rainbow trout, even at high concentrations. The levels of 1080 found in water after aerial operations are far too low to harm freshwater fish.

Invertebrates

Insects can be poisoned by 1080. Some studies in New Zealand showed that insect numbers might temporarily drop near toxic baits, but they usually return to normal levels within a few days after the bait is removed. Other studies found no negative effects on insect communities.

There's also evidence that 1080 operations can benefit invertebrate species in New Zealand. Possums and rats are a serious threat to native insects and spiders, which evolved without mammal predators. For example, one possum can eat up to 60 endangered native land snails in a single night.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Fluoroacetato de sodio para niños

In Spanish: Fluoroacetato de sodio para niños

- Fluoroacetamide

- Methyl fluoroacetate

- Fluoroethyl fluoroacetate

- Fluoroaspirin

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |