Edward Gibbon Wakefield facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Gibbon Wakefield

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of New Zealand Parliament for Hutt | |

| In office 1853–1855 |

|

| Succeeded by | Dillon Bell |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada for Beauharnois | |

| In office 1842–1843 |

|

| Preceded by | John William Dunscomb |

| Succeeded by | Eden Colvile |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 March 1796 London, Great Britain |

| Died | 16 May 1862 (aged 66) Wellington, New Zealand |

| Spouse |

Eliza Pattle

(m. 1816; died 1820) |

Edward Gibbon Wakefield (born March 20, 1796 – died May 16, 1862) was a very important person in setting up the colonies of South Australia and New Zealand. He later became a member of parliament in New Zealand. He was also involved in British North America (now Canada). He helped write a key report for Lord Durham and was a member of the Parliament of the Province of Canada for a short time.

Wakefield was famous for his plan to create new colonies. This plan, sometimes called the Wakefield scheme, aimed to bring together different kinds of people. He wanted to attract workers, skilled tradespeople, and wealthy investors to new colonies like South Australia. The idea was that selling land to the investors would help pay for other people to move there.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Edward Gibbon Wakefield was born in London in 1796. He was the oldest son of Edward Wakefield, who was a well-known surveyor and land agent. His grandmother, Priscilla Wakefield, was a popular writer for young people. She also helped start savings banks.

Edward had many brothers and sisters. Some of his brothers, like Arthur Wakefield and William Hayward Wakefield, later played important roles in New Zealand's history.

He went to school at Westminster School in London and also studied in Edinburgh.

Early Career and Family Life

After school, Wakefield worked as a King's Messenger. This meant he carried important diplomatic messages across Europe. He did this during the final years of the Napoleonic Wars, even after the big Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

In 1816, he married Eliza Pattle in Edinburgh. Eliza was a wealthy heiress. Edward received a large sum of money, about £70,000, as part of their marriage agreement.

The couple moved to Genoa, Italy, where Edward continued his diplomatic work. Their first child, Susan Priscilla Wakefield (called Nina), was born there in 1817. In 1820, they returned to London, and their second child, Edward Jerningham Wakefield, was born. Sadly, Eliza died four days later. Edward then left his job. His older sister, Catherine, helped raise his two children.

Nina became ill with tuberculosis. Edward took her to Lisbon, Portugal, hoping the climate would help her get better. He hired a young girl, Leocadia de Oliveira, to help care for Nina. After Nina's death in 1835, Edward sent Leocadia to Wellington, New Zealand. There, she married and had a large family.

Wakefield's Influence on British Colonization (1829–1843)

While in prison, Wakefield started thinking about how colonies were set up. He noticed that colonies like those in Australia grew slowly. This was because land was given away too easily, and there wasn't a good plan for bringing in new settlers. This meant there weren't enough workers.

Principles of "Systematic Colonization"

Wakefield suggested a new way to colonize. He proposed selling land in smaller amounts at a fair price. The money from these land sales would then be used to help more people move to the colony. He wrote about these ideas in a book called Letter from Sydney in 1829.

In 1830, the National Colonization Society was formed. This group supported Wakefield's ideas for "systematic colonisation". Their plan had three main points:

- Carefully choosing people who would move to the colony.

- Making sure settlers lived close together.

- Selling land at a set, fair price to fund new settlers.

Many important people joined this society, including John Stuart Mill. In 1831, the British government adopted some of Wakefield's ideas. They stopped giving away land for free and started selling it at a minimum price in the colony of New South Wales.

South Australia's Founding

Wakefield believed that many problems in Britain, like too many people, could be solved by moving to colonies. He wanted to create a colony with a good mix of workers, skilled people, and investors. The investors would buy land, and this money would help other settlers move there.

He was very involved in the early plans to create the British Province of South Australia. However, as the plan got closer to happening, he had less and less say. He eventually stepped away from the project.

Ideas for America

In 1833, Wakefield wrote another book, England and America. This book further explained his ideas about colonization. It also contained some new and interesting proposals, like making mail delivery completely free.

New Zealand Association

Soon, Wakefield got involved in a new project: the New Zealand Association. In 1837, this group received permission to promote settlement in New Zealand. However, the government added conditions that the Association found difficult to accept.

Working in Canada (First Time)

Around this time, Wakefield also became interested in Canada. There had been a rebellion in Lower Canada in 1837, and the colony was in chaos. The British government sent Lord Durham to fix the problems. Durham and Wakefield had worked together on the New Zealand plan, and Durham liked Wakefield's ideas.

Wakefield secretly sailed to Canada with his son in 1838. Even though the British government didn't officially approve his appointment, Lord Durham kept him as an unofficial advisor. Together, they helped calm the situation and brought about the union of Upper and Lower Canada. Lord Durham was often ill, so Wakefield and Charles Buller deserve a lot of credit for the mission's success.

After returning to Britain, Lord Durham wrote a report about his time in Canada. This report, which Wakefield likely helped write, became a guide for how Britain would manage its colonies in the future.

The New Zealand Company

The New Zealand Association later became the New Zealand Company in 1838. Wakefield became a director of the company. His belief was simple: "If you own the land, you are safe."

The company quickly bought a ship called the Tory. Wakefield urged them to sail to New Zealand as soon as possible. His brother William led the expedition, with his son Jerningham as his secretary. The Tory left England in May 1839 and reached New Zealand 96 days later.

Wakefield himself did not sail with the first settlers. He was better at planning big ideas and convincing others to join. He was a great salesman and politician. He secretly advised many parliamentary committees on colonial matters.

By the end of 1839, he had sent eight more ships to New Zealand. He also recruited another brother, Arthur, to lead an expedition to settle the Nelson area. Many of his family members, including nieces and nephews, eventually moved to New Zealand.

Working in Canada (Second Time)

Even while busy with the New Zealand Company, Wakefield kept an eye on Canadian affairs. He became involved with a group called the North American Colonial Association of Ireland (NACAI). He pushed for them to buy a large estate near Montreal to start another settlement.

The NACAI sent Wakefield back to Canada as their representative in 1842. Canada was still adjusting to the union of Upper and Lower Canada. There were big differences between the French and English Canadians. Wakefield cleverly used these differences to gain support. By the end of that year, he was elected to the Canadian Parliament. After being elected, he immediately returned to Britain.

He went back to Canada in 1843 for a few months. He initially supported the French-Canadian group in parliament. However, when he heard that his brother Arthur had died in the Wairau Affray in New Zealand, he left Canada for good. This was the end of his involvement with Canadian affairs.

Later Years in England and Illness (1844–1852)

Wakefield returned to England in early 1844. The New Zealand Company was facing serious problems from the Colonial Office. He worked hard to save his project. In August 1844, he had a stroke, and then several more smaller ones. He had to retire from active work. His son Jerningham returned from New Zealand and took care of him.

During his recovery, he wrote a book called A View of the Art of Colonization. It was written as letters between a "Statesman" and a "Colonist."

By 1846, Wakefield was back to planning. He suggested a radical idea to the new Colonial Secretary, Gladstone. He proposed that both the government and the New Zealand Company should step away from New Zealand affairs. Instead, the colony should govern itself.

In August 1846, he had another serious stroke. His friend, Charles Buller, took over the negotiations. In 1847, the British government agreed to take over the New Zealand Company's debts and buy out its interests in the colony. Wakefield was unhappy that he couldn't influence this decision.

Meanwhile, his youngest brother, Felix Wakefield, who had been in Tasmania, suddenly appeared in England with eight of his children. Felix had no money, so Edward helped him find a place to live and arranged for relatives to care for the children.

Wakefield also got involved in a new plan with John Robert Godley. They worked to create a new settlement in New Zealand, supported by the Church of England. This plan became the Canterbury Settlement. The first ship sailed from England in December 1849.

In the same year, Wakefield helped start the Colonial Reform Society. He continued to work for the Canterbury Association and pushed for New Zealand to become a self-governing colony. The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 was passed in June 1852, giving New Zealand more control over its own affairs.

Move to New Zealand (1853)

Wakefield decided he had done all he could in England. It was time to see the colony he had helped create. He sailed from Plymouth in September 1852, knowing he would not return. His sister Catherine and his father came to see him off. He and his father, who was 78, had not spoken for 26 years, but they made up before he left.

His ship arrived at Port Lyttelton on February 2, 1853. Wakefield had traveled with Henry Sewell, who was a manager for the Canterbury Association. Wakefield likely expected a big welcome as a founder of the colony. However, many settlers in Canterbury felt let down by the Association's broken promises. They linked Wakefield and Sewell to these disappointments.

James Edward FitzGerald, a leader in Canterbury, was elected Superintendent a few months later. He was not eager to meet Wakefield or give up control to someone he saw as a politician from London.

Wakefield quickly became unhappy with Canterbury. He felt the people were too focused on local issues rather than national politics. After only one month, he left Canterbury and sailed for Wellington.

Wellington had more political excitement, which suited Wakefield. Governor George Grey had just announced self-government for New Zealand. However, it was a weaker version than what was described in the New Zealand Constitution Act. Grey was a strong leader with his own ideas for New Zealand, which were different from Wakefield's. It seemed clear that the two men would clash.

When they arrived in Wellington, Wakefield waited on the ship until he knew he would be properly welcomed by the Governor. Governor Grey, however, left town. Sewell went ashore and met with important people, including Wakefield's brother, Daniel Bell Wakefield, who was the Attorney General. Sewell also managed to get a welcome address for Wakefield, signed by many citizens.

Wakefield immediately began to challenge Governor Grey. He disagreed with Grey's policy of selling land very cheaply to attract settlers. Wakefield believed land should be sold at a high price to fund the colony's growth. This was a key part of his colonization theory. Wakefield and Sewell tried to stop the Commissioner of Crown Lands from selling more land under Grey's rules. The Commissioner was Wakefield's second cousin, Francis Dillon Bell, showing how much the Wakefield family was involved in early New Zealand.

Within a month of arriving in Wellington, Wakefield started a campaign in London to have Governor Grey removed. Meanwhile, Grey fought back by questioning Wakefield's honesty. He highlighted the large fees Wakefield had received as a director of the New Zealand Company, especially when the company was not paying its debts in New Zealand. This reminded the people of Wellington how angry they felt about the company. Wakefield managed to clear himself of the specific charges, but a lot of accusations were made.

Member of Parliament

| New Zealand Parliament | ||||

| Years | Term | Electorate | Party | |

| 1853–1855 | 1st | Hutt | Independent | |

Elections for the Wellington Provincial Council and the General Assembly (the national parliament) were held in August 1853. Wakefield ran for the Hutt electorate. To the surprise of some, he was elected to both the Provincial Council and the General Assembly.

The Provincial Assembly first met in October 1853. Wakefield was the most senior and politically experienced member. However, the Assembly was controlled by the Constitutional Party, led by Dr. Isaac Featherston. This party had recently criticized Wakefield. Working in opposition, Wakefield helped ensure the Provincial Assembly became a true democracy. His deep knowledge of parliamentary rules meant that the ruling party could not ignore the other members.

In early 1854, Wellington held a Founders' Festival. Three hundred people attended, including sixty Māori and all the Wakefields. The main toast of the evening was to "The original founders of the Colony and Mr. Edward Gibbon Wakefield." This showed that Wakefield was seen as one of the colony's leading political figures, perhaps the only one strong enough to challenge Governor Grey.

Conflict Over Responsible Government

Governor Grey had left, and Colonel Robert Wynyard was acting as Governor. Wynyard opened the 1st New Zealand Parliament on May 27, 1854. Wakefield and James FitzGerald immediately began trying to gain influence. Wakefield proposed that Parliament should appoint its own responsible governments (Ministers of the Crown). Wakefield supported Wynyard, while FitzGerald took the opposite side. The argument over responsible government continued for some time.

As a compromise, Wynyard appointed James FitzGerald to the Executive Council on June 7. Wakefield was not asked to join the ministry.

By July 1854, FitzGerald was in serious disagreement with Wynyard. FitzGerald's Executive Council resigned on August 2, 1854. Wakefield was asked to form a government, but he refused. Instead, he said he would advise Wynyard, but only if Wynyard followed his advice alone. He wanted to control Wynyard. However, Wakefield did not have enough support in the house, and the assembly became stuck. Wynyard temporarily closed parliament on August 17. He had to reopen it by the end of the month because he needed money to run the country. The new ministry, led by Thomas Forsaith, was mostly made up of Wakefield's supporters. It quickly became clear that Wakefield was the real leader of this ministry. However, they lost an early vote of no confidence, and New Zealand's second government fell on September 2, 1854. In the remaining two weeks, they passed some useful laws before new elections were called.

Wakefield held two successful election meetings for his voters in the Hutt Valley. A third meeting was planned but never happened. On the night of December 5, 1855, Wakefield became ill with rheumatic fever and neuralgia (nerve pain). He retired to his house in Wellington. He left his seat in the Hutt on September 15, 1855, and stopped all political activity. He lived for another seven years, but his time in politics was over.

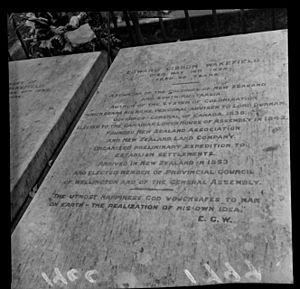

Death and Legacy

Wakefield's niece, Alice Mary Wakefield, had cared for him since his stroke in 1846. She continued to look after him until he died in Wellington in 1862.

In 1839, John Hill named the Wakefield River, north of Adelaide in South Australia, after Edward Gibbon Wakefield. This later led to the naming of Port Wakefield. Wakefield Street, Adelaide, was also named after him.

In 2020, some local council members in Wellington suggested removing monuments dedicated to Wakefield.

Selected Publications

- Facts Relating to the Punishment of Death in the Metropolis by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, 1831.

- A View of the Art of Colonization by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, 1849.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |