Yagan facts for kids

Yagan (born around 1795 – died 11 July 1833) was a brave Aboriginal Australian warrior. He belonged to the Noongar people, who are the traditional owners of the land around what is now Perth.

Yagan became a legendary figure because he fought for his people's rights. He was wanted by the authorities after he killed a farmer's servant. This was an act of retaliation (getting back at someone for something they did). Another servant had shot and killed a Noongar person who was taking potatoes and chickens. The government offered a bounty (a reward) for Yagan's capture, dead or alive. A young settler named William Keates shot and killed him.

After Yagan was killed, settlers cut off his head to claim the reward. His head was sent to London and shown in a museum. It was kept there for over 100 years before being buried in an unmarked grave in 1964. For many years, the Noongar people asked for Yagan's head to be returned to Australia. This was important for their beliefs and because Yagan was a respected leader.

His burial site was found in 1993. Four years later, his head was dug up and brought back to Australia. After much discussion among the Noongar community about where to bury it, Yagan's head was finally laid to rest in a traditional ceremony in the Swan Valley in July 2010. This was 177 years after his death.

Yagan's Life Story

Growing Up

Yagan was part of the Whadjuk Noongar people. He belonged to a family group called the Beeliar. This group lived on the land south of the Swan and Canning rivers. They also used a much larger area for hunting and gathering food. This area stretched north to Lake Monger and northeast to the Helena River. The Beeliar people could move freely across their neighbours' lands, perhaps because they were related through family and marriage.

Yagan was born around 1795. His father, Midgegooroo, was an important elder (leader) of the Beeliar people. Yagan was likely a respected member of his community.

His Appearance

Historians believe Yagan had a wife and two children, though some records say he was unmarried. He was described as taller than average and very strong. Yagan had a special tribal tattoo on his right shoulder. This tattoo showed he was a man of high standing in his community's laws. People said he was the strongest in his tribe. He was known for being able to throw a spear very far and accurately.

Meeting the Settlers

Yagan was about 35 years old in 1829 when British settlers arrived. They started the Swan River Colony in his homeland. For the first two years, relations between the settlers and Noongar people were mostly friendly. There wasn't much competition for food or land. The Noongar people even welcomed the white settlers, believing they were the spirits of their ancestors returning. They sometimes shared fish.

But over time, problems grew. The settlers thought the Noongar people were nomads (people who move around without a fixed home) and didn't own the land. The colonists started fencing off land for farms. This meant the Noongar people could no longer reach their traditional hunting grounds and sacred places.

To find food, the Noongar people began taking crops and cattle from the settlers. They also liked the settlers' flour and other supplies. This became a big problem for the colony. Also, the Noongar practice of firestick farming (lighting fires to help plants grow and hunt animals) sometimes threatened the settlers' homes and crops.

Conflicts Begin

In December 1831, Yagan and his father led the first major Aboriginal resistance against the white settlers. A servant named Thomas Smedley shot and killed one of Yagan's family members who was taking potatoes. A few days later, Yagan, Midgegooroo, and others went to the farmhouse. They broke through the walls and killed Erin Entwhistle, another servant.

Under Noongar tribal law, a killing had to be avenged by killing someone from the murderer's group. The Noongar people saw the servants as part of the settlers' group. The settlers, however, saw this as an unprovoked murder. They sent a group to arrest Yagan's group, but they couldn't find them.

In June 1832, Yagan led an attack on two workers near the Canning River. One worker, William Gaze, was wounded and later died. The government declared Yagan an outlaw and offered a £20 reward for his capture.

Yagan was finally captured in October 1832 by fishermen. He was taken to the Round House prison in Fremantle. Yagan was sentenced to death. However, a settler named Robert Menli Lyon argued that Yagan was defending his land. Lyon said Yagan should be treated as a prisoner of war, not a criminal. Yagan and his men were sent to Carnac Island under Lyon's supervision.

Lyon hoped to teach Yagan British ways and get him to cooperate. He spent many hours learning Yagan's language and customs. After a month, Yagan and his companions escaped by stealing a boat and rowing back to the mainland. The government did not chase them, thinking they had been punished enough.

Meeting Other Tribes

In January 1833, two Noongar men, Gyallipert and Manyat, visited Perth from King George Sound. Relations between settlers and natives were friendly there. Settlers arranged for them to meet local Noongar people to encourage peace. On January 26, Yagan led ten armed Noongar men to meet the visitors near Lake Monger. They exchanged weapons and held a corroboree (a traditional Aboriginal dance and gathering). Yagan and Gyallipert showed off their spear-throwing skills. Yagan hit a walking stick from 25 metres away!

In March, Yagan got permission to hold another corroboree in Perth. The Perth Gazette newspaper wrote that Yagan "was master of ceremonies and acquitted himself with infinite grace and dignity."

Despite these friendly meetings, Yagan was involved in more small conflicts with settlers. He sometimes demanded food or guns. The Perth Gazette called him a "desperado" who was "at the head and front of any mischief."

Hunted Down

On April 29, Yagan's brother, Domjum, was badly injured while stealing flour from a store and died in jail. Yagan reportedly swore revenge. Between 50 and 60 Noongar people gathered and ambushed a group of settlers, killing two men, Tom and John Velvick. Some historians think the Velvicks were targeted because they had hurt Aboriginal people before.

After the Velvicks were killed, the Lieutenant-Governor Frederick Irwin declared Yagan, Midgegooroo, and Munday outlaws. He offered rewards: £20 for Midgegooroo and Munday, and £30 for Yagan, dead or alive. Midgegooroo was captured and executed by a firing squad on May 17. Yagan remained free for over two months.

Late in May, George Fletcher Moore saw Yagan on his land and spoke with him. Yagan asked if Midgegooroo was dead. Moore didn't answer, but a servant said Midgegooroo was a prisoner. Yagan warned, "White man shoot Midgegooroo, Yagan kill three." Moore didn't try to stop Yagan, writing that everyone wanted him caught, but no one wanted to be the one to catch him.

His Death

On July 11, 1833, two teenage brothers, William and James Keates, were herding cattle near Guildford. A group of Noongar people, including Yagan, approached them. The Keates brothers suggested Yagan stay with them to avoid being arrested. While Yagan was with them, the brothers decided to kill him for the reward.

William Keates shot Yagan. James shot Heegan, another Noongar man, who was throwing his spear. The brothers ran away. Other Noongar people caught William and speared him to death. James escaped by swimming across the river. He soon returned with armed settlers from a nearby estate.

When the settlers arrived, Yagan was dead, and Heegan was dying. The settlers cut off Yagan's head and skinned his back to keep his tribal markings as a trophy. They buried the bodies nearby.

James Keates claimed the reward, but many people criticized his actions. The Perth Gazette called Yagan's killing "a wild and treacherous act." Keates left the colony the next month, possibly fearing revenge.

Yagan's Head

Display and Burial in England

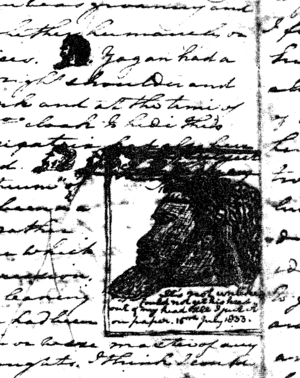

Yagan's head was first taken to Henry Bull's house. George Fletcher Moore saw it there and drew it in his diary, hoping it might end up in a museum. The head was preserved by smoking it.

In September 1833, Governor Irwin sailed to London, partly to explain the events leading to Yagan's death. Ensign Robert Dale also travelled with him, having somehow gotten Yagan's head. Dale tried to sell the head to scientists in London. He eventually made an agreement with Thomas Pettigrew, a surgeon who was famous for showing off ancient Egyptian mummies at parties. Pettigrew displayed Yagan's head on a table with a painting of King George Sound. The head was decorated with a headband and feathers.

Pettigrew had a phrenologist (someone who studied the shape of skulls) examine the head. The phrenologist's findings matched what Europeans at the time thought about Aboriginal Australians. Dale published these findings in a pamphlet.

In October 1835, Yagan's head was given to the Liverpool Royal Institution. In 1894, it was moved to the Liverpool Museum. By the 1960s, Yagan's head was in poor condition. In April 1964, the museum decided to bury it. On April 10, 1964, Yagan's head was buried in Everton Cemetery in Liverpool, along with a Peruvian mummy and a Māori head. Later, 20 stillborn babies and two infants were buried directly over the box containing Yagan's head.

Efforts to Bring it Home

Starting in the early 1980s, many Noongar groups wanted Yagan's head returned to Australia. There was no clear record of where the head was after Pettigrew had it. Aboriginal leader Ken Colbung was asked to find it. In the early 1990s, he got help from archaeologist Peter Ucko. One of Ucko's researchers, Cressida Fforde, found the head in December 1993.

Colbung then applied to dig up the remains. However, rules required permission from the families of the 22 infants buried above Yagan's head. Colbung's lawyers asked for this rule to be waived, saying the exhumation was very important to Yagan's relatives and to Australia.

Divisions began to appear within the Noongar community in Perth. Some elders questioned Colbung's role. However, at a public meeting in Perth on July 25, everyone agreed to work together. A Yagan Steering Committee was formed to manage the return of the head.

In January 1995, the Home Office said it couldn't waive the rule about getting consent from the infants' families. Only one family gave unconditional consent. So, in June 1995, the request to dig up the head was rejected.

The Yagan Steering Committee decided to ask Australian and British politicians for help. In 1997, Colbung was invited to the UK. His visit got a lot of media attention and put more pressure on the British Government. He even got support from the Prime Minister of Australia, John Howard.

Digging Up the Head

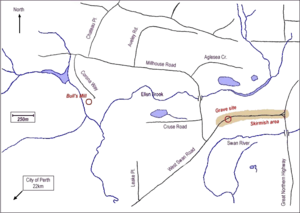

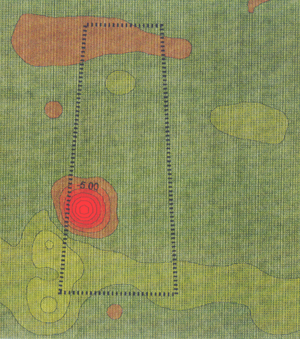

While Colbung was in the UK, experts used special equipment like electromagnetic and ground penetrating radar to survey the grave site. They found the likely spot of the box and figured out it could be reached from the side without disturbing other remains. This information was given to the Home Office, leading to more talks between the British and Australian governments.

The Home Office was concerned about letters they received objecting to Colbung's involvement. Colbung asked his elders to confirm he was the right person to apply. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) held a meeting in Perth, where it was again agreed that Colbung's application should go forward.

Colbung kept pushing for the head to be dug up before July 11, the anniversary of Yagan's death. But his request wasn't met. He returned to Australia without the head on July 15.

The exhumation of Yagan's head finally happened without Colbung knowing. Workers dug down 6 feet next to the grave and then tunnelled horizontally to the box. This way, no other remains were disturbed. The next day, a forensic palaeontologist from the University of Bradford confirmed it was Yagan's skull by matching the fractures to old descriptions. The skull was kept at the museum until August 29, when it was given to the Liverpool City Council.

Bringing it Home

On August 27, 1997, a group of Noongar people, including Ken Colbung, arrived in the UK to collect Yagan's head. The handover was delayed when a Noongar man named Corrie Bodney tried to stop it in court. He claimed his family had sole responsibility for Yagan's remains. On August 29, Justice Henry Wallwork rejected the request, as Bodney had agreed to the plans before.

Yagan's skull was given to the Noongar group at a ceremony in Liverpool Town Hall on August 31, 1997. Colbung's comments at the ceremony caused a stir in Australia, with many people expressing shock. Colbung later said his comments were misunderstood.

Some international media treated the story as a joke. For example, U.S. News & World Report called Yagan's head a "pickled curio."

Getting Ready for Reburial

When Yagan's head returned to Perth, it continued to cause discussion. A committee was formed to rebury the head, led by Richard Wilkes. The reburial was delayed by disagreements among elders about where to bury it. This was mainly because no one was sure where the rest of his body was.

Attempts were made to find Yagan's body, believed to be in Belhus. Surveys in 1998 and 2000 didn't find any remains. Disputes then arose about whether the head could be buried separately from the body. Wilkes said it could, as long as it was placed where Yagan was killed. This way, Dreamtime spirits could reunite the remains.

In 1998, a plan called Yagan's Gravesite Master Plan was published. It discussed how to manage the land where Yagan's remains were thought to be. There was talk of turning the site into an Indigenous burial ground.

Yagan's head was kept in a bank vault for a while. Then, forensics experts made a model from it. After that, it was stored at Western Australia's state mortuary. Plans to rebury the head were put off many times, causing ongoing conflict among Noongar groups. In September 2008, it was reported that Yagan's head would be reburied in November, and a Yagan Memorial Park would be built. But the reburial was moved to July 2009 due to planning issues. In March 2009, it was announced that the Department of Indigenous Affairs gave the City of Swan over A$500,000 to develop the park.

Reburial Ceremony

Yagan's head was finally buried in a private ceremony on July 10, 2010. Only invited Noongar elders attended. The site in Belhus was chosen because it is believed to be near where the rest of Yagan's body was buried.

The burial happened at the same time as a ceremony to open the Yagan Memorial Park. About 300 people attended, including Noongar elders and government officials. Premier Colin Barnett called it "a wonderful day for all West Australians."

The artworks for the Yagan Memorial Park were designed by Peter Farmer, Sandra Hill, Jenny Dawson, and Kylie Ricks. Dawson and Hill created an entry wall telling Yagan's story. Farmer designed the park entry statements, and Ricks designed the female coolamon (a traditional Aboriginal carrying dish).

Yagan's Importance Today

Yagan was not a cruel killer, as some settlers thought. He tried to use the Noongar system of justice to resolve conflicts between his people and the colonists. Bringing Yagan's head back made him even more famous. He is now seen as an important historical figure across Australia. Information about him is taught in Western Australian schools.

He is most important to the Noongar people, who see him as "a revered, cherished and heroic individual." They consider him a patriot and a visionary hero of Western Australia's South-West. The return of his head was compared by some Indigenous Australians to the return of Australia's unknown soldier from Gallipoli in 1993.

The former Upper Swan Bridge, which carries the Great Northern Highway over the Swan River, was renamed the Yagan Bridge in 2010.

A public plaza in the Perth central business district was named Yagan Square. It features a 9-metre-tall statue called "Wirin." The plaza opened on March 3, 2018.

See also

In Spanish: Yagan para niños

In Spanish: Yagan para niños

- Jandamarra, a Bunuba warrior.

- Musquito, a warrior of the Gai-Mariagal clan.

- Pemulwuy, a warrior and resistance leader of the Bidjigal clan.

- Tunnerminnerwait, an Aboriginal resistance fighter from Tasmania.

- Windradyne, a warrior and resistance leader of the Wiradjuri nation.

- Australian frontier wars

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |