Thylacine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Thylacine |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: |

†T. cynocephalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Thylacinus cynocephalus (Harris, 1808)

|

|

The thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), also known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, was a meat-eating marsupial. This means it was a mammal that carried its young in a pouch. It used to live in Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea.

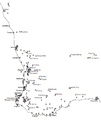

Thylacines died out in New Guinea and mainland Australia about 3,600 to 3,200 years ago. This might have happened because of the dingo, which arrived around the same time. The first detailed scientific description of the thylacine was made in 1808 by George Prideaux Robert Harris. He was Tasmania's Deputy Surveyor-General.

The name "thylacine" comes from a Greek word meaning "pouch" or "sack". This refers to the pouch where the female carried her babies. The thylacine has become an important symbol of Tasmania. You can even see it on the official coat of arms of Tasmania.

Contents

Why the Thylacine Disappeared

Thylacines were once common all over Australia. Scientists have found their fossils in Queensland. There are also ancient paintings of them in Western Australia. A preserved body was even found in a cave in South Australia. This body was about 4,650 years old.

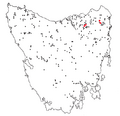

The thylacine started to disappear from mainland Australia about 5,000 years ago. This was around the same time that dingos arrived in Australia. About 10,000 years ago, rising sea levels separated Tasmania from the mainland. This created the Bass Strait, which dingoes never crossed. So, when Europeans first arrived in Australia in 1788, thylacines were only living in Tasmania.

French explorers first saw a thylacine on May 13, 1792. This was written down by the naturalist Jacques Labillardière. Later, in 1808, George Prideaux Robert Harris wrote the first detailed scientific description.

Farmers believed thylacines were killing their sheep. Because of this, people hunted them. The Tasmanian government even paid farmers for each thylacine they killed. The last known thylacine was shot on May 13, 1930, by a farmer named Wilfred Batty in Mawbanna, Tasmania. The government made laws to protect them just a few months before the last one died. Thylacines are now extinct, meaning there are none left alive anywhere in the world.

What Did the Thylacine Look Like?

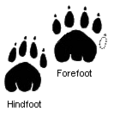

The thylacine was about 1.8 meters (71 inches) long. Its tail could be up to 53 centimeters (21 inches) long. It stood about 58 centimeters (23 inches) tall and could weigh up to 30 kilograms (66 pounds). Its fur was grey and brown with 16 black or brown stripes on its back.

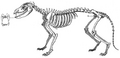

It looked a bit like a dog, but its back, rump, and tail were more like a kangaroo. Its tail was quite stiff, and its legs were short. It had teeth similar to a dog's, but with more incisor teeth. The thylacine could open its mouth very wide, about 120 degrees. Only snakes can open their jaws as widely. Female thylacines had a crescent-shaped pouch that opened towards the back. They used this pouch to carry their young.

Thylacines were nocturnal hunters, meaning they hunted at night. They ate animals like wallabies, rats, birds, echidnas, rabbits, and sheep. As marsupials, female thylacines carried their babies in a pouch.

Modern Research and De-extinction Efforts

Scientists are very interested in the thylacine. In 1999, the Australian Museum in Sydney started a project to try and clone the animal. The team wanted to use genetic material from preserved thylacine specimens. Their goal was to bring the species back from extinction. Some scientists thought this project was just for public attention.

In late 2002, the researchers had some success. They were able to get usable DNA from the old specimens. However, in 2005, the museum announced they were stopping the project. Tests showed the DNA was not good enough for cloning. Later that year, the project was restarted by a group of universities and a research institute.

In 2008, researchers from the University of Melbourne and the University of Texas at Austin made an important discovery. They managed to make a thylacine gene work in transgenic mice. This gene was taken from 100-year-old thylacine tissues. Their findings were published in a science journal in 2009.

In August 2022, the University of Melbourne announced a new partnership. They are working with a company called Colossal Biosciences. They plan to try and re-create the thylacine using its closest living relative, the fat-tailed dunnart. The university has already sequenced the full genetic code of a young thylacine. They are also setting up a special lab for this project. Their hope is to eventually bring the thylacine back to Tasmania.

Images for kids

-

Skeleton in Cambridge University Museum of Zoology, England

-

The skulls of the thylacine (left) and the timber wolf, Canis lupus, are quite similar, although the species are only distantly related. Studies show the skull shape of the red fox, Vulpes vulpes, is even closer to that of the thylacine.

-

Thylacine rock art at Ubirr

-

One of only two known photos of a thylacine with a distended pouch, bearing young. Adelaide Zoo, 1889

-

Thylacine family at Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, 1909

-

This 1921 photo by Henry Burrell of a thylacine with a chicken was widely distributed and may have helped secure the animal's reputation as a poultry thief. In fact the image is cropped to hide the fenced run and housing, and analysis by one researcher has concluded that this thylacine is a mounted specimen, posed for the camera.

-

Thylacine skeleton, Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris

-

John Gould's lithographic plate from "Mammals of Australia"

See also

Template:Kids robot.svg In Spanish: Tilacino para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |